Capital punishment by the United States federal government

The United States federal government (in comparison to the separate states) applies the death penalty for crimes: treason, terrorism, espionage, federal murder, large-scale drug trafficking, and attempting to kill a witness, juror, or court officer in certain cases. Military law allows execution of soldiers for several crimes. Executions by the federal government have been rare compared to those by state governments. Twenty-six federal (including military) executions have been carried out since 1950. Three of those (none of them military) have occurred in the modern post-Gregg era. This list only includes those executed under federal jurisdiction. The Federal Bureau of Prisons manages the housing and execution of federal death row prisoners. As of January 19, 2014, fifty-nine people were on the federal death row for men at the Federal Correctional Complex in Terre Haute, Indiana; while the two women on the federal death row were at Federal Medical Center, Carswell in Fort Worth, Texas.[1]

From 1776 until 2009 340 people were executed by the federal government, a figure smaller than that of the State of Texas post-Furman v. Georgia.[2] In 2004 John Brigham, author of "Unusual Punishment: The Federal Death Penalty in the United States," wrote that "the score of prisoners on federal death row are in some respects little more than a footnote."[3]

History

The Crimes Act of 1790 created six capital offenses: treason, counterfeiting, three variations of piracy or felonies on the high seas, and aiding the escape of a capital prisoner.[4] The first federal execution was that of Thomas Bird on June 25, 1790 due to his committing "murder on the high seas".[5]

The use of the death penalty in U.S. territories was handled by federal judges and the U.S. Marshal Service.

The capital punishment was halted in 1972 after the Furman v. Georgia decision, but was once again permitted under the Gregg v. Georgia decision in 1976.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 restored the death penalty under federal law for drug offenses and some types of murder.[6] U.S. President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, expanding the federal death penalty in 1994.[7] In response to the Oklahoma City bombing, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 was passed in 1996. Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute became the only federal prison to execute people and one of only two prisons to hold federally condemned people.

Pre-Furman executions by the federal government were normally carried out within the prison system of the state where the crime was committed. Only in cases where the crime was committed in a territory, in the District of Columbia or in a state without the death penalty was it the norm for the court to designate the state in which the death penalty would be carried out, as the federal prison system lacked an execution facility.

In the late 1980s U.S. senator Alfonse D'Amato, from New York State, began sponsoring a bill to make certain drug crimes federal death penalty crimes as he was frustrated by the lack of application of the death penalty from his respective state government.[8] Prior to the 1990s bills, federal death penalty cases only covered crimes not in state criminal codes such as treason. Since the 1990s some federal death penalty laws cover some acts already covered under state criminal codes.[9] However before 2001, the federal attorneys had a manual stating that there would be no reason to seek a federal death penalty in a state that does not have its own death penalty, and until that point federal attorneys never pursued capital punishment in states without their own death penalties.[8] Marvin Gabrion, who committed his crime in Michigan, became the first post-Furman person in a non-death penalty state to receive the federal death penalty; he was sentenced on March 16, 2002. By October 2009 federal authorities gave death sentences to eight other persons from non-death penalty states.[10] Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who committed his crime in non-death penalty state Massachusetts, received a federal death sentence in 2015.[11]

Timothy McVeigh was executed on June 11, 2001, for his involvement in the Oklahoma City bombing. It was the first federal execution since 1963. Other executions by the United States include Juan Raul Garza on June 19, 2001, and Louis Jones Jr. on March 18, 2003. Sentences of death are now handed down by the jury, and the judge lacks discretion to reject the recommendation.[12]

The use of the federal death penalty increased in the 2000s, with the number of those sentenced to death federally climbing from 18 to 50 by 2007. Most such sentences were given in states which have active death state penalty statutes, with the largest number of federal death sentences handed down in Texas, which actively executed criminals. However U.S. attorneys increasingly began pursuing death sentences in states with no state death penalties and/or with inactive state death penalties. In federal trials the courts may exclude jurors who are opposed to the death penalty, even in trials taking place in non-death penalty states.[8] In 2004 Brigham stated that due to an increase of federal death penalty verdicts in the preceding decade, "some fear a “federalization” of the death penalty is taking place".[3]

