Lime (fruit)

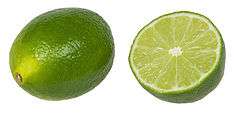

A lime (from French lime, from Arabic līma, from Persian līmū, "lemon")[1] is a hybrid citrus fruit, which is typically round, lime green, 3–6 centimetres (1.2–2.4 in) in diameter, and containing acidic juice vesicles.[2] There are several species of citrus trees whose fruits are called limes, including the Key lime (Citrus aurantifolia), Persian lime, kaffir lime, and desert lime. Limes are an excellent source of vitamin C, and are often used to accent the flavours of foods and beverages. They are grown year-round.[3] Plants with fruit called "limes" have diverse genetic origins; limes do not form a monophyletic group.

Plants known as "lime"

- Australian limes (former Microcitrus and Eremocitrus)

- Australian desert lime (Citrus glauca)

- Australian finger lime (Citrus australasica)

- Australian round lime (Citrus australis)

- Blood lime (red finger lime x (sweet orange x mandarin) )

- Kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix); also called a kieffer lime, makrut, or magrood; a papeda relative.

- Key lime (Citrus aurantifolia=Citrus micrantha x Citrus medica[4][5][6]); also called Mexican, West Indian, or bartender's lime.

- Musk lime (Citrofortunella mitis), a kumquat hybrid

- Persian lime (Citrus x latifolia), also called Tahiti or Bearss lime. Developed in California, this is the commonplace lime.[7]

- Rangpur lime (Mandarin lime, lemandarin[8]), a mandarin orange – rough lemon[4] hybrid

- Spanish lime (Melicoccus bijugatus); also called mamoncillo, mamón, ginep, quenepa, or limoncillo); not a citrus.

- Sweet lime etc. (Citrus limetta etc.); assorted citrus hybrids) including varieties called sweet lemon, sweet limetta or Mediterranean sweet lemon, lumia, Indian or Palestinian sweet lime.

- Wild lime (Adelia ricinella); not a citrus.

- Wild lime (Zanthoxylum fagara); not a citrus.

- Limequat (lime × kumquat)

The tree species known in Britain as lime trees (Tilia sp.), called linden in other dialects of English, are broadleaf temperate plants, unrelated to the citrus fruits.

History

Although the precise origin is uncertain, limes are believed to have first grown in Indonesia or Southeast Asia, then were transported to the Mediterranean region and northern Africa around 1000.[2]

To prevent scurvy during the 19th century, British sailors were issued a daily allowance of citrus, such as lemon, and later switched to lime.[9] The use of citrus was initially a closely guarded military secret, as scurvy was a common scourge of various national navies, and the ability to remain at sea for lengthy periods without contracting the disorder was a huge benefit for the military. The British sailor thus acquired the nickname, "Limey" because of their usage of limes.[10]

Production

| Lemon and lime production – 2013 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

In 2013, the total world production of lemons and limes was 15.42 million tonnes, with India leading production of 2.52 million tonnes (table).

Uses

Limes have higher contents of sugars and acids than do lemons.[2]

Lime juice may be squeezed from fresh limes, or purchased in bottles in both unsweetened and sweetened varieties. Lime juice is used to make limeade, and as an ingredient (typically as sour mix) in many cocktails.

Lime pickles are an integral part of Indian cuisine. South Indian cuisine is heavily based on lime; having either lemon pickle or lime pickle is considered an essential of Onam Sadhya.

In cooking, lime is valued both for the acidity of its juice and the floral aroma of its zest. It is a common ingredient in authentic Mexican, Vietnamese and Thai dishes. It is also used for its pickling properties in ceviche. Some guacamole recipes call for lime juice.

The use of dried limes (called black lime or loomi) as a flavouring is typical of Persian cuisine and Iraqi cuisine, as well as in Persian Gulf-style baharat (a spice mixture that is also called kabsa or kebsa).

Lime is an ingredient of many cuisines from India, and many varieties of pickles are made, e.g. sweetened lime pickle, salted pickle, and lime chutney.

Key lime gives the character flavoring to the American dessert known as Key lime pie. In Australia, desert lime is used for making marmalade.

Lime is an ingredient in several highball cocktails, often based on gin, such as gin and tonic, the gimlet and the Rickey. Freshly squeezed lime juice is also considered a key ingredient in margaritas, although sometimes lemon juice is substituted.

Lime extracts and lime essential oils are frequently used in perfumes, cleaning products, and aromatherapy.

