Tansen

| Mian Tansen (Tansen) | |

|---|---|

Mian Tansen, a depiction by Lala Deo Lal, displayed in Calcutta Gallery | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Ramtanu |

| Born |

c. 1493 Behat, Gwalior |

| Died |

1585 Agra |

| Genres | Hindustani Classical Music |

| Occupation(s) | Classical Mughal Era Vocalist |

Tansen (born 1493 or 1506 as Ramtanu – died 1586 or 1589 as Tansen) was a prominent Indian classical music composer, musician and vocalist, known for a large number of compositions, and also an instrumentalist who popularised and improved the plucked rabab (of Central Asian origin). He was among the Navaratnas (nine jewels) at the court of the Mughal Emperor Jalal ud-din Akbar. Akbar gave him the title Mian, an honorific, meaning learned man.[1]

Early life and background

Tansen as a historical personality is difficult to extract from the extensive legend that surrounds him. His father Mukund Pandey (also known as Makrand Pandey, Mukund Mishra, or Mukund Ram[2]) was a wealthy poet and accomplished musician, who for some time was a temple priest in Varanasi. Tansen's name as a child was Ramtanu.[3]

He was born at a time when a number of Persian and Central Asian motifs were fusing with Indian classical music; his influence was central to create the Hindustani classical ethos as we know today. A number of descendants and disciples have also considerably enriched the tradition. Almost all gharanas of Hindustani classical music claim some connection with the Tansen lineage. According to legend, he was noted for his imitations of animal calls and birdsong.

Career

It was only after the age of 6 that Tansen showed any musical talent. At some point, he was discipled for some time to Swami Haridas, the legendary composer from Vrindavan and part of the stellar Gwalior court of Raja Man Singh Tomar (1486–1516 AD), specialising in the Dhrupad style of singing. His talent was recognised early and it was the ruler of Gwalior who conferred upon the maestro the honorific title 'Tansen'. Haridas was considered to be a legendary teacher in that time. It is said that Tansen had no equal apart from his teacher. One legend has it that Haridas was passing through the forests when the five-year-old Ramtanu's imitation of a tiger impressed the musician saint. Another version is that his father sent him to Haridas. From Haridas, Tansen acquired not only his love for dhrupad but also his interest in compositions in the local language. This was the time when the Bhakti tradition was fomenting a shift from Sanskrit to the local idiom (Brajbhasa and Hindi), and Tansen's compositions also highlight this trend. At some point during his apprenticeship, Tansen's father died, and he returned home, where it is said he used to sing at a local Shiva temple.

In any event, Tansen went to Muhammad Ghaus who eventually became his spiritual mentor.

"However, beyond a reference of Tansen's name in a list of his disciples Mian Tansen's name is not found among the names of the Mureeds (Fans) of the Shuttari Tariqat – a Sufi spiritual lineage founded by Shaykh Muhammad Ghaus of Gwalior."[4]

The interaction with Ghaus in the Sufi tradition and the earlier training with Swami Haridas in the Bhakti tradition led to a fusion of these streams in the work of Tansen. As it is, the mystic streams of Sufism and Bhakti had considerable philosophical and stylistic overlap; Ghaus in his text Bahr-ul-Hayat (Ocean of Life) devotes several chapters to Yoga practices. In Tansen's music, we find he continues to compose in Brajbhasha invoking traditional motifs such as Krishna or Shiva.

Tansen was also influenced by other singers in the Gwalior court and also the musically proficient queen, Mriganayani (lit. doe-eyed), whose romance with the king had been forged on her singing; she remained a friend even after the death of the king. Other musicians at Gwalior may have included Baiju Bawra.

Eventually, he joined the court of King Ramachandra Baghela of Rewa, India, where he remained from 1555–1562.[5] It appears that the Mughal emperor Akbar heard of his prowess and sent his emissary Jalaluddin Qurchi to Ramachandra, who had little choice but to acquiesce, and Tansen went to Akbar's court in 1562 at the age of 57.

