Music of Cornwall

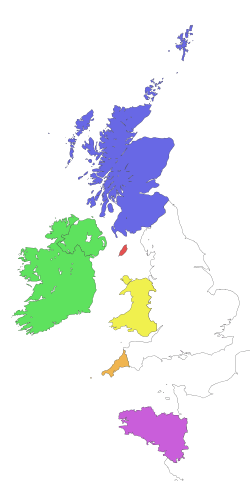

Cornwall is a culturally Celtic nation, though Celtic-derived musical traditions had been moribund for some time before being revived during a late-20th-century roots revival.

History

In medieval Cornwall there are records of performances of ‘Miracle Plays’ in the Cornish language, with considerable musical involvement. Also (as frequently mentioned in the Launceston borough accounts) minstrels were hired to play for saints day celebrations. The richest families (including Arundell, Bodrugan, Bottreaux, Grenville, and Edgcumbe) retained their own minstrels, and many others employed minstrels on a casual basis. There were vigorous traditions of Morris dancing, mumming, guising, and social dance.[1]

Then followed a long period of contention which included the Cornish Rebellion of 1497, the 1549 Prayer Book Rebellion, the Persecution of Recusants, the Poor Laws, and the English Civil War and Commonwealth (1642–1660). The consequences of these events disadvantaged many gentry who had previously employed their own minstrels or patronised itinerant performers. Over the same period in art music the use of modes was largely supplanted by use of major and minor keys. Altogether it was an extended cultural revolution, and it is unlikely that there were not musical casualties.[2]

18th and 19th centuries

However, a number of manuscripts of dance music from the period 1750 to 1850 have now been found which tell of renewed patronage, employment of dancing masters, and a repertoire that spanned class barriers. Seasonal and community festivals, mumming and guising all flourished.[3]

In the 19th century, the nonconformist and temperance movements were strong: these frowned on dancing and music, encouraged the demise of many customs, but fostered the choral and brass band traditions. Some traditional tunes were used for hymns and carols. Church Feast Days and Sunday School treats were widespread—a whole village processing behind a band of musicians leading them to a picnic site, where "Tea Treat Buns" (made with smuggled saffron) were distributed. This left a legacy of marches and polkas. Records exist of dancing in farmhouse kitchens, and in fish cellars Cornish ceilidhs called troyls were common, they are analogous to the fest-noz of the Bretons. Some community events survived, such as at Padstow and at Helston, where to this day, on 8 May, the townspeople dance the Furry Dance through the streets, in and out of shops, even through private houses. Thousands converge on Helston to witness the spectacle.[4] The "Sans Day Carol" or "St Day Carol" is one of the many Cornish Christmas carols written in the 19th century. This carol and its melody were first transcribed from the singing of a villager in St Day in the parish of Gwennap: the lyrics are similar to those of "The Holly and the Ivy".

In Anglican churches the church bands (a few local musicians providing accompaniment in services) were replaced by keyboard instruments (harmonium, piano or organ) and singing in unison became more usual.

Vocal music

Folk songs include "Sweet Nightingale", "Little Eyes", and "Lamorna". Few traditional Cornish lyrics survived the decline of the language. In some cases lyrics of common English songs became attached to older Cornish tunes. Some folk tunes have Cornish lyrics written since the language revival of the 1920s. Sport has also been an outlet for many Cornish folk songs, and Trelawny, the unofficial Cornish national anthem, is often sung by Cornish rugby fans, along with other favourites such as "Camborne Hill" and "The White Rose". The Cornish anthem that has been used by Gorseth Kernow for the last 75 plus years is "Bro Goth Agan Tasow"[5] ("The Land of My Fathers", or, literally, "Old Country of our Fathers") with a similar tune to the Welsh national anthem ("Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau") and the Breton national anthem ("Bro Gozh ma Zadoù"). "Bro Goth Agan Tasow" is not heard so often, as it is sung in Cornish. Another popular Cornish anthem is "Hail to the Homeland".

