Man

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Masculism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Topics and issues

|

||||

|

By country

|

||||

|

Notable persons |

||||

|

Lists and categories

|

||||

|

| ||||

A man is a male human. The term man is usually reserved for an adult male, with the term boy being the usual term for a male child or adolescent. However, the term man is also sometimes used to identify a male human, regardless of age, as in phrases such as "men's basketball".

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome typically inherits an X chromosome from his mother and a Y chromosome from his father. The male fetus produces larger amounts of androgens and smaller amounts of estrogens than a female fetus. This difference in the relative amounts of these sex steroids is largely responsible for the physiological differences that distinguish men from women. During puberty, hormones which stimulate androgen production result in the development of secondary sexual characteristics, thus exhibiting greater differences between the sexes. However, there are exceptions to the above for some intersex and transgender men.

Etymology

The English term "man" is derived from a Proto-Indo-European root *man- (see Sanskrit/Avestan manu-, Slavic mǫž "man, male").[1] More directly, the word derives from Old English mann. The Old English form had a default meaning of "adult male" (which was the exclusive meaning of wer), though it could also signify a person of unspecified gender. The closely related Old English pronoun man was used just as it is in Modern German to designate "one" (e. g., in the saying man muss mit den Wölfen heulen).[2] The Old English form is derived from Proto-Germanic *mannz, "human being, person", which is also the etymon of German Mann "man, husband" and man "one" (pronoun), Old Norse maðr, and Gothic manna. According to Tacitus, the mythological progenitor of the Germanic tribes was called Mannus. *Manus in Indo-European mythology was the first man, see Mannus, Manu (Hinduism).

Age and terminology

The term manhood is used to describe the period in a human male's life after he has transitioned from boyhood, having passed through puberty, usually having attained male secondary sexual characteristics, and symbolises a male's coming of age. The word man is used to mean any adult male. In English-speaking countries, many other words can also be used to mean an adult male such as guy, dude, buddy, bloke, fellow, chap and sometimes boy or lad. The term manhood is associated with masculinity and virility, which refer to male qualities and male gender roles.

Biology and sex

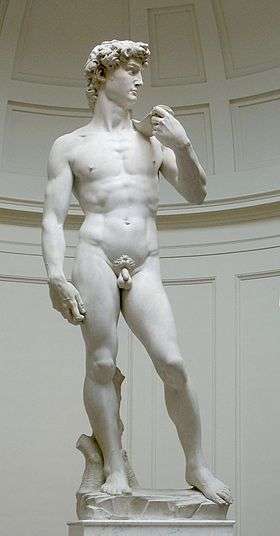

Humans exhibit sexual dimorphism in many characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability, although most of these characteristics do have a role in sexual attraction. Most expressions of sexual dimorphism in humans are found in height, weight, and body structure, though there are always examples that do not follow the overall pattern. For example, men tend to be taller than women, but there are many people of both sexes who are in the mid-height range for the species.

Some examples of male secondary sexual characteristics in humans, those acquired as boys become men or even later in life, are:

- more pubic hair

- more facial hair

- larger hands and feet

- broader shoulders and chest

- larger skull and bone structure

- larger brain mass and volume

- greater muscle mass

- a more prominent Adam's apple and deeper voice

- greater height

- a higher tibia:femur ratio (a longer shinbone in comparison to the thighbone)

Sexual characteristics

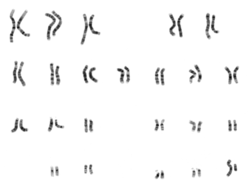

In mankind, the sex of an individual is generally determined at the time of fertilization by the genetic material carried in the sperm cell. If a sperm cell carrying an X chromosome fertilizes the egg, the offspring will typically be female (XX); if a sperm cell carrying a Y chromosome fertilizes the egg, the offspring will typically be male (XY). Persons whose anatomy or chromosomal makeup differ from this pattern are referred to as intersex.

This is referred to as the XY sex-determination system and is typical of most mammals, but quite a few other sex-determination systems exist, including some that are non-genetic.

