Leroy Griffith

| Leroy Griffith | |

|---|---|

Griffith with Sammy Davis, Jr. (circa 1966). | |

| Born |

Leroy Charles Griffith March 26, 1932 Poplar Bluff, Missouri, U.S. |

| Residence | Miami, Florida |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1949–present |

| Known for | Stage shows (Hello Burlesque, This Was Burlesque, etc.); chief executive officer of Club Madonna |

| Home town | Poplar Bluff, Missouri |

| Spouse(s) | Linda Rivera (1989–present) |

| Children | 3 sons, 1 daughter |

| Website | clubmadonna.com |

Leroy Charles Griffith (born March 26, 1932) is an American theater and nightclub proprietor, former Broadway theater producer, and film producer. He has owned, leased, or operated more than 60 adult entertainment theaters across the United States, dating from the burlesque era of the 1950s to present day nightclubs.[1] During burlesque's heyday, he was a prolific producer of live stage shows featuring showgirls, strippers, comedians, and other stars of the era.

His business endeavors in the adult entertainment industry have, for decades, put him at odds with restrictive municipalities, and he has taken legal action, often successfully, to be able to operate his establishments.

Early life

Griffith was born in Poplar Bluff, Missouri to Floyd R. and Stella Griffith. His father was a theater owner. The younger Griffith began as a projectionist, cashier, and usher at a local theater in his hometown. At 17, he left for St. Louis and a job working concessions for Oscar Markovich at the Grand Burlesque Theater. At the Grand, Griffith started as a "candy butcher," hawking candy and trinkets to audiences before and during intermission.[2] "In those days," he said in a 1993 interview, "they had probably 30 people in the cast, a chorus line, an orchestra, two comics, a singer, a vaudeville act, and then five exotic dancers. It was a good show."[3]

Griffith discovered that any profit to be made was not from the show itself but from the concession stand: "That's where I was. In between acts, the pitchman would sell prize packages, candy, stuff like that. Concessions was where the real money was, just like it is with regular movies today."[3] After working his way up to concession manager, Griffith began saving money, his eye set on greater aspirations.

Military service

In 1955, Griffith was drafted into the armed services. While stationed at Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage, Alaska, he worked with Bob Hope's USO show (featuring Jerry Colonna, Mickey Mantle, and Ginger Rogers, among others) when Hope was on tour there in December 1956.

After an early discharge, Griffith acquired his first theater, the Star, in Portland, Ore. After a limited operation of a Kansas City, Mo., restaurant and another period of short-term employment with Markovich, he opened a theater in Detroit. He was in his mid-twenties.

Career

Theater and club owner

Identifying "legitimate" theaters that were going out of business, Griffith began acquiring them. "These places would go under," he said in a 1993 interview, "and I'd go in and take over and make them successful with an adult policy."[3] He soon acquired theaters throughout the United States.

South Florida (1961- )

On a visit to Miami Beach in 1961, Griffith noticed the Paris Theater at 550 Washington Avenue was for sale. He leased it, then bought it, originally staging burlesque, including featuring Tempest Storm. But back in the early '60s, Griffith didn't call it "burlesque"; doing so would have been against local law. "You couldn't even use the word," he recalled in a 1993 interview. "I had one big stage show called 'The Top Stars of Burlesque,' with Blaze Starr and all these people. I told the city, 'It's not burlesque. It's the top stars of burlesque. There's no law against the people of burlesque.' The city decided they'd fix me by charging me $1,000 for a special license to do the show. I said fine. I was going to have to pay $1,600 for a regular permit anyway."[3]

Griffith continued to open new venues throughout South Florida, from Broward County in the north to Key West in the south. In addition to bringing in live acts, he began showing movies. He also began producing films and exhibiting them in his theaters.

A young Mickey Rourke once worked for Griffith as a cashier and projectionist at one of his Miami Beach theaters.[3]

Film producer

Griffith produced Bell, Bare and Beautiful (1963), Lullaby of Bareland (1964), Mundo depravados (1967), and My Third Wife, George (1968).[5]

Film appearances

Griffith played brief cameo parts in some of his films. His recollections of the burlesque era are featured in Leslie Zemeckis's 2010 documentary, Behind the Burly Q.[6]

Broadway producer

This Was Burlesque, a revue conceived by and starring burlesque star Ann Corio, was staged at Griffith's Hudson Theater on Broadway during the 1964-65 season. It went on to tour across the U.S. in various forms over the next two decades.[7]

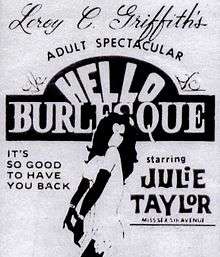

Griffith also produced Hello Burlesque, a live stage show featuring showgirl Julie Taylor, "Miss Sex 5th Avenue."

