Muted group theory

Muted group theory (MGT) is developed by social anthropologists Edwin Ardener and Shirley Ardener in 1975. The theory describes the relationship between a dominant group and its subordinate group(s): As the dominant group contributes mostly to the formulation of the language system, including the norms and vocabulary, members from the subordinate group have to learn and use the dominant-made language to express themselves. However, this translation process may result in loss and distortion of information as the people from subordinate groups cannot articulate their ideas clearly. The dominant may also ignore the voice of the lower-power. All these may eventually lead to the mutedness of the subordinate group. Although this theory is initially developed to study the different situations faced by women and men, it can also be applied to any marginalized group that is muted by the inadequacies of their languages.

There are three basic assumptions which are central to MGT: 1) The different experiences caused by the division of labor result in the different perceptions that women and men hold towards the world. 2) Women find it difficult to articulate their ideas as men's experience are dominant. 3) Women have to go through a translation process when speaking in order to participate in social life.

The study of MGT also offers resolution to change the muting status quo, i.e., naming the strategies of silencing, reclaiming, elevating and celebrating women's discourse, and creating new languages based on the experience of the marginalized group.

Overview

Origin

The Muted Group Theory was firstly developed in the field of cultural anthropology by the British Anthropologist Edwin Ardener. The first formulation of the Muted Group Theory emerges from one of Edwin Ardener's short essays, entitled "Belief and the Problem of Women", in which Ardener explored the "problem" of women. In social anthropology, the problem of women is divided in two parts: technical and analytical. The technical problem is that although half of the population and society is technically made up of women, ethnographers have often ignored this half of the population. Ardener writes that "those trained in ethnography evidently have a bias towards the kinds of model that men are ready to provide (or to concur in) rather than towards any that women might provide".[1] He also suggests that the reason behind this is that men tend to give a "bounded model of society"[1] akin to the ones that ethnographers are attracted to.[1] Therefore, men are those who produce and control symbolic production in a society. This leads to the analytical part of the problem which attempts to answer the question: "[…] if the models of society made by most ethnographers tend to be models derived from the male portion of that society, how does the symbolic weight of the other mass of persons express itself?".[1]

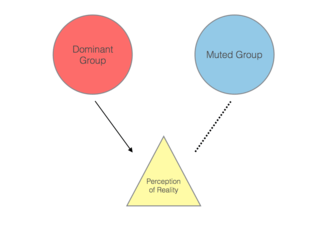

After conducting an experiment with the information in his essay, the results showed, while not fully proven, that the male point of view in society is the norm or dominant, which is why it is depicted with a standard solid line in this graph. On the other hand, female point of view is considered as non-dominant and non-standard, so it falls in the muted category with the broken line. According to Ardener, because male-based understanding of society represents the dominant worldview, certain groups get silenced or muted and they are not able to fully incorporate their experiences in such dominant structures of society. He thus writes: "In these terms if the male perception yields a dominant structure, the female one is a muted structure".[1] As part of the critical approach to the world, Ardener applies MGT to explore the power and societal structure in relation to the dynamism between dominant and subordinated groups. Moreover, Ardener's concept of muted groups does not only apply to women but can be applied to other non-dominant groups within societal structures.

Key concepts

Mutedness

Mutedness doesn't equal to silence. We call it "mutedness" when people cannot articulate their ideas regardless of time and space, without changing their language to meet the dominant group's vocabulary. Mutedness results from the lack of power and might lead to being overlooked, muffled, and invisible.[2] As Cheris Kramarae states, social interaction and communication create the current language structure. Because the latter was mainly built by men, men have an advantage over women. Consequently, women cannot express their thoughts through their own words because their language use is limited by the rules of a man's language.[3] Kramarae states, "The language of a particular culture does not serve all its speakers equally, for not all speakers contribute in an equal fashion to its formulation. Women (as well as members of other non-dominant groups) are not as free or as able as men are to say what they wish, because the words and the norms for their use have been formulated by the dominant group, men". As Cowan points out, "'mutedness' does not refer to the absence of voice but to a kind of distortion where subordinate voices…are allowed to speak but only in the confines of the dominant communication system".[4]