The term primary sexual characteristics denotes the kind of gamete the gonad produces: the ovary produces egg cells in the female, and the testis produces sperm cells in the male. The term secondary sexual characteristics denotes all other sexual distinctions that play indirect roles in uniting sperm and eggs. Secondary sexual characteristics include everything from the specialized male and female features of the genital tract, to the brilliant plumage of male birds or facial hair of humans, to behavioral features such as courtship.

Gender

Biological factors are not sufficient determinants of whether a person considers themselves a man or is considered a man. Intersex individuals, who have physical and/or genetic features considered to be mixed or atypical for one sex or the other, may use other criteria in making a clear determination. There are also transgender and transsexual men, who were assigned as female at birth, but identify as men; there are varying social, legal and individual definitions with regard to these issues. (See transman.)

Reproductive system

The male sex organs are part of the reproductive system, consisting of the penis, testicles, vas deferens, and the prostate gland. The male reproductive system's function is to produce semen which carries sperm and thus genetic information that can unite with an egg within a woman. Since sperm that enters a woman's uterus and then fallopian tubes goes on to fertilize an egg which develops into a fetus or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the gestation. The concept of fatherhood and family exists in human societies. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called andrology.

Sex hormones

In mammals, the hormones that influence sexual differentiation and development are androgens (mainly testosterone), which stimulate later development of the ovary. In the sexually undifferentiated embryo, testosterone stimulates the development of the Wolffian ducts, the penis, and closure of the labioscrotal folds into the scrotum. Another significant hormone in sexual differentiation is the Anti-müllerian hormone, which inhibits development of the Müllerian ducts.

Illnesses

In general, men suffer from many of the same illnesses as women. In comparison to women, men suffer from slightly more illnesses. Male life expectancy is slightly lower than female life expectancy, although the difference has narrowed in recent years.

For males during puberty, testosterone, along with gonadotropins released by the pituitary gland, stimulates spermatogenesis, along with the full sexual distinction of a human male from a human female, while women are acted upon by estrogens and progesterones to produce their sexual distinction from the human male.

Masculinity

Masculinity has its roots in genetics (see gender).[4][5] Therefore, while masculinity looks different in different cultures, there are common aspects to its definition across cultures.[6] Sometimes gender scholars will use the phrase "hegemonic masculinity" to distinguish the most dominant form of masculinity from other variants. In the mid-twentieth century United States, for example, John Wayne might embody one form of masculinity, while Albert Einstein might be seen as masculine, but not in the same "hegemonic" fashion.

Machismo is a form of masculine culture. It includes assertiveness or standing up for one's rights, responsibility, selflessness, general code of ethics, sincerity, and respect.[7]

Anthropology has shown that masculinity itself has social status, just like wealth, race and social class. In western culture, for example, greater masculinity usually brings greater social status. Many English words such as virtue and virile (from the Indo-European root vir meaning man) reflect this.[8][9] An association with physical and/or moral strength is implied. Masculinity is associated more commonly with adult men than with boys.

A great deal is now known about the development of masculine characteristics. The process of sexual differentiation specific to the reproductive system of Homo sapiens produces a female by default. The SRY gene on the Y chromosome, however, interferes with the default process, causing a chain of events that, all things being equal, leads to testes formation, androgen production and a range of both pre-natal and post-natal hormonal effects covered by the terms masculinization or virilization. Because masculinization redirects biological processes from the default female route, it is more precisely called defeminization.

There is an extensive debate about how children develop gender identities.

In many cultures displaying characteristics not typical to one's gender may become a social problem for the individual. Among men, the exhibition of feminine behavior may be considered a sign of homosexuality, while the same is for a woman who exhibits masculine behavior. Within sociology such labeling and conditioning is known as gender assumptions and is a part of socialization to better match a culture's mores. The corresponding social condemnation of excessive masculinity may be expressed in terms such as "machismo" or "testosterone poisoning."

The relative importance of the roles of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity continues to be debated. While social conditioning obviously plays a role, it can also be observed that certain aspects of the masculine identity exist in almost all human cultures.

The historical development of gender role is addressed by such fields as behavioral genetics, evolutionary psychology, human ecology and sociobiology. All human cultures seem to encourage the development of gender roles, through literature, costume and song. Some examples of this might include the epics of Homer, the King Arthur tales in English, the normative commentaries of Confucius or biographical studies of Muhammad. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in works such as the Bhagavad Gita or bushido's Hagakure.