Griffith's theaters and clubs

Theaters he has owned and operated, been an ownership partner in, leased, and/or managed include these:

Note: Click the "sort" icon at the head of each column to view data in alphabetical or numerical order.

| State | City | Name of theater | Other names | Summary | Opened | Closed | Demolished | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maryland | Baltimore | Paris | ||||||

| Illinois | Chicago | Follies | Gem; London Dime Museum | Located at 450 S. State Street.[8][9] | 1890s | 1978, following fire | 434 | |

| Illinois | Chicago | Minsky's Rialto | Downtown; Loop End | Formerly located at 336 S. State Street, two blocks from the Gayety. Opened as a venue for vaudeville and movies, it was a burlesque house by the 1930s and closed in 1953. It is the site today of Pritzker Park.[10][11] | 1917 | 1953 | 1954 | 1,548 |

| Indiana | Fort Wayne | Little | Capitol; Little Cinema | Formerly at Berry Street and Harrison Street.[12] | yes | yes | 435 | |

| Indiana | Indianapolis | Ritz | Middle Earth; Northside | Located at 3422 N. Illinois Street. Considered one of the leading movie houses in the city. Burlesque took over in 1962. Known as the Northside from 1958 to 1970. Remodeled, it became a rock concert venue and resumed its former name, but closed in 1972.[13][14] | 1927 | 1972 | 1,400 | |

| Missouri | Kansas City | Folly | Century; Folly Burlesque; Shubert's Missouri; Standard | Located at 300 W. 12th Street.[15][16] Following a renovation in the 1980s, it remains in use today. Was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. in 1973 |

1900 | open | 1,078 | |

| Missouri | Kansas City | Strand | Located at 3544 Troost Avenue. Oldest still-operating theater in Kansas City. Began showing adult movies in the '70s.[17][18] | 1917 | open | 268 (650 in 1950) | ||

| Michigan | Detroit | Garden | Peek-A-Rama; Sassy Cat; Woodward | Located at 3929 Woodward Avenue. A century after its opening, it was undergoing an estimated $14 million makeover to become the 1,300-seat Woodward Theater.[19][20][21] | 1912 | reopened | 903 | |

| Michigan | Detroit | National | Gayety; Palace | Located at 118 Monroe Street. Has fallen into disrepair.[22][23]

|

1911 | 1975 | 2,200 | |

| Michigan | Flint | Michigan | Located at 1614 S. Saginaw Street.[24][25] | 1929 | 1965 or 1975 | 1,500 | ||

| New York | Syracuse | Civic | Adam and Eve; Civic Follies; Ritz; Syracuse; System; Top | Formerly located at 527 S. Salina Street.[26][27] | yes | 1,500 | ||

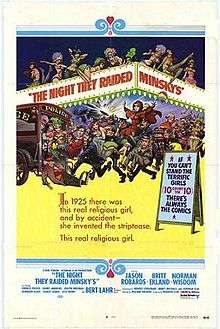

| New York | New York City | Gayety | 12th Street Cinemas; Casino East; Century; Eden; Entermedia; Louis N. Jaffe Art; Molly Picon; Phoenix; Second Avenue; Stuyvesant; Yiddish Art | Located at 181 Second Avenue, in Manhattan. Theater sequences for the 1968 film The Night They Raided Minsky's were shot here.[28]

|

1926 | |||

| New York | New York City | Hudson | Avon-on-the-Hudson; Savoy | Located at 141 W. 44th Street in midtown Manhattan. A former Broadway theater, now a conference center and special event venue. In 1954 it became home to the original version of The Tonight Show with host Steve Allen.[29][30] in 2003 |

