List of model organisms

.jpg)

Drosophila melanogaster, one of the most famous subjects for experiments

This is a list of model organisms used in scientific research.

Viruses

- Phage lambda

- Phi X 174 - its genome was the first ever to be sequenced. The genome is a circle of 11 genes, 5386 base pairs in length.

- SV40

- T4 phage

- Tobacco mosaic virus

- Herpes simplex virus

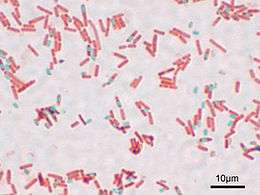

Prokaryotes

Sporulating Bacillus subtilis

- Escherichia coli (E. coli) - This common, Gram-negative gut bacterium is the most widely used organism in molecular genetics.

- Bacillus subtilis - an endospore forming Gram-positive bacterium

- Caulobacter crescentus - a bacterium that divides into two distinct cells used to study cellular differentiation.

- Mycoplasma genitalium - a minimal organism

- Aliivibrio fischeri - quorum sensing, bioluminescence and animal-bacterial symbiosis with Hawaiian bobtail squid

- Synechocystis, a photosynthetic cyanobacterium widely used in photosynthesis research.

- Pseudomonas fluorescens, a soil bacterium that readily diversifies into different strains in the lab.

Eukaryotes

Protists

- Chlamydomonas reinhardtii - a unicellular green alga used to study photosynthesis, flagella and motility, regulation of metabolism, cell-cell recognition and adhesion, response to nutrient deprivation and many other topics. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii has well-studied genetics, with many known and mapped mutants and expressed sequence tags, and there are advanced methods for genetic transformation and selection of genes.[1] Sequencing of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome was reported in October 2007.[2] A Chlamydomonas genetic stock center exists at Duke University, and an international Chlamydomonas research interest group meets on a regular basis to discuss research results. Chlamydomonas is easy to grow on an inexpensive defined medium.

- Dictyostelium discoideum is used in molecular biology and genetics (its genome has been sequenced), and is studied as an example of cell communication, differentiation, and programmed cell death.

- Tetrahymena thermophila - a free living freshwater ciliate protozoan.

- Emiliania huxleyi - a unicellular marine coccolithophore alga, extensively studied as a model phytoplankton species.

- Thalassiosira pseudonana - a unicellular marine diatom alga, extensively studied as a model marine diatom since its genome was published in 2004

Fungi

- Ashbya gossypii, cotton pathogen, subject of genetics studies (polarity, cell cycle)

- Aspergillus nidulans, mold subject of genetics studies

- Coprinus cinereus, mushroom (genetic studies of mushroom development, genetic studies of meiosis)[3]

- Cryptococcus neoformans, opportunistic human pathogen

- Neurospora crassa - orange bread mold (genetic studies of meiosis, metabolic regulation, and circadian rhythm)[4]

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae, baker's yeast or budding yeast (used in brewing and baking)

- Schizophyllum commune - model for mushroom formation.[5]

- Schizosaccharomyces pombe, fission yeast, (cell cycle, cell polarity, RNAi, centromere structure and function, transcription)

- Ustilago maydis, dimorphic yeast and plant pathogen of maize (dimorphism, plant pathogen, transcription)

Plants

- Arabidopsis thaliana, currently the most popular model plant. This herbaceous dicot of the Brassicaceae family is closely related to the mustard plant. Its small stature and short generation time facilitates rapid genetic studies,[6] and many phenotypic and biochemical mutants have been mapped.[6] Arabidopsis was the first plant to have its genome sequenced.[6] Its genome sequence, along with a wide range of information concerning Arabidopsis, is maintained by the TAIR database.[6]

(Plant physiology, Developmental biology, Molecular genetics, Population genetics, Cytology, Molecular biology) - The genus Boechera combines some of the experimental tractability and genetic tools developed for its close relative Arabidopsis with a largely undisturbed natural history, making it a promising model system for research at the intersection of genetics, genomics, ecology, and evolution. The genus includes species with the rare trait of apomixis at the diploid level.[7]

(Evolutionary ecology, Population genetics, Molecular ecology, Evolutionary biology, Ecological genetics, Evolutionary genetics) - Selaginella moellendorffii is a remnant of an ancient lineage of vascular plants that is key to understanding the evolution of land plants. It has a small genome size (~110Mb) and its sequence was released by the Joint Genome Institute in early 2008. (Evolutionary biology, Molecular biology)

