Lorca, Spain

| Lorca | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

|

Lorca Castle | |||

| |||

| Motto: Lorca solum gratum, castrum super astra locatum, ensis minans pravis, regni tutissima clavis | |||

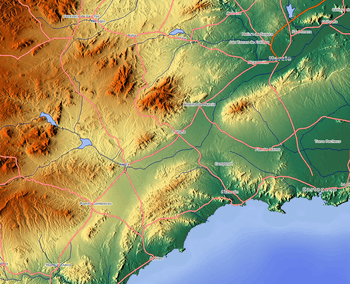

Lorca City location in the Province of Murcia, the municipal area marked around it. | |||

| Coordinates: 37°40′47″N 1°41′40″W / 37.6798°N 1.6944°WCoordinates: 37°40′47″N 1°41′40″W / 37.6798°N 1.6944°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Autonomous community |

| ||

| Province | Murcia | ||

| Comarca | Alto Guadalentín | ||

| Judicial district | Lorca | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Francisco Jódar Alonso (2007) (PP) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 1,676 km2 (647 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 353 m (1,158 ft) | ||

| Population (2010) | |||

| • Total | 92,694 | ||

| • Density | 55/km2 (140/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Lorquino, lorquina | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 30800 | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

Lorca (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈlorka]) is a municipality and city in the autonomous community of Murcia in southeastern Spain, 58 kilometres (36 mi) southwest of the city of Murcia. It had a population of 92,694 in 2010, up from the 2001 census total of 77,477. Lorca is the municipality with the second-largest surface area (after Cáceres) in Spain with 1,675.21 km2 (646.80 sq mi). The city is home to Lorca Castle and the Collegiate church dedicated to St. Patrick.

In the Middle Ages Lorca was the frontier town between Christian and Muslim Spain.[1] Even earlier to that during the Roman period it was ancient Ilura or Heliocroca of the Romans.[2]

The city was seriously damaged by a magnitude 5.1 earthquake on 11 May 2011, killing at least nine people. Due to shallow hypocenter, the earthquake was much more destructive than usual for earthquakes with similar magnitude.

History

Prehistory and Antiquity

Archaeological excavations in the Lorca area have revealed that it has been inhabited continuously since Neolithic times, 5,500 years ago. The earliest permanent settlement is in the Guadalentín River valley, likely because of its presence of water sources, mineral resources, and lying along a natural communication route in Andalusia. On the hillside below the castle and the town archaeological digs have revealed the remains of an important population of the El Argar culture during the Bronze Age.[3]

During the Roman period, a settlement here was called Eliocroca,[4] detailed in the Antonine Itinerary and located right on Via Augusta. Elicroca was important enough to become a bishopric, suffragan of the primatial Metropolitan Archbishopric of Toledo, but it was to fade under Islam.

Feudal and modern era

In 713, the Teodomiro Pact was signed,[5] referring to the place with the name "Lurqa". Under this pact, the population was integrated into an autonomous territory, along with six other cities, governed by Theudimer (Teodomiro). This lasted until his death when a Muslim reorganization of the state occurred, carried out by Abb-al-Rahman II, who turned the territory into a Córdoba dependency. It led to the formation of the Taifa kingdoms,[6] with the Taifa of Lorca as one of these kingdoms, first created in 1042,[7] when Lorca declared its independence from the emirate of Valencia. Its first governor was Ma'n Ibn Sumadih, its power extending from the city to Jaén and Baza. During the Arab period it was known as Lurka and the old part of the town, made up of narrow streets and alley-ways, achieved its present shape under Moorish rule.

The taifa was shortly recreated in 1228, after the fall of the Almoravids, until it conquered by the Taifa of Murcia; in 1244, Fernando III, King of Castilla y León and his son and heir, Prince Alfonso, the future Alfonso X of Castile, conquered Lorca.[8] The main tower of the fortress of Lorca was named Torre Alfonsina in honour of the King. The city continued to grow, as in Arab times, and became the main town in an emerging rich agricultural region, although the border hindered economic development.

