Morin khuur

|

Sambuugiin Pürevjav of Altai Khairkhan performing in Paris in 2005. | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Matouqin, Шоор (Shoor), Икил (Ikil) |

| Classification | Bowed string instrument |

| Related instruments | |

| Byzaanchy, Igil, Gusle, Kobyz | |

| More articles | |

| Music of Mongolia | |

The morin khuur (Mongolian: морин хуур), also known as the horsehead fiddle, is a traditional Mongolian bowed stringed instrument. It is one of the most important musical instruments of the Mongol people, and is considered a symbol of the Mongolian nation. The morin khuur is one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity identified by UNESCO.

Name

The full Classical Mongolian name for the morin khuur is morin toloγai tai quγur, ᠮᠣᠷᠢᠨ

ᠲᠣᠯᠣᠭᠠᠢ ᠲᠠᠢ

ᠬᠣᠭᠣᠷ, (which in modern Khalkh cyrillic is Морин толгойтой хуур) meaning fiddle with a horse's head. Usually it is abbreviated as "Морин хуур", "ᠮᠣᠷᠢᠨ

ᠬᠣᠭᠣᠷ", Latin transcription "Morin huur". In western Mongolia it is known as ikil (Mongolian: икил—not to be confused with the similar Tuvan igil)—while in eastern Mongolia it is known as shoor (Mongolian: Шоор).[1]

Construction

The instrument consists of a trapezoid wooden-framed sound box to which two strings are attached. It is held nearly upright with the sound box in the musician's lap or between the musician's legs. The strings are made from hairs from nylon or horses' tails,[2] strung parallel, and run over a wooden bridge on the body up a long neck, past a second smaller bridge, to the two tuning pegs in the scroll, which is usually carved into the form of a horse's head.

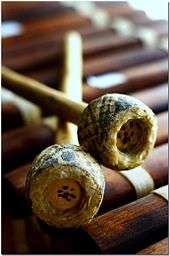

The bow is loosely strung with horse hair coated with larch or cedar wood resin, and is held from underneath with the right hand. The underhand grip enables the hand to tighten the loose hair of the bow, allowing very fine control of the instrument's timbre.

The larger of the two strings (the "male" string) has 130 hairs from a stallion's tail, while the "female" string has 105 hairs from a mare's tail. Nowadays the strings are made of nylon. Traditionally, the strings were tuned a fifth apart, though in modern music they are more often tuned a fourth apart, usually to B-flat and F. The strings are stopped either by pinching them in the joints of the index and middle fingers, or by pinching them between the nail of the little finger and the pad of the ring finger.

Traditionally, the frame is covered with camel, goat, or sheep skin, in which case a small opening would be left in back. But since the 1970s, new all-wood sound box instruments have appeared, with carved f-holes similar to European stringed instruments.[3]

Nowadays the standard size in total is 1,15 m, the distance between the upper bridge and the lower bridge is about 60 cm, but especially the upper bridge can be adapted to match smaller player's fingers. The sound box has usually a depth of 8–9 cm, the dimension of the soundbox is about 20 cm at the top and 25 cm at the bottom. Good quality instruments can achieve a strength of 85 dBA, which allows to play it (if desired) even in mezzoforte or crescendo. When horsehair is used, the luthiers prefer to use the hair of white stallions. In general the quality of a horse hair string depends on its preparation, the climate conditions and the nutrition of the animals. That gives a wide area of quality differences.

Quality nylon strings (Khalkh Mongolian "сатуркан халгас") last for up to 2 years, but only if prepared and placed properly on the instrument. Most beginners don't comb the strings, then the sound quality worsens quickly. Good strings nearly sound like steel strings, and in spectrograms they show about 7-8 harmonics.

Morin khuur vary in form depending on region. Instruments from central Mongolia tend to have larger bodies and thus possess more volume than the smaller-bodied instruments of Inner Mongolia. Also the Inner Mongolian instruments have mostly mechanics for tightening the strings, where Mongolian luthiers mostly use wooden pegs in a slightly conic shape. In Tuva, the morin khuur is sometimes used in place of the igil.

Origin

|

"Buyant Altai Khairkhan" (Altai Khairkhan, 2000)

The sound of a morin khuur |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Around 2000 years ago throughout Asia various musical instruments spread through various local design modifications, although some different Asian countries tend to belong Morin Khuur as theirs, in Mongolia current design version was evolved and adopted locally. From ancient times Mongols are horse riding nomadic civilization hence they developed their prime livelhood related musical instrument design for themselves.

One legend about the origin of the morin khuur is that a shepherd named Namjil the Cuckoo received the gift of a flying horse; he would mount it at night and fly to meet his beloved. A jealous woman had the horse’s wings cut off, so that the horse fell from the air and died. The grieving shepherd made a horsehead fiddle from the now-wingless horse's skin and tail hair, and used it to play poignant songs about his horse.

