Marquee Moon

| Marquee Moon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Television | ||||

| Released | February 1977 | |||

| Recorded | September 1976 | |||

| Studio | A & R Recording in New York City | |||

| Genre | Post-punk, rock, art punk | |||

| Length | 45:54 | |||

| Label | Elektra | |||

| Producer | Andy Johns, Tom Verlaine | |||

| Television chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Marquee Moon | ||||

|

||||

Marquee Moon is the 1977 debut studio album by American rock band Television. By 1974, the group had become a prominent act on the New York music scene and generated interest from a number of record labels. Television rehearsed extensively in preparation for Marquee Moon and, after signing to Elektra Records, recorded the album at A & R Recording in September 1976. It was produced by the band's frontman Tom Verlaine and sound engineer Andy Johns.

For Marquee Moon, Verlaine and fellow guitarist Richard Lloyd abandoned contemporary punk rock's power chords in favor of rock and jazz-inspired interplay, melodic lines, and counter-melodies. Verlaine's lyrics combined urban and pastoral imagery, references to lower Manhattan, themes of adolescence, and influences from French poetry. He also used puns and double-entendres to give his songs an impressionistic quality describing the perception of an experience rather than its specific details.

When Marquee Moon was released in February 1977, it received widespread critical acclaim and unexpected commercial success in the United Kingdom, but sold poorly in the United States. The record has since been viewed by critics as one of the greatest albums of all time and a foundational record of alternative rock. Television's innovative post-punk instrumentation on Marquee Moon strongly influenced the indie rock and new wave movements of the 1980s, as well as rock guitarists such as John Frusciante, Will Sergeant, and The Edge.

Background

By the mid 1970s, Television had become a leading act in the New York music scene.[1] They first developed a following from their residency at the lower Manhattan club CBGB, where they helped persuade club manager Hilly Kristal to feature more unconventional musical groups.[2] The band had received interest from labels by late 1974, but chose to wait for an appropriate record deal. They turned down a number of major labels, including Island Records, for whom they had recorded demos with producer Brian Eno.[3] Eno had produced demos of the songs "Prove It", "Friction", "Venus", and "Marquee Moon" in December 1974, but Television frontman Tom Verlaine did not approve of Eno's sound: "He recorded us very cold and brittle, no resonance. We're oriented towards really strong guitar music ... sort of expressionistic."[4]

After founding bassist Richard Hell left in 1975, Television enlisted Fred Smith, whom they found more reliable and rhythmically adept. The band quickly developed a rapport and a musical style that reflected their individual influences: Smith and guitarist Richard Lloyd had a rock and roll background, drummer Billy Ficca was a jazz enthusiast, and Verlaine's tastes varied from the rock group 13th Floor Elevators to jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler.[1] That same year, Television shared a residency at CBGB with singer and poet Patti Smith, who had recommended the band to Arista Records president Clive Davis. Although he had seen them perform, Davis was hesitant to sign them at first. He was persuaded by Smith's boyfriend, Allen Lanier, to let them record demos, which Verlaine said resulted in "a much warmer sound than Eno got". However, Verlaine still wanted to find a label that would allow him to produce Television's debut album himself, even though he had little recording experience.[5]

Recording and production

In August 1976, Television signed a recording deal with Elektra Records, who promised Verlaine he could produce the band's first album with the condition that he would be assisted by a well-known recording engineer.[5] Verlaine, who did not want to be guided in the studio by a famous producer, enlisted engineer Andy Johns based on his work for the Rolling Stones' 1973 album Goats Head Soup.[6] Lloyd was also impressed by Johns, whom he said had produced "some of the great guitar sounds in rock".[1] Johns was credited as the co-producer on Marquee Moon.[5] Elektra did not query Television's studio budget for the recording.[7]