Tansen joined Akbar's court eventually becoming one of the treasured Navaratnas (lit. nava=nine, ratna=jewel) of his court. It was Akbar who gave him the honorific title Mian, and he is usually referred to today as Mian Tansen. Legend has it that in his first performance, he was given one hundred thousand (100,000) gold coins.

The presence of musicians like Tansen in Akbar's court has been related by historians to the theoretical position of making the empire's audible presence felt among the population, a mechanism related to Naubat or ritual performance.[6]

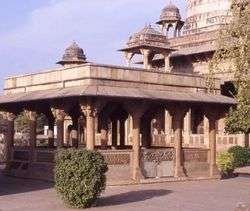

The fort at Fatehpur Sikri is strongly associated with Tansen's tenure at Akbar's court. Near the emperor's chambers, a pond was built with a small island in the middle, where musical performances were given. Today, this tank, called Anup Talao, can be seen near the public audience hall Diwan-i-Aam – a central platform reachable via four footbridges. It is said that Tansen would perform different ragas at different times of day, and the emperor and his select audience would honour him with coins. Tansen's supposed residence is also nearby.

Family

Tansen's children: Tanras Khan, Bilas Khan, Hamirsen, Suratsen and Saraswati Devi, were all musicians. She later married Naubat Khan or Ali Khan Karori( Grandson of Maharaja Samokhan Singh Rathore of Kishangarh, Samokhan Singh was a Jodhpur prince).[7] [8]

Ali Khan Karori was the finance minister(Karori) in the ministry of finance of the Mughal state at Agra. The title of Khan, Mansab, and post of Karori was given to him by Mughal Emperor Akbar. Since he was indispensable as a beenkar, he used to give Been Recitals on very special occasions to a select audience (Farmaishi). Ali Khan Karori was conferred the honorary title of Naubat khan[9] by the Mughal Emperor Jahangir.

Bilas Khan is said to have created raga Bilaskhani Todi after Tansen's death; an interesting legend of this improvisation (it differs only in detail from Tansen's Todi), has it that Bilas composed it while grief-stricken at the wake itself, and that Tansen's corpse moved one hand in approval of the new melody. It has been heard that Tansen had the power to light up fire with his song called Raag Deepak and he had taught his Daughter to bring rain by singing the Megh Malhar.

Tansen's blood descendants (the "Senia Gharana") held considerable prestige in musical circles for several centuries. The royal courts of Rewa, Mughal Empire, Rampur, Awadh, Banaras, Banda, Jhansi and Jaipur among others, retained many noted members of Tansen lineage.The noted members of the family of Misri Singh and Tansen are as follows,

Bilas Khan's son in law, Lal Khan Gunsmundra (Son of Naubaat Khan, chief musician of Shahjahan, Grandfather of Niyamat Khan Sadarang, Title of Gunsamundra conferred by Shahjahan on 19 November 1637[10]).[11] Shahjahan gave an elephant to Lal Khan on 18 October 1642,[10] Honored Lal Khan with Awards on Nauroz Shamsi, 1645.[10] Gave Cash Award of 4000 in 1645 and 6 months later gave 1000 cash Award.[10]

Lal Khan 'Gunsamundra' (Son of Naubaat Khan) had 4 prolific sons Khush hal Khan GunSamundra, Bisram Khan, Miyan Manrang or Maharang, and Bhupat Khan.[8] The Life and work of Wazir Khan of Rampur, and the prominent disciples of Wazir Khan,Research by Rati Rastogi, RohilKhand University, Barailley.[7][12]

Shahjahan conferred on Khushal Khan the title of GunSamundra in 1655.,[13] after the death of Lal Khan GunSamundra

Bhupat Khan had son by the name of Sidhar Khan 'Dadhi'.[12] When we add Dadhi to a person's name it means that the said person is a musician.[14] Sidhar Khan was the contemporary of Niyamat Khan Sadarang and first cousin of Sadarang and nephew(Bhateeje) of Nirmol Shah.Nirmol Shah had two sons Niyamat Khan Sadarang and Naubaat Khan Sani(Naubaat Khan II, Chote Shah sahab).[7][12] Sidhar Khan invented Tabla,[8] and was the Founder of the Delhi tabla gharānā, during Muhammad Shah reign.[15]

Niyamat Khan Sadarang, who was one of the most influential musicians of the 18th century, had a brilliant career as singer-composer and binkar under the aegis of the Emperor Muhammad Shah (reign: 1719–1748). He wrote myriad compositions under the pen name of Sadarang.

