Mathilde, Abbess of Essen

| Mathilde | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbess of Essen | |

| Reign | 973 - 5 November 1011 |

| Predecessor | Ida |

| Successor | Sophia |

| Born | 949 |

| Died |

5 November 1011 Essen |

| House | Ottonian dynasty |

| Father | Liudolf, Duke of Swabia |

| Mother | Ida of Swabia |

| Religion | Catholic |

Mathilde (also Mahthild or Matilda; 949 – 5 November 1011) was Abbess of Essen Abbey from 973 to her death. As granddaughter of Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great she was a member of the Liudolfing dynasty and became one of the most important abbesses in the history of Essen. She was responsible for the abbey, for its buildings, its precious relics, liturgical vessels and manuscripts, its political contacts, and for commissioning translations and overseeing education. In the unreliable list of Essen Abbesses from 1672, she is listed as the second Abbess Mathilde and as a result, she is sometimes called "Mathilde II" to distinguish her from the earlier abbess of the same name, who is meant to have governed Essen Abbey from 907 to 910 but whose existence is disputed.[1]

Sources

Written sources on Mathilde's life and especially on her works are few. Concerning the history of Essen Abbey from 845 to 1150 there exist only some twenty documents in total, not one of which is a contemporary chronicle or biography. While information about Mathilde's life is known on account of her membership in the Liudolfing family, her deeds are only attested by a total of ten references in charters or chronicles from other places. Recently, scholars have attempted to draw conclusions about Mathilde's character from the artworks and building projects which are attributed to her.

Family and youth

Mathilde belonged to the first family of the Holy Roman Empire, as the daughter of Duke Liudolf of Swabia and Ida, a daughter of Duke Hermann I of Swabia, a member of the Conradine dynasty. Her father was the eldest son of Otto I of the Ottonian or Liudolfing dynasty and his Anglo-Saxon wife Eadgyth. Her brother, Otto was Duke of Swabia from 973 and also Duke of Bavaria, from 976 until he died unexpectedly in 982. Her birth was recorded in Regino of Prüm's Chronicon by a continuator before 967, possibly Adalbert, a monk of Trier, under the year 949: "That same year a daughter, Mathilde, was born to the king's son, Liudolf".[2]

Mathilde was probably involved with the Abbey from her youth, perhaps being educated and trained there from 953, or alternatively from 957 (the year of her father's death). Essen Abbey, founded in 845 by Altfrid, Bishop of Hildesheim and Gerswid, who became the first abbess, had been connected with the Liudolfings since its foundation. After a fire in 947, which destroyed all documents about the early history of the Abbey, Abbess Hathwig had had the old rights and privileges of the Abbey confirmed by Emperor Otto I and further obtained immunity and exemption, so that the Abbey achieved Imperial immediacy and was only spiritually subordinate to the Pope. The entrustment of a princess' education to the Abbey would have enhanced its prestige further, putting it on an equal footing with the Abbeys of Gandersheim and Quedlinburg, as a Liudolfing Hauskloster (Dynastic convent). Probably it was already decided at this time that Mathilde would later be abbess; this decision was probably made in 966 at the latest, when Mathilde is first attested in documentary evidence—a record from 1 March 966, in which her grandfather granted a parcel of land (a curtis) to the nuns at her request.[3] This gift probably reflects Mathilde's formal entry into the order.[4]

Mathilde received a comprehensive education appropriate to her status, probably from Abbess Hathwig and Abbess Ida[5] Aside from the Gospels, the books at Essen included the religious authors Prudentius, Boethius, and Alcuin, as well as secular works like Terence and other classical authors which were not only reading material but also the basis of the education of the girls entrusted to the Abbey.[6] Through these, Mathilde was well prepared for her office. On the reported inscription of the Marsus Shrine it was stated that she could write in Latin and had also mastered Greek to an extent.