Muted group

Muted group or subordinated group is relative to the dominant group. According to Gerdrin, muting or silencing is a social phenomenon based on the tacit understanding that within a society there are dominant and non-dominant groups.[5] Thus, the muting process is a socially shared phenomenon that presupposes a collective understanding of who is in power and who is not.[5] The discrepancies in power result in the "oppressor" and "the oppressed". Kramarae points out that muted group as "the oppessed" are people who don't have a "publlic recognized volcabulary" to express their experience. Their failure in articulate their ideas lead to their doubt about "the validity of their experience" and "the legitimacy of their feelings".[2] Kramarae also addresses that gender, race, and class hierarchies, where muted groups, are supported by our "political, educational, religious, legal, and media systems".[2] Due to the lack of power, muted groups are usually at the margin of the society.

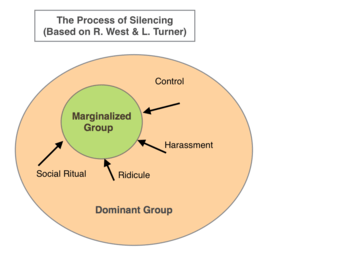

The "muting" process

Several scholars have researched and studied how the "muting" process occurs. Houston and Kramarae posit that women have been silenced in many ways by for example ridiculing women's related lexicon, reinforcing family hierarchies, constructing a male-controlled media, trivializing their opinions, ideas, and concerns, and censoring women's voices.[6] A central factor that contributes to these silencing methods is the trivialization of the lexicon and speech patterns that is often used to describe female activities e.g. with expressions such as chattering, gossiping, nagging, whining, bitching .[6]

According to West and Turner (2010), here are strategies to avoid the "Muting" process:

- Name the silencing factors, had it been men or news agencies.

- Reclaim, elevate and celebrate women's discourse.

- Create new words to the language system that are inclusive of marginalized groups and gendered words and experiences.

- Use media platforms (traditional and new) to voice groups.[7]

Assumptions

Assumption #1: The different experiences caused by the division of labor result in the different perceptions that women and men hold towards the world.

Using men's words is a disadvantage to women because Kramarae believes that men and women are vastly different and thus will view the world differently from men. This stems from the distinction between the meanings of the words "sex" and "gender". Kramerae believes that communication between men and women is not on an even level. This is because language is man made. This makes it easier for men to communicate over women. The Symbolic Interactionism Theory believes that "the extent of knowing is the extent of naming" (pg 462). When applying this to muted group, this means women have an extreme disadvantage over men because men are the namers.

Assumption #2: Women find it difficult to articulate their ideas as men's experience are dominant.

Kramarae argues that English is a "[hu]man-made language" and that it "embodies the perspectives of the masculine more than the feminine", while supporting "the perceptions of white middle-class males. Men are the standard".[8] In other words, Kramerae argues that men use language to dominate women, so that women's voices become less present, or "muted". Kramarae also explains that men's control over language has produced an abundance of derogatory words for women and their speech patterns. Some of these include names such as slut, whore, easy lay along with speech patterns such as gossiping, whining, and bitching.[6] However, there are much fewer names to describe themselves and most of them are seen in a positive/sexual light. These include words such as stud, player, and pimp (p. 465). Kramarae suggests these harmful words shape our reality. She believes that "words constantly ignored may eventually come to be unspoken and perhaps even unthought". This can lead women to doubt themselves and the intentions of their feelings (p. 465). Women are at a disadvantage once again.

Assumption #3: Women have to go through a translation process when speaking in order to participate in social life.

Kramarae also says that women need to choose their words carefully in public. This is because according to Kramarae "what women want to say and can say best cannot be said easily because the language template is not of their own making" (p. 459). Another example of this male-dominated language Kramarae brings up is that in public speaking, women most often use sports and war analogies (things most women do not usually associate themselves to) in order to relate to their male audiences. This stems from the market being dominated by males for so long. Almost all prominent authors, theorists, and scientists have historically been male. This allows for them to give women the "facts" they should believe about society and life in general.[9] Kramarae also believes that "males have more difficulty than females in understanding what members of the other gender mean". Dale Spender of Woman's Studies International Quarterly gave insight into Kramarae's statement by adding the idea that many men realize by listening to women they would be revoking some of their power and privileges. "The crucial issue here is that if women cease to be muted, men cease to be so dominant and to some males this may seem unfair because it represents a loss of rights". A man can easily avoid this issue by simply stating "I'll never understand women" (p. 461).