Dargah Quli Khan, a young noble deccani who lived in Delhi between 1737 and 1741, had the opportunity to hear Na’mat Khan play the bin. He wrote:... "When he begins to play the bin, when the notes of the bin throw a spell on the world, the party enters a strange state: people begin to flutter like fish out of water (...). Na’mat Khan is acquainted with all aspects of music. Na’mat Khan is considered unequalled and is the pride of the people of Delhi." (Khan 1933: 66–67; Miner 1993: 85).

Feroz Khan Adarang (created Ferozkhanitodi,invented Sitar,[8] nephew of Sadarang, great grandfather of Nayak Wazir Khan).[16][17] When Nader Shah sacked Delhi, Tansen's and Naubaat Khan's descendants, went outside Delhi for patronage and Feroz Khan Adarang, Karim Sen and Mehndi Sen(ancestors of Bahadur Hussain Khan), Gulab Khan and Turab Khan were guest artists at the court of Nawab of Rampur Ali Mohammad Khan and his son Nawab Sadullah Khan at Atarchen'di Aonla, Uttar Pradesh.[7]

Nayak of Kalb Ali Khan court Bahadur Hussain Khan (Zia-ud-Daula, title conferred by Wajid Ali Shah, son of Jeevan Shah of Jhansi, grandson of Miyan Manrang, nephew(Bhaanje) of Pyar Khan of Awadh, maternal Grandson of Sadarang),[18][19] Jeevan Shah was the famous Sufi saint of Jhansi Bundelkhand.[20] His complex in Jhansi is a major tourist attraction. Jeevan Shah was the son-in-law of Chajju Khan.[8]

Ameer Khan Beenkar (Dhrupatiye beenkar, Nephew of Adarang, Son of Omrao Khan beenkar, father of Nayak Wazir Khan,son in law of Kazim Ali Khan, Rahat-ud-Daulah a.k.a Badku miyan. Badku miyan was the son of Jafar khan of Awadh and Banaras court),.[21][22][23] Performed Haj with Nawab Kalb Ali Khan in the year 1872.[24] Ameer Khan spent his childhood days with his childhood friend Daagh and Mughal Princes at the Delhi Red Fort. Ameer Khan Beenkar's portrait published in Musaddas Benazeer, depicts him wearing a shawl and a Dastar( honorary head gear). The shawl and the dastar were given by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah.[8]

Roshan Khan Dagar (the last master of Dagar bani, buried at his personal space Roshan Bagh near western wall of Raza Sugar mill).[7]

Jafar Khan (Son of Famous Tanseni Chajju Khan and brother of Pyar Khan and Basit Khan of Awadh and Banaras,Chief musician at Awadh and Banaras court,created Raag tilak kamod,invented Sursingar,[7][25] buried at his personal space of Dongar Bagh, near police line Rampur).[26][27]

Nayak Wazir Khan (Rampur) (master of Hamid Ali Khan of Rampur,[28]Allauddin Khan, Hafiz Ali Khan, Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande). Wazir Khan, who is of Saraswati Devi lineage, was also a musicologist who wrote the Risala Mousibi.Wazir Khan was the student of Daagh in Poetry.[7] Mohammed Ali Khan (son of Basit Khan, Maternal grandson of Sadarang).[29]

One of the last of the line, Dr Dabir Khan( 1905–1972, Saraswati Devi lineage, grandson of Nayak Wazir Khan) was a dhrupadiya and a beenkar, at Radio Calcutta.

