Mappila riots

| Mappila Riots (Mappila Outbreaks) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Religion and Peasant Struggles in Malabar | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Hindu jenmi landlords, Government | Mappila Muslims | ||||

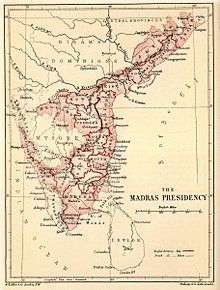

Mappila Riots or Mappila Outbreaks refers to a series of riots by the Mappila (Moplah) Muslims of Malabar, South India in the 19th century and the early 20th century (c.1836–1921) against native Hindus and the state. The Malabar Rebellion of 1921 is often considered as the culmination of Mappila riots.[1] Mappilas committed several atrocities against the Hindus during the outbreak.[2][3] Annie Besant reported that Muslim Mappilas forcibly converted many Hindus and killed or drove away all Hindus who would not apostatise, totalling to one lakh (100,000)[4]

Background

During the Mysorean interlude (1788–1792), the Malabar government reached settlements with the kanakkars in the absence of the Jenmi who had fled persecution to take refuge in the southern state of Travancore. A new system of land revenue was then introduced for the first time in the history of the region and the government share was fixed on the basis of the actual produce from the land.[5]

Historically, the agricultural system in the Malabar was based on a system of hierarchy of privileges, rights and obligations for all the principal social groups in the society. William Logan, the British administrator sometimes referred to as the "Father of Tenancy Legislation" in the Malabar,[6] describes this as a system of 'corporate unity’ or joint proprietorship of each of the principal land right holders:[7][8]

- the Jenmi, mainly consisting of the Nayars and Nambuthiri Brahmins were the highest level of the hierarchy. This class of people were given land grants by the Naduvazhis or the rulers, which was followed in a hereditary nature. The right conveyed by janmam was not a free-hold in the European sense, but an office of dignity. He would instead provide a grant of kanam to the kanakkaran for a fixed share of the produce of the soil. Typically a jenmi would have a large number of Kanakkaran under him.

- the Kanakkaran, mostly belonging the Nayar community. The security and supervision of the land and the distribution of the respective shares was done by the kanakkaran. Like the janmi, the Kanakkaran was also a part-proprietor of the soil to the extent of one-third of the net produce. Each Kanakkaran typically had a number of Verumpattakkaran under him.

- the Verumpattakkaran, generally the Thiyyas and Mappilas were the actual cultivators but were also a part-proprietor. These classes were given a Verum Pattam(Simple Lease) of the land that was typically valid for one year. As per the customary rights, they too were entitled to one-third or an equal share of the net produce.

The net produce of the land was the share left over after providing for the Cherujanmakkar or all the other birthright holders such as the village carpenter, the goldsmith and the agricultural labourers who helped to gather, prepare and store the produce. The system ensured that no Jenmi could evict the tenants under him except for reasons of non-payment of rent. This land tenure system was generally referred to as the janmi-kana-maryada (customary practices).[7][8]

Riot inciters

- Sayyid Sanaulla Makti Thangal

- Sayid Fasal Pookoya Thangal

- Sayyid Alavi Thangal

- Veliyankode Umar Khasi

The Mappila riots at Chembrasseri and Mancheri in 1896 were organised and led by Moideen Kutti Musaliyar, Kappa Kannan Mootha, Pottemmal Unni Mammad and Alingal Aidru.[9] The main leader of this uprising was Moideen Kutti Musaliyar, whose personal grievance against the adhikari of Thoovoor was the cause of the unrest.[9] Over 92 Mappilas were killed during the uprising.[9]

Timeline[10][11]

According to T. L. Strange, the Muslims of Malabar were continuously attempting to incite violence by murdering and attacking Hindus in the region for over a century, the first reported incident being at Panthalur.

- 1836: Kallingal Kunholan from Panthalur, Manjeri kills Cakku Panikkar, a Kanishan (Hindu Jyothishi), and injures another three by stabbing. Kunhlolan was killed two days later by police.

- 1836–1840: Five minor riots, killing or injuring at least six Hindus.

- 1841: An eight-member gang under Tumbamannil Kunhunnyan kills Perumbali Nambudiri, a Brahmin lord, and another Moplah burns Nambudiri's house at Pallippuram, Valluvanad. These people were subsequently killed by the Army and the police.

- Kaitottippadil Moitin Kutti with a seven-member gang kills Tottasseri Tacupanikkar and his assistant. The rioters, hiding in a Moslem mosque, later joined by another three, were killed by the Army and the police after 4 days. A burial of these Moslems faced skirmishes with a 2000 angry Moplah crowd.

- Melemanna Kunhyattan from Eranad with his seven assistants kills Talappil Cakku Nair and another person. Rioters were subsequently killed by Government officers and local people.

- 1843: A gang under Kunnatteri Ali Attan kills the adhikari of Tirurangadi. Later all Moslems, only after a skirmish in which three Government forces were killed, were killed by the Government employees and natives in the presence of the army. Natives sung various heroic songs about this incident in later years.

- Body of a Government employee, brutally murdered, is found.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pg 461, Roland Miller, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol VI , Brill 1988

- ↑ Pg 179–183, Kerala district gazetteers: Volume 4 Kerala (India), A. Sreedhara Menon, Superintendent of Govt. Presses https://books.google.com/books?id=ZF0bAAAAIAAJ

- ↑ Page 622 , Peasant struggles in India, AR Desai, Oxford University Press – 1979

- ↑ Besant, Annie. The Future of Indian Politics: A Contribution To The Understanding Of Present-Day Problems P252. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 1-4286-2605-0.

They murdered and plundered abundantly, and killed or drove away all Hindus who would not apostatize. Somewhere about a lakh of people were driven from their homes with nothing but the clothes they had on, stripped of everything. Malabar has taught us what Islamic rule still means, and we do not want to see another specimen of the Khilafat Raj in India.

- ↑ Pg 53, Kerala Development Report, Government of India Planning Commission, Academic Foundation, 2008

- ↑ Pg 80 Modern Kerala: studies in social and agrarian relations,K. K. N. Kurup ,Mittal Publications, 1988

- 1 2 Pg 17–20, Peasant Struggles, Land Reforms and Social Change: Malabar 1836–1982 By P Radhakrishnan — COOPERJAL

- 1 2 Pg 1- 24, Tenancy legislation in Malabar, 1880–1970: an historical analysis , V. V. Kunhi Krishnan (Ph.D Thesis under Dr. K. K. N. Kurup, Calicut University ), Northern Book Centre, 1993

- 1 2 3 The Quarterly review of historical studies, Volumes 26–27, Institute of Historical Studies., 1986, p. 33

- ↑ Logan, William (2006), Malabar Manual, Mathrubhumi Books, Calicut. ISBN 978-81-8264-046-7

- ↑ Panikkar, K. N., Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar 1836–1921