Extension of MGT

Although the muted group theory has been mainly developed as a feminist theory, it can also be applied to other silenced groups in society.[10] Mark Orbe, a communication theorist, has suggested that in the U.S. the dominant group consists of white, heterosexual, middle-class, males. Thus, groups that distinguish themselves from the dominant one in terms of race, age, gender, sexual orientation, and economic status can potentially be silenced or muted. In African-American communication research: Toward a deeper understanding of interethnic communication (1995) and Constructing co-cultural theory: An explication of culture, power, and communication (1998), Orbe fleshed out two important extensions of muted group theory:

- Muting as described in muted group theory can be applied to many cultural groups. Orbe stated that research performed by the dominant white European culture has created a view of African-American communication "which promotes the illusion that all African-Americans, regardless of gender, age, class, or sexual orientation, communicate in a similar manner".[11]

- There are several ways in which members of a muted group can face their position within the dominant culture. Orbe identified 26 different ways that members of muted groups can use to face the structures and messages imposed by dominant groups. For example, individuals can choose to (1) emphasize commonalities and downplay cultural differences, (2) educate others about norms of the muted group, and (3) avoid members of the dominant group. Orbe also suggests that individuals choose one of the 26 different ways based on previous experiences, context, abilities, and perceived costs and rewards.

Therefore, although Kramarae focuses on women's muted voices, she also opens the door to the application of muted group theory to issues beyond gender differences. Orbe, however, not only applies this theoretical framework to a different muted groups i.e. African-Americans, but also contributes by assessing "how individual and small collectives work together to negotiate their muted group status".[12][13] Further, although various groups can be considered as muted within society, silenced and dominant groups can also exist within any group. For example, Anita Taylor and M. J. Hardman posit that feminist movements can also present dominant subgroups that mute other groups within the same movement. Thus, members within oppressed groups can have diverse opinions and one can become dominant and further mute the others. [14]

Applications

Application in language

.jpg)

According to Kissack, traditionally communication has been constructed within the framework of a male dominated society. Women in corporate organizations are expected to use language associated with women, that is, "female-preferential" language. It has been considered as lower than the "male-preferential" language. The primary difference between the two is "male-preferential" language consists of details such as opinions and facts whereas "female-preferential" language consists mainly of personal details, emotions reflected in the conversations, also there is a great use of adjectives in it.[15]

Muted group theory has "recognized that women's voices are muted in Western society so that their experiences are not fully represented in language and has argued that women's experiences merit linguistic recognition".[16] Kramarae states that in order to change muted group status we also need to change dictionaries. Traditional dictionaries rely on the majority of their information to come from male literary sources. These male sources have the power to exclude words important to or created by women. Furthering this idea, Kramarae and Paula Treichler created A Feminist Dictionary with words they believed Merriam-Webster defined on male ideas. For example, the word "Cuckold" is defined as "the husband of an unfaithful wife" in Merriam Webster. However, there is no term for a wife who has an unfaithful husband. She is simply called a wife. Another example Kramarae defined was the word "doll". She defined "doll" as "a toy playmate given to, or made by children". Some adult males continue their childhood by labeling adult female companions "dolls". The feminist dictionary includes up to 2,500 words to emphasize women's linguistic ability and to give women words of empowerment and change their muted status.[17] Long argues that words can shape reality and feelings. She also believes that women can grab opportunities to take up physical and political space if they are given more verbal space.[18]

Application in mass media

According to Kramarae, women have been locked out of the publishing business until 1970; thus they lacked influence on mass media and have often been misrepresented in history. The reason behind this lies in the predominance of male gatekeepers, who are defined as editors and other arbiters of a culture who determine which books, essays, poetry, plays, film scripts, etc. will appear in the mass media.[19] Similarly, Pamela Creedon argues that in the mid-70s there is an increase of women in the male-dominated profession of journalism .[20]

