Monochromator

A monochromator is an optical device that transmits a mechanically selectable narrow band of wavelengths of light or other radiation chosen from a wider range of wavelengths available at the input. The name is from the Greek roots mono-, "single", and chroma, "colour", and the Latin suffix -ator, denoting an agent.

Uses

A device that can produce monochromatic light has many uses in science and in optics because many optical characteristics of a material are dependent on wavelength. Although there are a number of useful ways to select a narrow band of wavelengths (which, in the visible range, is perceived as a pure color), there are not as many other ways to easily select any wavelength band from a wide range. See below for a discussion of some of the uses of monochromators.

In hard X-ray and neutron optics, crystal monochromators are used to define wave conditions on the instruments.

Techniques

A monochromator can use either the phenomenon of optical dispersion in a prism, or that of diffraction using a diffraction grating, to spatially separate the colors of light. It usually has a mechanism for directing the selected color to an exit slit. Usually the grating or the prism is used in a reflective mode. A reflective prism is made by making a right triangle prism (typically, half of an equilateral prism) with one side mirrored. The light enters through the hypotenuse face and is reflected back through it, being refracted twice at the same surface. The total refraction, and the total dispersion, is the same as would occur if an equilateral prism were used in transmission mode.

Collimation

The dispersion or diffraction is only controllable if the light is collimated, that is if all the rays of light are parallel, or practically so. A source, like the sun, which is very far away, provides collimated light. Newton used sunlight in his famous experiments. In a practical monochromator, however, the light source is close by, and an optical system in the monochromator converts the diverging light of the source to collimated light. Although some monochromator designs do use focusing gratings that do not need separate collimators, most use collimating mirrors. Reflective optics are preferred because they do not introduce dispersive effects of their own.

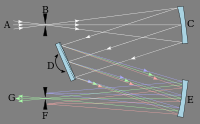

Czerny–Turner monochromator

In the common Czerny–Turner design,[1] the broad-band illumination source (A) is aimed at an entrance slit (B). The amount of light energy available for use depends on the intensity of the source in the space defined by the slit (width × height) and the acceptance angle of the optical system. The slit is placed at the effective focus of a curved mirror (the collimator, C) so that the light from the slit reflected from the mirror is collimated (focused at infinity). The collimated light is diffracted from the grating (D) and then is collected by another mirror (E), which refocuses the light, now dispersed, on the exit slit (F). In a prism monochromator, a reflective prism takes the place of the diffraction grating, in which case the light is refracted by the prism.

At the exit slit, the colors of the light are spread out (in the visible this shows the colors of the rainbow). Because each color arrives at a separate point in the exit-slit plane, there are a series of images of the entrance slit focused on the plane. Because the entrance slit is finite in width, parts of nearby images overlap. The light leaving the exit slit (G) contains the entire image of the entrance slit of the selected color plus parts of the entrance slit images of nearby colors. A rotation of the dispersing element causes the band of colors to move relative to the exit slit, so that the desired entrance slit image is centered on the exit slit. The range of colors leaving the exit slit is a function of the width of the slits. The entrance and exit slit widths are adjusted together.

Stray light

The ideal transfer function of such a monochromator is a triangular shape. The peak of the triangle is at the nominal wavelength selected. The intensity of the nearby colors then decreases linearly on either side of this peak until some cutoff value is reached, where the intensity stops decreasing. This is called the stray light level. The cutoff level is typically about one thousandth of the peak value, or 0.1%.

Spectral bandwidth

Spectral bandwidth is defined as the width of the triangle at the points where the light has reached half the maximum value (full width at half maximum, abbreviated as FWHM). A typical spectral bandwidth might be one nanometer; however, different values can be chosen to meet the need of analysis. A narrower bandwidth does improve the resolution, but it also decreases the signal-to-noise ratio.[2]

Dispersion

The dispersion of a monochromator is characterized as the width of the band of colors per unit of slit width, 1 nm of spectrum per mm of slit width for instance. This factor is constant for a grating, but varies with wavelength for a prism. If a scanning prism monochromator is used in a constant bandwidth mode, the slit width must change as the wavelength changes. Dispersion depends on the focal length, the grating order and grating resolving power.

Wavelength range

A monochromator's adjustment range might cover the visible spectrum and some part of both or either of the nearby ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) spectra, although monochromators are built for a great variety of optical ranges, and to a great many designs.