Lorca, known as the city of 100 Coat of Arms, is where the Moors and the Visigoths battled for control of the land; initially they both controlled the land up to the border on the north including the city of Larcia while in later years, the Christians and the Moors controlled the city and the land up to the southern border.[9]

During the late Middle Ages, Lorca was a dangerous border town, spearhead of the Christian kingdom of Murcia (belonging to the Spanish crown) against the Moorish Kingdom of Granada. Lorca served as a base for launching raids into enemy territory. The Battle of Los Alporchones, took place here in 1452, during the reign of Juan II of Castile, who ten years earlier had granted the Lorca the title of "ciudad". The Kingdom of Murcia took Granada in 1492.[10]

After the War of Granada and the Muslim threat disappeared, the city changed in appearance, carrying out a series of urban reforms and developing trade. The numerous public works to be carried out attracted labourers from elsewhere, resulting in an increase in the population to 8,000 people. Among the new buildings include the Colegiata de San Patricio, erected in 1553,[11] which is the religious centre of the city, as well as numerous convents of La Merced, Santo Domingo and San Francisco.

In the seventeenth century, Lorca took shape as a modern city, but still had defensive duties due to the Ottoman threat along the coast. This century witnessed the expulsion of the Moors, the plague, which killed half the population, and droughts and locust plagues. Nevertheless, from 1660 a spectacular recovery and development began; amongst the construction of new buildings was the Palacio de Guevara, built in 1694 and a fine example of baroque architecture.[12] The eighteenth century is of vital importance for the city, being one of the regions favoured by the Bourbon reforms. Lorca truly became a modern city, losing its medieval character. The population grew, and urban sprawl began as immigrants settled in the suburbs of San Cristóbal and San José. The defensive wall disappeared, which is indicative of the greater security of the times. The city became a haven for painters, sculptors and engravers.

On 30 April 1802, a great calamity struck the town of Lorca. The walls of a nearby reservoir gave way, flooding the town and destroying many buildings and killing up to 700 people.[4][13] In the nineteenth century, the War of Independence and yellow fever epidemics and recurring droughts brought famine to the region and brought about the emigration of more than twelve thousand people. By 1845 Lorca had become the largest and most populous municipality in Murcia.[4] Trade declined during the first half of the century, although in 1865 it received its first steam engine, the Sewer-Lorca railway opened in 1885 and the Baza-Lorca railway opened in 1890,[14] bringing integration of the region in the domestic market, enabling the movement of mineral deposits and people. Restoration in the late 19th century brought with it a period of prosperity and political calm, the roundabouts of San Vicente, the Teatro y Colón, the Casino Artístico y Literario in 1885, the Teatro Guerra in 1861, and the Plaza de Toros in 1892, etc. were amongst the notable building developments of this time. The 1878 edition of The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information described Lorca (spelled as 'Liorca') thus:

- a town of Spain, province of Murcia, on the Sangonera, 80 kilometres (50 mi) W. of Carthagena. It has an old Moorish castle, and manufactures of silks, soap, dye-stuffs, leather, paper, etc... Near Liorca are important lead mines. Pop. 40,000.[15]

In the early twentieth century, intensive exploitation of mineral deposits of the coastal zone meant a revival of economic life in the region. The Spanish Civil War paradoxically brought about the beginning of population recovery, but in the post-World War II years the population stagnated as a result of emigration. But today the flow has been reversed: the leather, pottery, cement and butcheries make the municipality an agricultural and livestock industrial tone, involving a large percentage of the population. The twentieth century in Lorca has been a technological take-off, with slow and gradual change of social structures, the specialization of the productive sectors, etc.

On October 19, 1973, Lorca and Puerto Lumbreras suffered a terrible flood that took more than 50 lives.[13]

In 2008, Lorca received the annual Honorary Diploma of Europe Awards from the Council of Europe.

On January 29, 2005, an earthquake of 4.6 magnitude on the Richter scale with epicentre in the districts of La Paca (1,068 inhabitants in 2005) and Zarcilla de Ramos (1,077 inhabitants in 2005), caused damage especially in the structure of various buildings, and in Avilés, Coy, Doña Inés, Don Gonzalo, El Pardo, La Canaleja and Zarzadilla de Totana. This was however to be topped by worse.

2011 earthquake

The town was seriously damaged by a magnitude 5.3 earthquake on 11 May 2011, killing at least nine people.[16] The United States Geological Survey (USGS) said the larger earthquake had a preliminary 5.3 magnitude, it was so superficial that the magnitude was like a 7 magnitude normal earthquake, and struck 350 kilometres (220 mi) south-southeast of Madrid at 6:47 p.m. (1647 GMT, 12:47 p.m. EDT). The quake was about 1 km (0.6 mi) deep, and was preceded by the smaller one with a 4.5 magnitude in the same spot.

