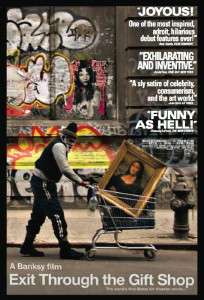

Exit Through the Gift Shop

| Exit Through The Gift Shop | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Banksy |

| Produced by |

Holly Cushing Jaimie D'Cruz James Gay-Rees |

| Starring |

Thierry Guetta Banksy Shepard Fairey Invader André |

| Narrated by | Rhys Ifans |

| Music by | Geoff Barrow |

| Edited by |

Tom Fulford Chris King |

Production company |

Paranoid Pictures |

| Distributed by |

Revolver Entertainment (UK) Producers Distribution Agency (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language |

|

| Box office | $5,308,618.2 |

Exit Through the Gift Shop: A Banksy Film is a 2010 British documentary film directed by street artist Banksy. It tells the story of Thierry Guetta, a French immigrant in Los Angeles, and his obsession with street art. The film charts Guetta's constant documenting of his every waking moment on film, from a chance encounter with his cousin, the artist Invader, to his introduction to a host of street artists with a focus on Shepard Fairey and Banksy, whose anonymity is preserved by obscuring his face and altering his voice, to Guetta's eventual fame as a street artist himself. It is narrated by Rhys Ifans. The music is by Geoff Barrow. It includes Richard Hawley's "Tonight The Streets Are Ours".[1]

The film premiered at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival on 24 January 2010, and it was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Since its release, there has been extensive debate over whether the documentary is genuine or a mockumentary, although Banksy answered "Yes" when asked if the film is real.[2]

Synopsis

Thierry Guetta is a French immigrant living in Los Angeles who runs a vintage clothing shop. He also has an obsession with carrying a camera everywhere and constantly filming his surroundings. On a holiday in France, he discovers his cousin is Invader, an internationally known street artist. Thierry finds this fascinating, and accompanies Invader and his friends, including the artists Monsieur André and Zevs on their nocturnal adventures, documenting their activities. A few months later, Invader visits Thierry in LA, and arranges a meeting with Shepard Fairey. Thierry continues filming Fairey's activities even after Invader has returned home to France. While Fairey is confused by Thierry's enthusiasm, Thierry states that he wishes to make a complete documentary about street art, and the two cross the nation, filming other artists at work, including Poster Boy, Seizer, Neck Face, Sweet Toof, Cyclops, Ron English, Dotmasters, Swoon, Azil, Borf and Buffmonster. What Guetta fails to tell Fairey is that he has no plan to compile his footage into an actual film, and never looks at his footage.

Guetta continues to hear more about Banksy – a prominent and particularly secretive artist. His attempts to contact Banksy are unsuccessful, until one day Banksy visits LA without his usual accomplice, who is refused entry to the US. Stuck in LA without a guide, Banksy contacts Fairey, who calls Guetta. Guetta becomes Banksy's guide in LA, later following him back to England, winning the privilege to film Banksy on his home turf – a feat that confuses Banksy's crew. Banksy, however, sees the opportunity to document street art, which he recognizes as having a "short life span", and after Guetta aids him in recording both production, deployment and crowd reactions to his "Murdered Phone-box" piece, asks him to film the preparations for his "Barely Legal" show. The two become friends, as Guetta provides Banksy with some relief from his anonymity. Returning to LA, Guetta becomes bored, and eventually produced his own stickers and decals, putting them up in the city.

Banksy's show is being prepared in Skid Row, Los Angeles, and while in LA, Banksy decides deploying a Guantanamo Bay detainee doll in Disneyland. He visits the location and places the doll while Guetta films it. A short while later, however, the rides stop, and the park's security catch Guetta, who is taken to an interrogation room, while Banksy switches clothes and blends into the crowd. During interrogation, Guetta refuses to admit any wrongdoing, and when allowed a phone call, covertly alerts Banksy to his situation. When confronted by security personnel, he destroys the evidence in his stills camera, but stashes the videotape in his sock and is eventually let go, much to the amazement of Banksy who then says he trusts him implicitly because of the incident.