Television recorded Marquee Moon in September 1976 at A & R Recording in New York City. In preparation for the album's recording, Television had rehearsed for four to six hours a day and six to seven days a week. Lloyd said they were "both really roughshod musicians on one hand and desperadoes on the other, with the will to become good".[1] During preparations, the band rejected most of the material they had written over the course of three years.[8] Once they were in the studio, they recorded two new songs for the album—"Guiding Light" and "Torn Curtain"—and older songs such as "Friction", "Venus", and the title track, which had become a standard at their live shows.[9] Verlaine said that, because he had predetermined the structure of the album, only those eight songs and a few others were attempted during the recording sessions.[8] For most of Marquee Moon, Johns recorded Television as they performed live in the studio.[8] A few songs were recorded in one take, including the title track, which Ficca assumed was a rehearsal. Johns suggested the group record another take of the song, but Verlaine told him to "forget it".[10] Verlaine and Lloyd's guitars were recorded and multi-tracked to left and right channels, and the final recordings were left uncompressed and unadorned with studio effects.[11]

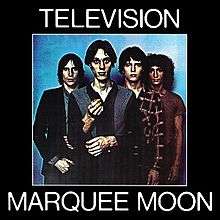

The front cover for Marquee Moon was shot by photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who had previously shot the cover for Patti Smith's 1975 album Horses. His photo situated Verlaine a step in front of the rest of the band, who were captured in a tensed, serious pose. Verlaine held his right hand across his body and extended his slightly clenched left hand forward. When Mapplethorpe gave Television the contact prints, Lloyd took the band's favorite shot to a print shop in Times Square and asked for color photocopies for the group members to mull over. Although the first few copies were oddly colored, Lloyd asked the copy worker to print more "while turning the knobs with his eyes closed".[12] He likened the process to Andy Warhol's screen prints. After he showed it to the group, they chose the altered copy over Mapplethorpe's original photo, which Fred Smith had framed and kept for himself.[13]

Music and lyrics

|

"See No Evil"

The short, hook-driven song featured dual guitar playing by Verlaine and Lloyd, who performed the solo. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

According to Rolling Stone, Marquee Moon was a post-punk album, while Jason Heller from The A.V. Club described it as "elegantly jagged" art punk.[14] Robert Christgau deemed it more of a rock record because of Television's formal and technical abilities as musicians: "It wasn't punk. Its intensity wasn't manic; it didn't come in spurts."[15] Both sides of the album began with three shorter, hook-driven songs, which Stylus Magazine's Evan Chakroff said veered between progressive rock and post-punk styles. The title track and "Torn Curtain" were longer and more jam-oriented.[16] "As peculiar as it sounds, I've always thought that we were a pop band", Verlaine later told Select. "You know, I always thought Marquee Moon was a bunch of cool singles. And then I'd realise, Christ, [the title track] is ten minutes long. With two guitar solos."[17]

Verlaine and Lloyd interplayed their guitars around the rhythm section's drum hits and basslines.[16] Their dual playing drew on 1960s rock and avant-garde jazz styles, abandoning the layered power chords of contemporary punk rock in favor of melodic lines and counter-melodies.[18] Verlaine established the song's rhythmic phrase, against which Lloyd played dissonant melodies.[19] Lloyd had learned to notate his solos by the time they recorded Marquee Moon, allowing him to develop his solo for a song from introduction to variation and resolution.[11] The two traded rhythmic and melodic lines several times on some songs while producing tension.[1] "There weren't many bands where the two guitars played rhythm and melody back and forth, like a jigsaw puzzle", Lloyd said.[19] Most of the solos on Marquee Moon followed a pattern wherein Verlaine ran up a major scale but regressed slightly after each step.[20] On "See No Evil", he soloed through a full octave before playing a blues-influenced riff, and on the title track, he played in a Mixolydian mode and lowered the seventh by half a step.[21] Lloyd opened "Friction" by playing octaves before Verlaine's ringing harmonics and series of descending scales.[22]

_(5720189120).jpg)

Verlaine's lyrics on Marquee Moon combined urban and pastoral imagery.[23] Although it was not a concept album, many of its songs made geographical references to lower Manhattan.[24] According to Bryan Waterman, author of the 33⅓ book on the record, it celebrated stern adolescence in the urban pastoral mode.[25] Its urban nocturne theme was derived from poetic works about Bohemian decadence.[24] According to Spin, the album was about urban mythology; Verlaine brought "a sentimental romanticism to the Bowery, making legends out of the mundane".[26] The lyrics also incorporated maritime imagery, including the paradoxical "nice little boat made out of ocean" in "See No Evil", the waterfront setting in "Elevation", sea metaphors in "Guiding Light", and references to docks, caves, and waves in "Prove It".[27]

"What I love most about the lyrics of Marquee Moon is their evocation of that youthful moment when you're this close to figuring everything out, voicing in very few words a multivalence worthy of that adventure's complexity and confusion — beautifully, profoundly, naively, contradictorily, romantically, kinetically, jokily, cockily, fearfully, drunkenly, goofily, impudently — so nervous and excited you could fly, or is it faint?"