Another legend credits the invention of the morin khuur to a boy named Sükhe (or Suho). After a wicked lord slew the boy's prized white horse, the horse's spirit came to Sükhe in a dream and instructed him to make an instrument from the horse's body, so the two could still be together and neither would be lonely. So the first morin khuur was assembled, with horse bones as its neck, horsehair strings, horse skin covering its wooden soundbox, and its scroll carved into the shape of a horse head.

Chinese history credits the evolution of the matouqin from the xiqin, a family of instruments found around the Shar Mören River valley (not to be confused with the Yellow River) in what is now Inner Mongolia. It was originally associated with the Xi people. In 1105 (during the Northern Song Dynasty), it was described as a foreign, two-stringed lute in an encyclopedic work on music called Yue Shu by Chen Yang. In Inner Mongolia, the matouqin is classified in the huqin family, which also includes the erhu.

The fact that most of the eastern Turkic neighbors of the Mongols possess similar horse hair instruments (such as the Tuvan igil, the Kazakh kobyz, or the Kyrgyz Kyl kyyak), though not western Turkic, may point to a possible origin amongst peoples that once inhabited the Mongolian Steppe, and migrated to what is now Tuva, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

It is to be noted that the gusle from Southeastern Europe (Serbia, Croatia & Albania) is a very similar instrument, and may indicate this is an extremely ancient instrument perhaps even dating back to the outward migration of people out of the Middle East and Central Asia some 40,000 years ago. Often these instruments are depicted with a goat head instead of a horse in Europe.

Playing technique

The modern style Morin Khuur is played with nearly natural finger positions. That means, the distance between two fingers usually make the distance of a half tone on the lower section of the instrument. On the tune F / B♭ the index finger hits on the low (F) string the G, the middle finger hits the G♯, the ring finger hits the A, the little finger the B flat. Identical positions are on the high strings - C, C♯, D, D♯. The little finger tips the B strings under the F string, while all other fingers touch the strings from the top.

Melodies are usually played from F to F' on the F string, then the player switches to the B♭ string and continues with G, A, B♭. There are 3 hand positions on the F string, and 2 positions on the B♭ strings a musician must memorize. The idea is that without moving the string hand too much the sound quality improves. The 2nd hand position on the B string is used to play C, D, E♭, then moves a little bit for hitting the F' with the little finger, then without moving the G position can be reached with the 1st finger.

It is also possible to touch the B♭ string with the thumb to get a C, and use the ring finger under the F string to achieve the D♯.

On the F strings only the first harmonic is used, so the scale ranges from F to F'. On the B♭ strings several harmonics are available: B♭', F", B", also often players accompanying the F' on the F string with an F" overtone at the F' position on the B♭ string.

Some parts of the bowing technique is unique - the little and the ring finger of the right hand usually touch the bow hair, which is used for setting accents. The other two fingers maintain a slight pressure on the strings. A common technique with other string instruments is the "Kist". When the bow direction changes, the right hand moves a little bit in advance to the opposite direction to avoid scratchy sounds and for achieving a better voice. When pushing the bow the hand closes a little bit in direction of a fist, when pulling it the hand opens - nearly to a right angle between the arm and the fingers.

The instrument can be used for playing western style classical music, or Mongolian style pieces. The primary education is to learn the scales, to train the ear for achieving the "muscle memory", the ability to automatically adapt the finger position when a note wasn't hit properly. The main goal is to achieve a "clear" sound, that means no change in volume or frequency is desired. That depends on three main facts:

- finger force used for touching the strings - pressure of the bow - constant sound after bow direction changes

As variation are usually used the "accent" and the "vibrato". Other techniques like the "Col legno", the "Pizzicato" or the "Martellato" are generally not used on the Morin Huur.

Because of its standard tune to Bb and F mostly western music is transposed for being played in one of the four most common scales: F major, F minor, B♭ Major, E♭ major. When used as a solo instrument the Morin Huur is often tuned a half tone higher or lower.

Nearly all of the Mongolian style pieces are in F minor, and often the instrument is tuned 1-2 notes lower for coming closer to the tunes used in the deep past. The instruments in the pre-socialist era of Mongolia were usually covered with skin, which mostly doesn't allow the Bb and F tune - usually tuned 2-4 notes deeper.

On the contemporary Morin Khuur the deep string is placed at the right side and the high string is placed at the left side, seen from the front of the instrument. The Igil has the opposite placement of strings, so a player has to adapt in order to play pieces made for the other one. For contemporary teaching the modern style is in use.