Sabine Baring-Gould compiled Songs of the West, which contains folk songs from Devon and Cornwall, in collaboration with Henry Fleetwood Sheppard and F. W. Bussell. Songs of the West was published by Methuen in conjunction with Watey and Willis; the first edition appeared both as a four-part set, undated, and as one volume dated 1895. In a new edition songs omitted from the first edition were listed, and the music was edited by Cecil Sharp. The second edition mentions the third collaborator, the Rev. Dr. F. W. Bussell, a scholarly eccentric who later became Vice-President of Brasenose College, Oxford. Sheppard was Rector of Thurnscoe, Yorkshire, and his parochial duties limited the amount of time he could spend on the work. In Plymouth City Library are two manuscript volumes containing the material as collected, in all 202 songs with music. In the published work it was necessary to bowdlerise some songs so that the book would be acceptable to respectable Victorians.[6]

Dances

Cornish dances include community dances such a 'furry dances', social (set) dances, linear and circle dances originating in karoles and farandoles, and step dances - often competitive. Among the social dances is 'Joan Sanderson’, the cushion dance from the 19th century, but with 17th-century origins.[7]

Breton connection

Cornish music is often noted for its similarity to that of Brittany; some older songs and carols share the same root as Breton tunes. From Cornwall, Brittany was more easily accessible than London. Breton and Cornish were (and are) mutually intelligible. There was much cultural and marital exchange between the two countries and this influenced both music and dance.[8]

Instrumentation

Cornish musicians have used a variety of traditional instruments. Documentary sources and Cornish iconography (as at Altarnun church on Bodmin Moor and St. Mary's, Launceston suggest a late-medieval line-up might include an early fiddle (crowd), bombarde (horn-pipe), bagpipes and harp. The crowdy crawn and fiddle (crowd in Cornish) were popular by the 19th century. In the 1920s there was a serious school of banjo playing in Cornwall. After 1945 accordions became progressively more popular, before being joined by the instruments of the 1980s folk revival. In recent years Cornish bagpipes have enjoyed a progressive revival.

Modern scene

Modern Cornish musicians include the late Brenda Wootton (folksinger in Cornish and English), the Cornish-Breton family band Anao Atao, the late 1960s band The Onyx and the 1980s band Bucca. Recently bands Sacred Turf, Skwardya and Krena, have begun performing electric folk in the Cornish language.[9]

Kyt Le Nen Davey, a multi-instrumental Cornish musician, established a not-for-profit collaborative organisation, Kesson, to distribute Cornish music to a world audience. Today, the site has moved with the times, and now provides individual track downloads, alongside traditional CD format.

Pioneering Techno artist Richard D. James (aka Aphex Twin) is a contemporary Cornish musician, frequently naming tracks in the Cornish language. Along with friend and collaborator Luke Vibert and business partner Grant Wilson-Claridge, James has crafted a niche of 'Cornish Acid' affectionately identified with his home region.

Bands such as Dalla and Sowena are associated with the noz lowen style of Cornish dance and music, which follows the Breton style of uncalled line dances. Troyls, usually called in a ceilidh style, occur across Cornwall with bands including the North Cornwall Ceilidh Band, The Brim, the Bolingey Troyl band, Hevva, Ros Keltek and Tros an Treys.Skwardya and Krena play rock, punk and garage music in the Cornish language. The Cornwall Songwriters organisation has since 2001 produced two folk operas 'The Cry of Tin' and 'Unsung Heroes'. Also Cornwall has a selection of up and coming young bands such as "Heart in One Hand" and "The small print".

3 Daft Monkeys (Tim Ashton, Athene Roberts, and Jamie Waters) combine vocals, fiddle, 12-string guitar, bass guitar and foot drum to play a fusion of Celtic, Balkan, Gypsy, Latino, dance, dub, punk, reggae and traditional folk music. The band have played at venues and festivals all over the UK and Europe, including Eden Project, the 2008 BBC Proms, Guilfest, Glastonbury Festival and the Beautiful Days festival, as well as supporting The Levellers.

Crowns are a 'fish-punk' band originating from Launceston, playing a mix of traditional Cornish songs and their own compositions. They have played Reading and Leeds festivals, the Eden Sessions and gained support slots with The Pogues, Blink 182 and Brandon Flowers. Their music has featured on Radio 1 and XFm.

The underground scene includes rappers Hedluv + Passman, multi-instrumentalist Julian Gaskell and alternative folk/skiffle duo Zapoppin’.

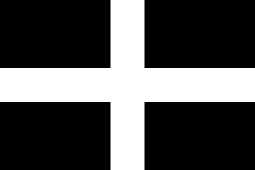

Sic, the singer of the Dutch pagan folk band Omnia hails from Cornwall and wrote a song named Cornwall about his homeland. During gigs by Omnia the Cornish flag is displayed on stage when this song is performed.