A few days later, "Barely Legal" opens, and becomes an overnight success. Street art prices begin to rocket in auction houses. Banksy is stunned by the sudden hype surrounding street art, and urges Guetta to finish his supposed documentary. Guetta begins to edit together the several thousand hours of footage, and produces a film titled Life Remote Control. The result is 90 minutes of distorted fast cutting about random themes. Banksy questions Guetta's ability as a filmmaker, deeming his product "unwatchable", but realizes the street art footage itself is valuable. Banksy decides to try producing a film himself. To ensure that Guetta remains occupied, Banksy suggests he makes his own art show.

"I think the joke is on... I don’t know who the joke is on, really. I don’t even know if there is a joke."

— Banksy's former spokesman Steve Lazarides

Guetta accepts the assignment, adopting the name "Mr. Brainwash", putting up street art in the city and six months later, re-mortgaging his business to afford renting copious equipment and a complete production team to create pieces of art under his supervision. He rents a former CBS studio to prepare his first show, "Life Is Beautiful", and scales up his production to something much larger than Banksy suggested, but with little focus. When Guetta breaks his foot after falling off a ladder, Banksy realises that the show may become a trainwreck, and sends a few professionals to help Guetta out. While the producers take care of the practical side of the show, Guetta spends his time on more publicity, asking support from both Fairey and Banksy, eventually taping up huge billboards with their quotes, and ultimately ending up on the cover of L. A. Weekly. Preparation is seriously behind schedule, and Guetta's production team insists that he must make decisions—yet Guetta spends his time hyping up and marketing his work for tens of thousands of dollars. Eight hours before the opening, paintings are still missing from the walls, and since Guetta is busy giving interviews, the eventual layout of the show is decided by the crew itself.

Despite all this, however, the show becomes a raging success with the crowd, and after the first week of the show, Guetta sells almost a million dollars worth of art, with his pieces showing in galleries all around the world, to the utter confusion of both Fairey and Banksy. In an ending montage, Guetta insists that time will tell whether he is a real artist or not.

Production

Banksy has said in interviews that editing the film together was an arduous process, noting that "I spent a year [...] watching footage of sweaty vandals falling off ladders"[3] and "The film was made by a very small team. It would have been even smaller if the editors didn't keep having mental breakdowns. They went through over 10,000 hours of Thierry's tapes and got literally seconds of usable footage out of it."[4] Producer Jaimie D'Cruz wrote in his production diary that obtaining the original tapes from Thierry was particularly complicated.

Reception and hoax speculation

Film industry veterans John Sloss and Bart Walker founded a new distribution company to release the film in the US, Producers Distribution Agency (PDA).[5] With a unique grassroots campaign, PDA brought the film to a US theatrical gross of $3.29MM.[6] The film received overwhelmingly positive reviews, holding 96% on Rotten Tomatoes, and was nominated for Best Documentary in the 2011 Academy Awards.[7] One consistent theme in the reviews was the authenticity of the film: Was the film just an elaborate ruse on Banksy's part, or did Guetta really evolve into Mr. Brainwash overnight? The Boston Globe movie reviewer Ty Burr found it to be quite entertaining and awarded it four stars. He dismissed the notion of the film being a "put on", saying that "I'm not buying it; for one thing, this story’s too good, too weirdly rich, to be made up. For another, the movie’s gently amused scorn lands on everyone."[8] Roger Ebert gave it 3.5 stars out of 4, writing: "The widespread speculation that 'Exit Through the Gift Shop' is a hoax only adds to its fascination."[9] In an interview with SuicideGirls,[10] filmmakers Jaimie D'Cruz and Chris King denied that it was a hoax, and expressed their growing frustration with the speculation that it was: "For a while we all thought that was quite funny, but it went on for so long. It was a bit disappointing when it became basically accepted as fact, that it was all just a silly hoax ... I felt it was a shame that the whole thing was going to be dismissed like that really – because we knew it was true."[11]

The New York Times movie reviewer Jeannette Catsoulis wrote that the film could be a new subgenre, a "prankumentary".[12]

Guetta in an interview said: "This movie is 100% real. Banksy captured me becoming an artist. In the end, I became his biggest work of art."[13]

Guetta faced copyright issues following the release of the film. Glen Friedman, a prominent American photographer,[14] successfully sued Guetta over the use of a photograph of the rap group Run DMC.[15] Guetta tried to claim that he had altered it enough to be considered an original piece of art. However the presiding judge over the case, Judge Pregerson, ultimately ruled Friedman’s photograph was protected under the transformative fair use law. Guetta also faced copyright claims from Joachim Levy, a Swiss filmmaker, who edited and produced Guetta’s film Life Remote Control,[16] clips of which were shown in the film. Levy was not credited for his work he did on the film, however Guetta owned the footage which was then licensed to Banksy.[16]