As of May 14, 2010, 52 male federal death row prisoners were housed at United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute.[13] As of 2010, the two women on federal death row, Angela Johnson and Lisa M. Montgomery, were held at Federal Medical Center, Carswell.[14][15][16] Some male death row inmates are instead held at ADX Florence.[17] Two people have been re-sentenced since 1976 to life in prison and one had the sentence commuted to life in prison by President Bill Clinton in 2001.

As of 2015 only three federal death row prisoners had been executed since 1988.[18]

Legal process

Sentencing

In the federal system, the final decision to seek or not the death penalty belongs to United States Attorney General. This differs from the particular states, where local prosecutors have the final say on that with no involvement from the state attorney general.[19]

The sentence is decided by the jury and must be unanimous.

In case of a hung jury during the penalty phase of the trial, a life sentence is issued, even if a single juror opposed death (there is no retrial).[20]

Appeals

While death row inmates sentenced by state governments may appeal to both state courts and federal courts, federal death row inmates may only appeal to federal courts; this gives them fewer avenues of appeal.[21]

The power of clemency belongs to the President of the United States.

Capital offenses

These are the offenses punishable by life imprisonment or death under United States Code:[22]

- Causing death by using a chemical weapon or a weapon of mass destruction

- Killing a member of the Congress, the Cabinet or United States Supreme Court

- Kidnapping a member of the Congress, the Cabinet or Supreme Court resulting in death

- Conspiracy to kill a member of the Congress, the Cabinet or Supreme Court resulting in death

- Causing death by using an explosive

- Causing death by using an illegal firearm

- Causing death during a drug-related drive-by shooting

- Genocide resulting in death

- Carjacking resulting in death

- Willful destruction of aircraft or motor vehicles resulting in death.

- Causing death by aircraft hijacking or any attempt to commit aircraft hijacking.

- Causing death by kidnapping or hostage taking.

- First degree murder

- Murder perpetrated by poison or lying in wait

- Murder that is willful, deliberate, malicious, and premeditated

- Murder in the perpetration of, or in the attempt to perpetrate, any arson, torture, escape, kidnapping, treason, espionage, sabotage, aggravated sexual abuse or sexual abuse, child abuse, burglary, or robbery.

- Murder perpetrated as part of a pattern or practice of assault or torture against a child or children

- Murder committed by a federal prisoner or an escaped federal prisoner sentenced to 15 years to life or a more severe penalty

- Assassinating the President or a member of his staff

- Kidnapping the President or a member of his staff resulting in death

- Killing persons aiding Federal investigations or State correctional officers

- Willful wrecking of a train resulting in death

- Sexual abuse resulting in death

- Sexual exploitation of children resulting in death

- Torture resulting in death

- War crimes resulting in death

- Large-scale drug trafficking (like high-level selling of marijuana)

- Attempting, authorizing or advising the killing of any officer, juror, or witness in cases involving a Continuing Criminal Enterprise, even if such killing does not occur.

- Espionage

- Treason

Method

Under current law, federal executions occur at United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute by lethal injection. Federal judges are permitted to relocate individual executions from USP Terre Haute to a prison in a state where the death penalty is legal. They may do this to make it more convenient for victims and/or family members of persons involved in the relevant cases.[23]

Historically members of the U.S. Marshalls Service conducted federal executions. Hanging was the primary method of death until the mid-20th century.[5] The federal prison system never operated its own gas chamber or electric chair for pre-Furman executions. Pre-Furman executions carried out within the federal prison system were by hanging. All federally mandated executions by lethal gas or electrocution were carried out in state prisons.

People who are under 18 at the time of commission of the capital crime [24] or intellectually disabled[25] are legally precluded from being executed.