In 2012 the folksinger and writer Anna Clifford-Tait released 'Sorrow', a song written in Cornish and English.[10]

The Cornwall Folk Festival has been held annually for more than three decades and in 2008 was staged at Wadebridge.[11] Other festivals are the pan-Celtic Lowender Peran[12] and midsummer festival Golowan. Cornwall won the PanCeltic Song Contest[13] three years in a row between 2003 and 2005.[14]

The Welsh musician Gwenno Saunders has written and recorded songs in Cornish, notably Amser on her 2014 album Y Dydd Olaf.

Brass and silver bands

Lanner and District Silver Band is a Cornish Brass band based in Lanner, Cornwall, United Kingdom, and well known for its concerts. There are many other brass and silver bands in Cornwall, particularly in the former mining areas: St Dennis and Camborne are notable examples. There is a log of over 100 Brass Bands in Cornwall that are now extinct.[15]

Classical music

Triggshire Wind Orchestra, an amateur orchestra for wind players primarily from Sir James Smith's School, Wadebridge School, Budehaven Community School, was set up in 1984. After the success of the wind orchestra, Triggshire String Orchestra was set up, to cater for the string players from these schools.[16]

Cornish music and language radio

Cornish music radio can be found on Radyo an Gernewegva and features such artists as Dalla, Bagas Degol, Cam Kernewek, Leski, Ahanan, Julie Elwin, Phil Knight, Ryb an Gwella, Sowena, Captain Kernow and the Jack and Jenny Band, Quylkyn Tew, Gwenno, Skwardya and Trev Lawrence.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Hays, R. & McGee, C.; Joyce, S. & Newlyn, E. eds. (1999) Records of Early English Drama; Dorset & Cornwall Toronto: U.P.

- ↑ O'Connor, M. J. (2005) Ilow Kernow; 3 St Ervan: Lyngham House

- ↑ O'Connor, M. J. (2007) "An Overview of Recent Discoveries in Cornish Music", in: "Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall". Truro: R. I. C.

- ↑ "Helston, Home of the Furry Dance". Borough of Helston.

- ↑ Bro Goth Agan Tasow

- ↑ Purcell, William (1957) Onward Christian Soldier. London: Longmans, Green; pp. 145-48

- ↑ "Cornish Dancing". An Daras.

- ↑ Mathieson, K., ed. (2001) Celtic Music. San Francisco: Backbeat Books; pp 88-95

- ↑ Harvey, D. (2002) Celtic Geographies: old culture, new times. Routledge, pp. 223-24

- ↑ Anna Clifford-Tait recording 'Sorrow'

- ↑ Cornwall Folk Festival

- ↑ Lowender Peran

- ↑ Pan Celtic music festival

- ↑ Krena perform the PanCeltic 2005 winning song 'Fordh dhe Dalvann'

- ↑ Brush, John. "Cornwall Brass Bands". Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ "Concert by Triggshire String Orchestra". Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ Radyo an Gernewegva

- Graves, Alfred Perceval (1928). The Celtic Song Book: Being Representative Folk Songs of the Six Celtic Nations. London: Ernest Benn. (Available online on Digital Book Index)

Further reading

- Kennedy, Peter, ed. (1975) Folksongs of Britain and Ireland; edited by Peter Kennedy, et al. V: Songs in Cornish: (introduction; songs 85-96; bibliography). London: Oak Publications (pp. 203–44: the bibliography is very detailed and the songs have their airs)

External links

- Cornwall Council's music service delivering music tuition to schools and leading the Cornwall Music Hub

- Cornwall Music Education HUB - Led by Cornwall Council's Cornwall Learning

- Cornish music on www.kesson.com

- Cornish music from Top of the Hill Recordings on www.cornishmusic.com

- Cornish music from Top of the Hill Recordings on myspace

- 'The Cornish musicians collaborative' distributes Cornish musicians albums and provides online database of *Cornish bands and albums

- Record label, Top of the Hill Recordings promotes Cornish music and Musicians

- The Cornwall Fiddle Orchestra are a large group of string players led by fiddle player Hudson Swan and perform a repertoire of mainly traditional fiddle tunes from the Celtic nations including some dance tunes from Cornwall - www.myspace.com/heartinonehand

- Free sheet music from Cornwall (Creative commons and public domain)