In The Status of Women in the U.S. Media 2014, The Women's Media Centre researchers explore the current status of women in the mass media industry. The report compiles 27,000 pieces of content among "20 of the most widely circulated, read, and viewed, and listened TV networks, newspapers, news wires, and online news in the United States".[21] The results show that women (36.1%) are significantly out-numbered by men (63.4%). Although the number of women on TV news broadcasts is generally growing, the misrepresentation of women does not only regard their presence as anchors but also the events that they cover. Several studies show that while men mainly report on "hard" news, women are often relegated to cover "soft" news. Thus, women are often muted in terms of the topics they tend to cover.[22][23]

Although the Women's Media Centre study is very U.S.-centric, non-dominant groups are often muted even in other country's media landscapes. For example, Aparna Hebbani and Charise-Rose Wills have explored how Muslim women have often been muted in the Australian mass media sphere.[24] Their study shows that women that wear a hijab/burqa are often inaccurately and negatively connoted in Australian mass media.[24] According to the authors, Muslim women represent a muted group and thus cannot entirely incorporate their experiences, views, and perspective in their representation in Australian media. Thus, there is a social hierarchy that is privileging certain groups via Australian mass media.[24] It also shows that although currently muted, this group is attempting to gain a voice in this media landscape by engaging and interacting with members of the dominant culture in order to negotiate their silenced position.[24]

Application in social norms

There are some conventional stereotypes attached to men and women in society when an individual's behavior deviates from this norm they attain "negative feedback" for this opposition to the norm by their actions. In the case of women, this gets quite complicated as women are told to act in a certain manner, but when they do try and emulate their male counterparts, they are "discriminated" and "discouraged" for acting that way.[15]

Social rituals are another example of a place in which the muting process takes place. Kramarae suggests that many elements within wedding ceremonies place women in a silenced position. For example, the fact that the father of the bride "gives her away" to the groom, that the position of the bride – at the left of the minister – is considered less privileged than the one of the groom, that the groom announces his vows first, and that the groom is asked to kiss the bride, are all factors that contribute to the position of a woman as subordinated to the one of the man.[6]

As Catherine MacKinnon (one of the leading voices in the feminist legal movement ) suggests, the law sees women similarly as men see women. Like language, the legal system has thus been created, defined, and interpreted mostly by men.[25] In the context of unequal power relations between men and women, MacKinnon proposes new standards to define and evaluate sexual harassment and sex-related issues considered as the consequence of unwanted impositions of sexual requirements .[26] Finley argues that there has been a recent interest in feminist jurisprudence and legal scholarship inspired by the law's failure to see that despite the legal removal of barriers, sexes are not socially equal .[27]

Application in the workplace

.jpg)

In the western world women in the 1940s pursued jobs such as teaching in schools, hairdresser, and waitresses while men were at war. However, after the war period, the society did not encourage the participation of women in the workplace, and this way tried to assert male dominance in the society. Organizations till date appear to have a male dominance; the female experiences are at times not taken into account in the workplace the way the male experiences are, that is the "structure" is maintained by men who primarily use communication from the male perspective.[15]

Most of the goals of organizations are met by the usage of "male-preferential" language, as they tend to focus on aspects such as "economic gain" and "performance improved". The main point of an organizational communication is that it can help an employee male or female to fulfill their work duties and women are not able to achieve this using language more relevant to them, so in order to attain success in their workplace they have to go beyond their natural realm and utilize "male-preferential" language.[15]

One of the ways that women are differentiated can be observed when we take the "performance appraisals" into consideration. What they mainly consist of is reviews that are based on the standards that are more like "masculine" standards.[15] Another issue with women in the workplace is sexual harassment. Many women have a hard time when faced with harassment in a male dominated workplace because they are "the verbal minority".[28]

Application in education

.jpg)

Female students encounter a number of problems with respect to "reporting" their troubles such as "sexual harassment","poor advising" and not much encouragement towards the field of learning.[29] Kramarae has raised several thoughts provoking ideas such as the thought of education including ways to incorporate elements such as "women's humor", "speechlessness", and ways to address the issue of "abusive language".[29]