Abbess

Mathilde is first named in a source as Abbess of Essen in 973. This document, issued in Aachen on the 23 July 973 reads:[7]

Otto confirmed to the Essen cloister founded by Bishop Altfried, at the request of Abbess Mathilde and in accordance with the advice of the Archbishop Gero and of Otto his kinsman, just as his predecessors: the free choice of abbess, the donations made by earlier lords and other believers, which were listed by name and the property titles which were lost in the cloister fire, and immunity with the right of the abbess to choose a Vogt to administer justice to the people of the cloister when necessary.

The individuals mentioned in this document are Emperor Otto II, and Gero, the important Bishop of Cologne, to whom the Gero Cross owes its name, while "Otto his kinsman" is Mathilde's brother Otto of Swabia. At this point Mathilde was about 24 years old and thus still under the age at which she could technically receive appointment as abbess.

Mathilde was not an abbess who remained secluded in monastic silence. In addition to travel to Aachen in 973, further trips are recorded: to Aschaffenburg in 982, Heiligenstadt in 990 and 997, Dortmund, and Thorr. It is also assumed that she made a trip to Mainz in 986 for her mother's funeral. In addition, she must have maintained a wide spanning network of contacts; art historical parallels indicate contacts in Hildesheim, Trier, and Cologne, while she acquired relics in Koblenz (St Florinus) and Lyons (St Marsus) and transferred land which had belonged to her mother to Einsiedeln Abbey. There she was recorded as a benefactrix and honoured with the title of ducissa (duchess).[8] She corresponded with the Anglo-Saxon Earl Æthelweard, who translated his chronicle into Latin for her (see below). All these activities of Mathilde functioned, above all, to fulfill the interests of her abbey and to ensure the salvation of her deceased family members. This is especially clear in Æthelweard's Chronicle, in which Æthelweard places particularly emphasis on genealogical relationships, noting in the introduction the common descent of Mathilde and himself from King Æthelwulf of Wessex.[9]

Politician

Essen Abbey was an Imperial abbey like Gandersheim and Quedlinburg and the abbess herself came from the Imperial family. Documentation that she took part in the Italian campaign of her young uncle, Otto II, like her eponymous aunt Matilda, Abbess of Quedlinburg, and her younger brother Otto is lacking. However, her involvement in the burial of her brother in the Abbey church of St Peter and Alexander, which had been founded in Aschaffenburg by her father, after he died in Italy in 982, is documented by an entry in a manuscript at St Peter and Alexander. Her uncle Otto II died in Rome a year later.

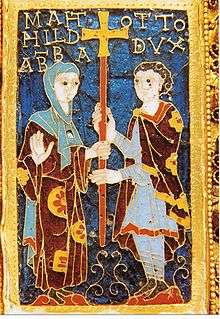

Otto II's fatal Italian campaign was a turning point in Mathilde's life. As a result of her brother's death, she became the last member of the Swabian branch of the Liudolfing dynasty and therefore the manager of the possessions of the family.[10] Furthermore, the death of her brother and her uncle Otto II on the campaign catapulted her to the centre of Imperial politics, since her cousin Henry the Wrangler, who had lost the Duchy of Bavaria to Mathilde's brother Otto in 976, kidnapped Otto II's heir, the three-year-old Otto III and claimed the regency. Based on the absence of written evidence of Mathilde's activities at this time it was traditionally assumed that Mathilde had no further political influence after the death of her brother. However, These argued that Mathilde certainly did not enjoy Henry the Wrangler's favour and that Henry's victory would have led to a reduction of Imperial patronage to Essen Abbey and therefore a loss of significance for the Abbey. In the donor portrait of the Cross of Otto and Mathilde, created at Mathilde's order possibly during the crisis, Mathilde is depicted standing upright in the costume of a member of the high nobility, contrary to the usual depiction of the donor as a humble worshipper in monastic costume. Therefore, it has been concluded that Mathilde maintained a pronounced self-confidence and was not willing to stay out of secular matters.[11] Mathilde was also guardian of Otto III's sister Matilda at this time. What exactly Mathilde did in this crisis, in which Otto II's widow Theophanu along with Otto I's widow Adelaide of Italy contested the regency with Henry, is not documented. However, the Golden Madonna came to Essen at this time and it could be interpreted as symbolic of Theophanu's right to care for her son Otto III as Mary cared for her own royal son. In 993, when Otto III visited Essen Abbey, he donated the crown with which he was crowned king as a small child in 983. Otto III also donated a battle-worn sword of Damascus steel with a golden sheath, which served as the ceremonial sword of the Abbesses of Essen and in later tradition was claimed to be the execution sword of the martyred Saints Cosmas and Damian. These gifts of royal insignia, for which there are no contemporary parallels at all at other abbeys, encourage the conclusion that Otto was offering his thanks for Mathilde's help in securing his rule. Mathilde had already met the king in 990. On 20 January of that year in Heilingstadt, Otto renewed a donation of Mathilde's mother at her request and with the advice of the Archchancellor Willigis:[12]

