Mahmud Hotak

| Shah Mahmud Hotak (King Mahmud I) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emir of Afghanistan/Shah of Iran and Afghanistan | |||||

|

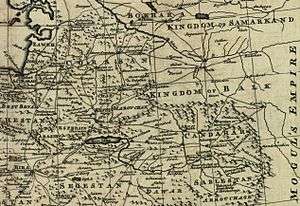

Sketch work of Mir Mahmud Shah | |||||

| Reign | Hotak Empire: 1717–1725 | ||||

| Coronation | 1717 and 1722 | ||||

| Predecessor | Abdul Aziz Hotak | ||||

| Successor | Ashraf Hotak | ||||

| Born | 1697 | ||||

| Died |

April 22, 1725 Isfahan | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Hotak dynasty | ||||

| Father | Mirwais Khan Hotak | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Shāh Mahmūd Hotak, (Pashto, Dari, Urdu, Arabic: شاه محمود هوتک), also known as Shāh Mahmūd Ghiljī (Pashto: شاه محمود غلجي) (lived 1697 – April 22, 1725), was an Afghan ruler of the Hotak dynasty who overthrew the heavily declined Safavid dynasty to briefly become the king of Persia from 1722 until his death in 1725.[1]

He was the eldest son of Mirwais Hotak, the chief of the Ghilji Pashtun tribe of Afghanistan, who had made the Kandahar region independent from Persian rule in 1709.[2] When Mirwais died in 1715, he was succeeded by his brother, Abdul Aziz, but the Ghilji Afghans persuaded Mahmud to seize power for himself and in 1717 he overthrew and killed his uncle.[3]

Mahmud takes the throne of Iran

In 1720, Mahmud and the Ghiljis defeated the rival ethnic Afghan tribe of the Abdalis. However, Mahmud had designs on the Persian empire itself. He had already launched an expedition against Kerman in 1719 and in 1721 he besieged the city again. Failing in this attempt and in another siege on Yazd, in early 1722, Mahmud turned his attention to the shah's capital Isfahan, after first defeating the Persians at the Battle of Gulnabad. Rather than biding his time within the city and resisting a siege in which the small Afghan army was unlikely to succeed, Sultan Husayn marched out to meet Mahmud's force at Golnabad. Here, on March 8, the Persian royal army was thoroughly routed and fled back to Isfahan in disarray. The shah was urged to escape to the provinces to raise more troops but he decided to remain in the capital which was now encircled by the Afghans. Mahmud's siege of Isfahan lasted from March to October, 1722. Lacking artillery, he was forced to resort to a long blockade in the hope of starving the Persians into submission. Sultan Husayn's command during the siege displayed his customary lack of decisiveness and the loyalty of his provincial governors wavered in the face of such incompetence. Starvation and disease finally forced Isfahan into submission (it is estimated that 80,000 of its inhabitants died during the siege). On October 23, Sultan Husayn abdicated and acknowledged Mahmud as the new shah of Persia.[4]

Mahmud's reign as shah

In the very early days of his rule, Mahmud displayed benevolence, treating the captured royal family well and bringing in food supplies to the starving capital. But he was confronted with a rival claimant to the throne when Hosein's son, Tahmasp declared himself shah in November. Mahmud sent an army against Tahmasp's base, Qazvin. Tahmasp escaped and the Afghans took the city but, shocked at the treatment they received at the hands of the conquering army, the population rose up against them in January 1723. The revolt was a success and Mahmud was worried about the reaction when the surviving Afghans returned to Isfahan to bring news of the defeat. Suffering from mental illnesses and fearing a revolt by his subjects, Mahmud invited his Persian ministers and nobles to a meeting under false pretences and had them slaughtered. He also executed up to 3,000 of the Persian royal guards. At the same time the Persian arch rivals, Ottomans, and the Russians took advantage of the chaos in Persia to seize land for themselves, limiting the amount of territory under Mahmud's control.[5]

His failure to impose his rule across Persia made Mahmud depressed and suspicious. He was also concerned about the loyalty of his own men, since many Afghans preferred his cousin Ashraf Khan. In February 1725, believing a rumour that one of Sultan Husayn's sons, Safi Mirza, had escaped, Mahmud ordered the execution of all the other Safavid princes who were in his hands, with the exception of Sultan Husayn himself. When Sultan Husayn tried to stop the massacre, he was wounded, but his action led to Mahmud sparing the lives of two of his young children.[6]

Death

Mahmud began to succumb to insanity as well as physical deterioration. On April 22, 1725, a group of Afghan officers freed Ashraf Khan from the prison where he had been confined by Mahmud and launched a palace revolution which placed Ashraf on the throne. Mahmud died three days later, either from his illness – at it was claimed at the time – or murder by suffocation.

...Thereafter his disorder rapidly increased, until he himself was murdered on April 22 by his cousin Ashraf, who was thereupon proclaimed king. Mír Maḥmúd was at the time of his death only twenty-seven years of age, and is described as "middle-sized and clumsy; his neck was so short that his head seemed to grow to his shoulders; he had a broad face and flat nose, and his beard was thin and of a red colour; his looks were wild and his countenance austere and disagreeable; his eyes, which were blue and a little squinting, were generally downcast, like a man absorbed in deep thought."[7]— Edward G. Browne, 1924

References

- ↑ "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 29. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ↑ Dupree, Mir Wais Hotak (1709–1715)

- ↑ Axworthy p.38

- ↑ Axworthy pp.39–55

- ↑ Axworthy pp.64–65

- ↑ Axworthy pp.65–67

- ↑ "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 31. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

Sources

- Michael Axworthy, The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant Hardcover 348 pages (26 July 2006) Publisher: I.B. Tauris Language: English ISBN 1-85043-706-8

External links

- An outline of the History of Persia during the last two centuries (1722–1922), The Afghan Invasion (1722–1730)

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online – Last Afghan empire

| Mahmud Hotak Born: 1697 Died: 1725 | ||

| Preceded by Abdul Aziz Hotak |

Emir of Afghanistan 1717–1725 |

Succeeded by Ashraf Khan |

| Preceded by Sultan Husayn |

Shah of Persia 1722–1725 |

Succeeded by Ashraf Khan |