In the realm of a classroom men and women utilize language quite differently, the way they bond within their own sex is quite different when we compare the styles of both men and women. Women tend to bond with each other through the process of discussing their problems on the other hand men bond with each other with "playful insults" and "put downs".[30] In the event of classroom discussions, men tend to believe that they are supposed to dominate the class discussion while women avoid dominating the discussions.[30]

Houston believes in order to create a positive reform in education it might be useful to revise the curriculum and lay special stress on "woman-centered communication" education. "Women's studies" (WS) have been evolving and growing through the ages, today there is greater demand for faculty to be on initiatives such as WS programs, and the "African American programs".[29]

Application in politics

.jpg)

Independent parties have emerged since World War II to offer people alternative choices for election. However, most of these parties operate only in "circumscribed regions or with very narrow platforms". Prentice studied the impact of the third party, i.e., candidates from non-major parties, in public debate. He finds out that there have been few studies around third party by 2003 and even though third party candidates are involved in public campaign debates, they remain inarticulate and ignored due to the judgment by "standard of the political rhetoric and worldview of the major parties".[31]

Prentice points out that major parties usually interfere the free expression of third party through three ways: "ignore their claims, appearing confused (verbally or nonverbally) by the claims or actively attacking the claims made". He also notices that the debate questions are put in a way that reflects major parties' worldviews, which results in third party's mutedness. In order to participate and articulate their own worldview, third party candidates have to transform their ideas to match the major parties' models through emphasizing the agreements with the majority rather than the differences and sometimes may lead them to make statements that can be misinterpreted.[31]

Application in LGBT study

LGBT groups are considered marginalized and muted in our society.[32] The dominant groups who "hold privileged positions within society" have developed social norms and marginalized the minority groups such as LGBT groups.[33] Although the LGBT individuals don't necessarily share the same identity, they share the same experience of being marginalized by the dominant groups. As Gross notes, "For many oppressed groups the experience of commonality is largely the commonality of their difference from, and oppression by, the dominant culture".[34] In order to function and achieve success within the dominant culture, LGBT groups must adopt certain communication strategies to match the social norms.[35]

Orbe regards "interactions among underrepresented and dominant group members" to be co-cultural communication. He argues that there are three preferred outcomes in the co-cultural communication process: "assimilation (e.g., becoming integrated into mainstream culture), accommodation (gaining acceptance and space in a society and achieving cultural pluralism without hierarchy), or separation (maintaining a culturally distinct identity in intercultural interactions" and three communication approaches: "nonassertive (when individuals are constrained and nonconfrontational, putting the needs of others first to avoid conflicts), assertive (when individuals express feelings, ideas, and rights in ways that consider the needs of themselves and others), or aggressive (when individuals express feelings, ideas, and rights in ways that ignore the needs of others)". The different combinations of the three preferred outcomes and three communication approaches result in nine communication orientations.[36]

Application in race

.jpg)

Gloria Ladson-Billings believes that "stories provide the necessary context for understanding, feeling, and interpreting" and argues that voices of dispossessed and marginalized groups such as people of color are muted within the dominant culture.[37] Critical race theorists try to bring the minority's viewpoints to the forefront through an encouragement of "naming one's own reality". Delgado addresses three reasons for "naming one's own reality" in legal discourse: "1)much of 'reality' is socially constructed; 2) stories provide members of outgroups a vehicle for psychic self-preservation; and 3) the exchange of stories from teller to listener can help overcome ethnocentrism and the dysconscious drive or need to view the world in one way".[38]

When it comes to education, critical race theorists argue that the official school curriculum is designed to maintain a "White supremacist master script". As Swartz contends, master scripting sets the standard knowledge for students, which legitimizes "dominant, white, upper-class, male voices" and mutes multiple perspectives. The voices from other non-dominant groups are under control, mastered and can only be heard through reshaping and translation to meet the dominant standard.[39] Therefore, Lasdon-Billing argues that the curriculum should be race-neutral or colorblind, present people of color, and "presume a homogenized 'we' in a celebration of diversity".[37]

Critiques

Deborah Tannen the theorist that created Genderlect Theory criticizes feminist scholars like Kramarae for assuming that men are trying to control women. Tannen acknowledges that differences in male and female communication styles sometimes lead to imbalances of power, but unlike Kramarae, she is willing to assume that the problems are caused primarily by men's and women's different styles. Tannen warns readers that "bad feelings and imputation of bad motives or bad character can come about when there was no intention to dominate, to wield power".[40] Kramerae thinks Tannen's opinion is naïve. She believes men belittle and ignore women whenever they speak out against being muted. She also pointed out that "our political, educational, religious, legal, and media systems support gender, race, and class hierarchies".[41] Both theorists believe muting is involved, but they see it from different standpoints.