At the proposal of Archbishop Willigis and the request of Abbess Mathilde of Essen, Otto renewed the donation of Rhöda which Ida, a distinguished woman, gave to the canonical order of Hilwart's house at Essen

Visits to Essen by Otto III are assumed in 984 and 986, since in both years, there is a gap of some time between attestations of Otto in Dortmund and Duisburg. In April 997 Mathilde travelled to a Hoftag of Otto at Dortmund, where Otto transferred royal property on the Upper Leine to Essen Abbey. It is possible that she spent some time in Otto's court in this year, since she is mentioned as a witness in a document from Thorr in September. Otto also facilitated the donation of relics, especially those of Marsus, to Essen Abbey which became the centre of commemoration of his father in Saxony.[13]

Patron of the arts

Hints of Mathilde's personality emerge only from the surviving remains of her artistic patronage. Taking over the management of the assets of her family, particularly the inheritance of her grandmother Eadgyth and her mother Ida (after 986), placed Mathilde in the position to freely use a considerable fortune. With this fortune Mathilde financed artistic treasures to preserve the memory of her relatives and herself. The chronicle which the Anglo-Saxon historian Æthelweard dedicated to Mathilde served as a memorial for her Anglo-Saxon ancestors through Eadgyth. Æthelweard records that it was at her request that he translated (or had translated) his Chronicon de Rebus Anglicis a version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, including material not found in surviving Old English versions, into Latin. This occurred after 975 and probably before 983.[14] The text survives only in a single copy, now in the British Library,[15] which was badly damaged in the Cotton Library fire in 1731, so that later portions are lost. Mathilde probably repaid Æthelweard with a copy of Vegetius' work De Re Militari which was written in Essen's scriptorium and has long been in England.[16]

But Mathilde is especially known for the works of goldsmithery which were made at her order or acquired for Essen Abbey by her. These include two jewelled crosses which she had made for the abbey, now in the Essen Cathedral Treasury, both important works of Ottonian art: both have donor portraits of her in enamel, in the first, the Cross of Otto and Mathilde, she appears together with her brother Otto (died 982), and in the "second Mathilde cross" she is represented with the Virgin and Child. A similar third Essen cross with large enamels may well also have been a product of her patronage.[17] The earliest surviving decorative sword and the Golden Madonna of Essen, an exceptionally rare statue covered with sheet gold, both date to her abbacy at Essen, and were either commissioned by her or given to her.[18] A large seven-armed gilt-bronze candelabrum, over seven feet high, records Mathilde's commissioning of it in an inscription.[19] All these works remain at Essen.

Mathilde had an expensive chasse made as a memorial of Empress Theophanu for her son Otto II, would have exceeded the splendour of the treasures of the churches of Cologne on its own.[20] It is attributed to Mathilde because of the reported inscription in dactylic hexameter:

Hoc opus eximium gemmis auroque decorum

Mechtildis vovit, quae Theophanum quoque solvit

Abbatissa bona Mechthildis chrisea dona

Regi dans regum, quae rex deposcit in aevum

Spiritus ottonis pascit caelestibus orisEnglish:

This work, rich in gems and gold of beauty

Mathilde ordered, she who freed Theophanu also.