"The quakes occurred in a seismically active area near a large fault beneath the Mediterranean Sea where the European and African continents brush past each other", USGS seismologist Julie Dutton said. The USGS said it has recorded hundreds of small quakes in the area since 1990.

Lorca Castle, a fortress of medieval origin constructed between the 9th and 15th centuries suffered serious damages to its walls and the Espolón Tower during this earthquake.[17]

Titular see of Elicroca

The Ancient diocese was nominally restored as a titular see in 1969.

It has had the following incumbents, of both the lowest (episcopal) and intermediary (archiepiscopal) ranks :

- Titular Archbishop Paul Clarence Schulte (1970.01.03 – 1984.02.17)

- Titular Bishop Héctor Julio López Hurtado, Salesians (S.D.B.) (1987.12.15 – 1999.10.29)

- Titular Bishop Manuel Neto Quintas, Dehonians (S.C.I.) (2000.06.30 – 2004.04.22)

- Titular Bishop Matthias König (2004.10.14 – ...), Auxiliary Bishop of Paderborn

Geography and climate

The town is situated at an elevation of 370 metres (1,200 ft) in eastern Spain between Granada and Murcia. It was part of the hura[2] of Tidmir in the Muslim period when it became well known for its fertile soil and subsoil, and for its strategic location. It is situated on the southern slopes of the Siera del Cano mountains. The Guadalentín River flows through the town.[2]

The municipality of Lorca is bound by Caravaca de la Cruz and Cehegín to the north, Mula, Aledo, Totana and Mazarrón to the east, Águilas to the south and Pulpí, Puerto Lumbreras, Huércal-Overa, Vélez Rubio and Vélez Blanco to the east. The town of Lorca itself is located 58 kilometres (36 mi) southwest of the city of Murcia and roughly 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of the coastal town of Aguilas.[18] Lorca is connected to Puerto Lumbreras in the southwest by European Route 15 (Route A-7) and the village of Barranco del Prado just to the north. Beyond this the C-3211 road connects it to the city of Caravaca de la Cruz much further to the north.[18] Several towns and villages lie in the municipality, including La Paca, Palm Zarcilla, Avilés, Coy, Doña Inés, Don Gonzalo, El Pardo, La Canaleja and Zarzadilla de Totana.

The municipality is very large at 1,676 km2 (647 sq mi) and has a range of geographical features, extending from the coastline to the mountainous areas of the northwest and northeast of the municipality. Lorca formed around the Guadalentín River (in Arabic "mud river") in an arid valley. In fact, agriculture heavily depends on water transferred from the Tagus river in Central Spain. Irrigation channels were laid out all over the country by the Moors during the Middle Ages. These agricultural plains lie to the south of the main town in the valley, a strip which expands into the western part of the municipality. The area to the north is mountainous; to the northeast is the Parque Natural Sierra Espuna.

Districts of Lorca

Lorca is divided into these districts:

|

|

|---|

Beaches of Lorca

The municipality of Lorca extends to the Mediterranean. There are many beaches in its 8 km (5 mi) litoral stretch of the coast line surrounded by hills with coves with sparse to dense vegetation.[19][20] Some of the popular beaches are: The Calnegre, a sand beach, 1200 m long and 20 m wide, is peaceful with the calm sea;[19][20] Cala Leña, part of the Blana Cove with backdrop of hills covered with good vegetation and facing crystal clear sea water;[20] El Ciscar, a gravel beach surrounded by low hills;[20] El Muerto beach with volcanic black sand and rock faces;[20] La Galera gravel beach in the backdrop of a cove and rock cliffs covered by vegetation;[20] Los Hierros, a gravel beach;[20] Larga beach, a 500 m wide gravel beach; and La Junquera, a small gravely beach with rocky landforms.[19][20]

Climate

Lorca has a warm climate, typical of southeast Spain, with an average annual temperature between 17 and 18 °C. The characteristics of this climate are due to the situation of the municipality, sheltered from the Atlantic storms. Western wet fronts release water when it hit the Betic Cordillera, which separates the Lorca area of depression of the Guadalquivir, which penetrate the winds off the Atlantic. Rainfall usually occur in torrents, falling mostly in a few days of the fall or spring, with very dry summers. The winters are usually mild with mean temperatures below 9 °C. Summers are hot, 36 °C is the common maximum temperature in July and August, although it sometimes reaches more than 40 °C. Due to the size and topographical fluctuation of the municipality, not all areas report the same rainfall and temperatures.