1903 | 1,100 | ||

| New York | New York City | Mayfair Burlesque | Billy Rose's Diamond Horseshoe | Located at 235 West 46th Street. It was a theater in the basement of the Paramount Hotel. From 1938 to 1951, theatrical impresario and song writer Billy Rose operated his Diamond Horseshoe nightclub there. | 400 | |||

| New York | New York City | Metropolitan | 14th Street; Arrow; "The Met" | Formerly located at 241 East 14th Street.[31][32] | 1914 | 1988 | yes | 600 |

| New York | New York City | Shore | Loew's Coney Island | Located at 1301 Surf Avenue in Brooklyn, across from Coney Island.[33][34] |

1925 | 1973 | 2,472 | |

| New Jersey | Newark | Luxor | Luxor Follies | Formerly located at 264 Market Street.[35][36] | yes | 590 | ||

| New Jersey | Newark | Treat | Cameo Twin Cinema XXX | Located at 68 Orange Street.[37][38] | 2010 | 750 | ||

| Ohio | Cincinnati | Gayety | Empress; Gayety Burlesk | A Vine Street theater that opened as the Empress and became the Gayety in 1922. Its demolition made way for a main library.[39][40] | 1909 | 1970 | 1970 | |

| Ohio | Cincinnati | Imperial | Imperial Follies | Located at 282 McMicken Avenue. Presented adult films and later, in the '60s, live burlesque shows.[41][42] | yes | 771 | ||

| Ohio | Cleveland | University | Circus Maximus; PAT (Performing Arts Theater); Scrump-Dee-Dump-Dee | Formerly located at 10606 Euclid Avenue.[43][44] | 1920s | 1982 | yes | 900 |

| Ohio | Columbus | Little Art | Olentangy; Piccadilly; World | Located at 2523 N. High Street, it opened in the silent picture era as The Piccadilly. An adult movie theater from the '50s to its demolition.[45][46] | 1976 | 417 | ||

| Ohio | Columbus | Livingston | Gayety | Located at 1567 East Livingston Avenue. As of late 2012, there were plans to renovate it.[47] | 1946 | 1970s | 1,000 | |

| Ohio | Columbus | Parsons | Parson Follies | Located at 1293 S. Parsons Avenue.[48][49] | 830 | |||

| Ohio | Steubenville | Ohio | Located on Market Street.[50] | 800 | ||||

| Ohio | Toledo | Gayety | Gayety Burlesk; Guild; Hollywood Burlesk; Strand | Located at 322 N. Summit Street.[51][52] | 1920 | yes | 390 | |

| Ohio | Toledo | Town Hall | Formerly located at Orange and St. Clair Streets.[53] | c. 1887 | 1968 | |||

| Ohio | Youngstown | Strand | Formerly located in Central Square. Closed as a movie house in the 1950s, then reopened featuring live burlesque and adult movies.[54][55] | 1916 | yes | 750 | ||

| Ohio | Geneva-on-the-Lake, Ohio | State | Lyceum | |||||

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia | Aardvark | Cayuga | Formerly located at 4371 Germantown Avenue. Opened as the Cayuga.[56][57][58] | 1911 or 1915 | 1955 | yes | 460 |

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia | Howard | Howard Follies | Located at 2614 N. Front Street. In the early '60s, it operated with an adults-only policy and advertised as the Howard Follies.[59][60] | 1925 | yes | 900 | |

| Pennsylvania | Pittsburgh | Cameraphone | Located at 6202 Penn Avenue.[61][62] | 1908 | c. 1967 | yes | 776 | |

| Wisconsin | Superior | Tower | Located on Tower Ave. | |||||

| Oregon | Portland | Capitol | Blue Mouse | Located at 626 SW 4th Street. Renamed the Blue Mouse in 1958. Famous stripper Tempest Storm co-owned and operated the Capitol in the 1950s.[63][64][65][66] | 1928 | 1977 | 850 | |

| Oregon | Portland | Star | Princess; Star Burlesk | Located at 13 NW 6th Avenue. Opened as the Princess, screening silent movies. Became the Star Burlesk in 1939, presenting burlesque shows. Refurbished, it remains in operation today.[67][68]

|

1911 | open | 300 | |

| Florida | Jacksonville | Little | Harold K. Smith Playhouse | Located at 2032 San Marco Boulevard.[69][70] Its landlord, Griffith said in a 1993 interview, "was the county sheriff" at the time. | 1920 | open | ||

| Florida | Orlando | Luv | Located at 355 N. Orange Avenue. | |||||

| Florida | Warrington | Navy Point | Formerly located on Sunset Avenue. Opened after World War II for the entertainment of military families stationed in the Pensacola area.[71][72] | 1946 | yes | 750 | ||

| Florida | Tampa | Ritz | Masquerade; Rivoli | Located at 1503 E. 7th Avenue in Tampa's Ybor City section. Opened as the Rivoli; expanded in the 1930s as the Ritz and showed movies until 1982. Reopened in 2008 and is used for concerts and special events.[73][74]  |