Although Verlaine was against drug use after Television formed, he once had a short-lived phase using psychedelic drugs, to which he makes reference in similes on songs such as "Venus".[28] The vignette-like lyrics follow an ostensibly drug-induced, revelatory experience: "You know it's all like some new kind of drug / my senses are sharp and my hands are like gloves / Broadway looks so medieval, it seems to flap like little pages / I fell sideways laughing, with a friend from many stages."[29] According to Waterman, although psychedelic trips informed the experiences of many artists in lower Manhattan at the time, "Venus" contributed to the impression of Marquee Moon as a transcendental work in the vein of 19th-century Romanticism: "Verlaine is into perception, and sometimes the perception he represents is as intense as a mind-altering substance."[28] Christgau said the lyric about Broadway contributed to how writers have associated the album with the East Village, as it "situates this philosophical action in the downtown night".[15]

The songs on Marquee Moon inspired interpretations from a variety of sources, but Verlaine conceded he did not understand the meaning behind much of his lyrics.[15] He drew on influences from French poetry and wanted to narrate the consciousness or confusion of an experience rather than its specific details. He compared the songs to "a little moment of discovery or releasing something or being in a certain time or place and having a certain understanding of something".[30] Verlaine also used puns and double-entendres in his lyrics, which he said were atmospheric and conveyed the meaning of a song implicitly.[31] "See No Evil" opens with the narrator's flights of fancy and closes with an imperative about limitless possibilities: "Runnin' wild with the one I love / Pull down the future with the one you love".[21] In the refrain to "Venus", the narrator falls into "the arms of Venus de Milo". Verlaine explained his reference to the armless statue as "a term for a state of feeling. They're loving [ubiquitous] arms".[22]

Release and reception

.jpg)

Marquee Moon was released in February 1977 in the United States and on March 4, 1977, in the United Kingdom, where it was an unexpected success and reached number 28 on the country's albums chart.[32] The record's two singles—the title track and "Prove It"—both charted on the UK Top 30.[33] Marquee Moon also received widespread acclaim from critics, and its sales were partly fueled by Nick Kent's rave two-page review of the album for NME.[34] Kent wrote that Television had proven to be ambitious and skilled enough to achieve "new dimensions of sonic overdrive" with an "inspired work of pure genius, a record finely in tune and sublimely arranged with a whole new slant on dynamics". He deemed the album's music vigorous, sophisticated, and innovative at a time when rock is wholly conservative.[35] In a five-star review for Sounds, Vivien Goldman hailed Marquee Moon as "an obvious, unabashed, instant classic", while Peter Gammond of Hi-Fi News & Record Review gave it an "A+" and called it one of the most exciting releases in music, highlighted by Verlaine's steely, Gábor Szabó-like guitar and authentic rock music.[36] In Audio, Jon Tiven wrote that although the vocals and production could have been more amplified, Verlaine's lyrics and guitar "manage to viscerally and intellectually grab the listener".[37] Joan Downs from Time felt the band's sound was distinguished more by the bold playing of Lloyd, who she said had the potential to become a major figure in rock guitar.[38] Christgau gave Marquee Moon an "A+" in The Village Voice and believed Verlaine's "demotic-philosophical" lyrics could have sustained the album alone, as would the guitar playing, which he said was as penetrating and expressive as Eric Clapton or Jerry Garcia "but totally unlike either".[39]

