Nauvoo Temple

| Nauvoo Temple | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destroyed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

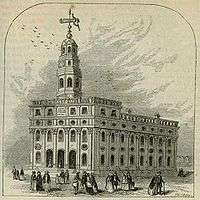

Undated photograph of the Nauvoo Temple. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dedication | 1 May 1846 by Orson Hyde | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Floor area | 54,000 sq ft (5,000 m2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Kirtland Temple | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official website• News & images | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 40°33′1.216800″N 91°23′2.972399″W / 40.55033800000°N 91.38415899972°W The Nauvoo Temple was the second temple constructed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.[2][3] The church's first temple was completed in Kirtland, Ohio, United States, in 1836. When the main body of the church was forced out of Nauvoo, Illinois, in the winter of 1846, the church attempted to sell the building, finally succeeding in 1848. The building was damaged by fire and a tornado before being demolished.

In 1937, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) reacquired the lot on which the original temple had stood. In 2000, the church began to build a temple on the original site whose exterior is a replica of the first temple, but whose interior is laid out like a modern Latter-day Saint temple. On 27 June 2002, a date that coincided with the 158th anniversary of the death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, the temple was dedicated by the LDS Church as the Nauvoo Illinois Temple.

History

The Latter Day Saints made preparations to build a temple soon after establishing their headquarters at Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1839. On 6 April 1841, the temple's cornerstone was laid under the direction of Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement and Sidney Rigdon gave the principal oration. At its base the building was 128 feet (39 m) long and 88 feet (27 m) wide with a clock tower and weather vane reaching to a total height of 165 feet (50 m)—a 60% increase over the dimensions of the Kirtland Temple. Like Kirtland, the Nauvoo Temple contained two assembly halls, one on the first floor and one on the second, called the lower and upper courts. Both had classrooms and offices in the attic. Unlike Kirtland, the Nauvoo Temple had a full basement which housed a baptismal font. Because the Saints had to abandon Nauvoo, the building was not entirely completed. The basement with its font was finished, as were the first floor assembly hall and the attic. When these parts of the building were completed they were used for performing ordinances (basement and attic) or for worship services (first floor assembly hall).

The Nauvoo Temple was designed in the Greek Revival style by architect William Weeks, under the direction of Joseph Smith. Weeks' design made use of distinctively Latter Day Saint motifs, including Sunstones, Moonstones, and Starstones. It is often mistakenly thought that these stones represent the Three Degrees of Glory in the Latter Day Saint conception of the afterlife, but the stones appear in the wrong order. Instead, Wandle Mace, foreman for the framework of the Nauvoo Temple, has explained that the design of the temple was meant to be “a representation of the Church, the Bride, the Lamb’s wife” (Wandle Mace, Autobiography 207 (BYU Special Collections)). In this regard Mace references John’s statement in Revelation 12:1 concerning the “woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars.” This explains why the Starstones are at the top of the temple (“crown of twelve stars”), the Sunstones in the middle (“clothed with the sun”) and the Moonstones at the bottom (“moon under her feet”).

Construction was only half complete at the Death of Joseph Smith in 1844. After a succession crisis, Brigham Young was sustained as the church's leader by the majority of Latter Day Saints in Nauvoo. As mob violence increased during the summer of 1845, he encouraged the Latter Day Saints to complete the temple even as they prepared to abandon the city, so portions of it could be used for Latter Day Saint ordinance, such as baptisms for the dead in the basement font. During the winter of 1845-46, the temple began to be used for additional ordinances, including the Nauvoo-era endowment, sealings in marriage, and adoptions. The Nauvoo Temple was in use for less than three months.

Most of the Latter Day Saints left Nauvoo, beginning in February 1846, but a small crew remained to finish the temple's first floor, so that it could be formally dedicated. Once the first floor was finished with pulpits and benches, the building was finally dedicated in private services on 30 April 1846, and in public services on 1 May. In September 1846 the remaining Latter Day Saints were driven from the city and vigilantes from the neighboring region, including Carthage, Illinois, entered the near-empty city and vandalized the temple.