1917 | open | 1,004 | |

| Florida | Tampa | Casino | Casino Follies | Located at 1536 7th Avenue in Tampa's Ybor City section. Closed in the 1970s, then was renovated and reopened c. 2000. It is home today to the Tampa Improv Comedy Club.[75][76] | 1912 | open | 700 | |

| Louisiana | New Orleans | Carrollton | Located at 4710 S. Carrollton Avenue. A classic Art Deco-style theater, it suffered water damage during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 but has since been refurbished as a banquet hall.[77][78] | 1935 | yes | 750 | ||

| Louisiana | New Orleans | Cine Royale | Center; Wonderland | Located at 912 Canal Street. It became an adult theater after 1975.[79][80] | 1997 | 600 | ||

| Louisiana | New Orleans | Sinerama | Cinerama Adult; Martin Cinerama; Mike Todd's Cinerama; Pussycat; Trans-Lux Cinerama | Formerly located at 3615 Tulane Avenue. Under Griffith's management, it was known as the Pussycat and Sinerama.[81][82] | 1962 | 1984 | 2001 | 900 |

| North Carolina | Charlotte | Astor | Neighborhood | Located at 511 E. 36th Street. Called "The Carolina’s Most Unusual Theater" in newspaper ads in the '60s, it was restored in recent years and today (as the Neighborhood) features bands and musicians.[83][84] | 1945 | open | 446 | |

| North Carolina | Climax I and II | |||||||

| Tennessee | Chattanooga | Capitol | Formerly located at 528 Market Street.[85][86] | 1940 | yes | 622 | ||

| Washington, D.C. | Central | Gayety; Imperial; Moore's Garden Theatre | Formerly located at 425-433 9th Street NW.[87][88] Opened as the The Imperial. Renamed Moore’s Garden Theatre in 1913. Renamed the The Central in 1922. Renamed by Griffith as the Gayety Burlesque; presented live burlesque from the 1950s to its closing in the 1970s. | 1911 | 1973 | 851 | ||

| Florida | Fort Lauderdale | Adam and Eve | ||||||

| Florida | Hialeah | Atlas Twin | Formerly located at 1446 W. 49th Street.[89] | 1969 | 1993 | 400 | ||

| Florida | Miami | Boulevard | Black Gold; Club Madonna II; Kitty Cat; Pussycat; Pussycat II; Shadows; Tomcat; Wonderland | Located at 7770 Biscayne Boulevard. Has variously served as a strip club, night club, and adult theater.[90][91] Bought by Griffith for $165,000 in 1970 and renamed the Pussycat, he created three different theaters within: the Pussycat, the center theater, was a 900-seat theater that showed adult films including Deep Throat; the Kitty Cat featured female performers; and the Tomcat featured male performers.

|

1940 | open as a nightclub | 974 | |

| Florida | Miami Beach | Cameo | Located at 1445 Washington Avenue.[92][93] It is a nightclub today. |

1936 | open as a nightclub | 1,061 | ||

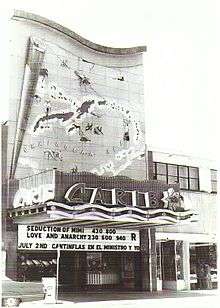

| Florida | Miami Beach | Carib | Located at 230 Lincoln Road.[94][95] "I used to do [benefit] shows at the Carib, which seated over 2,000 people," Griffith said in a 1993 interview, "and donated the theater, staff, advertising, and helped get talent. This all went to the widows and orphans of the firemen and the policemen."[3]

c.1976 |

1950 | 1975 | 2,200 | ||

| Florida | Miami | Dixie | Rio | Located at 222 NE First Avenue in downtown Miami. Renamed the Rio in 1965.[96][97] | 1948 | 1980 | 1,000 | |

