Nine Stones, Winterbourne Abbas

The circle in 2004 | |

Shown within Dorset | |

| Location | Winterbourne Abbas |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°42′41″N 2°33′11″W / 50.711469°N 2.553019°W |

| Type | Stone circle |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic / Bronze Age |

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | English Heritage |

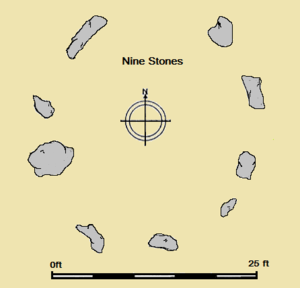

The Nine Stones, also known as the Devil's Nine Stones, the Nine Ladies, or Lady Williams and her Dog, is a stone circle located near to the village of Winterbourne Abbas in the south-western English county of Dorset. Archaeologists believe that it was likely erected during the Bronze Age. The Nine Stones is part of a tradition of stone circle construction that spread throughout much of Britain, Ireland, and Brittany during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, over a period between 3,300 and 900 BCE. The purpose of such monuments is unknown, although archaeologists speculate that they were likely religious sites, with the stones perhaps having supernatural associations for those who built the circles.

A number of these circles were built in the area around modern Dorset, typically being constructed from sarsen stone and being smaller than those found elsewhere in Britain. The Nine Stones circle has a diameter of 9.1 metres by 7.8 metres and consists of nine sarsen megaliths which are irregularly spaced. Two of the stones, both located on the north-western side of the monument, are considerably larger than the others. This architectural feature has parallels with various stone circles in south-western Scotland, and was potentially a deliberate feature by the circle's builders, to whom it may have had symbolic meaning.

Antiquarians like John Aubrey and William Stukeley first took an interest in the site during the 18th century. It later received archaeological attention, although has not been excavated. Local folklore has grown up around the circle, associating it with the Devil and with petrified children. The Nine Stones are regarded as a sacred site by local Druids, who perform religious ceremonies there. The circle is adjacent to the A35 road and encircled on its three other sides by trees. The site is owned by English Heritage and is open without charge to visitors.

Location

The Nine Stones circle is positioned at the national grid reference 36100904.[1] It is located on the southern side of the A35 road,[2] on the western edge of the village of Winterbourne Abbas.[3] Enclosed within iron railings, it is surrounded on three sides by trees and on the fourth by the A35.[4] The roots of a beech tree have engulfed two of the megaliths in the circle.[5] The archaeologist Aubrey Burl noted that while "this petite ring should be a delight to see", it was instead a "frustration" as a result of its restricted location.[2] He noted that it was difficult to take clear photographs of the site because of the surrounding trees.[2]

Context

While the transition from the Early Neolithic to the Late Neolithic—which took place with the transition from the fourth to the third millennium BCE—witnessed much economic and technological continuity, it also saw a considerable change in the style of monuments erected, particularly in southern and eastern England.[6] By 3000 BCE, the long barrows, causewayed enclosures, and cursuses which had predominated in the Early Neolithic had ceased being built, and were instead replaced by circular monuments of various kinds.[6] These include earthen henges, timber circles, and stone circles.[7] These stone rings are found in most areas of Britain where stone is available, with the exception of the island's south-eastern corner.[8] Stone circles are instead most densely concentrated in south-western Britain and on the north-eastern horn of Scotland, near Aberdeen.[8]

These stone circles typically show very little evidence of human visitation during the period immediately following their creation.[9] This suggests that they were not sites used for rituals that left archaeologically visible evidence, and may have been deliberately created to serve as "silent and empty monuments".[10] The archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson suggested that in Neolithic Britain, stone was associated with the dead and wood with the living.[11] Other archaeologists have suggested that the stone might not represent ancestors, but rather other supernatural entities, such as deities.[10]

The area of modern Dorset has only a "thin scatter" of stone circles,[12] with nine possible examples known within its boundaries.[13] The archaeologist John Gale described these as "a small but significant group" of such monuments,[13] and all are located within five miles of the sea.[14] All but one—Rempstone Stone Circle on the Isle of Purbeck—are located on the chalk hills west of Dorchester.[15] The Dorset circles have a simplistic typology, being of comparatively small size, with none exceeding 28 metres in diameter.[16] All are oval in shape, although perhaps have been altered from their original form.[17] With the exception of the Rempstone circle, all consist of sarsen stone.[15] Much of this may have been obtained from the Valley of Stones, a location at the foot of Crow Hill near to Littlebredy, which is located within the vicinity of many of these circles.[18] With the exception of the circle at Litton Cheney, none display evidence of any outlying stones or earthworks around the stone circle.[19]