Post-Furman executions

Three executions (none of them military) have occurred in the modern post-Gregg era. This list only includes those executed under federal jurisdiction. Since 1963, three people have been executed by the federal government of the United States. All were executed by lethal injection at USP Terre Haute.

| Executed person | Date | Crime | State where crime occurred | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Timothy McVeigh | June 11, 2001 | Murder of eight federal law enforcement officers through the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. | Oklahoma |

| 2 | Juan Raul Garza | June 19, 2001 | Murder of Thomas Albert Rumbo, ordering the murders of Gilberto Matos, Erasmo De La Fuente, Antonio Nieto, Bernabe Sosa, Diana Flores Villareal, Oscar Cantu, and Fernando Escobar Garcia in conjunction with a drug-smuggling ring | Texas |

| 3 | Louis Jones, Jr. | March 18, 2003 | Rape and murder of Pvt. Tracie McBride, USA | Texas |

Presidential assassins

| Executed person | Date of execution | Method | President Assassinated | Under President |

|---|---|---|---|---|

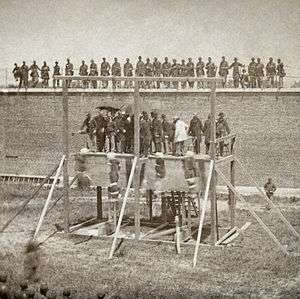

| George Atzerodt | July 7, 1865 | hanging | Abraham Lincoln | Andrew Johnson |

| David Herold | July 7, 1865 | hanging | Abraham Lincoln | Andrew Johnson |

| Lewis Powell | July 7, 1865 | hanging | Abraham Lincoln | Andrew Johnson |

| Mary Surratt | July 7, 1865 | hanging | Abraham Lincoln | Andrew Johnson |

| Charles J. Guiteau | June 30, 1882 | hanging | James Garfield | Chester A. Arthur |

The assassinations of Lincoln and Garfield were prosecuted by the federal government because they took place in the District of Columbia. Guiteau's trial was held in D.C. court while the trial of the Lincoln conspirators was held in a special military tribunal. The assassin of William McKinley, Leon Czolgosz, was tried and executed for murder by New York state authorities. The accused assassin of John F. Kennedy, Lee Harvey Oswald, would presumably have been tried for murder by Texas state authorities had he not been killed two days later by Jack Ruby in the basement of the Dallas Municipal Building (then Dallas Police Department headquarters) while being transferred to the county jail. (Ruby himself was initially tried and convicted of murder in a Texas state court, but that was overturned by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and he died before he could be retried.) Only after Kennedy's death was it made a federal crime to murder the President of the United States.

Military executions

The United States military has executed 135 people since 1916. The most recent person to be executed by the military is U.S. Army Private John A. Bennett, executed on April 13, 1961 for rape and attempted murder. Since the end of the Civil War in 1865, only one person has been executed for a purely military offense: Private Eddie Slovik, who was executed on January 31, 1945 after being convicted of desertion.

See also

- Capital punishment in the United States

- Capital punishment for drug trafficking

- List of individuals executed by the United States federal government

- List of death row inmates in the United States

References

- ↑ Federal Death Row Prisoners, Death Penalty Information Center, January 19, 2014

- ↑ Tirschwell, Eric A. and Theodore Hertzberg (both of Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP). "Politics and Prosecutions: A Historical Perspective on Shifting Federal Standards for Pursuing the Death Penalty in non-Death Penalty States." Journal of Constitutional Law. October 2009. Volume 12 Issue 1. p. 57-98. CITED: p. 59.

- 1 2 Brigham, John (University of Massachusetts). "Unusual Punishment: The Federal Death Penalty in the United States." Washington University Journal of Law & Policy. January 2004. Volume 16 (Access to Justice: The Social Responsibility of Lawyers | New Federalism). p. 195-233. See profile page. CITED: p. 212.