| Florida | Miami Beach | Flamingo | Located at 320 Lincoln Road.[98][99] Converted into a present-day nightclub. | 1947 | 1980 | |||

| Florida | Miami Beach | Gayety Burlesque | Deja Vu; SoBe Showgirls | Formerly located at 2004 Collins Avenue. | yes | |||

| Florida | Key West | Monroe | Formerly located at 623 Duval Street.[100][101] | 1912 | 1995, following fire | 450 | ||

| Florida | Miami | Paramount | Fairfax | Formerly located at 257 East Flagler Street in downtown Miami.[102][103] | 1922 | yes | 2,200 | |

| Florida | Miami Beach | Paris | Paris Follies; Paris Moderne; Variety | Located at 550 Washington Avenue.[104][105] Griffith's first acquisition upon settling in the area in 1961. He originally leased it, then bought it, and staged burlesque there, under the name Paris Follies. Featured acts included Tempest Storm. He sold it in 1986, then bought it back after its owners failed with the nightclub Paris Moderne, and later sold it again.[3] | 1946 | open as a nightclub | 1,108 | |

| Florida | Hollywood | Pussycat | ||||||

| Florida | Miami | Rex Art | King Art Cinema; Rosetta; Second Ave. Art | Located at 7929 NE Second Avenue. First opened as the Rosetta.[106][107] | 1926 | yes | 981 | |

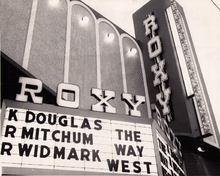

| Florida | Miami Beach | Roxy | Club Madonna | Located at 1527 Washington Avenue.[108][109] Griffith generated publicity there when, in 1967, he publicly invited city officials to a screening of the film, Man and Wife. "It was advertised as the art of making love 49 different ways," he said in a 1993 interview. "I don't remember inviting them, but I vaguely remember the incident. I think that was the first hard-core movie ever shown down here."[3] According to press accounts at the time, the officials seemed to think the movie was boring, but not obscene.[3] Griffith converted the Roxy from an adult movie theater to an all-nude strip club (Club Madonna), which it remains today. Griffith successfully withstood an attempt by attorneys for the pop singer Madonna to prevent him from using the name.[110] in 1967 |

open as a nightclub | |||

| Florida | Miami Beach | 21st Street | Fine Arts | Formerly located at 2039 Collins Avenue, at the corner of 21st Street.[111][112] | 1963 | |||

| Florida | Miami | Town | Formerly located at 265 East Flagler Street.[113][114] | yes | 472 | |||

| Florida | Miami | 79th Street Twin II Cinema | 79th St. Art; Bard; Little River | Formerly located at 137 NE 79th Street.[115][116] | yes | |||

| Washington | Seattle | Rivoli | Old Seattle; Tivoli | Formerly located at First Avenue and Madison Street. Opened as a burlesque theater featuring, among others, Sophie Tucker and Belle Baker. It later presented legit stage theater, then adult movies before its demolition.[117] | 1913 | 1970 | 900 | |

Controversies

vs. The City of Hialeah, Fla.

Griffith turned Hialeah's Atlas Cinema into an X-rated theater in August 1985, outraging Mayor Raul Martinez. "The issue is not censorship," Martinez said at the time. "It is morality. They will bring in derelicts, the sick of mind. They're like herpes -- wherever they go, everybody gets infected. We don't need that."[3]

The day after opening, in a pre-emptive strike, Griffith's lawyers sued the city, charging that a Hialeah zoning ordinance banning porn cinemas within 500 feet of residences was unconstitutional. His court challenge failed and the theater was ordered shut down.[3]

"I couldn't even use the word burlesque." [110]

— Griffith, recalling local regulations in '60s-era Miami Beach

vs. The City of Miami

In 1987, city officials confiscated movie projectors, a refreshment stand, and other property from Griffith's Pussycat Theater. He had just won a court fight with the city over his right to exhibit a film called Three Ripening Cherries. He was accused of owing more than $50,000 in fines dating back to 1978. The city bungled part of the collection process in a technical snafu, so Griffith ended up accountable for only $21,400.[3]