Initially the church's agents tried to lease the structure, first to the Catholic Church, and then to private individuals. When this failed, they attempted to sell the temple, asking up to $200,000, but this effort also met with no success. On 11 March 1848, the LDS Church's agents sold the building to David T. LeBaron, for $5,000. Finally, the New York Home Missionary Society expressed interested in leasing the building as a school, but around midnight on 8–9 October 1848, the temple was set on fire by an unknown arsonist. Nauvoo's residents attempted to put out the fire, but the temple was gutted. James J. Strang, leader of the Strangite faction of Latter Day Saints, accused Young's agents of setting fire to the temple. However, Strang's charges were never proven. On 2 April 1849 LeBaron sold the damaged temple to Étienne Cabet for $2,000. Cabet, whose followers were called Icarians, hoped to establish Nauvoo as a communistic utopia.[4]

Destruction

After the fire of 9 October 1848, only the four exterior walls remained standing.[5] The Icarian leader Cabet was fascinated by the temple and planned to reconstruct it, and a considerable amount of money was spent in the endeavor. However, On 27 May 1850, Nauvoo was struck by a major tornado which toppled one of the walls of the temple. One source claimed the storm seemed to "single out the Temple", felling "the walls with a roar that was heard miles away".[6] Cabet ordered the demolition of two more walls in the interests of public safety, leaving only the façade standing. The Icarians used much of the temple's stone to build a new school building on the southwest corner of the temple lot. By 1857, however, most of Cabet's followers had left Nauvoo and over time many of the original stones for the temple were used in the construction of other buildings throughout Hancock County. In February 1865 Nauvoo's City Council ordered the final demolition of the last standing portion of the temple—one lone corner of the façade. Soon afterwards, all evidence of the temple disappeared, except for a hand pump over a well that supplied water to the baptismal font.[4] Three of the original sunstones are known to have survived and are on display — one is on loan to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' Visitor Center in Nauvoo, one is in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C, and the third and only one that has not been restored is displayed, along with the only moonstone on display, at the Joseph Smith Historic Center of the Community of Christ.

Nauvoo Illinois Temple

Between 1937 and 1962, the LDS Church reacquired and restored the lot on which the temple stood. In 1999, church president Gordon B. Hinckley announced the rebuilding of the temple on its original footprint. After two years of construction, on 27 June 2002, the church dedicated the Nauvoo Illinois Temple, whose exterior is a replica of the first temple, but whose interior is laid out like a modern LDS temple.

Architecture

At its base the Nauvoo Temple was 128 feet (39 m) long and 88 feet (27 m) wide with a tower and weather vane reaching to 65 feet (20 m). The second temple of the Latter Day Saint movement was built 60% larger in dimensions than its predecessor, the Kirtland Temple. Like Kirtland, the temple contained two assembly halls, one on the first floor and one on the second, called the lower and upper courts. Both had classrooms and offices in the attic. Unlike Kirtland, it had a full basement which housed a baptismal font.

Exterior

The limestone used for the original temple was quarried from a site just west of the temple. Much of that quarry, however, was submerged by rising water behind the Keokuk Dam in 1912. Therefore, Russellville, Alabama, subsidiary of Minnesota's Vetter Stone Company, was chosen by the Church to provide stone for the new temple. Church officials say the quarry was selected because it provided stone that is a close match to the limestone originally used.

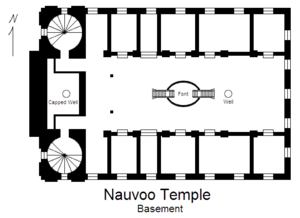

Basement

The basement of the Nauvoo Temple was used as the baptistry, containing a large baptismal font in the center of the main room.