- Brachypodium distachyon is an emerging experimental model grass that has many attributes that make it an excellent model for temperate cereals. (Agronomy, Molecular biology, Genetics)

- Setaria viridis is an emerging model grass for C4 photosynthesis and related bioenergy grasses.[8][9]

- Lotus japonicus a model legume used to study the symbiosis responsible for nitrogen fixation. (Agronomy, Molecular biology)

- Lemna gibba is a rapidly growing aquatic monocot, one of the smallest flowering plants. Lemna growth assays are used to evaluate the toxicity of chemicals to plants in ecotoxicology. Because it can be grown in pure culture, microbial action can be excluded. Lemna is being used as a recombinant expression system for economical production of complex biopharmaceuticals. It is also used in education to demonstrate population growth curves.

- Maize (Zea mays L.) is a cereal grain. It is a diploid monocot with 10 large chromosome pairs, easily studied with the microscope. Its genetic features, including many known and mapped phenotypic mutants and a large number of progeny per cross (typically 100-200) facilitated the discovery of transposons ("jumping genes"). Many DNA markers have been mapped and the genome has been sequenced. (Genetics, Molecular biology, Agronomy)

- Medicago truncatula is a model legume, closely related to the common alfalfa. Its rather small genome is currently being sequenced. It is used to study the symbiosis responsible for nitrogen fixation. (Agronomy, Molecular biology)

- Mimulus guttatus is a model organism used in evolutionary and functional genomes studies. The genus Mimulus contains c. 120 species and is in the family Phrymaceae. Several genetic resources have been designed for the study of this genus and some are free access (http://www.mimulusevolution.org)

- Nicotiana benthamiana is often considered a model organism for plant-pathogen studies.[10]

- Tobacco BY-2 cells is a suspension cell line from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) that is useful for general plant physiology studies at the cell level. The genome of this particular cultivar will not be sequenced in the near future, but sequencing of its wild species Nicotiana tabacum is presently in progress. (Cytology, Plant physiology, Biotechnology)

- Rice (Oryza sativa) is used as a model for cereal biology. It has one of the smallest genomes of any cereal species, and sequencing of its genome is finished.[11] (Agronomy, Molecular biology)

- Physcomitrella patens is a moss increasingly used for studies on development and molecular evolution of plants.[12] It is so far the only non-vascular plant(and so the only "primitive" plant) with its genome completely sequenced.[12] Moreover, it is currently the only land plant with efficient gene targeting that enables gene knockout.[13] The resulting knockout mosses are stored and distributed by the International Moss Stock Center. (Plant physiology, Evolutionary biology, Molecular genetics, Molecular biology)

- Marchantia polymorpha is a liverwort that is also emerging as a model for plant biology and development.

- Populus is a genus used as a model in forest genetics and woody plant studies. It has a small genome size, grows very rapidly, and is easily transformed. The genome sequence of black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) is publicly available.[14]

- See also Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, above under Protists.

Animals

Invertebrates

- Amphimedon queenslandica, a demosponge from the phylum Porifera used as a model for evolutionary developmental biology and comparative genomics[15]

- Arbacia punctulata, the purple-spined sea urchin, classical subject of embryological studies

- Aplysia, a sea slug, whose ink release response serves as a model in neurobiology and whose growth cones serve as a model of cytoskeletal rearrangements

- Branchiostoma floridae, a species commonly known as amphioxus or lancelet from the subphylum Cephalochordata of the phylum Chordata used as a model for understanding the evolution of nonchordate deuterostomes, invertebrate chordates, and vertebrates[16]

- Caenorhabditis elegans, a nematode, usually called C. elegans[17] - an excellent model for understanding the genetic control of development and physiology. C.elegans has a fixed number of 1031 cells. C. elegans was the first multicellular organism whose genome was completely sequenced

- Caledia captiva (Orthoptera) in eastern Australia, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Callosobruchus maculatus, the bruchid beetle, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Chorthippus parallelus, the meadow grasshopper, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Ciona intestinalis, a sea squirt

- Daphnia spp., small planktonic crustaceans, highly sensitive to pollution, used for evaluating environmental toxicity of chemicals on aquatic invertebrates.[18]

- Coelopidae - seaweed flies, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Diopsidae - stalk-eyed flies, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Drosophila, usually the species Drosophila melanogaster - a kind of fruit fly, famous as the subject of genetics experiments by Thomas Hunt Morgan and others. Easily raised in lab, rapid generations, mutations easily induced, many observable mutations. Recently, Drosophila has been used for neuropharmacological research.[19] (Molecular genetics, Population genetics, Developmental biology).