An auction of his theater equipment was conducted to satisfy that debt. The winning bid came in at $13,500, from Griffith himself, effectively reducing his penalties by another $8,000.[3]

vs. Miami-Dade County

Between 1976 and 1987, the Pussycat was raided 18 times. Efforts by the county to charge him with a felony for screening two obscene movies within 5 years collapsed when Griffith's attorney pointed out that too much time had elapsed between incidents. When prosecutors then indicated they might like to charge him with a simple misdemeanor for the more recent indiscretion (showing the film American Babylon), his attorney argued it had been two years since that film had been confiscated, thus denying Griffith his right to a speedy trial. The judge agreed and threw out the case.[3]

"If I was a judge taking bribes, a banker trying to swindle my customers out of bank funds, a doctor selling drugs, I might feel bad. But seeing a nude girl? There's nothing immoral about that. And there are more judges and lawyers and cops and bankers in jail than theater owners. I'm not hurting anyone, or stealing, or anything like that." [3]

— Griffith, in a 1993 interview

In April 1987, the Miami-Dade State Attorney's Office filed a ten-page complaint demanding that the Pussycat be shut down. This time the charge was brought under the Florida Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act. Because the Pussycat had been raided 18 times in eleven years, prosecutors contended, it must be an ongoing criminal enterprise. "That's not what the RICO Act was put in for," Griffith retorted. A judge agreed and dismissed the complaint.[3]

vs. The City of Miami Beach

In late 1989, after the cities of Fort Lauderdale and North Miami Beach outlawed alcohol in establishments featuring nude entertainers, Miami Beach officials—led by Mayor Alex Daoud—feared strip club operators would gravitate to their city and that Miami Beach "would be overrun with sex-mad drunken men and immoral, naked women."[3]

The imminent debut of the Gold Club, whose owners had intended to introduce nudity and alcohol in their new building on 5th Street, spurred the City Commission to pass local legislation prohibiting such a mix.[3]

Griffith announced that if the Gold Club was allowed to open with liquor and nudity, he would move his hard-core films from the Gayety Theater (then known as Deja Vu) to the Roxy, which then was showing second-run movies for general audiences. In turn, he would convert the Gayety into an upscale nude bar to compete with the Gold Club.

Daoud said, "We don't have to sit idly by and watch [adult clubs] open up. It would be detrimental to the growth of our city that has been developing so nicely."[3]

The city passed an ordinance in January 1990 prohibiting not only nudity and alcohol sharing the same room, but also banning any nudity near schools and churches. The Gold Club did open with nude dancers, but soon folded under the handicap of the no-liquor policy.

"There's nothing immoral about the human body. Evil's all in the mind." [3]

— Griffith, in a 1993 interview

Griffith, meanwhile, successfully changed the Gayety into the all-nude, alcohol-free Deja Vu (without local competition), and turned the Roxy into an adult theater, Club Madonna. Daoud was removed from office a year later after being implicated on unrelated corruption charges for which he was later convicted and imprisoned.[3] Griffith and Daoud have since become close friends.

Since the early 2000s, Griffith has been involved in legal disputes with the City of Miami Beach over its 1989/1990 ordinances banning the sale of alcohol in any establishment featuring nudity. He sued several city officials in federal court, alleging they conspired to deny him a fair hearing before the City Commission after he sued the wife of one commissioner for libel, slander, and defamation after she waged a campaign against him, claiming, among other things, that he was a tax cheat.[118][119][120]

Philanthropy

Griffith, for years, hosted annual shows at his Carib Theater benefiting the Miami Beach Police and Firemen's Benevolent Association. The city's police softball teams and the Miami Beach Policemen's Relief and Pension Fund have also been beneficiaries of his charitable giving. In 1997, the MBPD recognized Griffith for his donation of bicycles to the department, for use by its bike patrol officers.

Nationally-syndicated gossip writer Earl Wilson thanked Griffith in a December 1965 column "for his welcome Christmas check for the 'Earl Wilson Help the Needy Fund' which arrived just in time to aid some deserving folk."[121]

Work

Stage productions

- This Was Burlesque (1964) - producer

- Hello Burlesque - producer

Filmography

- Bell, Bare and Beautiful (1963) - producer, writer, actor (Theater Manager)

- Lullaby of Bareland (1964) - producer

- Mundo depravados (1967) - producer

- My Third Wife, George (1968) - producer

- Behind the Burly Q (documentary, 2010) - interview subject

Awards and recognitions

- 1970s: Key to the City of Miami Beach (awarded by Mayor Harold Rosen)