In a negative review, Noel Coppage from Stereo Review was critical of the singing and songwriting, likening Marquee Moon to a stale version of Bruce Springsteen.[40] Nigel Hunter wrote in Gramophone that Verlaine's lyrics and guitar playing were vague and that listeners would need a "strong commitment to this type of music to get much out of it".[41] In Rolling Stone, Ken Tucker said the lyrics generally amounted to non sequiturs, meaningless phrases, and pretentious aphorisms, but were ultimately secondary to the music. Although he found Verlaine's solos potentially formless and boring, Tucker credited him for structuring his songs around chilling riffs and "a new commercial impulse that gives his music its catchy, if slashing, hook".[42] High Fidelity felt the music's "scaring amalgam of rich, brightly colored textures" compensated for Verlaine's nearly unintelligible lyrics.[43]

While holidaying in London after Marquee Moon's completion, Verlaine saw that Television had been put on NME's front cover and called Elektra's press department, who encouraged Television to capitalize on their success there with a tour of the UK. However, the label had already organized for the band to perform on Peter Gabriel's American tour as a supporting act. Television played small theatres and some larger club venues, and received more mainstream exposure, but were not well received by Gabriel's middle-American, progressive rock audiences and found the tour unnerving.[44] In May, the band embarked on a highly successful theatre tour in the UK and were enthusiastically received by audiences. Verlaine said that it was refreshing to perform at large theatres after having played clubs for four years. However, he felt that supporting act Blondie did not suit their show because they were too different artistically, even though both groups had emerged from the music scene at CBGB.[44] Blondie's Chris Stein said that Television were "so competitive" and unaccommodating on the tour and that they did not treat it like a joint effort. He recalled one show where "all our equipment was shoved up at the [Glasgow] Apollo and we had like three feet of room so that [Verlaine] could stand still in this vast space."[45]

At the end of 1977, Marquee Moon was voted the third best album of the year in the Pazz & Jop, an annual poll of American critics nationwide, published in The Village Voice.[46] Christgau, the poll's creator and supervisor, ranked it number one on his own list.[47] Sounds also named it the year's best album, while NME ranked it fifth on its year-end list.[48] Verlaine later said of the overwhelmingly positive response from critics, "There was a certain magic happening, an inexplicable certainty of something, like the momentum of a freight train. That's not egoism but, if you cast a spell, you don't get flummoxed by the results of your spell."[1] By the time of Television's return to the US, however, Elektra had given up on promoting Marquee Moon, which they dismissed as a commercial failure.[7] Marquee Moon sold fewer than 80,000 copies in the US and failed to chart on the Billboard 200.[44] The group was dispirited by their inability to meet commercial expectations, which led to their disbandment in 1978.[44]

Legacy and influence

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Retrospective reviews | |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The Austin Chronicle | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[51] |

| Mojo | |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[53] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[54] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 10/10[57] |

| Uncut | |

According to Tony Fletcher, Marquee Moon was difficult to categorize in 1977 and was hailed as "something entirely original, a new dawn in rock music".[11] Since then, it has been cited by rock critics as one of the greatest records of the American punk rock movement, with Mark Weingarten of Entertainment Weekly calling it the masterpiece of the 1970s New York punk rock scene.[58] According to English writer Clinton Heylin, Marquee Moon marked the end of the New York scene's peak period, while Spin said it was the CBGB era's "best and most enduring record" and ranked it as the sixth greatest album of all time in its April 1989 issue.[59] Q included it in the magazine's 2002 list of the 100 greatest punk records, while writer Colin Larkin ranked it ninth and Mojo ranked it 35th on similar lists.[60] The album has often been voted high in critics polls of the greatest debuts and has also been named one of the greatest records of the 1970s by NME, who ranked it tenth, and Pitchfork, who ranked it third.[61] On September 23, 2003, Marquee Moon was reissued by Rhino Entertainment with several bonus tracks, including the first CD appearance of Television's 1975 debut single "Little Johnny Jewel (Parts 1 & 2)".[62] That same year, it was named the fourth greatest album of all time by NME, while Rolling Stone placed it at number 128 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[63] The record was also ranked 33rd by The Guardian and 25th by Melody Maker on similar lists.[64] According to Acclaimed Music, it is the 23rd most ranked album on critics' all-time lists.[65] It has been viewed as one of the greatest rock albums ever by English radio DJs Marc Riley, who said that "there's been nothing like it before or since", and Mark Radcliffe, who called it "the nearest rock record to a string quartet—everybody's got a part, and it works brilliantly."[66]