- Euprymna scolopes, the Hawaiian bobtail squid, model for animal-bacterial symbiosis, bioluminescent vibrios

- Galleria mellonella (the greater wax moth), the larvae of which are an excellent model organism for in vivo toxicology and pathogenicity testing, replacing the use of small mammals in such experiments.

- Gryllus bimaculatus, the field cricket, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Hydra, a Cnidarian, is the model organism to understand the processes of regeneration and morphogenesis, as well as the evolution of bilaterian body plans[20]

- Loligo pealei, a squid, subject of studies of nerve function because of its giant axon (nearly 1 mm diameter, roughly a thousand times larger than typical mammalian axons)

- Macrostomum lignano, a free-living, marine flatworm, a model organism for the study of stem cells, regeneration, ageing, gene function, and the evolution of sex. Easily raised in the lab, short generation time, indetermined growth, complex behaviour[21]

- Mnemiopsis leidyi, from the phylum Ctenophora (comb jelly) used as a model for evolutionary developmental biology and comparative genomics[22][23]

- Nematostella vectensis, a sea anemone from the phylum Cnidaria used as a model for evolutionary developmental biology and comparative genomics[24][25]

- Oikopleura dioica,[26] an appendicularian, a free-swimming tunicate (or urochordate))

- Oscarella carmela a homoscleromorph sponge (phylum Porifera) used as a model in evolutionary developmental biology[27]

- Parhyale hawaiensis an amphipod crustacean, used in evolutionary developmental (evo-devo) studies, with an extensive toolbox for genetic manipulation.

- Platynereis dumerilii a marine polychaetous annelid, which evolved very slowly and therefore retained many ancestral features.[28]

- Podisma spp. in the Alps, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Pristionchus pacificus, a roundworm used in evolutionary developmental biology in comparative analyses with C. elegans

- Scathophaga stercoraria, the yellow dung fly, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Schmidtea mediterranea a freshwater planarian; a model for regeneration and development of tissues such as the brain and germline

- Stomatogastric ganglion of various arthropod species; a model for motor pattern generation seen in all repetitive motions

- Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, the purple sea urchin, widely used in developmental biology

- Symsagittifera roscoffensis, a flatworm, subject of studies of bilaterian body plan development

- Tribolium castaneum, the flour beetle - a small, easily kept darkling beetle used especially in behavioural ecology experiments

- Trichoplax adhaerens, a very simple free-living animal from the phylum Placozoa used as a model in evolutionary developmental biology and comparative genomics[29]

- Tubifex tubifex, an oligochaeta used for evaluating environmental toxicity of chemicals on aquatic and terrestrial worms.[30]

Vertebrates

Laboratory mice

- Bombina bombina and Bombina variegata, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Carolina anole (Anolis carolinensis), used to study reptile genomics

- Cat (Felis sylvestris catus) - used in neurophysiological research.

- Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) - used for developmental studies, as it is an amniote and excellent for micromanipulation (e.g. tissue grafting) and over-expression of gene products.

- Cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) - formerly used in polio research.

- Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) - an important respiratory and cardiovascular model, also contributed to the discovery of classical conditioning.

- Golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) - first used to study kala-azar (leishmaniasis).

- Guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) - used by Robert Koch and other early bacteriologists as a host for bacterial infections, hence a byword for "laboratory animal" even though less commonly used today.

- Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus)- used to prove echolocation exists in bats in 1930s and also used in experiments predicting microbat behavior as it is a reliable species that has typical features of a temperate bat species.

- Medaka (Oryzias latipes, or Japanese ricefish) - an important model in developmental biology, and has the advantage of being much sturdier than the traditional zebrafish.