- 1970s: Recognition for "unselfish contributions" to the annual All-Star show (Miami Beach Police and Firemen's Benevolent Association)

- 1997: Recognition for "outstanding dedication and service" to the Washington Avenue Bike Unit (Miami Beach Police Department)

- 1999: Recognition for "generous support" for the Miami Beach Police softball teams (Miami Beach Police Department)

- 2000: Recognition for "generosity and continued support" (Miami Beach Policemen's Relief and Pension Fund)

- 2007: Best Adult Club in Miami Beach (Club Madonna), The Miami SunPost

References

- ↑ Norman, Forrest (February 2, 2006). "The Battle of Biscayne". The Miami New Times. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Zemeckis, Leslie (2013). "Florida". Behind the Burly Q: The Story of Burlesque in America. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62087-691-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Baker, Greg (January 27, 1993). "The Pioneer of Porn". The Miami New Times. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ Biondi, Joanne (2006). Miami Beach Memories: A Nostalgic Chronicle of Days Gone By. Guilford, Conn.: The Globe Pequot Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0762740666.

- ↑ "Leroy C. Griffith". Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ "Behind the Burly Q". imdb.com. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ "Ann Corio, Star of "This Was Burlesque," Dead". playbill.com. Playbill. March 10, 1999. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Follies Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ "Gem Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ "Rialto Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Loop End Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Capitol Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ritz Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Ritz Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Folly Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Folly Theater". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Strand Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Strand Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Beshouri, Paul (July 16, 2013). "Restored Garden Theater Predicts September Debut". curbed.com. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Garden Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Garden Theater". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "National Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "National Theater". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Michigan Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ↑ "Michigan Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Adam and Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ "Civic Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Village East Cinema". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Hudson Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Hudson Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Arrow Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Shore Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Shore Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Luxor Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Luxor Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cameo Twin Cinema XXX". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Treat Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Rohrer, Jim (Dec 30, 2010). "Burlesque house sendoff". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Empress Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Imperial Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Imperial Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "University Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "University Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Little Art Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Olentangy Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Livingston Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Parsons Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Parsons Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ohio Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Gayety Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Gayety Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Hebert, Lou (February 20, 2010). "A Summer's Night In Downtown Toledo". The Toledo Gazette. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Strand Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Strand Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cayuga Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ McGlinchey, Dennis. "The Theatres of Germantown". www.friendsofimmaculate.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Cayuga Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Howard Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Howard Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cameraphone Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ "Cameraphone Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Blue Mouse Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Capitol Theatre". silentera.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Capitol Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Puget Sound Pipeline: Capitol Theatre". www.pstos.org. Puget Sound Theatre Organ Society. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ "Star Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Star Theater website". startheaterportland.com. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Little Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Little Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Navy Point Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Navy Point Theater". pensapedia.com. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Ritz Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Ritz Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Casino Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Improv Comedy Theater". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Carrollton Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ↑ "Carrollton Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cine Royale Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Cine Royale Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Martin Cinerama Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "New Orleans Martin Cinerama Theatre". incinerama.com. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ "Neighborhood Theater". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Neighborhood Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Capitol Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Capitol Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Central Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Imperial Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Atlas Twin". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Boulevard Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Boulevard Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Cameo Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Cameo Theater". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Carib Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Carib Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Rio Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Dixie Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Flamingo Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Flamingo Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Monroe Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Monroe Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paramount Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Paramount Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paris Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Variety Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Rex Art Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Rosetta Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Roxy Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Roxy Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- 1 2 Wakefield, Rebecca (May 2, 2002). "Strip Wars". The Miami New Times. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ "21st Street Twin". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "21st Street Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Town Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ "Town Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ "79th Street Twin II Cinema". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "79th Street Cinema". cinematour.com. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "Rivoli Theatre". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Branham-Bailey, Charles (August 8, 2013). "For Pete's Sake, Give Madonna A Trial Liquor Period Already". The Miami SunPost. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ Smiley, David (September 25, 2013). "Club Madonna sues Miami Beach, again". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ↑ Branham-Bailey, Charles (November 14, 2013). "If It Walks and Quacks Like One, It's Extortion". The Miami SunPost. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Wilson, Earl (December 27, 1965). "This Is Gratitude, You Newsmakers of 1965". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

External links

- Leroy Griffith at the Internet Movie Database

- "Behind The Burly Q"

- Club Madonna

- Sex, Money, Politics in Miami Beach (CBS4 I-Team report)

- Wonderland

- The World of Leroy Griffith blog