Good Abbess Mathilde giving golden gifts

to the King of kings, which the king demands for eternity,

feeds the Spirit of Otto in the celestial realms

This collection of relics was later known as the Shrine of Marsus after the most important relic stored in it and was the oldest reliquary chasse in the Empire, precursor to the Rheinish reliquary shrines, of which the best known is the Shrine of the Three Kings in Cologne.[21] The Shrine of Marsus was made of gold and decorated with numerous gilt enamel plaques and gems. The largest of these was an image of Emperor Otto II on the backside of the shrine, which based on a depiction of the shrine in an altarpiece depicted Otto in worship and also acted as a memorial. This first large chasse was destroyed as a result of the stupidity of the Abbey servants responsible for evacuation in 1794, when it was taken to be safe from French plunder. The remains were melted down, and a masterpiece of Ottonian art was irreparably lost.

Mathilde is probably also the donor of the more than life size Triumphal cross in the Aschaffenburg Abbey church of St Peter and Alexander, whose paintwork corresponds to the edging decoration of the Cross of Otto and Mathilde. Since Mathilde's brother Otto was buried in this church, this cross was probably part of his memorial.[22]

Mathilde's building programme

Georg Humann, the first art historian who concerned himself with the buildings and artefacts of Essen Abbey had ascribed the westwerk of Essen Minster to Mathilde by means of stylistic comparisons. Subsequent research has affirmed this understanding; Mathilde is seen as the initiator of the westwerk, which since the excavation of a predecessor building in 1955 by Zimmerman had been considered mostly the work of Abbess Theophanu who reigned 1039-1058.[23] Mathilde is therefore also responsible for the earliest plumbing yet found at Essen, a lead pipe which ran transversly under the Weswerk and throughout the Abbey buildings. Such water pipes were uncommon in the Early Middle Ages and only found in opulent buildings; they therefore indicate the prestige of the builder.

The question of whether this was Mathilde or Theophanu was uncontentious, but a change in building style did occur in this time. Had the Essen westwork—a masterpiece of Ottonian construction—first been built under Theophanu, it would have been built later than one of the masterpieces of the succeeding Romanesque style, St Maria im Kapitol in Cologne (which was built by Theophanu's sister Ida). On the other hand, Theophanu is praised for rebuilding the Essen cloister in the Brauweiler family chronicle of the Ezzonid family (of which Theophanu was a member). The work carried out by Zimmerman supported the latter position, which also held that the predecessor building was completed in 965. In this case, Mathilde would have actually had a new building constructed, only for it to be replaced by the modern Minster.[24]

Lange drew attention to symbolism of the building programme which he recognised in the plan of the westwerk. The Octagon is clearly influenced by Aachen Cathedral and Otto III's policy of Imperial restoration. In the time of Theophanu, this system no longer made sense.[25] This view interprets the part of the Brauweiler Chronicle which says that Theophanu had the Abbey buildings renewed, as just a reference to a spiritual restoration of the community by Theophanu. A secure date for the construction of the westwerk of the earlier building does not exist. The proponents of an early dating of the current building therefore also date the preceding building earlier, pointing to the fact that westwerks were usually created immediately after the achievement of immunity, which Essen probably achieved before 920. In that case the earlier Westwerk would have no longer been a new building when construction began under Mathilde.

It is also possible that both abbesses did building work on Essen Minster since there are signs of a long term building project. In this case the reference in the Brauweiler Chronicle would be interpreted to indicate that Theophanu completed a construction project begun by Mathilde.