- Mouse (Mus musculus) - the classic model vertebrate. Many inbred strains exist, as well as lines selected for particular traits, often of medical interest, e.g. body size, obesity, muscularity, voluntary wheel-running behavior.[31] (Quantitative genetics, Molecular evolution, Genomics)

- Naked mole-rat, (Heterocephalus glaber), studied for their characteristic pain insensitivity, thermoregulation, cancer resistance, eusociality, and longevity.

- Nothobranchius furzeri is studied because of their extreme short-lifespan in research on aging, disease and evolution.

- Pigeon (Columba livia domestica), studied extensively for cognitive science and animal intelligence

- Poecilia reticulata, the guppy, used to study sexual selection and sexual conflict

- Rat (Rattus norvegicus) - particularly useful as a toxicology model; also particularly useful as a neurological model and source of primary cell cultures, owing to the larger size of organs and suborganellar structures relative to the mouse. (Molecular evolution, Genomics)

- Rhesus macaque (or rhesus monkey) (Macaca mulatta) - used for studies on infectious disease and cognition.

- Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) - spinal cord research

- Takifugu (Takifugu rubripes, a pufferfish) - has a small genome with little junk DNA.

- Three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), a fish used to study ethology and behavioral ecology.

- Xenopus tropicalis and Xenopus laevis (African clawed frog) - eggs and embryos from these frogs are used in developmental biology, cell biology, toxicology, and neuroscience[32][33]

- Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) - used in the study of the song system of songbirds and the study of non-mammalian auditory systems.

- Zebrafish (Danio rerio, a freshwater fish) - has a nearly transparent body during early development, which provides unique visual access to the animal's internal anatomy. Zebrafish are used to study development, toxicology and toxicopathology,[34] specific gene function and roles of signaling pathways.

References

- ↑ Chlamydomonas reinhardtii resources at the Joint Genome Institute

- ↑ Chlamydomonas genome sequenced published in Science, October 12, 2007

- ↑ Kües U (June 2000). "Life history and developmental processes in the basidiomycete Coprinus cinereus". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64 (2): 316–53. doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.2.316-353.2000. PMC 98996

. PMID 10839819.

. PMID 10839819. - ↑ Davis, Rowland H. (2000). Neurospora: contributions of a model organism. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512236-4.

- ↑ Ohm, R.; De Jong, J.; Lugones, L.; Aerts, A.; Kothe, E.; Stajich, J.; De Vries, R.; Record, E.; Levasseur, A.; Baker, S. E.; Bartholomew, K. A.; Coutinho, P. M.; Erdmann, S.; Fowler, T. J.; Gathman, A. C.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B.; Knabe, N.; Kües, U.; Lilly, W. W.; Lindquist, E.; Lucas, S.; Magnuson, J. K.; Piumi, F. O.; Raudaskoski, M.; Salamov, A.; Schmutz, J.; Schwarze, F. W. M. R.; Vankuyk, P. A.; Horton, J. S. (2010). "Genome sequence of the model mushroom Schizophyllum commune". Nature Biotechnology. 28 (9): 957–963. doi:10.1038/nbt.1643. PMID 20622885.

- 1 2 3 4 About Arabidopsis on The Arabidopsis Information Resource page (TAIR)

- ↑ Rushworth, C; et al. (2011). "Boechera, a model system for ecological genomics". Molecular Ecology. 20: 4843–57. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05340.x. PMC 3222738

. PMID 22059452.

. PMID 22059452. - ↑ Brutnell, T; et al. (2010). "Setaria viridis: a model for C4 photosynthesis". Plant Cell. 22: 2537–44. doi:10.1105/tpc.110.075309. PMC 2947182

. PMID 20693355.

. PMID 20693355. - ↑ Jiang, Hui; Barbier, Hugues; Brutnell, Thomas (2013). "Methods for Performing Crosses in Setaria viridis, a New Model System for the Grasses". Journal of Visualized Experiments (80). doi:10.3791/50527. ISSN 1940-087X.

- ↑ Goodin, Michael; David Zaitlin; Rayapati Naidu; Steven Lommel (August 2008). "Nicotiana benthamiana: its history and future as a model for plant-pathogen interactions". Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 21 (8): 1015–1026. doi:10.1094/MPMI-21-8-1015. PMID 18616398.