The archaeologists Stuart and Cecily Piggott believed that the circles of Dorset were probably of Bronze Age origin,[20] a view endorsed by Burl, who noted that their distribution did not match that of any known Neolithic sites.[21] It is possible that they were not all constructed around the same date,[22] and the Piggotts suggested that while they may well be Early Bronze Age in date, it is also possible that "their use and possibly their construction may last into the Middle and even into the Late Bronze Age".[20] Their nearest analogies are the circles found on Dartmoor and Exmoor to the west, and the Stanton Drew stone circles to the north.[23] It is also possible that the stone circles were linked to a number of earthen henges erected in Dorset around the same period.[20]

Description and design

The Nine Stones circle has been described as "probably the most well documented of all those surviving in the county".[3] It measures 29 feet 10 inches by 25 feet 11 inches (9.1 metres by 7.9 metres) in diameter, as measured from a north-to-south direction.[24] The stones are of sarsen or conglomerate.[24][25] A gap between two stones on the side of the circle adjacent to the road may suggest that there was once a tenth stone in the monument.[26] Given its dimensions, the circle could only accommodate a small number of individuals assembling within it.[27]

Seven of the nine surviving stones are under 3 feet (90 centimetres) tall, however the further two stones—both located on the north-west of the site—are considerably larger.[2] One is thin and pointed, reaching 7 feet (2.1 metres) high, while the other is broader, measuring 6 feet by 6 feet (1.8 metres square).[2] These two larger stones are located opposite the circle's two shortest stones.[2] The largest of the stones weighs approximately 8 tons (7.3 tonnes) and would have required the efforts of many people to move and erect it.[21]

This disparity between the sizes of the megaliths is unparalleled among the other surviving stone circles in the Dorset area.[28] This disparity may have been a deliberate choice by the circle's builders, perhaps reflecting sexual symbolism.[2] There are a number of similar circles in south-western Scotland, for example the Loupin' Stones, Ninestane Rigg, and Burgh Hill, all of which share the architectural feature of having two taller stones on their perimeters.[29] Potentially supporting this link between Dorset and south-western Scotland is the fact that the Grey Mare and her Colts—a chambered long barrow located two and a half miles south-west of the Nine Stones—displays architectural similarities with the Clyde-Solway tradition of chambered long barrows.[30]

Landscape context and related monuments

The circle is located at the bottom of a narrow valley.[31] Though this is unusual for a monument of this type,[31] the Dorset Rempstone stone circle was also erected within a valley.[32]

The antiquarian John Aubrey recorded a further stone circle, located about half a mile (approximately 1 kilometre) to the west of the Nine Stones, which was of similar dimensions to it.[32] It was later destroyed, although as of the 1930s three stones were recorded as remaining at the site.[32] Gale later suggested that this site may not have even been a stone circle at all, but might instead have been the remains of an Early Neolithic chambered tomb. He noted, however, that "as nothing remains it is at the moment impossible to resolve".[33]

There is also a fallen standing stone known as the Broad Stone which measures 6.6 feet (2 metres) in length and which lies beside the road about 0.9 miles (1.5 kilometres) to the west of the Nine Stones.[33][34] As it was recorded in the 19th century it measured 10 feet (3 metres) in length, 6 and a half (2 metres) feet in breadth, and 2 feet (0.6 metres) in thickness.[33] The monument was protected from passing cars by several bollards which were later removed by the highways authority, prompting statements of concern that the stone was unprotected in 2008.[35]

Later history

Antiquarian and archaeological research

The circle was recorded by Aubrey in the 17th century, and then by William Stukeley in the 18th century.[25] Aubrey recorded the presence of nine megaliths at the site, as did Stukeley's 1723 drawing of it.[28] In the nineteenth century the site was visited by the antiquarian Charles Warne, who wrote about it in his 1872 book Ancient Dorset. He claimed that he could discern the existence of a tenth stone, although on visiting the site in 1936, the Piggotts noted that they could find no evidence of this.[37] Gale later stated that this claim "has never been substantiated".[3] Warne had consulted Aubrey's manuscript, but confused Aubrey's illustration of the Devil's Quoits at Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire for a monument that he believed had once been located near to the Nine Stones.[32]

