Maxfield Parrish

| Maxfield Parrish | |

|---|---|

Maxfield Parrish in 1896 | |

| Born |

Frederick Parrish July 25, 1870 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

March 30, 1966 (aged 95) Plainfield, New Hampshire |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Haverford College |

| Known for | Painter, illustrator |

| Spouse(s) | Lydia Austen |

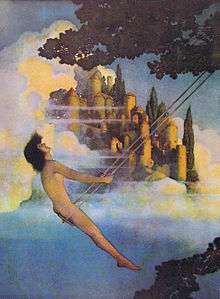

Maxfield Parrish (July 25, 1870 – March 30, 1966) was an American painter and illustrator active in the first half of the 20th century. He is known for his distinctive saturated hues and idealized neo-classical imagery.

Early life and education

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he was the son of painter and etcher Stephen Parrish.[1] His mother was Elizabeth Bancroft. [2]He began drawing for his own amusement as a child. He was raised in a Quaker society.[1]:110 His given name was Frederick Parrish, but he later adopted the maiden name of his paternal grandmother, Maxfield, as his middle name, and later as his professional name.[3] Young Parrish's parents encouraged his talent. In 1884, his parents took Parrish to Europe. He toured England, Italy, and France. Parrish was exposed to architecture and the paintings from the old masters. They returned in 1886.[2]:110 During their travels, however, Parrish studied at the Paris school of a Dr. Kornemann.[3]

He attended the Haverford School, Haverford College in 1888. He studied architecture there for two years.[1] From 1892 to 1895, he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to further his education in art. He studied under artists Robert Vonnoh and Thomas Pollock Anshutz.[2]:110 After graduating from the program, Parrish went to Annisquam, Massachusetts where he and his father shared a painting studio. A year later, he attended the Drexel Institute of Art, Science & Industry with his father's encouragement.[1]

Career

Parrish entered into an artistic career that lasted for more than half a century, and which helped shape the Golden Age of illustration and American visual arts.[4] During his career, he produced almost 900 pieces of art including calendars, greeting cards, and magazine covers.[5] Parrish's early works were mostly in black and white.[6]

In 1885, his work was on the Easter edition of Harper’s Bazaar. He also did work for other magazines like Scribner's Magazine. He also illustrated a children's book in 1897, Mother Goose in Prose[1] written by L. Frank Baum.[5] By 1900, Parrish was already a member of the Society of American Artists.[7] In 1903, he traveled to Europe again to visit Italy.[3]

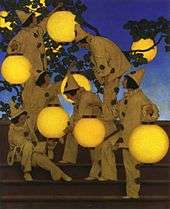

Parrish took many commissions for commercial art until the 1920s.[1] Parrish's commercial art included many prestigious projects, among which were Eugene Field's Poems of Childhood in 1904,[8] and such traditional works as Arabian Nights in 1909.[9] Books illustrated by Parrish are featured in A Wonder Book and Tanglewood Tales in 1910,[10] The Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics in 1911,[11] and The Knave of Hearts in 1925.[12]

Parrish worked with popular magazines throughout the 1910s and 1920s, including Hearst's and Life. He also worked with a number of advertising companies like Wanamaker's, Edison-Mazda Lamps, Colgate and Oneida Cutlery.[13] Parrish worked with Colliers from 1904 to 1913.[7] He received a contract to deal with exclusively for six years. He also painted advertisements for D.M. Ferry Seed Company in 1916 and 1923, which helped him gain recognition in the eye of the public.[1] His most well-known art work is Daybreak which was produced in 1923. It features female figures in a landscape scene. The painting also has undertones of Parrish blue.[5] In the 1920s, however, Parrish turned away from illustration and concentrated on painting.[14]

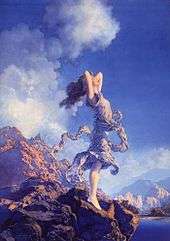

In his forties, Parrish began working on large murals instead of just focusing on children's books.[1] His works of art often featured androgynous nudes in fantastical settings. He made his living from posters and calendars featuring his works.[1] Parrish used Kitty Owen as a model in the 1920s.[14] Susan Lewin also posed for many works. She was Parrish's assistant.[15] From 1918 to 1934, Parrish worked on calendar illustrations for General Electric.[16]