The last living descendants are Imtiaz Ali khan Khandara[30] and greatnephew Shabbir Khan Khandara.

Musical legacy

The legendary musical prowess of Tansen surpasses all other legends in Indian music. In terms of influence, he can be compared to the prolific Sufi composer Amir Khusro (1253–1325), or to Bhakti tradition composers such as Swami Haridas.

Even today, no one has reach near to his compositions.

Several of his raga compositions have become mainstays of the Hindustani tradition, and these are often prefaced with Mian ki ("of the Mian"), e.g. Mian ki Todi, Mian ki Malhar, Mian ki Mand, Mian ka Sarang; in addition he is the composer of major ragas like Darbari Kanada, Darbari Todi, and Rageshwari.

Tansen also authored Sangeeta Sara and Rajmala which constitute important documents on music.

Almost every gharana (school) tries to trace its origin to him. Though the Dagar family of dhrupad singers believe themselves to be the direct descendants of not Tansen but his guru, Haridas Swami. As for the Dhrupad style of singing, this was formalised essentially through the practice by composers like Tansen and Haridas, as well as others like Baiju Bawra who may have been a contemporary.

After Tansen, some of the ideas from the rabab were fused with the traditional Indian stringed instrument, veena; one of the results of this fusion is the instrument sarod, which does not have frets and is popular today because of its perceived closeness to the vocal style.

The famous qawwals, the Sabri Brothers claim lineage from Mian Tansen This information of Sabri brothers being the descendant of Mian Tansen is completely wrong. This has been confirmed by Imtiaz Ali Khan,the last descendant of Mian Tansen.[31]

Tansen award

A national music festival known as 'Tansen Samaroh' is held every year in December, near the tomb of Tansen at Behat as a mark of respect to his memory. The Tansen Samman or Tansen award is given away to exponents in Hindustani Classical music.

Legends

The bulk of Tansen's biography as it is handed down in the musical literature consists of legends.[1] Among the legends about Tansen are stories of his bringing down the rains with Raga Megh Malhar and lighting lamps with the legendary raga Deepak.[32][33] Raga Megh Malhar is still in the mainstream repertoire, but raga Deepak is no longer known; three different variants exist in the Bilawal, Poorvi and Khamaj thaats. It is not clear which, if any, corresponds to the Deepak of Tansen's time. There is a popular myth that it disappeared because it could indeed bring fire, and so was simply too dangerous to sing. Other legends tell of his ability to bring wild animals to listen with attention (or to talk their language). Once, a wild white elephant was captured, but it was fierce and could not be tamed. Finally, Tansen sang to the elephant who calmed down and the emperor was able to ride him. Such was the power of his music that when he used to sing in the court of Akbar, it is said that candles used to light up automatically.

Many admirers are convinced that his death was caused by a fire while he was singing the raga Deepaka.

Wazir Khan who is of Saraswati Devi Lineage, attended a conference on music in Kolkata where number of Rajas and Nawabs were present, including Raja of Gauripur. Wazir Khan along with other musicians performed there. Before the performance he asked the attendant at the conference hall to put off the candles in one of the Chandelier's of the conference hall. He started playing the Rudra Veena and it happened for a moment that the Chandelier lit up in the glow of candles and the very next moment it came crashing down to the ground.[34]

Death

According to one version of the story, Tansen died on 26 April 1586 in Delhi c-8246 c, and that Akbar and much of his court attended the funeral procession.[35] Other versions give 6 May 1589 as the date of his death. Tansen was buried in the mausoleum complex of his Sufi master Shaikh Muhammad Ghaus in Gwalior. According to legend, Tansen's son Bilas Khan, in his grief, composed Bilaskhani Todi.

Every year in December, an annual festival, the Tansen Samaroh, is held in Gwalior to celebrate Tansen.[36]

Popular culture

Several Hindi films have been made on Tansen's life, with mostly anecdotal storylines. Some of them are Tansen (1943), a musical hit produced by Ranjit Movietone, starring K. L. Saigal and Khursheed Bano.[37] Tansen (1958) and Sangeet Samrat Tansen (1962). Tansen is also a central character, though remaining mostly in the backdrop, in the historical musical Baiju Bawra (1952), based on the life of his eponymous contemporary.