Theories on the foundation of the Rellinghausen Abbey

Mathilde has also been identified as the founder of the Abbey of Rellinghausen (now a suburb of Essen), since a grave inscription was supposed to have been found in its Abbey church, according to which she founded the Abbey in 998 and was buried there at her request. Her foundation of Rellinghausen is challenged in newer research, since direct testimony is lacking and the grave inscription was identified as an early modern forgery.[26] However, Rellinghausen Abbey is mentioned in Abbess Theophanu's will of 1058 as the foundation of one of her predecessors. The abbess who reigned between Mathilde and Theophanu, Sophia, a sister of Otto III, who was simultaneously Abbess of Gandersheim, is unlikely to have been the founder of Rellinghausen. Sophia resided predominantly at Gandersheim and left behind only small traces at Essen. The sister-abbey of Gandersheim was probably founded in the 940s and Quedlinburg's sister abbey was definitely founded in 986 and it seems unlikely that Essen would have founded a sister abbey before these richer and more important Abbeys, so the foundation of Rellinghausen before Mathilde began her tenure in 971 can probably be excluded. Thus, the foundation of Rellinghausen by Mathilde can clearly no longer be considered proven, but it is not impossible.

Mathilde and her namesake

The abbess of Essen is not to be confused with her younger cousin Matilda of Germany, Countess Palatine of Lotharingia (979–1025), daughter of Otto II, who was entrusted to her cousin's care in the abbey at a very young age. It was intended that Matilda would stay in the Abbey and become an abbess like her cousin and older sisters Adelheid I, Abbess of Quedlinburg, and Sophia I, Abbess of Gandersheim, but she was ultimately married to Ezzo, Count Palatine of Lotharingia around 1000. This was despite strenuous objections by the Abbess Mathilde, such that Ezzo had to go to Essen to extract his bride. The marriage seems to have been designed to settle a dispute over Ottonian lands claimed by Ezzo, but was apparently very happy. It produced ten children including Theophanu, later another Abbess of Essen (died 1056).

Last years, death, and burial

The death of Otto III, who had strongly supported Essen Abbey, was probably a watershed for Mathilde. Otto's successor was the Henry II, the son of Henry the Wrangler. Henry did confirm the privileges of Essen Abbey in a document of 1003, but disputes probably arose over Mathilde's personal possessions inherited from her brother and mother. None of Mathilde's donations to the Essen Treasury can be dated to the period after 1002. There are clear signs that construction stopped on the westwerk, so it is assumed that Mathilde's income from the Swabian-Ottonian line had suddenly been reduced with the coronation of Henry II.[27] In that case, Henry had prematurely appropriated the inheritance, which would have come to him anyway after the death of Mathilde since he was the last member of the Ottonian dynasty. Therefore, Mathilde had probably been involved in the opposition to his succession, which had been especially strong in the Lower Rhine. The leaders of this opposition were Heribert, Archbishop of Cologne, and particularly Ezzo, Count Palatine of Lotharingia, the husband of Otto III's sister Matilda who had been educated in Essen, who probably made claims to the throne on behalf of his children. Ezzo was in a similar situation to Mathilde, since he claimed that the dynastic property of the Ottonian line fell to him on account of his marriage to a sister of the childless Otto III, a proposition which Henry II refused to accept. This succession dispute lasted until 1011, when Henry must have given in. If Mathilde also got her property back, it was by then too late to resume the projects she had begun. A penny of Henry II (HENRICVS REX) found in modern Poland in 1996, which names Mathilde on the reverse (+MATHILD ABBATISSA ASNI DENSIS), indicates that Mathilde found such high favour with Henry II, at least for a little while, that she was named on his money. This coinage might therefore have been created after 1002, perhaps a commemorative series created after Mathilde's death to effect a reconciliation between Henry II and the Rheinish opposition led by the Ezzonids.[28]

Mathilde, under whom Essen Abbey had enjoyed a great period of prosperity, died at Essen on 5 November 1011. In the Annals of Quedlinburg Abbey, a foundation of Mathilde's grandfather Otto the Great it is stated:

- Abstulit [sc. mors] et de regali stemmate gemmam Machtildam abbatissam, Ludolfi filiam.