Double monochromators

It is common for two monochromators to be connected in series, with their mechanical systems operating in tandem so that they both select the same color. This arrangement is not intended to improve the narrowness of the spectrum, but rather to lower the cutoff level. A double monochromator may have a cutoff about one millionth of the peak value, the product of the two cutoffs of the individual sections. The intensity of the light of other colors in the exit beam is referred to as the stray light level and is the most critical specification of a monochromator for many uses. Achieving low stray light is a large part of the art of making a practical monochromator.

Diffraction gratings and blazed gratings

Grating monochromators disperse ultraviolet, visible, and infrared radiation typically using replica gratings, which are manufactured from a master grating. A master grating consists of a hard, optically flat, surface that has a large number of parallel and closely spaced grooves. The construction of a master grating is a long, expensive process because the grooves must be of identical size, exactly parallel, and equally spaced over the length of the grating (3–10 cm). A grating for the ultraviolet and visible region typically has 300–2000 grooves/mm, however 1200–1400 grooves/mm is most common. For the infrared region, gratings usually have 10–200 grooves/mm.[3] When a diffraction grating is used, care must be taken in the design of broadband monochromators because the diffraction pattern has overlapping orders. Sometimes broadband preselector filters are inserted in the optical path to limit the width of the diffraction orders so they do not overlap. Sometimes this is done by using a prism as one of the monochromators of a dual monochromator design.

The original high-resolution diffraction gratings were ruled. The construction of high-quality ruling engines was a large undertaking (as well as exceedingly difficult, in past decades), and good gratings were very expensive. The slope of the triangular groove in a ruled grating is typically adjusted to enhance the brightness of a particular diffraction order. This is called blazing a grating. Ruled gratings have imperfections that produce faint "ghost" diffraction orders that may raise the stray light level of a monochromator. A later photolithographic technique allows gratings to be created from a holographic interference pattern. Holographic gratings have sinusoidal grooves and so are not as bright, but have lower scattered light levels than blazed gratings. Almost all the gratings actually used in monochromators are carefully made replicas of ruled or holographic master gratings.

Prisms

Prisms have higher dispersion in the UV region. Prism monochromators are favored in some instruments that are principally designed to work in the far UV region. Most monochromators use gratings, however. Some monochromators have several gratings that can be selected for use in different spectral regions. A double monochromator made by placing a prism and a grating monochromator in series typically does not need additional bandpass filters to isolate a single grating order.

Focal length

The narrowness of the band of colors that a monochromator can generate is related to the focal length of the monochromator collimators. Using a longer focal length optical system also unfortunately decreases the amount of light that can be accepted from the source. Very high resolution monochromators might have a focal length of 2 meters. Building such monochromators requires exceptional attention to mechanical and thermal stability. For many applications a monochromator of about 0.4 meter focal length is considered to have excellent resolution. Many monochromators have a focal length less than 0.1 meter.

Slit height

The most common optical system uses spherical collimators and thus contains optical aberrations that curve the field where the slit images come to focus, so that slits are sometimes curved instead of simply straight, to approximate the curvature of the image. This allows taller slits to be used, gathering more light, while still achieving high spectral resolution. Some designs take another approach and use toroidal collimating mirrors to correct the curvature instead, allowing higher straight slits without sacrificing resolution.

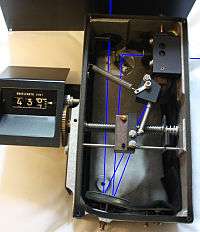

Wavelength vs energy

Monochromators are often calibrated in units of wavelength. Uniform rotation of a grating produces a sinusoidal change in wavelength, which is approximately linear for small grating angles, so such an instrument is easy to build. Many of the underlying physical phenomena being studied are linear in energy though, and since wavelength and energy have a reciprocal relationship, spectral patterns that are simple and predictable when plotted as a function of energy are distorted when plotted as a function of wavelength. Some monochromators are calibrated in units of reciprocal centimeters or some other energy units, but the scale may not be linear.

Dynamic range

A spectrophotometer built with a high quality double monochromator can produce light of sufficient purity and intensity that the instrument can measure a narrow band of optical attenuation of about one million fold (6 AU, Absorbance Units).

Applications

Monochromators are used in many optical measuring instruments and in other applications where tunable monochromatic light is wanted. Sometimes the monochromatic light is directed at a sample and the reflected or transmitted light is measured. Sometimes white light is directed at a sample and the monochromator is used to analyze the reflected or transmitted light. Two monochromators are used in many fluorometers; one monochromator is used to select the excitation wavelength and a second monochromator is used to analyze the emitted light.

An automatic scanning spectrometer includes a mechanism to change the wavelength selected by the monochromator and to record the resulting changes in the measured quantity as a function of the wavelength.