Edwin Ardener saw that muted group theory had pragmatic as well as analytical potentials.[42] Edwin Ardener always maintained that muted group theory was not only, or even primarily, about women - although women comprised a conspicuous case in point. In fact, he also drew on his personal experience as a sensitive (intellectual) boy among hearty (sportive) boys in an all boys London secondary school. As a result of his early encounters with boys, thereafter he identified with other groups in society for whom self-expression was constrained.[42]

Is muted group out dated? In the 1970s and 1980s, the muted group theory challenged the status quo, of academe at least. While many women reading and discussing the theory thought it made sense of their own lives, many other academics thought it wasn't proper—theoretically and politically. It certainly wasn't like any of the theories in introductory communication texts then. It was pretty radical. If the muted group theory now isn't as exciting as it once seemed, this is due in part to its success and the success of theories and actions related to it. Shirley and Edwin Ardener suggested that there are "dominant modes of expression in any society which have been generated by the dominant structure within it".[43] They wrote that women, due to their structural places in society, have different models of reality. Their perspectives are "muted" because they do not form part of the dominant communication system of the society.[44]

See also

There are many theories that appear to be related to the Muted Group Theory. These include but are not limited to: Spiral of Silence Theory (SST), Standpoint Feminism (SF), Standpoint Theory (ST), Groupthink Theory (GT), Co-cultural Theory (CT), Critical Race Theory (CRT), and Cultural Studies (CS).

Read More:

- Spiral of Silence Theory.

- Standpoint Feminism.

- Standpoint Theory.

- Groupthink Theory.

- Co-cultural Theory.

- Critical Race Theory.

- Cultural Studies.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ardener, Edwin, & Chapman, Malcolm. (2007). The voice of prophecy and other essays. New York: Berghahn Books.

- 1 2 3 Griffin, Emory A (2011). A First Look at Communication Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5.

- ↑ Kramarae, Cheris (1981). Women and men speaking: Frameworks for analysis. Newbury House Publishers. Rowley, MA: Print.

- ↑ Cowan, R. (May, 2007). Muted group theory: Providing answers and raising questions concerning workplace bullying. Conference Papers -- National Communication Association. Chicago, IL.

- 1 2 Gendrin, D. M. Homeless women's inner voices: Friends or foes?, in Hearing many voices. Hampton Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Houston, Marsha; Kramarae, Cheris (1991). "Speaking from silence:methods of silencing and of resistance". Discourse and society. 2.4 387-400. Print.

- ↑ West, Richard L., and Lynn H. Turner (2010). Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application. 5th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill. Web

- ↑ Littlejohn, S.W., & Foss, K.A. (2011). Theories of human communication, 10th ed. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. P148

- ↑ VanGorp, Ericka. "Muted Group Theory".

- ↑ Hechter, M. (2004). "From class to culture". The American Journal of Sociology. 110: 400–445. doi:10.1086/421357.

- ↑ Orbe, MP (1995). "African American Communication Research: Toward a Deeper Understanding of Interethnic Communication.". Western Journal of Communication. 59: 61–78. doi:10.1080/10570319509374507.

- ↑ Orbe, M. P. (1995). Continuing the legacy of theorizing from the margins: Conceptualizations of co-cultural theory", Women and Language. pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Orbe, M. P. (1998). "Explicating a co-cultural communication theoretical model", African American communication and identities: Essential reading. Thousand Oakes.

- ↑ Hardman, M. J.; Taylor, A. (2000). Hearing Many Voices. Hampton Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kissack, H. (2010). "Muted voices: a critical look at e-male in organizations". Journal of European Industrial Training. 34 (6): 539–551. doi:10.1108/03090591011061211.

- ↑ Wood, J. T. (2005). Feminist standpoint theory and muted group theory: Commonalities and divergences. Women & Language, 28(2), 61-64.