Notable landmarks

Lorca Castle

The Lorca Castle, which overlooks the city of Lorca from a strategic location, and is thus distinctly visible from a distance, was built by the Moorish inhabitants during the 13th century. Its history dates back to the Islamic period when it was built between 8th and 12th centuries; some remnants of which are still seen in the form of water systems in the older part of the castle.[21] The Alfonsí Tower is of a rectangular shape which is built in the castle. The castle has a polygonal floor plan. The tower has three sections. Gothic vaulted ceilings are seen in its three sections.[22] It also has the Espolón Tower. During the final stages of Christian reconquest, the Moors had taken refuge in the castle. Alphonse tower was added to the fort defences when Alfonso X had retaken the city in 1243 provided security to the turrets and crenels of the fort.[9] The castle is now a popular place for holding fiestas and civic functions.[21] The castle is also transformed into a theme park with fine display of "dioramas, actors in costumes and various gadgetry".[23]

Plaza de España

The Plaza de España (Spanish Square) is one of the most emblematic monuments of the city, located in the heart of Lorca's historical centre. Containing the Collegiate San Patricio and the Chambers of the Collegiate members, the Casa del Corregidor and Posito, the granary of the 16th century, amongst others[23] They were built between the 16th and 18th centuries. The Plaza has been declared a Cultural Monument.

Colegiata de San Patricio

The Collegiate Church of San Patricio is a Renaissance-style building situated on the Plaza de España. It was declared a National Historic-Artistic site by decree of January 27, 1941. The Collegiate is the only one in Spain which is under the patronage of St. Patrick. The dedication to the Irish saint, has its origins in the Battle of Los Alporchones, fought on March 17, 1452 (St. Patrick's Day) against people of the city of Granada. The church began construction in 1533 under Pope Clement VII on the spot of the old church of San Jorge. Construction, however, was delayed until 1704.[9] The church features a baroque façade with Renaissance interiors.[23]

Museums

The city has many museums of which the Museo de Arqueologico Municipal maintained by the Plaza de Juan Moreno is popular. There is also an embroidery museum. The city hall has many paintings of battles that were fought in and around Lorca. Paintings of local artists are also on display here.[21]

- Museo Arqueológico

The Archaeological Museum of Lorca is located in the renovated "House of Salazar" which had been built in the early seventeenth century. The museum is a store house of all the archaeological antiquaries found during excavations in several historical areas of Lorca and from other regions in Spain. Limestone statues made in the Lavant area of Lorca decorate the façade. These statues carved are of Mary Natareloo Salazar flanked by figures of two naked female torsos.[23][24] Inside the museum exhibits are in several sections arranged in a sequence. In the lobby and the first section of the museum the exhibits are: Prehistoric Palaeolithic (95000-32000 BC) and chalcolithic period (32,000 to 9000 BC) finds seen in the flint section consist of antiquaries of scrapers, knives and points used by the hunters and gatherers who lived in Black Hill of Jofré and the Correia in Lorca; utensils arrowheads, axes, polished piece, handmade pottery, beads of people who lived in the region of Lorca during the late Neolithic period (3500 BC); the Copper Age (3000 BC) findings of funerary objects found in the caves of the hills in Lorca; stone architecture of the megaliths of the Black Hill in Lorca; the later part of the third millennium idols made from clay, bone and stone from the excavations from the Glorieta de San Vicente (Lorca city), one particular item of display is the triangular plate of stone painted in black with schematic rock art painting and other animal on the shoulder blade; the two columns of Emperor Augustus (8–7 BC) and Emperor Diocletian; and the Roman period mosaics, faces of Venus and the nine females of the period.[23][24][25]

Other monuments

Lorca is studded with ancient monuments built in baroque architecture, Roman villas, palaces, unique works of art.[26] In the central part of the town, La Casa de Guevara is one of the ancient baroque buildings built between 16th and 18th centuries by the Guevara family. Another historical monument is the Iglesia de San Mateo, which has an impressive vaulted interior.[21]