Culture and gender roles

_mod.jpg)

Well into prehistoric culture, men are believed to have assumed a variety of social and cultural roles which are likely similar across many groups of humans. In hunter-gatherer societies, men were often if not exclusively responsible for all large game killed, the capture and raising of most or all domesticated animals, the building of permanent shelters, the defense of villages, and other tasks where the male physique and strong spatial-cognition were most useful. Some anthropologists believe that it may have been men who led the Neolithic Revolution and became the first pre-historical ranchers, as a possible result of their intimate knowledge of animal life.

Throughout history, the roles of men have changed greatly. As societies have moved away from agriculture as a primary source of jobs, the emphasis on male physical ability has waned. Traditional gender roles for working men typically involved jobs emphasizing moderate to hard manual labor (see Blue-collar worker), often with no hope for increase in wage or position. For poorer men among the working classes, the need to support their families, especially during periods of industrial change and economic decline, forced them to stay in dangerous jobs working long arduous hours, often without retirement. Many industrialized countries have seen a shift to jobs which are less physically demanding, with a general reduction in the percentage of manual labor needed in the work force (see White-collar worker). The male goal in these circumstances is often of pursuing a quality education and securing a dependable, often office-environment, source of income.

The Men's Movement is in part a struggle for the recognition of equality of opportunity with women, and for equal rights irrespective of gender, even if special relations and conditions are willingly incurred under the form of partnership involved in marriage. The difficulties of obtaining this recognition are due to the habits and customs recent history has produced. Through a combination of economic changes and the efforts of the feminist movement in recent decades, men in some societies now compete with women for jobs that traditionally excluded women. Some larger corporations have instituted tracking systems to try to ensure that jobs are filled based on merit and not just on traditional gender selection. Assumptions and expectations based on sex roles both benefit and harm men in Western society (as they do women, but in different ways) in the workplace as well as on the topics of education, violence, health care, politics, and fatherhood - to name a few. Research has identified anti-male sexism in some areas which can result in what appear to be unfair advantages given to women.

The Parsons model was used to contrast and illustrate extreme positions on gender roles. Model A describes total separation of male and female roles, while Model B describes the complete dissolution of barriers between gender roles.[10] The examples are based on the context of the culture and infrastructure of the United States. However, these extreme positions are rarely found in reality; actual behavior of individuals is usually somewhere between these poles. The most common 'model' followed in real life in the United States and Great Britain is the 'model of double burden'.

Exclusively male roles

Some positions and titles are reserved for men only. For example, the position of Pope and Bishop in the Roman Catholic Church. Also the priesthood is exclusively male in the Catholic Church and also some other religious traditions. Men are often given priority for the position of monarch (King in the case of a man) of a country, as it usually passes to the eldest male child upon succession.

See also

Medical:

Dynamics:

Political:

References

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary, Appendix I: Indo-European Roots. man-1. Accessed 2007-07-22.

- ↑ John Richard Clark Hall: A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- ↑ The Vitruvian man

- ↑ John Money, 'The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years', Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 20 (1994): 163-77.

- ↑ Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, 'The Perception of Pain', Washington Post, 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Donald Brown, Human Universals

- ↑ Mirande, Alfredo (1997). Hombres y Machos: Masculinity and Latino Culture, p.72-74. ISBN 0-8133-3197-8.

- ↑ "Virtue (2009)". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ↑ "Virile (2009)". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ↑ Brockhaus: Enzyklopädie der Psychologie, 2001.

Further reading

- Andrew Perchuk, Simon Watney, bell hooks, The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation, MIT Press 1995

- Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination, Paperback Edition, Stanford University Press 2001

- Robert W. Connell, Masculinities, Cambridge : Polity Press, 1995

- Warren Farrell, The Myth of Male Power Berkley Trade, 1993 ISBN 0-425-18144-8

- Michael Kimmel (ed.), Robert W. Connell (ed.), Jeff Hearn (ed.), Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, Sage Publications 2004

External links

The dictionary definition of man at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of man at Wiktionary Quotations related to Man at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Man at Wikiquote Media related to Men at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Men at Wikimedia Commons