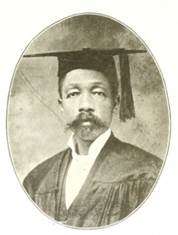

Miles Vandahurst Lynk

| Miles Vandahurst Lynk | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Miles V. Lynk published in 1919 | |

| Born |

July 3, 1871 Brownsville, TN |

| Died | December 29, 1956 |

| Education | Meharry Medical College |

| Spouse | Beebe Steven Lynk |

Early life

Dr. Miles Vandahurst Lynk was an African-American physician and author born on June 3, 1871, near Brownsville, Tennessee. He was named after two bishops, William Henry Miles and Richard H. Vandahurst, of the Christian Methodist Episcopal church in Jackson.[1] Lynk attended Meharry Medical College for two years and graduated in 1891. Later that year at the age of 19, he opened his own practice in Jackson, Tennessee, becoming the first black doctor in the town.[2]

Efforts to create opportunities for African Americans in Medicine

Lynk spent much time developing educational and professional opportunities for African American physicians. In 1890 he and his wife, Beebe Steven Lynk, established the University of West Tennessee Medical College. They took out a loan with their own home as collateral so they could purchase land for the college. He was able to provide for African Americans who could not afford to go to school and at least bring up the preparation that came in to going to medical school.[3] During the time that he was president of the medical department at the University of West Tennessee. Lynk contributed to the founding of the National Medical Association. Lynk received the Distinguished Service medal of the National Medical Association at the 57th annual convention.[4][4]

In 1892, Miles published the first national medical journal published for African American practitioners. The Medical and Surgical Observer was stamped and labeled by the Library of the Surgeon General's Office in Washington, D.C., as the "Only Negro M.J. in America." The journal connected the isolated African American medical practitioners all over the country. Although the MSO was published for only about a year, it served as a forum for black medical professionals, who were typically not welcomed in white society and medical conversations.[3] Its content informed African-American physicians of news and practical ideas throughout the world of medicine that they were not informed. Because the journal existed during a time of racial segregation, its readers found this was another way to find information in order to compete with white medical practitioners.[1][4][5]

Works

Link also published several books on African American history, including The Black Troopers; or, the Daring Heroism of the Negro Soldiers in the Spanish-American War. It discusses the lives of African American soldiers during the war. The first half the book talked strictly about the lives of black soldiers. Lynk delved into the substantial of inequality they experienced, the impact of being drafted had on the soldier’s family and the tribulations of being a soldier. The second half of the book talks about the strong soldiers who volunteered to be in the Army to serve their country regardless of the racial tension and inequality.[6] Lynk died December 29, 1956.

References

- 1 2 Savitt, Todd (1996). "A Journal of Our Own:' The Medical and Surgical Observer' at the beginnings of the Aftican American medical profession in late 19th century America.". Journal of the National Medical Association. 88 (1).

- ↑ "Miles Vanderhorst Lynk". WKNO. WKNO FM.

- 1 2 Macleish, M.Y.S. (1978). Medical education in black colleges and universities in the united states of america: an analysis of the emergence of black medical schools between 1867 and 1976. Dissertation: Harvard University.

- 1 2 3 "Miles Vandahurst Lynk". Journal of the National Medical Association. 44 (6): 475–6. 1952. PMC 2617147

. PMID 13000433.

. PMID 13000433. - ↑ Cobb, W. Montague (1981). "Recognition of The Importance of History". The Black American in Medicine. 73 (1186).

- ↑ Lynk, Miles (1889). The black troopers; or, The daring heroism of the negro soldiers in the Spanish-American war.