The basement was reached from the spiral staircases at the northwest and southwest corners of the temple. The staircase landing was made of wood and opened to a short hallway heading East, leading to the basement proper. Between the two hallways was an unfinished room sealed off from the rest of the temple, containing an old well that had been dug but never used. The room was discovered by an anti-Mormon mob who broke through the floor of the vestibule above.[7]

The basement proper was one hundred feet long and forty feet wide with six rooms of varying sized on either side. The sides of the rooms were stone and abutted the massive stone piers that supported the floors above. With the exception of the two rooms at the West end of the basement, reportedly used for clerical purposes, each side room rose two steps in height from the basement floor. The rooms were dressing rooms for those using the font. The floor was made of red brick laid in a herringbone pattern. The walls were painted white. The floor sloped down to the center of the room to allow water to run toward a drain beneath the font.[7]

During an archaeological investigation of the temple site, two highly polished limestone blocks were discovered. Approximately twelve feet east of the entrance to the baptistry and ten feet from either the side of the support piers rested the blocks, roughly fourteen inches square, which projected seven inches (178 mm) above the brick floor. These objects are not mentioned in any account of the basement, and their purpose is unknown. They may have held some type of support columns, dividing the font from the entrance to the basement or they may have simply been a decorative element with a vase or something similar resting on them. They may have been part of a feature planned, but not used, in the final construction.[7]

The baptismal font

.jpg)

Every visitor who wrote about the temple mentioned the baptismal font. It was clearly the most impressive feature of the temple. There were actually two fonts built during the lifetime of the temple, a temporary wooden one, and a permanent limestone one.[7]

The first font was built out of tongue and grooved white pine and painted white. It was sixteen feet long, twelve feet wide and four feet deep. The lip of the font was seven feet from the floor. The font's cap and base were carved molding in an "antique style" and the sides were finished with panel work. Two railed stairways led to the font from the north and south sides.[7]

The font was held up by twelve oxen as are almost all temple fonts. They were carved from pine planking that was glued together. They were patterned from the most beautiful five-year-old steer that could be found in the region. The head, shoulders and legs protruded beyond the base of the font, and they appeared to have sunk to their knees into the pavement. The most perfect horn that could be found was used to model the animals horns.[7]

A decision was made to replace the wooden font in 1845, apparently because the water caused a mildew odor, and possibly because the wood began to rot. The new limestone font followed the pattern of the wooden one. Twelve oxen held up the basin, four on each side and two at each end. The oxen were solid stone and similarly were placed and appeared sunken into the floor. Where the oxen met the basin, the stone was carved to suggest drapery. The ears of the oxen were made of tin. The stairs were moved to an East/West orientation making access to the font easier.[7]

A well on the east side of the font provided the water supply. There may have been some kind of tank at the East end of the baptistry to store and heat water.[7]

The vestibule

A flight of eight broad steps led to a landing where two more steps entered three archways. These archways led to the vestibule, the formal entrance to the temple. The archways were approximately nine feet wide and twenty-one feet high.

The vestibule itself was forty-three feet by seventeen feet in dimension. It was composed of limestone on all four of its walls. The floor has been speculated to be made of wood, because when the mob occupied the temple briefly in late 1847, they broke through the floor to reach a sealed off room in the basement. Had the floor been limestone, it seems unlikely that they would have dug it up.

Two large double doors on the east wall opened to the first floor assembly hall of the lower court, known as the "Great Hall". Two doors, one on the North wall, and another on the South opened to the landing of two spiral staircases, one in the Northwest corner, and the other in the Southwest corner which led all the way to the attic. These were the only access points to the rest of the building.

One report stated that on the east wall of the vestibule was an entablature, similar to the one in the facade, which read in bright gilded letters, "THE HOUSE OF THE LORD - Built by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints - Commenced April 6th, 1841 - HOLINESS TO THE LORD."[7]

The stairwells

The two stairwells were constructed of dressed limestone walls. One rose from Northwest corner and the other at the Southwest corner of the temple. They were not true circles but were flatted on four sides. Nor were they symmetrical, being sixteen feet in diameter from East to West and seventeen feet in diameter from North to South. This was done to support landings and other support structures.[7]

The staircases, made of wood, provided access to all of the temple from the basement to the attic with a landing at each floor. They had lamps for illumination at night, and had windows for daytime illumination. William Weeks' elevation of the front facade does not show windows at the basement level of the two stairwells, and photographic evidence is inconclusive. However, Joseph Smith's youngest son, David Smith, rendered a painting of the temple's damaged facade, clearly shows half-circular windows at the basement level in the north and south corners of the facade.[7]

