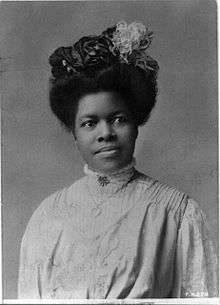

Nannie Helen Burroughs

Nannie Helen Burroughs, (May 2, 1878 – May 20, 1961) was an African-American educator, orator, religious leader, civil rights activist, feminist and businesswoman in the United States.[1] She gained national recognition for her 1900 speech "How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping," at the National Baptist Convention.

On October 19, 1909, she founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., which uniquely provided academic, religious and vocational classes for black girls and young women at a time when education was segregated in the South; she operated it until her death. It has since been renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor and provides coeducational classes for the elementary grades. Its Trades Hall, built in 1927-28, has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Early life and education

Nannie Helen Burroughs was born on May 2, 1878, in Orange, Virginia.[2] Her parents were John and Jennie Burroughs. Her father was born as a free person of color and her mother was born into slavery in Virginia, the daughter of a slave. John Burroughs attended the Richmond Institute and became a Baptist preacher. He was a farmer and served as an itinerant preacher. Her mother worked as a cook before and after the American Civil War.

In 1883, Jennie Burroughs moved with her daughter Nannie, then five, to Washington D.C. so that the girl could be educated in its city schools. Burroughs' parents were associated with a small and fortunate class of free blacks and ex-slaves who possessed the energy and ability to begin working towards prosperity almost as soon as they were freed by the American Civil War.

In 1902 Nannie Burroughs, already working, studied business. In 1907, she received an honorary A.M. degree from Eckstein-Norton University, a historically black college in Kentucky.[3]

Career

After the American Civil War, black congregations had quickly withdrawn from white-dominated churches in the South to create churches independent of white supervision. They had a few before the war, but soon had many more. Within several years, they were setting up state Baptist associations and, by the end of the 19th century, national associations. The National Baptist Convention is the largest black Baptist denomination. In addition, such independent denominations as the African Methodist Episcopal Church planted new congregations among black communities in the South.

In 1896, Burroughs helped establish the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), one of a number of new associations of black women organized for philanthropic and charitable purposes. In 1897, she started work as an associate editor at the Christian Banner in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1]

In 1898 Burroughs moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and began working as bookkeeper and editorial secretary for the Foreign Mission Board of the National Baptist Convention, where she served until 1909. This was the national association of black Baptist churches.

She gained national recognition for her 1900 speech "How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping," at the National Baptist Convention. In 1905 she drew international attention at the age of 19 for her speech "The Triumph of Truth at the first gathering of the Baptist World Alliance in London, to a crowd estimated at more than 10,000 people near the Marble Arch in Hyde Park.[4]

In 1909, Burroughs founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C.[5] The school emphasized preparing students for employment. Burroughs offered courses in domestic science and secretarial skills, but also in occupations such as shoe repair, barbering, and gardening. Burroughs created a creed of racial self-help through her program of the three Bs: the Bible, the bath, and the broom. That stood for a clean life, a clean body, and a clean house.[2] Burroughs was one of the first honorary members to be inducted into Delta Sigma Theta, a black sorority.

Burroughs believed domestic work should be professionalized and vocational. She trained her students to be become self-sufficient wage earners and expert homemakers. She emphasized the importance of being proud black women to all students, by teaching African-American history and culture through a required course in the Department of Negro History.[6]

Burroughs became active in the National League of Republican Colored Women, trying to influence the national party on behalf of African Americans. She also participated in the National Association of Wage Earners, working to influence legislation related to wages for domestic workers and other positions held by women.

She gained prominent supporters for her school; for instance, pastor Adam Clayton Powell, who led the large and influential Abyssinian Baptist Church of New York City, was on the board of trustees of the National Training School. He helped raise funds for construction in 1927-1928 of its Trades Hall building, which in 1991 was designated as a National Historic Landmark.[5][8] In 1934, the school was renamed the National Trades and Professional School for Women. The school was inactive for a time during the Great Depression but Burroughs revived it, and it has operated to the present day.

Burroughs also worked within the system. In 1928, the Herbert Hoover administration appointed Burroughs as committee chairwoman related to Negro Housing, for his 1931 White House Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership, soon after the Crash of 1929 as the Great Depression began.[9] In 1933, she spoke to the Virginia Women's Missionary Union at Richmond, with an address entitled "How White and Colored Women Can Cooperate in Buildin a Christian Civilization."[10]

Death and legacy

Burroughs died in Washington, D.C., on May 20, 1961, of natural causes. The funeral was held at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church where she was a member. The Library of Congress, Manuscript Division holds over 110,000 items in her papers.[3]

- 1907, she received an honorary M.A. from Eckstein Norton University, a historically black college in Cane Spring, Bullitt County, Kentucky. (It merged with Simpson University in 1912.)[11]

- In 1976, the school that Burrough had founded in Washington, DC in 1909 as the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC was renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor. Its Trades Hall has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.

- Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue NE, a street in the Deanwood neighborhood of Washington, DC, is named for her.

- In 1997 the National Women's History Project honored Burroughs during Women's History Month.[12]

References

- 1 2 "Nannie Helen Burroughs papers, 1900-1963 (Library of Congress), Biographical Note (Woman's Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention of the United States of America)". 2001 (last updated 2010 April). Retrieved 2010-10-27. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 "Nannie Lee Burroughs", Discovering Hidden Washington, Library of Congress Live, November 20, 2003.

- 1 2 "Education: African-American Schools, Nannie Helen Burroughs", American Memory: American Women, Library of Congress

- ↑ Frederick Jarrard Anderson, Hearts & Hands: Gathering up the Years: An Illustrated History of Woman's Missionary Union of Virginia 1874-1988 (William Byrd Press, 1990), p. 103

- 1 2 Page Putnam Miller (February 9, 1990). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Trades Hall of National Training School for Women and Girls / Nannie Helen Burroughs School" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying three photos, exterior, from 1989 (32 KB)

- ↑ "A True Girl-Friend, Nannie Burroughs", African-American Registry

- ↑ Taylor, Julius F. "The Broad Ax". Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "National Training School for Women and Girls". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ↑ 314 - "White House Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership", September 15, 1931, Herbert Hoover, American Presidency Project

- ↑ Anderson p. 103

- ↑ Runoko Rashidi & Karen A. Johnson, "A brief note on the lives of Anna Julia Cooper & Nannie Helen Burroughs: Profiles of African Women educators", Hartford, 1998 (revised December 19, 1999), Runoko Rashidi, accessed on December 18, 2007

- ↑ "Honorees: 2010 National Women's History Month". Women's History Month. National Women's History Project. 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- Encyclopedia of African -American Culture and History, 2006

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nannie Helen Burroughs |