In 1931, he declared to the Associated Press, "I'm done with girls on rocks", and opted instead to focus on landscapes. Though never as popular as his earlier works, he profited from them. He would often build models of the landscapes he wished to paint, using various lighting setups before deciding on a preferred view, which he would photograph as a basis for the painting (see for example, The Millpond). He lived in Plainfield, New Hampshire, near the Cornish Art Colony, and painted until he was 91 years old. He was also an avid machinist. He often referred to himself as "a mechanic who loved to paint."[17]:34 By 1935, Parrish only painted landscapes.[5] Parrish was earning over $100,000 per year by 1910, when homes were $2,000.[14] Norman Rockwell referred to Parrish as "my idol."[18]

Technique

Parrish's art is characterized by vibrant colors; the color Parrish blue was named after him. He achieved such luminous color through glazing. This process involves applying alternating bright layers of oil color separated by varnish over a base rendering.[4] Parrish usually used a blue and white monochromatic underpainting.[7]

Parrish used many other innovative techniques in his paintings. He would take pictures of models in black and white geometric prints and project the image onto his works. This technique allowed for his figures to be clothed in geometric patterns, while accurately representing distortion and draping. Parrish would also create his paintings by taking pictures, enlarging, or projecting objects. He would cut these images out and put them onto his canvas. He would later cover them with clear glaze. Parrish's technique gave his paintings a more three-dimensional feel.[19]

The outer proportions and internal divisions of Parrish's compositions were carefully calculated in accordance with geometric principles such as root rectangles and the golden ratio. In this Parrish was influenced by Jay Hambidge's theory of Dynamic Symmetry.[20]

Influence

Parrish's works continue to influence pop culture. The cover of the 1985 Bloom County cartoon collection Penguin Dreams and Stranger Things comprises elements of Daybreak, The Garden of Allah, and The Lute Players. The poster for The Princess Bride was inspired by his painting titled "Daybreak".[14] In 2001, Parrish was featured in a U.S. Post Office commemorative stamp series honoring American illustrators, including Parrish.[21]

The Elton John album Caribou has a Parrish background.[22] The Moody Blues album The Present uses a variation of the Parrish painting Daybreak for its cover. In 1984, Dali's Car, the British New Wave project of Peter Murphy and Mick Karn, used Daybreak as the cover art of their only album, The Waking Hour. The Irish musician Enya has been inspired by the works of Parrish. The cover art of her 1995 album The Memory of Trees is based on his painting The Young King of the Black Isles.[23] A number of her music videos include Parrish imagery, including "Caribbean Blue".

In the 1995 music video "You Are Not Alone", Michael Jackson and his then wife Lisa Marie Presley appear semi-nude in emulation of Daybreak.[24] The Italian singer-songwriter Angelo Branduardi's fourth album La pulce d'acqua of 1977 featured nine inlay full colour print reproduction of painter Mario Convertino's works; one of them is clearly inspired by Parrish's Stars.

Parrish's magnum opus, Daybreak, sold in 2006 for US$7.6 million.[25] The National Museum of American Illustration claims the largest body of his work in any collection, with sixty-nine works by Parrish. Some of his works are located at the Hood Museum of Art (Hanover, New Hampshire), the Cornish Colony Museum (Windsor, Vermont), and a few at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The San Diego Museum of Art toured a collection of his work in 2005.

Personal life

While studying at Drexel, Parrish met his future wife, Lydia Austen. The couple was married on June 1, 1895 and moved to Philadelphia. They would go on to have four children together.[1]

In 1898, Parrish moved to Cornish, New Hampshire with his wife and built a home that was later nicknamed "The Oaks."[2]:110 The home was surrounded by beautiful landscapes that inspired Parrish's drawings.[1]

Parrish’s youngest child, Jean, posed for Ecstasy just before leaving for Smith College. Jean was the only child to follow her parents’ profession.[27]

Parrish suffered from tuberculosis for a time in 1890.[2]:110 While sick, he discovered how to mix oils and glazes to create vibrant colors.[6] From 1900 to 1902, he painted in Saranac Lake, New York, and Hot Springs, Arizona to further recover.[3]