The staircase in the northwest corner was never completed. It was roughed in with temporary boards resting on the risers. Workmen used this staircase to gain access to the building during its construction, especially during the winter of 1845-1846 when persons were using the other staircase to reach the attic for ordinance work. The southwest staircase was completely finished for use. It included lamps for night illumination, and may have been carpeted near the attic landing.[7]

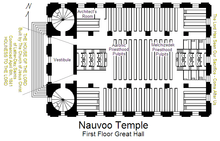

The Great Hall

Entrance to the first floor assembly hall, called the "Great Hall", was through two large double doors at the east end of the vestibule. The Great Hall occupied the remainder of the floor space East of the vestibule. The room was flanked on either side by seven large, arched windows, with four similar windows along the east wall. An arched ceiling spanned some fifty feet in breadth, in the center. the floor was stained wood and the walls were painted white.[7]

There were two rooms to the north just past the entrance. It has been suggested that these rooms were used initially by William Weeks, because they are referred by Thomas Bullock as the "architect's room." Their eventual intended use is not clear.[7]

Pulpits

At the East and West ends of the hall were two sets of similar pulpits. Resembling the pulpits used in the Kirtland Temple, and repeated in later temples, they were arranged with four levels, the top three consisting of a group of three semi-circular stands. The lowest level was a drop-table which was raised for use in the sacrament.[7]

The pulpits to the East, standing between the windows, were reserved for the Melchizedek Priesthood. Accordingly, each pulpit had initials identifying the priesthood office of the occupant. The top most pulpits read P.H.P., which stood for President of the High Priesthood. The next level down had P.S.Q for President of the Seventy Quorums. Below that, the labels were P.H.Q. which stood for President of the High priests Quorum, and the folding table had the inscription P.E.Q. standing for President of the Elders Quorum.[7]

Above the Eastern pulpits, written in gilded letters, along the arch of the ceiling, were the words,"The Lord Has Seen Our Sacrifice - Come After Us."[7]

The pulpits to the West end were reserved for the Aaronic Priesthood. Each pulpit similarly had initials identifying the priesthood officers who occupied that stand. The highest three pulpits bore the initials P.A.P., which stood for President of the Aaronic Priesthood. The next lower pulpits had P.P.Q., for President of the Priests Quorum). Again, the next had P.T.Q. for President of the Teachers Quorum and on the table at the bottom was written P.D.Q. for President of the Deacons Quorum.[7]

Pews

Similar to the Kirtland Temple, the hall was fitted with enclosed pews with two aisles running down its length. There were also pews for a band and choir. The room could accommodate up to 3,500 people. Because there were pulpits on both ends of the room, the pews had movable backs which could be swung to face either direction, depending on who was presiding - the Melchizedek Priesthood or the Aaronic Priesthood.[7]

First floor mezzanine

Access to the first floor mezzanine was directly from landings of the two staircases in the west end of the building. A foyer, corresponding in size to the vestibule below, connected the two stairway landings.

Evidence suggests that this mezzanine had fourteen small rooms, seven along each side of the North and South wall. Each room had a small circular window supplying light. These rooms may never have been completed, except perhaps some kind of partition dividing them.[7]

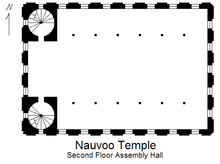

Second floor assembly hall

The second floor hall was similar in construction to the Great Hall, except that it included the foyer area where the vestibule would be. This made the room about seventeen feet longer. A 41-foot-long (12 m) stone arch ran north and south between the circular stairwells supporting the massive timbers for the tower above. It had seven large windows along the north and south wide, with four windows along the east wall.[7]

The floor would have a similar configuration as the Great Hall with a set of double pulpits and pews, but the room was never completed. Doors were never hung, the plastering was unfinished, and the floorboards were only rough timber, not the tongue and grove finished hardwoods of the other floors. The room, when used for an occasional meeting, was furnished with wooden benches.[7]