- ([death] took Abbess Mathilde, Luidolf's daughter, the gem of the royal line).[29]

Since the grave of Mathilde in Rellinghausen has been determined to be a fake, she was probably buried in a prominent place in the crypt of Essen Minster. During excavations in the church in 1952, a grave was discovered in the crypt in front of the high altar, a position in which important people were often buried. At the time this grave was identified as that of the Abbess Suanhild who died in 1085 and was known to have been buried in front of this altar. However, according to late Medieval records, the members of the Abbey thought that two Abbesses were buried there, of which one was not identified by name. Therefore, it has subsequently been suggested that Suanhild was buried in a high grave on top of the grave of Mathilde and that the location of Mathilde's burial place fell into obscurity as a result.[30]

Successors and memory

Mathilde's direct successor was Sophia, a daughter of Otto II. She was probably a substitute for her sister Matilda who had been educated in Essen but had then been married to Ezzo and therefore could not be abbess. Her appointment was probably also a political decision, since Sophia had been educated in Gandersheim by the sister of Henry the Wrangler and was a partisan of Henry II, so she assured Henry of political control over Essen Abbey and against the Rheinish opposition.[31] Sophia preferred Gandersheim Abbey, which she had been Abbess of since 1002. As a result, the projects begun by Mathilde remained unfinished at this time.

Sophia's successor, Theophanu, was the daughter of Ezzo and the Matilda who had been Mathilde's intended successor. She fulfilled Mathilde's plans. The so-called Cross of Mathilde in the Essen cathedral treasury depicts Mathilde in monastic costume, at the feet of the enthroned Mary, was a donation of Theophanu in memory of Mathilde. Theophanu's renovation of the crypt of the abbey church moved Mathilde's grave to the centre of the crypt and surrounded it with the relics of saints, which she has especially treasured. The erection of this memorial complex sought Mathilde's liturgical advancement.[32]

Mathilde's memory became celebrated especially in Essen, with four masses and the lighting of the grave with twelve candles. In the Liber Ordinarius, a manuscript of Essen created around 1300, Mathilde is called Mater ecclesiae nostrae (Mother of our church). Abbess Mathilde was depictedOn the lost west windows of the Minster, which were donated by a member of the Essen order, Mechthild von Hardenburg, between 1275 and 1297. There she was called:

- Mechthildis abbatissa huius conventus olim mater pia

- Abbess Mechthildis, once pious mother of this convent.[33]

Notes

- ↑ Tobias Nüssel, Überlegungen zu den Essener Äbtissinnen zwischen Wicburg und Mathilde, in Das Münster am Hellweg 63, 2010, pp. 20–22.

- ↑ Van Houts, 60 n. 30: Eodem anno Liudolfo filio regis Mahthilidis filia nascitur.

- ↑ Van Houts, 60 n. 30: donavimus curtem quae sita est in villa Ericaeli, quam olim ob petitionem filii nostri Liutolfi filiae suae Mahthildi in proprium concessimus ("[to Essen] we have given a curtis that is situated in the village of Ericaeli, which on account of the petition of Mathilde, daughter of our son Liudolf, we have ceded"); the document is transcribed in full by Theodor Sickel, Urkunden Konrad I. Heinrich I. und Otto I., no. 325 "Otto schenkt den Nonnen zu Essen den Hof Erenzell" p 439f; Erenzell is better known as Eherenzell: John W. Bernhardt observes of this document "With this charter, Otto granted the canonesses at Essen a court at Ehrenzell that he had formerly given to his granddaughter Mathilda" (Bernhardt, Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany, 2002, p. 115); The history of the hof at Ehrenzell is given in Wilhelm Grevel, Der Essendische Oberhof Ehrenzell (Philipsenburg), 1881.

- ↑ Bodarwé, Sanctimoniales literattae, p. 54.

- ↑ Tobias Nüssel, "Überlegungen zu den Essener Äbtissinnen zwischen Wicburg und Mathilde," in Das Münster am Hellweg 63, 2010, p. 30.