- ↑ Treichler, P., and C. Kramarae. (1985) A feminist dictionary. Boston. Print.

- ↑ Long, Hannah R. "Expanding the Dialogue: 7e Need for Fat Studies in Critical Intercultural Communication." (Winter 2015).

- ↑ Kramarae, Cheris. Technology and Women's Voices : Keeping in Touch.

- ↑ Creedon, P.; Cramer, J. (2007). Women in Mass Communication. Thousand Oak. pp. 275–283.

- ↑ "The Status of Women in the U.S. Media 2014". Women's Media Center.

- ↑ Grabe, Maria Elizabeth; Samson, Lelia (2012). "Sexual Cues Emanating From the Anchorette Chair: Implications for Perceived Professionalism, Fitness for Beat, and Memory for News". Communication Research. 38: 471–496. doi:10.1177/0093650210384986.

- ↑ Engstrom, Erika; Ferri, Anthony J (Fall 2000). "Looking Through a Gendered Lens: Local U.S. Television News Anchors' Perceived Career Barriers". Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media.

- 1 2 3 4 Hebbani, Aparna; Rose-Wills, Charise. "How Muslim women in Australia navigate through media (mis) representations of hijab/burqa". Australian Journal of Communication: 89–102.

- ↑ MacKinnon, Catherine A. (Summer 1983). "Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: Toward Feminist Jurisprudence". The University Chicago Press.

- ↑ MacKinnon, Catherine A. (1979). Sexual Harassment of Working Women. Yale University Press.

- ↑ Finley, L. (1988). "The nature of domination and the nature of women: reflections on Feminism Unmodified". Northwestern University Law Review.

- ↑ Wood, J. T. (1992). Telling our stories: Narratives as a basis for theorizing sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 20, 349-362.

- 1 2 3 Kramarae, Cheris. (1996) "Centers Of Change: An Introduction To Women's Own Communication Programs." Communication Education 45.4: 315. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 18 Nov. 2013.

- 1 2 Tannen, Deborah (1992). "How Men and Women Use Language Differently in Their Lives and in the Classroom". The Education Digest. 57 (6). n. page. Web. 19 Nov. 2013.

- 1 2 Prentice, Carolyn (2005). "Third Party Candidates in Political Debates: Muted Groups Struggling to Express Themselves". Speaker & Gavel. 42: Iss. 1, Article 2.

- ↑ Muñoz, J. E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of color and the performance of politics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- ↑ Orbe, M. P. (1996). Laying the foundation for co‐cultural communication theory: An inductive approach to studying "non‐dominant" communication strategies and the factors that influence them. Communication Studies, 47(3). doi: 10.1080/10510979609368473

- ↑ Gross, L. (1993). Contested closets: The politics and ethics of outing. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- ↑ Fox, J., & Warber, K. M. (2015). Queer identity management and political self-expression on social networking sites: A co-cultural approach to the spiral of silence. Journal of Communication, 65, 79-100.

- ↑ Orbe, M.P. (1998b). From the standpoint(s) of traditionally muted groups: Explicating a co-cultural communication theoretical model. Communication Theory, 8, 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1998.tb00209.x

- 1 2 Ladson-Billings, Gloria. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what's it doing in a nice field like education?, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11:1, 7-24, DOI: 10.1080/095183998236863

- ↑ Delgado, R. (1989). Symposium: Legal storytelling. Michigan Law Review, 87, 2073.

- ↑ Swartz, E. (1992). Emancipatory narratives: Rewriting the master script in the school curriculum. Journal of Negro Education, 61, 341-355.

- ↑ Tannen, Deborah (2005). Conversational style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Griffin, Em (2011). A First Look at Communication Theory. David Patterson. ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5.

- 1 2 Ardener, Shirley; Edwin Ardener (2005). ""Muted Groups": The genesis of an idea and its praxis.". Women and Language. 28 (2): 51.

- ↑ Ardener, E (1975). "Belief and the problem of women". In Ardener, Shirley. Perceiving women. London: Malaby Press.

- ↑ Kramarae, Cheris (2005). "Muted Group Theory and Communication: Asking Dangerous Questions". Women and Language. 28 (2): 56.