Second floor mezzanine rooms

The second mezzanine was similar to the first floor mezzanine. It was accessed via the two staircases at the West end of the building. There was no foyer connecting the two stairwells.[7]

The second floor mezzanine is also presumed to have been divided into fourteen small rooms, seven rooms along each side of the North and South walls of the building, between the arched ceiling of the second floor. Circular windows in the entablature of the building allowed for illumination. Just as with the second floor assembly room, there is no evidence that these rooms were ever completed, except perhaps for the partitions dividing each room. There was a staircase in the second room from the Southeast corner leading to a room above, providing another access method to the attic.[7]

Attic

At the top of the two stairways, opening to a foyer, was the attic floor. The attic was not built of limestone but of wood. It was composed of two sections. The West end of the temple was a flat roofed section that supported the tower. The rest of the attic was a pitched-roof section running the length of the temple.[7]

The flat-room section was further divided into two sections, the foyer on the west side, and a suite of rooms to the east. When the attic was used for ordinance work, they were used as a pantry, wardrobe and storage rooms. The area was illuminated by six windows along the foyer's west wall. Outside windows also provided light along the north and south sides. The roof had four octagonal skylight windows to provide light to the interior rooms, in addition to a twenty-foot arched window.[7]

The incline of the roof prevented a six-foot-tall man from standing erect along the outside wall. The second room from the south-east corner had a stairway leading to a room in the mezzanine below.[7]

Tower rooms

Rising from the plateau of the attic is an octagonal tower. The tower was divided into three sections, each accessible by a series of stairways leading from the attic to an observation deck at the top. The lowest section was the belfry. The bell was rung for various occasions. Between the observation deck and the belfry was a section containing the four clockwork mechanisms.[7]

See also

- Comparison of temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Joseph Toronto

- List of temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- List of temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by geographic region

- Temple architecture (LDS Church)

Notes

- ↑ Nauvoo Temple on ldschurchtemples.com

- ↑ Manuscript History of the Church, LDS Church Archives, book A-1, p. 37; reproduced in Dean C. Jessee (comp.) (1989). The Papers of Joseph Smith: Autobiographical and Historical Writings (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book) 1:302–03.

- ↑ H. Michael Marquardt and Wesley P. Walters (1994). Inventing Mormonism: Tradition and the Historical Record (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books) p. 160.

- 1 2 Brown, Lisle G. (February 2000). "Chronology of the Construction, Destruction, and Reconstruction of the Nauvoo Temple". Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ↑ Harrington, Virginia S.; Harrington, J.C. (1971), Rediscovery of the Nauvoo Temple: Report on the Archaeological Excavations, Salt Lake City: Nauvoo Restoration, p. 5, OCLC 247391

- ↑ Horner, Henry (1939), Illinois, A Descriptive and Historical Guide, Chicago: Federal Writer's Project of the Work Projects Administration for the State of Illinois, p. 352

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Nauvoo Temple Page

References

- Brown, Lisle G. (2002). ""A Perfect Estopel": Selling the Nauvoo Temple". Mormon Historical Studies. 3 (2): 61–85.

- Brown, Lisle G. (1979). "The Sacred Departments for Temple Work in Nauvoo: The Assembly Room and the Council Chamber". BYU Studies. 19 (3): 361–374.

- Brown, Lisle G. (2002). "Nauvoo's Temple Square". BYU Studies. 41 (4): 1–45.

- Colvin, Don (2002). The Nauvoo Temple: A Story of Faith. American Fork, Utah: Covenant Communications.

- Crocket, David R. (1999). "The Nauvoo Temple, A Monument of the Saints" (PDF). Nauvoo Journal. 11 (1): 5–30.

- McBride, Mathew S. (2007). A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple. Salt Lake City, Utah: Greg Kofford Books. ISBN 1-58958-016-8.

- Nauvoo: History in the Making. (2002) CD-ROM. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

External links

-

Media related to Nauvoo Temple at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nauvoo Temple at Wikimedia Commons - The Nauvoo Temple: the House of the Lord - A History of the Nauvoo Temple