- ↑ Crimes Act of 1790, ch. 9, §§ 1, 3, 8–10, 14, 23, 1 Stat. 112, 112–15, 117.

- 1 2 "History - Historical Federal Executions ." U.S. Marshals Service. Retrieved on July 20, 2016.

- ↑ (Pub.L. 100–690, 102 Stat. 4181, enacted November 18, 1988, H

.R ). 5210 - ↑ H

.R , Pub.L. 103–322. 3355 - 1 2 3 Greenblatt, Alan. "Death From Washington." Governing. May 2007. Retrieved on June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Shapiro, Bruce. "What’s Wrong With the Federal Death Penalty." The Nation. May 19, 2015. Retrieved on March 23, 2016.

- ↑ Tirschwell, Eric A. and Theodore Hertzberg (both of Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP). "Politics and Prosecutions: A Historical Perspective on Shifting Federal Standards for Pursuing the Death Penalty in non-Death Penalty States." Journal of Constitutional Law. October 2009. Volume 12 Issue 1. p. 57-98. CITED: p. 62.

- ↑ McDonald, Charlotte. "Does a death sentence always mean death?" BBC. May 23, 2015. Retrieved on July 20, 2016.

- ↑ 18 U.S.C. § 3594; see also U.S. v. Henderson, 485 F.Supp.2d 831, 857 (S.D. Ohio 2007) (recognizing that jury's "recommendation" is binding on the court).

- ↑ "The Bureau Celebrates 80th Anniversary Archived May 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.." Federal Bureau of Prisons. May 14, 2010. Retrieved on October 3, 2010.

- ↑ "DAVID PAUL HAMMER, PETITIONER v. JOHN D. ASHCROFT, ET AL.." U.S. Department of Justice. 14 (18/30). Retrieved on December 15, 2010. "If a media-access policy were to cover the two female death-sentenced inmates in the federal system, it would have to be issued by the warden at the Federal Medical Center in Carswell, Texas, where they are housed."

- ↑ "Lisa M Montgomery." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on October 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Angela Johnson." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on October 14, 2010.

- ↑ Sargent, Hillary and Dialynn Dwyer. "Tsarnaev moved to supermax prison. Here’s how he’ll live" (Archive). Boston Globe. July 17, 2015. Retrieved on December 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Few federal inmates on death row have been executed." CNN. May 15, 2015. Retrieved on March 24, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Attorneys' Manual » Title 9: Criminal - 9-10.000 - Capital Crimes". justice.gov. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Section 3594 - Imposition of a sentence of death". law.justia.com. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Potter, Kyle. "Dru Sjodin’s killer drags out death row delays ." Associated Press at the Twin Cities Pioneer Press. March 22, 2014. Retrieved on June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Title 18 Chapter 228, U.S. Code

- ↑ "The plan to kill Tsarnaev" (Archive). Boston Globe. April 9, 2015. Retrieved on December 13, 2015.

- ↑ Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005)

- ↑ Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002)

Further reading

- Academic articles

- Ross, Jonathan. "The Marriage of State Law and Individual Rights and a New Limit on the Federal Death Penalty." Cleveland State Law Review, 2014. Volume 63, Issue 101. p. 101-146 (46 pages in document).

- Texts of relevant laws

- Using a chemical weapon where the use causes death

- Killing a member of the congress, the cabinet or Supreme Court, Kidnapping a member of the congress, the cabinet or Supreme Court resulting in death and Conspiracy to kill a member of the congress, the cabinet or Supreme Court resulting in death

- Espionage

- Using an explosive device to knowingly kill a person

- Causing death using an illegal firearm

- Genocide where death results

- First Degree Murder

- Murder by a federal prisoner

- Killing persons aiding Federal investigations or State correctional officers

- Murdering the president or his staff and Kidnapping the president or his staff resulting in death

- Sexual abuse resulting in death

- Sexual exploitation of children resulting in death

- Torture resulting in death

- Treason

- War Crimes Resulting in death