Marquee Moon was also one of the most influential records from the 1970s and has been cited by critics as a cornerstone of alternative rock.[67] It heavily influenced the indie rock movement of the 1980s, while post-punk acts appropriated the album's uncluttered production, introspective tone, and meticulously performed instrumentation.[68] Hunter Felt from PopMatters attributed Marquee Moon's influence on post-punk and new wave acts to the precisely syncopated rhythm section of Fred Smith and Billy Ficca. He recommended 2003's "definitive" reissue of the album to listeners of garage rock revival bands, whom he said had modeled themselves after Verlaine's Romantic poetry-inspired lyrics and the "jaded yet somehow impassioned cynicism" of his vocals.[62] According to Sputnikmusic's Adam Downer, Television introduced an unprecedented style of rock and roll on Marquee Moon that inaugurated post-punk music, while The Guardian said it scaled "amazing new heights of sophistication and intensity" as a "gorgeous, ringing beacon of post-punk" despite being released several months before the Sex Pistols' Never Mind the Bollocks (1977).[69] AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine believed the record was innovative for abandoning previous New York punk albums' swing and groove sensibilities in favor of an intellectually stimulating scope that Television achieved instrumentally rather than lyrically. Erlewine claimed "it's impossible to imagine post-punk soundscapes" without Marquee Moon.[49] Fletcher argued that the songs' lack of compression, groove, and unnecessary effects provided "a blueprint for a form of chromatic, rather than rhythmic, music that would later come to be called angular".[11]

In Erlewine's opinion, Marquee Moon was radical and groundbreaking primarily as "a guitar rock album unlike any other".[49] Verlaine and Lloyd's dual playing on the record strongly influenced alternative rock groups such as the Pixies, noise rock acts such as Sonic Youth, and big arena bands like U2.[19] Greg Kot from the Chicago Tribune wrote that Television "created a new template for guitar rock" because of how Verlaine's improvised playing was weaved together with Lloyd's precisely notated solos, particularly on the title track.[70] As a member of U2, Irish guitarist The Edge simulated Television's guitar sound with an effects pedal.[71] He later said he had wanted to "sound like them" and that Marquee Moon's title track had changed his "way of thinking about the guitar".[72] Verlaine's jagged, expressive sound on the album made a great impression on American guitarist John Frusciante when he started developing as a guitarist in his early 20s, as it reminded him that "none of those things that are happening in the physical dimension mean anything, whether it's what kind of guitar you play or how your amp's set up. It's just ideas, you know, emotion."[73] In Rolling Stone, Rob Sheffield called Marquee Moon "one of the all-time classic guitar albums" whose tremulous guitar twang was an inspiration behind bands such as R.E.M. and Joy Division.[56] Joy Division's Stephen Morris cited it as one of his favorite albums, while R.E.M.'s Michael Stipe said his love of Marquee Moon was "second only to [Patti Smith's] Horses".[74] English guitarist Will Sergeant said it was also one of his favorite records and that Verlaine and Lloyd's guitar playing was a major influence on his band Echo & the Bunnymen.[75]

Track listing

All songs written by Tom Verlaine, except where noted.[76]

| Side one | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "See No Evil" | 3:56 |

| 2. | "Venus" | 3:48 |

| 3. | "Friction" | 4:43 |

| 4. | "Marquee Moon" | 9:58 |

| Side two | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 5. | "Elevation" | 5:08 |

| 6. | "Guiding Light" (Verlaine and Richard Lloyd) | 5:36 |

| 7. | "Prove It" | 5:04 |

| 8. | "Torn Curtain" | 7:00 |

| CD reissue bonus tracks | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 9. | "Little Johnny Jewel (Parts 1 & 2)" | 7:09 |

| 10. | "See No Evil" (alternate version) | 4:40 |

| 11. | "Friction" (alternate version) | 4:52 |

| 12. | "Marquee Moon" (alternate version) | 10:54 |

| 13. | Untitled (instrumental) | 3:22 |

- "Marquee Moon", shortened on the original LP, was restored to its complete length of 10:40 on the 2003 remastered CD.[77]

