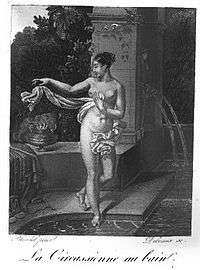

La Circassienne au Bain

La Circassienne au Bain, also known as Une Baigneuse, was a large Neoclassical oil painting from 1814 by Merry-Joseph Blondel depicting a life-sized young Circassian woman bathing in an idealized setting from classical antiquity. The painting was destroyed with the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. When financial compensation claims were filed with US commissioner Gilchrist in January 1913, the painting gained notoriety as the subject of the largest claim made against the White Star Line for the loss of a single item of baggage or cargo.[1]

History

Louvre Exhibition

The painting was first exhibited at the Paris Salon, at the Louvre museum in November 1814.[2] The initial critical reaction to the painting was muted, with positive descriptions restricted to praising the painting's overall competence and Blondel's attention to detail.[3] Apart from technical misgivings about the twist of the upper body and the absence of 'grace' in the figure of the young woman, the chief concern of the critics seems to have been that, despite its large scale, it was not as exciting a painting as some of Blondel’s previous works.[4] However, by 1823, critics began talking more enthusiastically about the painting, apparently influenced both by the favourable popular reception to printed reproductions of the painting and by Blondel’s improving career status.[5]

Loss on the RMS Titanic

In January 1913, a claim was filed in New York against the White Star Line, by Titanic survivor Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, for financial compensation resulting from the loss of the painting. The amount of the claim was $100,000 ($2.4 million equivalent in 2014), making it by far the most highly valued single item of luggage or cargo lost as a result of the sinking.[6]

Size of the painting

Steffansson's claim form described a substantial painting "8 x 4 feet" in size, but did not specify whether this referred to the painted canvas size, the canvas plus frame or the crate size.[7] This format does not conform to the standard size conventions for full length portraits, formalised during the 19th century. Neither does it match the format ratio of any known full length portrait by Blondel. Extant full length, life-sized standing female portraits by Blondel, in the public domain, conform to the French standard F120 (figure 120) sized canvas (195cm (76.75inches) x 130cm (51.25 inches)), within a margin of plus or minus 10cm (4 inches).

References

- ↑ The New York Times, Thursday January 16th, 1913, Titanic Survivors Asking $6,000,000, p.28

- ↑ Livret du Salon du Louvre Explication des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, Architecture et Gravure exposes au musee royal des arts, le 1er Novembre 1814, p.11

- ↑ Le Spectateur, No. xxv: Observations sur l’etat des arts au dix-neuvieme siecle, dans le salon de 1814. p.246

- ↑ Delpech, M. S. Examen raisonne des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture et gravure, exposes au salon du Louvre en 1814, p. 174

- ↑ Cotta F.G. Almanach des Dames pour l’An 1823, Paris, Gravure No. 2, pp5-8

- ↑ The New York Times, Thursday January 16th, 1913, Titanic Survivors Asking $6,000,000, p.28

- ↑ District Court of the United States, Southern district of New York, Claim by H. Bjornstrom-Steffanson - Exhibit A, 9th January 1913, US National Archives, New York.

External links

Media related to La Circassienne au Bain at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to La Circassienne au Bain at Wikimedia Commons