Parrish died on March 30, 1966 in Plainfield, New Hampshire.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Yurkoski, Natalie M. "Parrish, Maxfield". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Penn State. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Conzelman, Adrienne Ruger. After the Hunt: The Art Collection of William B. Ruger. Jan 2003: Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811700375. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Maxfield Parrish (1870-1960)". Artists & Architects. National Academy Museum. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 "The Parrish House". Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Maxfield Parrish". Collectors Weekly. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Maxfield Parrish Exhibit Currently at Chadds Ford, PA". Hagerstown, Maryland. The Morning Herald. 16 Aug 1974. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Maxfield Parrish". Illustrators. JVJ Publishing. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Field, Eugene (October 1996). Poems of Childhood. Atheneum. p. ix. ISBN 9780689807572. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Arabian Nights Book Illustrated by Maxfield Parrish Reissued". Real or Repro. Ruby Lane Inc. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "A wonder book and Tanglewood tales for boys and girls". Haiti Trust Library. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ Palgrave, Francis Turner (1911). A Golden Treasury of Song and Lyrics. Palala Press. ISBN 9781355973638. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Maxfield Parrish: The Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Murals". Tyler Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Maxfield Parrish, A Mechanic Who Painted Fantastically". New England Historical Society. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ "About Maxfield Parrish". Maxfield Parrish Art Collections. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ Jacobson, Aileen (23 Jan 2016). "The Art of Maxfield Parrish". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Cutler L.S., et al. (2007)

- ↑ McKinley, Sandra (5 Jun 2015). "Cooperstown art exhibit showcases Maxfield Parrish". The Ithaca Journal. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Maxfield Parrish". Vintage Memorabilia. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Cutler, Parrish & Cutler 1995, p. 2.

- ↑ "Interlude (The Lute Players), Maxfield Parrish". U.S. Stamp Gallery. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ "We Celebrate the 40th Anniversary of Elton's Album "Caribou"". The Official Site of Elton John. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Art Passions". Art Passions. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- ↑ "'You Are Not Alone' Video was based on Maxfield Parrish's 'Daybreak'". MJJ-777. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Quick Takes: Mel Gibson sells Maxfield Parrish's 'Daybreak' at a loss'". Los Angeles Times. 21 May 2010. Retrieved 22 Oct 2012.

- ↑ http://maxfieldparrish.info/

- ↑ http://maxfieldparrish.info/

Further reading

- Cutler, Laurence S.; Parrish, M.; & Cutler, J. G. Maxfield Parrish: A retrospective. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995. ISBN 0-87654-599-1

- Cutler, Laurence S.; Cutler, J. G.; & the National Museum of American Illustration, Maxfield Parrish and the American Imagists, Edison NJ: Chartwell Books, 2007.

- Ludwig, Coy. Maxfield Parrish. New York: Watson Guptill, 1973. ISBN 0-8230-3897-1

- Laurence S. Cutler; Judy Goffman Cutler; National Museum of American Illustration. Maxfield Parrish and the American Imagists. Edison, NJ: Wellfleet Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7858-1817-0; ISBN 978-0-7858-1817-5 (Worldcat link:

- Flacks, Erwin, Maxfield Parrish Identification and Price Guide, 4th ed. Portland, OR: Collectors Press, 2007

- Smith, Alma Gilbert, Maxfield Parrish: Master of Make-believe. London : Philip Wilson, 2005

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Maxfield Parrish |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maxfield Parrish. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Maxfield Parrish |

- Illustrators, Maxfield Parrish's glazing techniques

- The Papers of Maxfield Parrish at the Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College

- Parrish Collection at The National Museum of American Illustration

- Works by Maxfield Parrish at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Maxfield Parrish at Internet Archive

- Illustrated text of The Arabian Nights

- Maxfield Parrish Biography

- Maxfield Parrish Art Gallery

- Children's Book Illustrators Gallery – Large Archive of Maxfield Parrish's First Editions illustrations

- Maxfield Parrish artwork can be viewed at American Art Archives web site

- The Arabian Nights From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Finding aid author: Thomasina Morris (2011). "Maxfield Parrish research collection". Prepared for the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, UT. Retrieved May 29, 2016.