- A Roman Milepost of 10 BC of Emperor Augustus period over which a statue of San Vincente erected in the 15th century is an important landmark on the Columnia Milenaria".[21] It is located on the located on the Calle de la Corredera

- Lorca City Hall, built in the 17th–18th centuries, initially as a prison[21]

- Medieval walls and gate or porch of San Antonio (13th-early 14th centuries) of Arabic origin was the main entrance gate then.[26]

- Monumental complex of Santo Domingo (16th–18th centuries), formed by the namesake church, the Capilla del Rosario and remains of a convent's cloister.

- Iglesia de San Francisco (Lorca) (1561–1735), also known as the temple of San Francisco, is a national monument. It was first built by the Franciscan Order in the middle of the 16th century which was later totally rebuilt in the 17th century. It has many baroque altar pieces made by Ginés López in 1694. In the 18th century, Jerónimo Caballero added two high altarpieces of the transept that are dedicated to the Saint Antonio and to Vera Cruz and to the Blood of Christ. In 1941, the 'Virgin de los Dolores' altarpiece made by José Capuz was added.[27]

- Palace of the counts of San Julián, in Baroque-Neomudéjar style (17th century)

- Huerto Ruano Palace, an urban villa from the 19th century

- Casa del Corregidor, house built in the 18th century

- Pósito de los Panaderos, granary house, built in the 16th century

- Columna Miliaria, Roman structure

- Convento Virgen de las Huertas, Franciscan convent destroyed during a raid in 1653 and rebuilt

- Convento de las Mercedarias (16th century)

- Palacio de Guevara (17th–18th century)

- Antiguo Convento de la Merced

- Antiguo Colegio de la Purísima (18th century), now housing the Conservatorio de Música Narciso Yepes.

- Iglesia del Carmen, 18th-century church

- Iglesia de San Cristóbal (17th–18th century).

- Iglesia de San Diego (17th century).

- Iglesia de San Mateo (18th–19th century).

- Casino Artístico, Andalusian-style building, designed by Manuel Martínez Lorca.

- Teatro Guerra is the oldest theatre in the Murcia Region, inaugurated in 1861.

- Cámara Agrícola (early twentieth century), Art Nouveau building, unusual in this part of the Region of Murcia, designed by Mario Spottorno,

- Puente de Piedra (19th century), bridge

- Puente de la Torta (1910), bridge built in 1910 from concrete

- Plaza de Toros (1892).

Economy

After most of the land and water supplies had been held for centuries by a minority of landowners and by Roman Catholic religious orders, Lorca began a period of sluggish economic growth during the 1960s.

Still today, its economy is largely based on agriculture and stock breeding (pigs and brown cows), although its service industries make it the commercial capital of the surrounding area. The economy of the town is thus dependent largely on export of pork products and textiles.[23] It also has saltpetre, gunpowder, and lead-smelting works. In recent years, Lorca has experienced a population growth because of peasant immigration, mostly coming from Ecuador and Morocco.

Lorca has launched a programme to boost its economy by attracting local, national and international industrial houses to set up base in the city and its precincts by identifying land for allotment to set up industrial parks, Research and Development (R&D) projects. Some of the important recent actions taken by the Lorca City Hall relate to allotment of 52 hectares (130 acres) of land for development through 60 local entrepreneurial projects, 77 hectares (190 acres) to promote investments that would create employment and maximize the Lorca economy, 130 hectares (320 acres) allotted to Turkish investors to develop corporate projects, approval of land programmes for development of Serrata Industrial Park by the Lorca Land and Housing firm (SUVILOR) to develop five parks, setup Health Sciences University Campus for the 2010–2011 under agreements with Israeli firms. Further advantages cited for firms to set up their establishments in Lorca are the approved plans for the allotment of land of 100,000 m2 (1,100,000 sq ft) in Hoya 800,000 m2 (8,600,000 sq ft) in Purias and the identification of land for Zarcilla de Ramos, Zarzadilla de Totana, La Paca and Almendricos for development of industries.[28]