- ↑ Zhou, S.; Bechner, M. C.; Place, M.; Churas, C. P.; Pape, L.; Leong, S. A.; Runnheim, R.; Forrest, D. K.; Goldstein, S.; Livny, M.; Schwartz, D. C. (2007). "Validation of rice genome sequence by optical mapping". BMC Genomics. 8: 278. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-278. PMC 2048515

. PMID 17697381.

. PMID 17697381. - 1 2 Rensing SA, Lang D, Zimmer AD, et al. (Jan 2008). "The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants". Science. 319 (5859): 64–9. Bibcode:2008Sci...319...64R. doi:10.1126/science.1150646. PMID 18079367.

- ↑ Reski, Ralf (1998). "Physcomitrella and Arabidopsis: the David and Goliath of reverse genetics". Trends in Plant Science. 3: 209–210. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01257-6.

- ↑ "Populus trichocarpa (Western poplar)". Phytozome. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ Srivastava, M.; Simakov, O.; Chapman, J.; Fahey, B.; Gauthier, M. E. A.; Mitros, T.; Richards, G. S.; Conaco, C.; Dacre, M.; Hellsten, U.; Larroux, C.; Putnam, N. H.; Stanke, M.; Adamska, M.; Darling, A.; Degnan, S. M.; Oakley, T. H.; Plachetzki, D. C.; Zhai, Y.; Adamski, M.; Calcino, A.; Cummins, S. F.; Goodstein, D. M.; Harris, C.; Jackson, D. J.; Leys, S. P.; Shu, S.; Woodcroft, B. J.; Vervoort, M.; Kosik, K. S. (2010). "The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity". Nature. 466 (7307): 720–726. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..720S. doi:10.1038/nature09201. PMC 3130542

. PMID 20686567.

. PMID 20686567. - ↑ Holland, L. Z.; Albalat, R.; Azumi, K.; Benito-Gutiérrez, E.; Blow, M. J.; Bronner-Fraser, M.; Brunet, F.; Butts, T.; Candiani, S.; Dishaw, L. J.; Ferrier, D. E. K.; Garcia-Fernàndez, J.; Gibson-Brown, J. J.; Gissi, C.; Godzik, A.; Hallböök, F.; Hirose, D.; Hosomichi, K.; Ikuta, T.; Inoko, H.; Kasahara, M.; Kasamatsu, J.; Kawashima, T.; Kimura, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Kozmik, Z.; Kubokawa, K.; Laudet, V.; Litman, G. W.; McHardy, A. C. (2008). "The amphioxus genome illuminates vertebrate origins and cephalochordate biology". Genome Research. 18 (7): 1100–1111. doi:10.1101/gr.073676.107. PMC 2493399

. PMID 18562680.

. PMID 18562680. - ↑ Riddle, Donald L. (1997). C. elegans II (Full text). Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-532-3.

- ↑ Müller HG (1982). "Sensitivity of Daphnia magna straus against eight chemotherapeutic agents and two dyes". Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 28 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1007/BF01608403. PMID 7066538.

- ↑ Manev H, Dimitrijevic N, Dzitoyeva S (2003). "Techniques: fruit flies as models for neuropharmacological research". Trends Pharmacol Sci. 24 (1): 41–3. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00004-4. PMID 12498730.

- ↑ Chapman, J. A.; Kirkness, E. F.; Simakov, O.; Hampson, S. E.; Mitros, T.; Weinmaier, T.; Rattei, T.; Balasubramanian, P. G.; Borman, J.; Busam, D.; Disbennett, K.; Pfannkoch, C.; Sumin, N.; Sutton, G. G.; Viswanathan, L. D.; Walenz, B.; Goodstein, D. M.; Hellsten, U.; Kawashima, T.; Prochnik, S. E.; Putnam, N. H.; Shu, S.; Blumberg, B.; Dana, C. E.; Gee, L.; Kibler, D. F.; Law, L.; Lindgens, D.; Martinez, D. E.; et al. (2010). "The dynamic genome of Hydra". Nature. 464 (7288): 592–596. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..592C. doi:10.1038/nature08830. PMID 20228792.

- ↑ Ladurner, P; Schärer, L; Salvenmoser, W; Rieger, R (2005). "A new model organism among the lower Bilateria and the use of digital microscopy in taxonomy of meiobenthic Platyhelminthes: Macrostomum lignano, n. sp. (Rhabditophora, Macrostomorpha)". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 43: 114–126. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2005.00299.114-126.