Personnel

Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[76]

Television

- Billy Ficca – drums

- Richard Lloyd – guitar (solo on tracks 1, 4, 5, and 6), vocals

- Fred Smith – bass guitar, vocals

- Tom Verlaine – guitar (solo on tracks 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8), keyboards, lead vocals, production

Additional personnel

- Jim Boyer – assistant engineering

- Greg Calbi – mastering

- Jimmy Douglass – assistant mixing

- Lee Hulko – mastering

- Andy Johns – engineering, mixing, production

- Tony Lane – art direction

- Billy Lobo – back cover artwork

- Robert Mapplethorpe – photography

- Randy Mason – assistant mixing

- John Telfer – management

Charts

| Chart (1977) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| British Albums Chart[9] | 28 |

| Swedish Albums Chart[78] | 23 |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anon. 2007a, p. 378.

- ↑ Tucker 1977; Anon. 2007a, p. 378

- ↑ Heylin 2005, p. 264; Anon. 2007a, p. 378

- 1 2 Hoskyns 2004.

- 1 2 3 Heylin 2005, p. 264.

- ↑ Anon. 2007a, p. 378; Heylin 2005, p. 264

- 1 2 Heylin 2005, p. 271.

- 1 2 3 Heylin 2005, p. 265.

- 1 2 Heylin 2005, p. 269.

- ↑ Heylin 2005, p. 265; Anon.(d) n.d.

- 1 2 3 4 Fletcher 2009, p. 355.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 159.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 160.

- ↑ Anon.(c) n.d.; Heller 2011

- 1 2 3 4 Anon. 2015.

- 1 2 Chakroff 2003.

- ↑ Anon. 1992.

- ↑ Schinder & Schwartz 2008, p. 541; Chakroff 2003

- 1 2 3 Moon 2008, p. 769.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 167.

- 1 2 Waterman 2011, p. 168.

- 1 2 Waterman 2011, p. 174.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 16.

- 1 2 Waterman 2011, p. 162.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 163.

- ↑ Anon. 1989, p. 46.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 166.

- 1 2 Bernhard 2011.

- ↑ Kent 1993, p. 236.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, pp. 17, 162.

- ↑ Waterman 2011, p. 161.

- ↑ Anon. 2007a, p. 378; Anon. 1977b, p. 4; Heylin 2005, p. 269

- ↑ Martin 2003, p. 1060.

- ↑ Anon. 1982, p. 40; Heylin 2005, p. 270.

- ↑ Kent 1993, pp. 234, 235, 239.

- ↑ Goldman 1977, p. 39; Gammond 1977, p. 141.

- ↑ Tiven 1977, p. 90.

- ↑ Downs 1977, p. 82.

- ↑ Christgau 1977.

- ↑ Coppage 1977, p. 94.

- ↑ Hunter 1977, p. 237.

- ↑ Tucker 1977.

- ↑ Anon. 1977a, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 Heylin 2005, p. 270.

- ↑ Heylin 2005, pp. 270–1.

- ↑ Anon. 1978.

- ↑ Christgau 1978.

- ↑ Anon. 1977c, pp. 8–9; Anon.(c) n.d.

- 1 2 3 Erlewine n.d.

- ↑ Chamy 2003.

- ↑ Weingarten 2003, pp. 94–5.

- ↑ Anon. 2003c, pp. 134–6.

- ↑ Galens 1996.

- ↑ Dahlen 2013.

- 1 2 Aizlewood 2003, p. 139.

- 1 2 Sheffield 2003, p. 90.

- ↑ Weisbard & Marks 1995.

- ↑ Brown & Newquist 1997, p. 157; Weingarten 2003, pp. 94–5

- ↑ Heylin 2005, p. 165; Anon. 1989, p. 46

- ↑ Anon. 2002, p. 143; Larkin 1994, p. 236; Anon. 2003b, p. 76

- ↑ Simpson 2013, p. 32; Anon. 1993, p. 19; Pitchfork Staff 2004

- 1 2 Felt 2003.