The Region of Murcia, the City Council of Lorca, the Chamber of Commerce of Lorca and the Confederation of Entrepreneurs of the Region of Lorca (Ceclor), as a consortium, have formed the LORCATUR to develop cultural tourism of Lorca. The emphasis is on promoting urban tourist circuits and thematic itineraries. To this end, plans have been taken up to conserve, preserve and restore the built heritage of the city, regenerate urban areas for residents and tourists, and diversify the historical and cultural heritage.[29]

Cultural activity

Cultural activity in Lorca is the Easter celebration, the Holy Week celebration popularly known as the Semana Santa. Semana Santa festival has been popularised since 1855. It is said to be the best festival held anywhere in Spain where two brotherhoods vie with each other to display two colours namely the Azul (blue) and Blanco (white) for the highly competitive festive display of cloaks. Each of the brotherhood in Lorca, on this occasion, carries an image of Virgin Mary – one draped in a blue cloak and another in white cloak with a banner and a museum. Music played on this occasion is of a different rhythm is reverential and vigorously mixing the story of Old Testament and the New Testament. Apart from this annual festival, there are four small museums where exhibits of Semana Santa costumes are on display. These costumes are finely embroidered on silk and depict historical and religious scenes; some of these cloaks are as long as 5 metres (16 ft).[23] Fiesta celebration for La Virgen de Las Huertas is held on 8 September every year.[21]

Education

Centres of educations in Lorca:

|

|

|---|

Healthcare

The public health system that exists in Lorca is managed by the Servicio Murciano de Salud (SMS). In February 2010, Rafael Méndez Hospital was accredited University General Hospital.[30]

.jpg)

Hospitals

- Hospital General Universitario Rafael Méndez[30]

- Hospital Virgen del Alcázar

Health centres

- Centro de Salud Lorca-San Diego

- Centro de Salud Lorca-Sur

- Centro de Salud Lorca-Centro

- Centro de Salud La Paca

- Centro de Salud Sutullena

Clinics

- Consultorio La Torrecilla

- Consultorio Morata

- Consultorio Coy

- Consultorio Zarzadilla de Totana

- Consultorio Las Terreras

- Consultorio Tova-La Parroquia

- Consultorio Campillo

- Consultorio Escucha

- Consultorio Ramonete

- Consultorio Cazalla

- Consultorio Zarcilla de Ramos

- Consultorio Doña Inés

- Consultorio La Campana / Pozo Higuera

- Consultorio Aguaderas

- Consultorio Campo López

- Consultorio Avilés

- Consultorio La Hoya

- Consultorio Marchena

- Consultorio Puente La Pía

- Consultorio Purias

- Consultorio Tercia

- Consultorio Consejero

- Consultorio Almendricos

- Consultorio Torrecilla

Sports

Sports teams

- Athletics

- Atletismo Eliocroca, an athletic club participating at the regional level (cross country, indoor track, outdoor track, route, half marathon, marathon, 100 km).

- Football

- Lorca Deportiva CF (2002–2010)

- Lorca Atlético CF (2010-2012)

- La Hoya Lorca CF, soccer team in the hamlet of La Hoya which is active in Segunda División B.

- Unión Deportiva Zarcilla, football team which is active in the Preferente Autonómica de la Región de Murcia.

- Rugby

- Club Rugby Lorca

- Futsal

- Ciudad de Lorca Fútbol Sala

- Basketball

- Indigo Química, basketball team that plays in the Primera Autonómica.

- Handball

- Club Balonmano Lorca, team that plays in the Segunda División Nacional Masculina y Femenina.

- Asociación Deportiva Eliocroca, team that plays in Segunda División Nacional.

- Vollyeball

- Asociación Deportiva Eliocroca, team which plays in the Liga FEV.

- Swimming

- Club Natación Lorca.

Sports stadiums and venues

- Estadio Francisco Artés Carrasco

- Complejo deportivo Europa

- Ciudad deportiva de La Torrecilla

- Pabellón municipal de San José

- Pabellón municipal San Antonio

- Pabellón municipal de Almendricos

- Pabellón municipal de Las Alamedas

Notable people

- Antoñita Peñuela (1947–1975), musician

- Bartolomé Pérez Casas, composer and conductor (1873–1956).

- Domingo Sastre Salas (1889–1982), banker

- Eliodoro Puche (1885–1964), poet

- Francisco José Barnés y Tomás, historian

- Joaquín Arderíus

- José Luis Munuera (1972–), historian

- José Musso Valiente, writer and politician (1785–1838).