Nutrition and research

|

Limes, whole and in cross section | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 126 kJ (30 kcal) |

|

10.5 g | |

| Sugars | 1.7 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2.8 g |

|

0.2 g | |

|

0.7 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(3%) 0.03 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(2%) 0.02 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(1%) 0.2 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(4%) 0.217 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(4%) 0.046 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(2%) 8 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(35%) 29.1 mg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(3%) 33 mg |

| Iron |

(5%) 0.6 mg |

| Magnesium |

(2%) 6 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(3%) 18 mg |

| Potassium |

(2%) 102 mg |

| Sodium |

(0%) 2 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 88.3 g |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Raw limes are 88% water, 10% carbohydrates and less than 1% each of fat and protein (table). Only vitamin C content at 35% of the Daily Value (DV) per 100 g serving is significant for nutrition, with other nutrients present in low DV amounts (table).

Phytochemicals

Lime flesh and peel contain diverse phytochemicals, including polyphenols and terpenes,[12] many of which are under basic research for their potential properties in humans.[13]

Dermatitis

When human skin is exposed to ultraviolet light after contact with lime peel or juice, a reaction known as phytophotodermatitis can occur, which can cause darkening of the skin, swelling or blistering. Bartenders handling limes and other citrus fruits when preparing cocktails may develop phytophotodermatitis due to the high concentration of furocoumarins and other phototoxic coumarins in limes.[14] The main coumarin in limes is limettin which has manifold higher content in peels than in pulp.[15][16] Persian limes have a higher content of coumarins and potentially greater phototoxicity than do Key limes.[15]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lime. |

- Lime production in Mexico

- List of citrus fruits

- List of lime cultivars

- List of culinary fruits varieties

- Pickled lime

References

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary

- 1 2 3 "Lime". Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Rotter, Ben. "Fruit Data: Yield, Sugar, Acidity, Tannin". Improved Winemaking. Retrieved 2014-09-03.

- 1 2 Curk, Franck; Ancillo, Gema; Garcia-Lor, Andres; Luro, François; Perrier, Xavier; Jacquemoud-Collet, Jean-Pierre; Navarro, Luis; Ollitrault, Patrick (2014). "Next generation haplotyping to decipher nuclear genomic interspecific admixture in Citrus species: analysis of chromosome 2". BMC Genetics. 15. doi:10.1186/s12863-014-0152-1.

- ↑ Li, Xiaomeng; Xie, Rangjin; Lu, Zhenhua; Zhou, Zhiqin (July 2010). "The Origin of Cultivated Citrus as Inferred from Internal Transcribed Spacer and Chloroplast DNA Sequence and Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Fingerprints". Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Wall, Tim (18 January 2011). "Citrus Fruit Gets Paternity Test". Discovery.com. Discovery. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Plattner, Kristy (26 September 2014). "Fruit and Tree Nuts Outlook: Economic Insight" (PDF). USDA Economic Research Service.

- ↑ "Australian Blood Lime". homecitrusgrowers.co.uk.

- ↑ "State of knowledge about scurvy". Section of the History of Medicine, publisher not shown. 3 February 1971. PMC 1644345

.

. - ↑ "Limey". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ "Production/Crops/World for lemons and limes, 2013". Food And Agricultural Organization of United Nations, Statistics Division. 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ Loizzo MR, Tundis R, Bonesi M, Menichini F, De Luca D, Colica C, Menichini F (2012). "Evaluation of Citrus aurantifolia peel and leaves extracts for their chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-cholinesterase activities". J Sci Food Agric. 92 (15): 2960–7. doi:10.1002/jsfa.5708. PMID 22589172.

- ↑ Patil JR, Chidambara Murthy KN, Jayaprakasha GK, Chetti MB, Patil BS (2009). "Bioactive compounds from Mexican lime ( Citrus aurantifolia ) juice induce apoptosis in human pancreatic cells". J Agric Food Chem. 57 (22): 10933–42. doi:10.1021/jf901718u. PMID 19919125.

- ↑ L. Kanerva (2000). Handbook of Occupational Dermatology. Springer. p. 318. ISBN 978-3-540-64046-2.

- 1 2 Nigg HN, Nordby HE, Beier RC, Dillman A, Macias C, Hansen RC (1993). "Phototoxic coumarins in limes". Food Chem Toxicol. 31 (5): 331–5. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(93)90187-4. PMID 8505017.

- ↑ Gorgus E, Lohr C, Raquet N, Guth S, Schrenk D (2010). "Limettin and furocoumarins in beverages containing citrus juices or extracts". Food Chem Toxicol. 48 (1): 93–8. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.09.021. PMID 19770019.