- ↑ Anon. 2003d, pp. 35–42; Anon. 2003e

- ↑ Anon. 1997, p. A2; Anon. 2000

- ↑ Anon.(a) n.d.

- ↑ Anon. 2001.

- ↑ Martin 2003, p. 1060; Moon 2008, p. 770

- ↑ Woodhouse 2012.

- ↑ Downer 2006; Anon. 2007b

- ↑ Kot 2003.

- ↑ Moon 2008, p. 770.

- ↑ Pattenden 2010.

- ↑ Todd 2012, p. 324.

- ↑ Hewitt 2010; Milner 2004, p. 44

- ↑ Adams 2002, p. 169.

- 1 2 Anon. 2003a.

- ↑ Hegarty & Halliwell 2011, p. 170.

- ↑ Anon.(b) n.d.

Bibliography

- Adams, Chris (2002). Turquoise Days: The Weird World of Echo and the Bunnymen. Soft Skull Press. ISBN 1-887128-89-1.

- Aizlewood, John (November 2003). "Review: Marquee Moon". Q. London (208).

- Anon. (1977). "Pop/Rock". High Fidelity (February).

- Anon. (1977). "Review: Marquee Moon". NME. London (February 9).

- Anon. (1977). "The Sounds 1977 Albums of the Year". Sounds. London (December 24).

- Anon. (1978). "The 1977 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice (January 23). New York. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Anon. (1982). "Record Reviews". Down Beat. Vol. 49 no. December.

- Anon. (April 1989). "The 25 Greatest Albums of All Time". Spin. Vol. 5 no. 1. New York. p. 46. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Anon. (1992). "Review: Marquee Moon". Select. London (September).

- Anon. (1993). "The Greatest Albums Of The '70s". NME. London (September 18).

- Anon. (1997). "100 Best Albums Ever". The Guardian (September 19). London.

- Anon. (2000). "All Time Top 100 Albums". Melody Maker. London.

- Anon. (2001). "Home entertainment: Mark and Lard". The Guardian (March 9). London. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Anon. (2002). "100 Best Punk Albums". Q. London (May).

- Anon. (2003). Marquee Moon (CD reissue booklet). Television. Elektra Records, Rhino Records. R2 73920.

- Anon. (2003). "Top 50 Punk Albums". Mojo. London (March).

- Anon. (2003). "Review: Marquee Moon". Mojo. London (November).

- Anon. (2003). "NME's 100 Best Albums of All Time!". NME. London (March 8).

- Anon. (2003). "128) Marquee Moon". Rolling Stone. New York (November 1). Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Anon. (2007). "Marquee Moon". In Irvin, Jim; McLear, Colin. The Mojo Collection (4th ed.). Canongate Books. ISBN 1-84767-643-X.

- Anon. (November 21, 2007). "1000 albums to hear before you die: Artists beginning with T". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Anon. (2015). "Read an Excerpt From Robert Christgau's Memoir 'Going Into the City'". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- "Television". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- Anon. (n.d.). "swedishcharts.com – Television – Marquee Moon". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on May 1, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- Anon. (n.d.). "Albums and Tracks of the Year for 1977". NME. London. Archived from the original on April 1, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Anon. (n.d.). "Elevation by Television". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Bernhard, Brendan (August 3, 2011). "Five Questions With — Bryan Waterman, Author of 'Marquee Moon'". The Local East Village. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Brown, Pete; Newquist, Harvey P. (1997). Eiche, Jon F., ed. Legends of Rock Guitar: The Essential Reference of Rock's Greatest Guitarists. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-7935-4042-9.

- Chakroff, Evan (August 1, 2003). "Television – Marquee Moon – On Second Thought". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Chamy, Michael (2003). "Review: Marquee Moon, Adventure, Live at the Old Waldorf, San Francisco, 6 / 29 / 78". The Austin Chronicle (December 19). Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- Christgau, Robert (1977). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice (March 21). New York. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Christgau, Robert (1978). "Pazz & Jop 1977: Dean's List". The Village Voice (January 23). New York. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Coppage, Noel (March 1977). "Television: Marquee Moon". Stereo Review. Vol. 38 no. 3.