In 1888, the local council decreed that—along with the Grey Mare and her Colts and the Tenant Hill stone circle—the site would be registered as an "ancient monument" under the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882.[38] The circle was included in the archaeologist O. G. S. Crawford's Map of Neolithic Wessex, printed by the Ordnance Survey in 1932.[15] As of 2003, the site had not been excavated.[39]

Folklore

In 1908, the stone circle was known as the "Nine Ladies" and the "Devil's Nine Stones",[40] and in 1941 they were associated with both the Devil and with human sacrifice in local folklore.[40] As of 1968, the stone circle was still known as the "Devil's Nine Stones".[41] In 1966, a man from Winterborne St Martin claimed that the stones were the Devil, his wife, and his children.[42] There are many ancient sites across Britain with names which associate them with the Devil.[43] Examining such place-names, the folklorist Jeremy Harte argued that they did not develop during the Christianisation of England in the early Middle Ages, but rather they were applied to such sites in later centuries, often supplanting the name of an earlier folkloric or legendary figure.[44]

In 1965 a woman from the Isle of Portland stated that her own father had always raised his cap when passing the circle.[45] At the same time local folklore was recorded as holding that the stones in the ring could not be counted.[45] This "countless stones" motif is not unique to this particular site, and can be found at various other megalithic monuments in Britain. The earliest textual evidence for it is found in an early sixteenth-century document, where it applies to the stone circle of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, although in an early seventeenth-century document it was being applied to The Hurlers, a set of three stone circles in Cornwall.[46] Later records reveal that it had gained widespread distribution in England, as well as a single occurrence each in Wales and Ireland.[47] The folklorist S. P. Menefee suggested that it could be attributed to an animistic understanding that these megaliths had lives of their own.[48]

The archaeologist Leslie Grinsell reported that in the mid-1970s, he learned of a folk tale that the stones had once been children who were turned to stones as punishment for playing Five-Stones on a Sunday.[49] This folk motif of humans turned to stone for revelling on a Sunday had been attached to a range of prehistoric monuments across south-western Britain by the early eighteenth century, although had had been first recorded in Cornwall in 1602.[50] It is likely connected to Sabbatarianism, and may have been spread by Protestant preachers.[51]

In 1984, Harte talked to various individuals who lived in the local area, finding that the monument was also known as "Lady Williams and her Dog" or "Lady Williams and her Little Dog Fido", a reference to a family who lived at Bridehead.[52] He also related a story that on 23 January 1985, a breakdown van was towing a car passed the Nine Stones when, at 9.15pm, its engine cut out and the lights on both vehicles failed. Press coverage speculated that the event was linked to both a ley line passing through the site and to unidentified flying objects that have been reported above the nearby Eggardon Hill.[52]

Recent developments

The site is in the care of English Heritage,[25] and can be visited at any time.[1] The site is considered a place of religious importance to a modern Druidic group, the Dolmen Grove Druids.[53] They have described having to confront individuals shouting abuse at them while they have performed their rituals at the stone circle.[54]

In October 2007, the sides of the stones facing the road were daubed in white paint with the slogans "Read family court hell" and "F4J". "F4J" was also painted on to the side of Dorset's Hardy Monument. The activist group Fathers4Justice—whose acronym is "F4J"—denied any responsibility, condemned the action, and suggested that the slogans had been painted on by unknown individuals in an attempt to discredit the group.[55] Concern about the vandalism was expressed by the National Trust, the local landowner, and the Dolmen Grove Druids.[53]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 Gale 2003, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Burl 2005, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Gale 2003, p. 74.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 309; Burl 2005, p. 68.

- ↑ Castleden 2015, p. 97.

- 1 2 Hutton 2013, p. 81.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 91–94.

- 1 2 Hutton 2013, p. 94.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 97.

- 1 2 Hutton 2013, p. 98.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 307.

- 1 2 Gale 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 308.

- 1 2 3 Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 138.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 139; Burl 2000, p. 308; Gale 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 308; Gale 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 308; Gale 2003, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 142.

- 1 2 Burl 2000, p. 310.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 141.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 140.