If an imaging device replaces the exit slit, the result is the basic configuration of a spectrograph. This configuration allows the simultaneous analysis of the intensities of a wide band of colors. Photographic film or an array of photodetectors can be used, for instance to collect the light. Such an instrument can record a spectral function without mechanical scanning, although there may be tradeoffs in terms of resolution or sensitivity for instance.

An absorption spectrophotometer measures the absorption of light by a sample as a function of wavelength. Sometimes the result is expressed as percent transmission and sometimes it is expressed as the inverse logarithm of the transmission. The Beer–Lambert law relates the absorption of light to the concentration of the light-absorbing material, the optical path length, and an intrinsic property of the material called molar absorptivity. According to this relation the decrease in intensity is exponential in concentration and path length. The decrease is linear in these quantities when the inverse logarithm of transmission is used. The old nomenclature for this value was optical density (OD), current nomenclature is absorbance units (AU). One AU is a tenfold reduction in light intensity. Six AU is a millionfold reduction.

Absorption spectrophotometers often contain a monochromator to supply light to the sample. Some absorption spectrophotometers have automatic spectral analysis capabilities.

Absorption spectrophotometers have many everyday uses in chemistry, biochemistry, and biology. For example, they are used to measure the concentration or change in concentration of many substances that absorb light. Critical characteristics of many biological materials, many enzymes for instance, are measured by starting a chemical reaction that produces a color change that depends on the presence or activity of the material being studied.[4] Optical thermometers have been created by calibrating the change in absorbance of a material against temperature. There are many other examples.

Spectrophotometers are used to measure the specular reflectance of mirrors and the diffuse reflectance of colored objects. They are used to characterize the performance of sunglasses, laser protective glasses, and other optical filters. There are many other examples.

In the UV, visible and near IR, absorbance and reflectance spectrophotometers usually illuminate the sample with monochromatic light. In the corresponding IR instruments, the monochromator is usually used to analyze the light coming from the sample.

Monochromators are also used in optical instruments that measure other phenomena besides simple absorption or reflection, wherever the color of the light is a significant variable. Circular dichroism spectrometers contain a monochromator, for example.

Lasers produce light which is much more monochromatic than the optical monochromators discussed here, but only some lasers are easily tunable, and these lasers are not as simple to use.

Monochromatic light allows for the measurement of the quantum efficiency (QE) of an imaging device (e.g. CCD or CMOS imager). Light from the exit slit is passed either through diffusers or an integrating sphere on to the imaging device while a calibrated detector simultaneously measures the light. Coordination of the imager, calibrated detector, and monochromator allows one to calculate the carriers (electrons or holes) generated for a photon of a given wavelength, QE.

See also

- Atomic absorption spectrometers use light from hollow cathode lamps that emit light generated by atoms of a specific element, for instance iron or lead or calcium. The available colors are fixed, but are very monochromatic and are excellent for measuring the concentration of specific elements in a sample. These instruments behave as if they contained a very high quality monochromator, but their use is limited to analyzing the elements they are equipped for.

- A major IR measurement technique, Fourier transform IR, or FTIR, does not use a monochromator. Instead, the measurement is performed in the time domain, using the field autocorrelation technique.

- Polychromator

- Ultrafast monochromator – a monochromator that compensates for path length delays that would stretch ultrashort pulses

- Wien filter – a technique for producing "monochromatic" electron beams, where all the electrons have nearly the same energy

References

- ↑ Czerny, M.; Turner, A. F. (1930). "Über den astigmatismus bei spiegelspektrometern.". Zeitschrift für Physik. 61 (11–12): 792–797. Bibcode:1930ZPhy...61..792C. doi:10.1007/BF01340206.

- ↑ Keppy, N. K. and Allen M., Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA, 2008

- ↑ Skoog, Douglas (2007). Principles of Instrumental Analysis. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-0-495-01201-6.

- ↑ Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, et al. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th edition. New York: W. H. Freeman; 2000. Section 3.5, Purifying, Detecting, and Characterizing Proteins. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21589/

External links

- Discusses monochromator design in great detail

- Palmer, Christopher (2005). Diffraction Grating Handbook (6th ed.). Newport Corporation.

- "Optical systems using plane gratings". Richardson Gratings. Archived from the original on 2008-09-15.

- "Optical systems using concave gratings". Richardson Gratings. Archived from the original on 2008-09-15.

- Double folded-z-configuration monochromator. U.S. Patent RE26,053E - contains an extended discussion of the design rationale of this UV-VIS-NIR monochromator