- Dahlen, Chris (December 9, 2013). "Television / Adventure: Marquee Moon / Adventure". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Downer, Adam (September 29, 2006). "Review: Television – Marquee Moon". Sputnikmusic. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Downs, Joan (1977). "Television: Marquee Moon". Time. Vol. 109 no. April 11. New York. Music section.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (n.d.). "Marquee Moon – Television". AllMusic. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Fletcher, Tony (2009). All Hopped Up and Ready to Go: Music from the Streets of New York 1927–77. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-33483-X.

- Felt, Hunter (September 22, 2003). "Television: Marquee Moon [remastered edition]". PopMatters. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Galens, Dave (1996). "Television". In Graff, Gary. MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0787610372.

- Gammond, Peter (March 1977). "Records of the Month". Hi-Fi News & Record Review. Vol. 22 no. 3.

- Goldman, Vivien (1977). "Review: Marquee Moon". Sounds. London (March 12).

- Hegarty, Paul; Halliwell, Martin (2011). Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock since the 1960s. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 1441114807.

- Heller, Jason (2011). "1977". The A.V. Club (March 9). Chicago. Archived from the original on April 1, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Hewitt, Ben (December 7, 2010). "Bakers Dozen: Joy Division & New Order's Stephen Morris On His Top 13 Albums". The Quietus. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Heylin, Clinton (2005). From the Velvets to the Voidoids: The Birth of American Punk Rock. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-55652-575-3.

- Hoskyns, Barney (2004). "Television: Marquee Moon (Expanded); Adventure (Expanded) (Rhino)". Uncut. London (January).

- Hunter, Nigel (July 1977). "Rock Albums". Gramophone. Vol. 55 no. 650. London.

- Kent, Nick (1993). "I Have Seen the Future ...". In Heylin, Clinton. The Da Capo Book of Rock & Roll Writing. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80920-6.

- Kot, Greg (2003). "Television Marquee Moon Adventure (Elektra/Rhino ...". Chicago Tribune (October 5). Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- Larkin, Colin (1994). Guinness Book of Top 1000 Albums (1st ed.). Gullane Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-85112-786-6.

- Martin, Mike (2003). "Television". In Buckley, Peter. The Rough Guide to Rock (2nd ed.). Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-457-0.

- Milner, Greg (March 2004). "Michael Stipe". Spin. New York. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- Moon, Tom (2008). 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die. Workman Publishing. ISBN 0-7611-3963-X.

- Pattenden, Mike (2010). "The Edge on guitarists, Glasbonbury and musicals". The Times (January 2). London. Retrieved November 20, 2012. (subscription required)

- Pitchfork Staff (June 23, 2004). "Staff Lists: Top 100 Albums of the 1970s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008). Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends who Changed Music Forever. Greenwood Icons. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-33847-7.

- Sheffield, Rob (2003). "Review: Marquee Moon". Rolling Stone. New York (October 16).

- Simpson, Dave (2013). "Television – review". The Guardian (November 17). London. Main section. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- Tiven, Jon (1977). "Record Reviews". Audio (March).

- Todd, David (2012). Feeding Back. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-61374-062-X.

- Tucker, Ken (1977). "Marquee Moon". Rolling Stone. New York (April 7). Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Waterman, Bryan (2011). Television's Marquee Moon. 33⅓. 83. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 1-4411-8605-0.

- Weingarten, Mark (September 26, 2003). "Adventure; Marquee Moon Review". Entertainment Weekly. New York (730).

- Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig, eds. (1995). "Television". Spin Alternative Record Guide. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Woodhouse, Alan (August 3, 2012). "Most Important Albums Of NME's Lifetime – Television, 'Marquee Moon'". NME. London. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

Further reading

- Christgau, Robert (1978). "Television's Principles". The Village Voice (June 19). New York.

- Christgau, Robert (2004). "Television: Marquee Moon/Adventure/Live at the Old Waldorf". Tracks. St Leonards, New South Wales (January).

- Pierre, Jean (2003). "Television – Marquee Moon; Adventure". Tiny Mix Tapes.

External links

- Marquee Moon at Acclaimed Music (list of accolades)

- Marquee Moon at Discogs (list of releases)

- Marquee Moon at Myspace (streamed copy where licensed)