Tansen's story was extensively researched and showcased in a Pakistan Television's series in the late 1980s where the classical singer's entire life was explored. The series was written by Haseena Moin.

An advertisement of GE shows a musician singing in a royal hall and his ability to light the lamps with his voice, resembling the legend of raag deepak which Tansen was famous for.

References

- 1 2 Davar, Ashok (1987). Tansen – The Magical Musician. India: National book trust.

- ↑ Sunita Dhar (1989). Senia gharana, its contribution to Indian classical music. Reliance. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-85047-49-2.

- ↑ "PROFILE: TANSEN — the mesmerizing maestro".

- ↑ "Dargah Hazrat Ghouse – Gwalior". Shuttari al Hashmi – Blog. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ S K Banerjee (2003). "The classical music tradition of Rewa (M.P.) in the 19th and 20th century A.D". Journal of the ITC-SRA. 17.

- ↑ Wade, Bonnie C. (1998). Imaging Sound : An Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art, and Culture in Mughal India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-86840-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tareekh-e-Rohela by W.H. Siddiqui

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Life and work of Wazir Khan of Rampur, and the prominent disciples of Wazir Khan,Research by Rati Rastogi, RohilKhand University, Barailey

- ↑ Memoirs of Jahangir, Royal Asiatic Society London

- 1 2 3 4 Islamic Culture Journal,by Prof. Abdul Haleem, October 1945,P.P 357-386

- ↑ Romance of the Raga,By Vijaya Moorthy

- 1 2 3 Shajra-e-Nasab Janab Miyan Tansen and Naubaat Khan

- ↑ Islamic Culture Journal by Prof. Abdul Haleem,October 1945, P.P 357-386

- ↑ Shabdavali,Musaddas Tahniyat-e-Jashn-e- Benazeer, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Music of India, Saṅgīt Mahābhāratī

- ↑ Shajra-e-nasab Janab Miyan Tansen and Maharaja Samokhan Singh Rathore of Kishangarh

- ↑ Akhbarul Sanadeed by Maulvi Najmul Ghani,Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Akhbarul Sanadeed by Maulvi Najmul Ghani 1878, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Musaddas Benazir, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Musaddas Benazeer, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Akhbarul sanadeed by Maulvi Najmul Ghani,Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Musaddas Tahniyat-e- jashn-e Benazeer by Meer Yaar Ali Jaan Saheb, Ranpur Raza Library

- ↑ Rampur ki Sadarang parampara by Saryu Kalekar, New Delhi Publications

- ↑ Musaddas Benazeer, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Musaddas Benazeer

- ↑ Madan ul mausiqui, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Rampur ki Sadarang Parampara by Saryu Kalekar,New Delhi Publication

- ↑ Rampur ki Sadarang Parampara by Saryu Kalekar,1984 New Delhi Publications

- ↑ Akhbarul Sanadeed,Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Musaddas Tahniyat-e- Jashn-e- Benazir by Meer Yaar Ali Jaan Sahab, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ Musaddas-Tahniyat-e- Jashn-e- Benazir by Meer Yaar Ali Jaan Saheb, Rampur Raza Library

- ↑ "Indian Classical Music – The Science and Significance".

- ↑ Deva, Bigamudre (1995). Indian Music. India: Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Roznamcha (Daily Notes), Raja of Gauripur, Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad

- ↑ Maryam Juzer Kherulla (12 October 2002). "Profile: Tansen — the mesmerizing maestro". Dawn. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ↑ "Strains of a raga ... in Gwalior". The Hindu. 11 January 2004. report on the annual Tansen Samaroh in Gwalior. Also has picture of his mausoleum

- ↑ Nettl, Bruno; Arnold, Alison (2000). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. Taylor & Francis. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tansen. |