- ↑ Pang, K.; Martindale, M. Q. (2008). "Ctenophores". Current Biology. 18 (24): R1119–R1120. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.004. PMID 19108762.

- ↑ Ryan, J. F.; Pang, K.; Comparative Sequencing Program; Mullikin, J. C.; Martindale, M. Q.; Baxevanis, A. D.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program (2010). "The homeodomain complement of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi suggests that Ctenophora and Porifera diverged prior to the ParaHoxozoa". EvoDevo. 1 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/2041-9139-1-9. PMC 2959044

. PMID 20920347.

. PMID 20920347. - ↑ Darling, J. A.; Reitzel, A. R.; Burton, P. M.; Mazza, M. E.; Ryan, J. F.; Sullivan, J. C.; Finnerty, J. R. (2005). "Rising starlet: the starlet sea anemone,Nematostella vectensis". BioEssays. 27 (2): 211–221. doi:10.1002/bies.20181. PMID 15666346.

- ↑ Putnam, N. H.; Srivastava, M.; Hellsten, U.; Dirks, B.; Chapman, J.; Salamov, A.; Terry, A.; Shapiro, H.; Lindquist, E.; Kapitonov, V. V.; Jurka, J.; Genikhovich, G.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Lucas, S. M.; Steele, R. E.; Finnerty, J. R.; Technau, U.; Martindale, M. Q.; Rokhsar, D. S. (2007). "Sea Anemone Genome Reveals Ancestral Eumetazoan Gene Repertoire and Genomic Organization". Science. 317 (5834): 86–94. Bibcode:2007Sci...317...86P. doi:10.1126/science.1139158. PMID 17615350.

- ↑ The Appendicularia Facility at the Sars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology

- ↑ Wang, X.; Lavrov, D. V. (2006). "Mitochondrial Genome of the Homoscleromorph Oscarella carmela (Porifera, Demospongiae) Reveals Unexpected Complexity in the Common Ancestor of Sponges and Other Animals". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (2): 363–373. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl167. PMID 17090697.

- ↑ Tessmar-Raible, K.; Arendt, D. (2003). "Emerging systems: Between vertebrates and arthropods, the Lophotrochozoa". Current opinion in genetics & development. 13 (4): 331–340. doi:10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00086-8. PMID 12888005.

- ↑ Srivastava, M.; Begovic, E.; Chapman, J.; Putnam, N. H.; Hellsten, U.; Kawashima, T.; Kuo, A.; Mitros, T.; Salamov, A.; Carpenter, M. L.; Signorovitch, A. Y.; Moreno, M. A.; Kamm, K.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Shapiro, H.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Buss, L. W.; Schierwater, B.; Dellaporta, S. L.; Rokhsar, D. S. (2008). "The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans". Nature. 454 (7207): 955–960. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..955S. doi:10.1038/nature07191. PMID 18719581.

- ↑ Reynoldson TB, Thompson SP, Bamsey JL (1991). "A sediment bioassay using the tubificid oligochaete worm Tubifex tubifex". Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 10 (8): 1061–72. doi:10.1002/etc.5620100811.

- ↑ Kolb, E. M., E. L. Rezende, L. Holness, A. Radtke, S. K. Lee, A. Obenaus, and T. Garland, Jr. 2013. Mice selectively bred for high voluntary wheel running have larger midbrains: support for the mosaic model of brain evolution. Journal of Experimental Biology 216:515-523.

- ↑ Wallingford, J., Liu, K., and Zheng, Y. 2010. Current Biology v. 20, p. R263-4

- ↑ Harland, R.M. and Grainger, R.M. 2011. Trends in Genetics v. 27, p 507-15

- ↑ Spitsbergen JM, Kent ML (2003). "The state of the art of the zebrafish model for toxicology and toxicologic pathology research—advantages and current limitations". Toxicol Pathol. 31 (Suppl): 62–87. doi:10.1080/01926230390174959. PMC 1909756

. PMID 12597434.

. PMID 12597434.

This article is issued from Wikipedia - version of the 8/31/2016. The text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike but additional terms may apply for the media files.