- Juan de Toledo, painter

- Juan Martínez Casuco (1955–), football coach

- Juan Moreno Rocafull (1820–1892), engineer

- Juan Zurano (1948–), retired professional cyclist

- Manuel Muñoz Barberán (1921–2007), painter

- Manuel Pascual Soler (1969–), retired professional cyclist

- Narciso Yepes, guitarist

- Pepín Jiménez (1961–) bullfighter

- Rafael Maroto, military figure

- Rafael Méndez Martínez, (1906–1991), cardiologist

References

- ↑ Damien Simonis (2005). Spain. Lonely Planet. pp. 661–. ISBN 978-1-74059-700-5. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 M. Th. Houtsma (1993). L-Moriscos. BRILL. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Molina, Ángel Luis Molina (2006). Estudios sobre Lorca y su comarca. EDITUM. p. 132. ISBN 978-84-8371-648-9. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845). Encyclopaedia metropolitana: or Universal dictionary of knowledge ... comprising the twofoldadvantage of a philosophical and an alphabetical arrangement, with appropriate engravings. B. Fellowes. p. 344. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Constable, Olivia Remie (1997). Medieval Iberia: readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish sources. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8122-1569-4. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Messier, Ronald A. (19 August 2010). The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad. ABC-CLIO. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-313-38589-6. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Salgado, Felipe Maíllo (1991). Crónica anónima de los Reyes de Taifas. Ediciones AKAL. p. 43. ISBN 978-84-7600-730-3. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Barca, Pedro Calderón de la (1999). El santo rey don Fernando: primera parte. Edition Reichenberger. p. 96. ISBN 978-3-931887-69-8. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 Kelly Lipscomb (15 February 2005). Adventure Guides Spain. Hunter Publishing, Inc. pp. 345–. ISBN 978-1-58843-398-5. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Cobb, Noel (1 September 1992). Archetypal imagination: glimpses of the gods in life and art. SteinerBooks. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-940262-47-8. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Aznar, José Camón; Velázquez, Instituto Diego (1945). La Arquitectura plateresca: por José Camón Aznar.... Instituto Diego Velázquez. p. 147. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Coupe, Alison (2010). Michelin Green Guide Spain. Michelin Apa Publications. p. 498. ISBN 978-1-906261-92-4. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- 1 2 King, Russell; Mas, Paolo de; Mansvelt-Beck, J. (February 2001). Geography, environment and development in the Mediterranean. Sussex Academic Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-898723-90-5. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Ross, , J.M. (editor) (1878). The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information. IV. Edinburgh,Scotland: Thomas C. Jack, Grange Publishing Works. p. 135. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ↑ Tremlett, Giles (12 May 2011). "Spain Shocked by Deadly Earthquake". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ M. Carmen Cruz. "Minuto a minuto: El funeral por las víctimas será esta tarde en el recinto de Santa Quiteria". RTVE.es. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 Google Maps (Map). Google.

- 1 2 3 "Sun and Beach". LOrca Tourism. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Beaches". Sokersultat. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Debbie Jenkins; Marcus Jenkins (June 2006). A Brit's Scrapbook: Going Native in Murc. Cabal Group Limited. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-905430-21-5. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Castillo de Lorca – Lorca Castle". Canoce. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Damien Simonis (1 March 2009). Spain. Lonely Planet. pp. 705–. ISBN 978-1-74179-000-9. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 "Historia de la casa de María Natarello Salazar". museoarqueologicodelorca.com. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "Sala1". museoarqueologicodelorca.com. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- 1 2 "Lorca". Masinternational.com. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "San Francisco Church". lorcaturismo. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "Lorca, internationally recognised industrial location". Investmentmurcia in Spain. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Best practice 24: Protection and rehabilitation of the Lorca, Spain" (pdf). Culture Routes. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 "El Rafael Méndez recibe la acreditación de Hospital General Universitario" (in Spanish). La Verdad. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

Sources and External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lorca. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Lorca, Spain. |

- GigaCatholic on Elicirca bishopric, with titular incumbent biography links

- Ayuntamiento de Lorca

- Cámara de Comercio e Industria de Lorca

- Museo Arqueológico Lorca

- Viva Murcia community info/photos from Lorca town