Education

In Mongolia the morin khuur can be learned at three schools:

- the SUIS (соёлын урлагын их сургууль), engl. "university of arts and culture" Here students enter in adult age for obtaining a bachelor's degree after 2 years and a master's degree after 5 years of musical education After the master's degree the students are considered to be professional musicians, and can play at one of the state ensembles or later become a teacher at the SUIS.

- the music and dance college (хөгжим бүгжийм kоллеж) Here usually children enter this school, which has a strong focus on music, but not exclusively

- the culture school of the SUIS (СУИСы, соёлын сургууль) Here several qualification courses are available. Graduates from this school mostly become teachers or enter the SUIS

Also many amateur players acquired reasonable skills by taking lessons from private teachers, or being taught by their parents or other relatives.

Cultural influence

The morin khuur is the national instrument in Mongolia. Many festivals are held for celebrating the importance of this instrument on the Mongolian culture, like the biannual "International Morin Huur Festival and competition", which is organized by the "World Morinhuur Association". First held in 2008, second in 2010 - with 8 participating countries (Mongolia, Korea, China, Russia, USA, Germany, France, Japan) - and planned for May 2012. Here many amateurs come and play freestyle pieces, but also a professional contest is held and an instrument making competition.

During June the "roaring hooves" festival is held. This is a small festival for professional skilled players - but unfortunately a closed festival. These recordings are often shown in TV reports later.

On the national festival "Naadam" praise songs are played for the most magnificent horse and for the highest ranked wrestler and archer. The songs are called "Magtaal" and accompanied by a unique style of praise and morin khuur.

Also many Mongolians have an instrument in their home, because it is a symbol for peace and happiness.

During the winter time, but also in beginning of the spring time a morin khuur player is called in for the "жавар үргээх", the "ceremony for scaring away the frost". In general many traditional pieces are played, divided in the different styles: "уртын дуу", "urtiin duu" (long song), "магтаал", "magtaal" (praise songs) and "татлага", "tatlaga" (solo pieces, mostly imitiating horses or camels).

The fourth style, the "биелгее" is rarely played in these ceremonies, but in western Mongolia it is common for accompanying "tatlaga dancing" in 3 times - like a waltz, but with dance movements imitating daily tasks of a nomad's family.

Gobi farmers animal psychology healing use

In the Mongolian Gobi farmer's daily life the Morin Khuur has another important use. When a mother camel gives birth to a calf sometimes it rejects her calf due to various natural stress situations and Mongolian camel farmers use Morin Khuur-based melodies alongside special low harmonic types of songs called "Khoosloh" to heal mother camels' stress and encourage it to re-adopt its calf. This re-adoption of farm animal practice is widely used in various nomadic civilizations worldwide but for Mongolian Gobi farmers' cases, only this instrument is used on camels. In other cases if a mother camel dies after giving birth to a calf, a farmer would use this Khoosloh technique alongside Morin Khuur melodies to encourage another mother camel who has its own calf to adopt the new one. The practice is well documented on documentary called Ingen Egshig directed by Badraa J. in 1986[4] and was also remade in 2003 by director Byambasuren Davaa with a different title of The Story of the Weeping Camel which nominated for 2005 Academy Award for Best Documentary.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Монгол ардын хөгжмийн зэмсэг. Accessed 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Morin khuur". www.silkroadproject.org. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ CD booklet notes, Mongolia: Traditional Music, 1991, Auvidis-UNESCO D 8207

- ↑ ACCU - UNESCO: Tol Avahuulah Aya 1986

- ↑ 77th Academy Awards

- Marsh, Peter K. (2004). Horse-Head Fiddle and the Cosmopolitan Reimagination of Mongolia. ISBN 0-415-97156-X.

- Santaro, Mikhail (1999). Морин Хуур - Хялгасны эзэрхийгч, available in cyrillic (ISBN 99929-5-015-3) and classical Mongolian script (ISBN 7-80506-802-X)

- Luvsannorov, Erdenechimeg (2003) Морин Хуурын арга билгийн арванхоёр эгшиглэн, ISBN 99929-56-87-9

- Pegg, Carole (2003) Mongolian Music, Dance, and Oral Narrative: Recovering Performance Traditions (with audio CD) ISBN 978-0-295-98112-3

External links

- Mongolian art and culture traditional instruments

- Embassy of Mongolia Seoul Mongolian culture, including the morin khuur.

- Music Tales Mongolian culture, introduction into the principles of Mongolian lyrics and to Mongolian folk songs

- Playing Chuurqin (solo 5:58~15:37) (accompaniment 15:37~18:49)

- A typical Chuurqin

- Chuur huur folk song (seems a variant, but not the Xinagan Chuur variant)

- The relation between Morin huur and Chuurqin

- Mu. Burenchugula's Harchin epic «Manggusuyin Wulige'er» (evil's story) play with a Morin huur's Chuur method playing