- 1 2 Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 Historic England. "The Nine Stones (453624)". PastScape. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 146; Castleden 2015, p. 97.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 309.

- 1 2 3 Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 146.

- ↑ Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 119; Burl 2000, p. 309; Gale 2003, p. 74; Burl 2005, p. 68.

- ↑ Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 119; Burl 2000, p. 309; Burl 2005, p. 68.

- 1 2 Gale 2003, p. 74; Burl 2005, p. 309; Castleden 2015, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Gale 2003, p. 75.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Broad Stone (451206)". PastScape. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ Hendy 2008.

- ↑ Burl 2005, p. 67.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Anonymous 1888, p. 385; Anonymous 1888b, p. 51.

- ↑ Gale 2003, pp. 72, 169.

- 1 2 Harte 1986, p. 67.

- ↑ Wightman 1968, p. 86; Grinsell 1976, p. 109; Harte 1986, p. 67.

- ↑ Waring 1977, p. 32; Grinsell 1976, p. 109; Harte 1986, p. 67.

- ↑ Harte 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Harte 2009, pp. 26–32.

- 1 2 Waring 1977, p. 32; Harte 1986, p. 67.

- ↑ Menefee 1975, p. 146.

- ↑ Menefee 1975, p. 147.

- ↑ Menefee 1975, p. 148.

- ↑ Grinsell 1976, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Hutton 2009, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Grinsell 1976, p. 56; Hutton 2009, p. 13.

- 1 2 Harte 1986, p. 68.

- 1 2 Jenkins 2007.

- ↑ Anonymous 2007.

- ↑ Jenkins 2007; BBC News 2007.

Bibliography

- Anonymous (2 June 1888). "Notes on Art and Archaeology". The Academy (839). p. 385.

- ⸻ (1888b). "Quarterly Summary of Archaeological Discoveries in the British Isles". The Archaeological Review. 2 (1). pp. 50–54. JSTOR 24708701.

- ⸻ (17 March 2007). "Pagans suffer ritual abuse". Dorset Echo. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- BBC News (24 October 2007). "Vandals target two historic sites". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Burl, Aubrey (2000). The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08347-7.

- ⸻ (2005). A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11406-5.

- Castleden, Rodney (2015) [1992]. Neolithic Britain: New Stone Age Sites of England, Scotland and Wales. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05845-2.

- Gale, John (2003). Prehistoric Dorset. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2906-9.

- Grinsell, Leslie V. (1976). Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7241-6.

- Harte, Jeremy (1986). Cuckoo Pounds and Singing Barrows: The Folklore of Ancient Sites in Dorset. Dorchester: Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society. ISBN 0-900341-23-8.

- ⸻ (2009). "The Devil's Chapels: Fiends, Fear and Folklore at Prehistoric Sites". In Joanne Parker (ed.). Written on Stone: The Cultural Reception of British Prehistoric Monuments. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 23–35. ISBN 978-1-4438-1338-9.

- Hendy, Arron (13 December 2008). "Fears for future of ancient stone". Dorset Echo. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Hutton, Ronald (2009). "Megaliths and Memory". In Joanne Parker (ed.). Written on Stone: The Cultural Reception of British Prehistoric Monuments. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 10–22. ISBN 978-1-4438-1338-9.

- ⸻ (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19771-6.

- Jenkins, Gill (25 October 2007). "Fathers group denies attack on monuments". Dorset Echo. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Menefee, S. P. (1975). "The 'Countless Stones': A Final Reckoning". Folklore. The Folklore Society. 86 (3-4): 146–166. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1975.9716017. JSTOR 1260230.

- Piggott, Stuart; Piggott, C. M. (1939). "Stone and Earth Circles in Dorset". Antiquity. 13 (50). pp. 138–158. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00027861.

- Thom, Alexander; Thom, Archibald Stevenson; Burl, Aubrey (1980). Megalithic Rings: Plans and Data for 229 Monuments in Britain. BAR British Series 81. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 0-86054-094-4.

- Waring, Edward (1977). Ghosts and Legends of the Dorset Countryside. Tisbury: Compton Press. ISBN 978-0-900193-51-4.

- Wightman, R. (1968). Portrait of Dorset (second ed.). London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-0844-6.

External links

![]() Media related to Nine Stones (Winterbourne Abbas) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nine Stones (Winterbourne Abbas) at Wikimedia Commons

- The Nine Stones, English Heritage