New York Film Critics Online bestowed its Best Documentary Award on the film in 2010. French journalist Marjolaine Gout gave it 4 stars out of 5, linking Mr. Brainwash and Jeff Koons and criticizing Thierry Guetta's art as toilet papering.[17]

Oscilloscope Laboratories released Exit Through the Gift Shop on DVD and Blu-ray in 2011.[18]

Archival footage

The film's opening montage features archival footage from notable street art films from across the world. Films include Dirty Hands: The Art and Crimes of David Choe, Infamy, Megpoid, Next, Open Air, The Lyfe, Popaganda: The Art and Crimes of Ron English, Rash, Restless Debt of the Third World, Spending Time, Turf War, Elis G The Life of a Shadow, Memoria Canalla, C215 in London, Beautiful Losers.[19]

References

Notes

- ↑ Willmore, Alison, "Exit Through The Gift Shop: It's a madhouse, this modern life.", The Independent Eye, IFC reviews of the Sundance Film Festival, 27 January 2010

- ↑ "Frequently asked questions". Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ Kylie Northover (29 May 2010). "Drawn from the shadows, wanted man comes out to play". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ Shelley Leopold. "Banksy Revealed?".

- ↑ ""Exit" Strategy: Bringing Banksy to the Masses". indiewire.com. 7 April 2010.

- ↑ "Box Office Mojo box office results". boxofficemojo.com.

- ↑ "Oscar nominations 2011: Complete list of Academy Award nominees". The Washington Post. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ↑ Burr, Ty, "Exit Through the Gift Shop: Writing’s on the wall: In ‘Exit,’ street art scene becomes a farce", The Boston Globe, 23 April 2010

- ↑ "Exit Through the Gift Shop". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ "Jaimie D'Cruz and Chris King: Exit Through the Gift Shop". SuicideGirls.com. 14 Dec 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2011..

- ↑ "Jaimie D'Cruz and Chris King: Exit Through the Gift Shop". SuicideGirls.com. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ↑ Catsoulis, Jeannette, "On the Street, at the Corner of Art and Trash", The New York Times, 16 April 2010."“Exit” could be a new subgenre: the prankumentary. Audiences, however, would be advised simply to enjoy the film on its face — even if that face is a carefully contrived mask."

- ↑ Felch, Jason, "Getting at the truth of 'Exit Through the Gift Shop'", The Los Angeles Times, 22 February 2011.

- ↑ Friedman, Glen, Glen E. Friedman#Books and exhibitions with significant Friedman contributions (partial listing)4

- ↑ Run DMC Photograph

- 1 2 The New York Times, Life Remote Control footage lawsuit

- ↑ "Review of Exit Through the Gift Shop". Ecranlarge (in French).

- ↑ "Oscilloscope to Release Banksy DVD". Variety.

- ↑ Credits, 'Archival footage', Exit Through the Gift Shop.

Further reading

- "Banksy film to debut at Sundance". BBC News. BBC. 21 January 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Knegt, Peter (21 January 2010). "Sundance Surprise: Banksy's "Gift Shop"". indieWire. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- "Sundance 2010: Banksy rocks festival with 'Gift Shop'". Los Angeles Times. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "FILM REVIEW: Exit Through The Gift Shop". Culture Northern Ireland. 9 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Jackson, Candace; Schuker, Lauren A. E., "Mr. Brainwash: For Real?", The Wall Street Journal, 12 February 2010.

- Ryzik, Melena, "Riddle? Yes. Enigma? Sure. Documentary?", The New York Times, 13 April 2010.

- Michael Hutak, Exit Through the Foyer. Review of Australian première at the 2010 Sydney Film Festival; critiques the film for posing as hoax.

External links

- Official website

- Exit Through the Gift Shop at the Internet Movie Database

- Exit Through the Gift Shop at Rotten Tomatoes

- 'Shenanigans Are What He Does': Is Banksy Gunning For An Oscar? – audio report by NPR

- Exit Through the Gift Shop: Cavemen to the Right Film Review, Bright Lights Film Journal