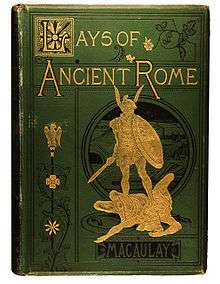

Lays of Ancient Rome

Lays of Ancient Rome is a collection of narrative poems, or lays, by Thomas Babington Macaulay. Four of these recount heroic episodes from early Roman history with strong dramatic and tragic themes, giving the collection its name. Macaulay also included two poems inspired by recent history: Ivry (1824) and The Armada (1832).

Overview

The Lays were composed by Macaulay in his thirties, during his spare time while he was the "legal member" of the Governor-General of India's Supreme Council from 1834 to 1838. He later wrote of them:

The plan occurred to me in the jungle at the foot of the Neilgherry hills; and most of the verses were made during a dreary sojourn at Ootacamund and a disagreeable voyage in the Bay of Bengal.[1]

The Roman ballads are preceded by brief introductions, discussing the legends from a scholarly perspective. Macaulay explains that his intention was to write poems resembling those that might have been sung in ancient times.

The Lays were first published by Longman in 1842, at the beginning of the Victorian Era. They became immensely popular, and were a regular subject of recitation, then a common pastime. The Lays were standard reading in British public schools for more than a century. Winston Churchill memorised them while at Harrow School, in order to show that he was capable of mental prodigies, notwithstanding his lacklustre academic performance.[2]

The poems

Horatius

The first poem, Horatius, describes how Publius Horatius and two companions, Spurius Lartius and Titus Herminius, held the Sublician bridge against the Etruscan army of Lars Porsena, King of Clusium. The three heroes are willing to die in order to prevent the enemy from crossing the bridge, and sacking an otherwise ill-defended Rome. While the trio close with the front ranks of the Etruscans, the Romans hurriedly work to demolish the bridge, leaving their enemies on the wrong side of the swollen Tiber.[3]

This poem contains the often-quoted lines:

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods."[1]

- ^ Longman edition. p. 56.

Lartius and Herminius regain the Roman side before the bridge falls, but Horatius is stranded, and jumps into the river still wearing his full armor. Macaulay writes,

And when above the surges

They saw his crest appear,

All Rome sent forth a rapturous cry,

And even the ranks of Tuscany

Could scarce forbear to cheer.

He reaches the Roman shore, is rewarded, and his act of bravery earns him mythic status:

With weeping and with laughter

Still is the story told,

How well Horatius kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.

The Battle of Lake Regillus

This poem celebrates the Roman victory over the Latin League, at the Battle of Lake Regillus. Several years after the retreat of Porsena, Rome was threatened by a Latin army led by the deposed Roman king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, together with his son, Titus Tarquinius, and his son-in-law, Octavius Mamilius, prince of Tusculum. The fighting described by Macaulay is fierce and bloody, and the outcome is only decided when the twin gods Castor and Pollux descend to the battlefield on the side of Rome.

This poem includes a number of finely described single-combats, in conscious imitation of Homer's Iliad.[4]

Virginia

This poem describes the tragedy of Virginia, the only daughter of Virginius, a poor Roman farmer. The wicked Appius Claudius, a member of one of Rome's most noble patrician families, and head of the college of decemvirs, desires the beautiful and virtuous Virginia. He initiates legal proceedings, claiming Virginia as his "runaway slave", knowing that his claim will be endorsed by the corrupt magistracy over which he and his cronies preside. Driven to despair, Virginius resolves to save his daughter from Claudius' lust by any means—even her death is preferable.

Virginia's sacrifice stirs the plebeians to action: their violent outbursts lead to the overthrow of the decemvirs, and the establishment of the office of tribune of the plebs, to protect the plebeian interest from abuses by the established patrician aristocracy.[5]

The Prophecy of Capys

When Romulus and Remus arrive in triumph at the house of their grandfather, Capys, the blind old man enters a prophetic trance. He foretells the future greatness of Romulus' descendants, and their ultimate victory over their enemies in the Pyhrric and Punic wars.[6]

Ivry, A Song of the Huguenots

Originally composed in 1824, Ivry celebrates a battle won by Henry IV of France and his Huguenot forces over the Catholic League in 1590. Henry's succession to the French throne was contested by those who would not accept a Protestant king of France; his victory at Ivry against superior forces left him the only credible claimant for the crown, although he was unable to overcome all opposition until converting to Catholicism in 1593. Henry went on to issue the Edict of Nantes in 1598, granting tolerance to the French Protestants, and ending the French Wars of Religion.

The Armada: A Fragment

Written in 1832, this poem describes the arrival at Plymouth in 1588 of news of the sighting of the Spanish Armada, and the lighting of beacons to send the news to London and across England,

Till Skiddaw saw the fire that burnt on Gaunt's embattled pile,

And the red glare on Skiddaw roused the burghers of Carlisle.

The Armada was sent by Philip II of Spain with the goal of conveying an army of invasion to England, and deposing the Protestant Queen Elizabeth. The supposedly invincible fleet was thwarted by a combination of vigilance, tactics taking advantage of the size and lack of maneuverability of the Armada and its ships, and a series of other misfortunes.

In popular culture

Lays of Ancient Rome has been reprinted on numerous occasions, and is now in the public domain. An 1881 edition, lavishly illustrated by John Reinhard Weguelin, was frequently republished. Countless schoolchildren have encountered the work as a means of introducing them to history, poetry, and the moral values of courage, self-sacrifice, and patriotism emphasized in Macaulay's text.

The phrase "how can man die better", from Horatius, was used by Benjamin Pogrund as the title of his biography of anti-apartheid activist Robert Sobukwe. The same portion of the poem was recited in an episode of Doctor Who,[7] used as a plot device in the 2013 science fiction film Oblivion,[8] and appears in the final book of Kevin J Anderson's The Saga of Seven Suns.[9] Verses 32 and 50 of Horatius are used as epigraphs in Diane Duane's Star Trek novels, My Enemy, My Ally and The Empty Chair.[10]

These words are on the epitaph at the Chushul war memorial at Rezang La in memory of the 13th Battalion, Kumaon Regiment of the Indian Army.

References

- ↑ Peter Clarke (October 1967). A Macaulay Letter. Notes and Queries, p. 369.

- ↑ Winston Churchill, My Early Life, chapter 2.

- ↑ Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1847) The Lays of Ancient Rome, pp. 37ff, London: Longman

- ↑ Longman edition pp. 95ff.

- ↑ Longman edition pp. 143ff.

- ↑ Longman edition pp. 177ff.

- ↑ Doctor Who, "The Impossible Planet" (2006).

- ↑ Richard Corliss (19 April 2013). "Tom Cruise in Oblivion: Drones and Clones on Planet Earth". Time. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Saga of Seven Suns, "The Ashes of Worlds".

- ↑ Diane Duane, My Enemy, My Ally, Pocket Books, 1984; ISBN 0671502859; The Empty Chair, Pocket Books, 2006; ISBN 9781416531081.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- full text at archive.org

- full text at Poets' Corner

- full text (with illustrations by George Scharf) at hathitrust.org

-

The Lays of Ancient Rome public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Lays of Ancient Rome public domain audiobook at LibriVox - German edition (in English) digitized by Google Books