- ↑ For the Essen book catalogue: Bodarwé, Sanctimoniales litteratae, pp. 246–282

- ↑ Document No. 40 in: This series of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica is not recognised

- ↑ Röckelein, Der Kult des heiligen Florinus in Essen, p. 84.

- ↑ Bodarwé, Sanctimoniales litteratae, p. 279-280; van Houts, "Woman and the writing of history in the early Middle Ages, the case of Abbess Mathilda of Essen and Aethelweard" in Early Medieval Europe 1992, 56ff.

- ↑ Beuckers, Das Otto-Mathilden-Kreuz im Essener Münsterschatz, p. 54.

- ↑ Körntgen, Zwischen Herrschern und Heiligem, p. 20; Beuckers, Das Otto-Mathilden-Kreuz im Essener Münsterschatz, p. 63.

- ↑ Document No. 59 in: This series of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica is not recognised

- ↑ Beuckers, Marsusschrein, S. 47-48.

- ↑ Miller, Sean, "Æthelweard" in The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge, 2001

- ↑ Chronicon de Rebus Anglicis, BL Cotton MS, Otho A.x

- ↑ Bodarwé, Sanctimoniales litteratae, S. 441.

- ↑ Lasko, 99–104.

- ↑ Lasko, 104-105, 125; Van Houts, 60–61.

- ↑ Lasko, 115-117

- ↑ Beuckers, Marsusschrein, p. 1f. referencing Aegidius Gelenius, who described the chasse in 1639.

- ↑ Beuckers, Marsusschrein, p. 121.

- ↑ Beuckers, Das Otto-Mathilden-Kreuz im Essener Münsterschatz, p. 57.

- ↑ Lange, Westbau, pp.1ff.

- ↑ Zimmermann: Das Münster zu Essen. Die Kunstdenkmäler des Rheinlands; Supplement 3, p. 52.

- ↑ Lange, Westbau, p. 72.

- ↑ Lange, Die Krypta der Essener Stiftskirche, p. 171; Sonja Hermann, Die Essener Inschriften, pp. 69-70 holds that the inscription is genuine, but refers to a different individual.

- ↑ Beuckers, Das Otto-Mathilden-Kreuz im Essener Münsterschatz, p. 55.

- ↑ Heinz Josef Kramer, "Ein Mathilden-Denar aus Masowien - Chronik einer Entdeckung" in Das Münster am Hellweg 65, 2012, pp. 26-33.

- ↑ edited: Martina Giese (ed.): Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi 72: Die Annales Quedlinburgenses. Hanover, 2004, pp. 531 Z. 9-10. (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 531 Z. 9-10. digitalised)

- ↑ Lange, Die Krypta der Essener Stiftskirche, pp. 172ff.

- ↑ Beuckers, Marsusschrein, p. 46.

- ↑ Lange, Die Krypta der Essener Stiftskirche, p. 177.

- ↑ Sonja Hermann: Die Essener Inschriften S. 74-75 Nr. 45.

Literature

- van Houts, Elisabeth. "Women and the Writing of History in the Early Middle Ages: The Case of Abbess Matilda of Essen and Aethelweard". Early Medieval Europe, 1 (1992): 53–68.

- Klaus Gereon Beuckers: Das Otto-Mathildenkreuz im Essener Münsterschatz. Überlegungen zu Charakter und Funktion des Stifterbildes. In: Herrschaft, Liturgie und Raum – Studien zur mittelalterlichen Geschichte des Frauenstifts Essen. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2002, ISBN 3-89861-133-7, pp. 51–80. (German)

- Birgitta Falk, Andrea von Hülsen-Esch (ed.): Mathilde - Glanzzeit des Essner Frauenstifts. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0584-9. (German)

- Edgar Freise (1990), "Mathilde II.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 16, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 374–375; (full text online)

- Lasko, Peter, Ars Sacra, 800-1200, Yale University Press, 1995 (2nd edn.) ISBN 978-0300060485