Ninhydrin

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2,2-Dihydroxy-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione | |

| Other names

2,2-Dihydroxyindane-1,3-dione 1,2,3-Indantrione hydrate | |

| Identifiers | |

| 485-47-2 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1221925 |

| ChemSpider | 9819 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.926 |

| PubChem | 10236 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H6O4 | |

| Molar mass | 178.14 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Density | 0.862 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 250 °C (482 °F; 523 K) (decomposes) |

| 20 g L−1[1] | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| R-phrases | R22, R36, R37, R38 |

| S-phrases | S26, S28, S36 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

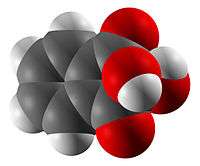

Ninhydrin (2,2-dihydroxyindane-1,3-dione) is a chemical used to detect ammonia or primary and secondary amines. When reacting with these free amines, a deep blue or purple color known as Ruhemann's purple is produced. Ninhydrin is most commonly used to detect fingerprints, as the terminal amines of lysine residues in peptides and proteins sloughed off in fingerprints react with ninhydrin.[2] It is a white solid which is soluble in ethanol and acetone at room temperature.[1] Ninhydrin can be considered as the hydrate of indane-1,2,3-trione.

History

Ninhydrin was discovered in 1910 by the German-English chemist Siegfried Ruhemann (1859–1943).[3][4] In the same year, Ruhemann observed ninhydrin's reaction with amino acids.[5] In 1954, Swedish investigators Oden and von Hofsten proposed that ninhydrin could be used to develop latent fingerprints.[6][7]

Uses

Ninhydrin can also be used to monitor deprotection in solid phase peptide synthesis (Kaiser Test).[8] The chain is linked via its C-terminus to the solid support, with the N-terminus extending off it. When that nitrogen is deprotected, a ninhydrin test yields blue. Amino-acid residues are attached with their N-terminus protected, so if the next residue has been successfully coupled onto the chain, the test gives a colorless or yellow result.

Ninhydrin is also used in amino acid analysis of proteins. Most of the amino acids, except proline, are hydrolyzed and react with ninhydrin. Also, certain amino acid chains are degraded. Therefore, separate analysis is required for identifying such amino acids that either react differently or do not react at all with ninhydrin. The rest of the amino acids are then quantified colorimetrically after separation by chromatography.

A solution suspected of containing the ammonium ion can be tested by ninhydrin by dotting it onto a solid support (such as silica gel); treatment with ninhydrin should result in a dramatic purple color if the solution contains this species. In the analysis of a chemical reaction by thin layer chromatography (TLC), the reagent can also be used (usually 0.2% solution in either n-butanol or in ethanol). It will detect, on the TLC plate, virtually all amines, carbamates and also, after vigorous heating, amides.

When ninhydrin reacts with amino acids, the reaction also releases CO2. The carbon in this CO2 originates from the carboxyl carbon of the amino acid. This reaction has been used to release the carboxyl carbons of bone collagen from ancient bones[9] for stable isotope analysis in order to help reconstruct the palaeodiet of cave bears.[10] Release of the carboxyl carbon (via ninhydrin) from amino acids recovered from soil that has been treated with a labeled substrate demonstrates assimilation of that substrate into microbial protein.[11] This approach was successfully used to reveal that some ammonium oxidizing bacteria, also called nitrifying bacteria use urea as a carbon source in soil.[12]

A ninhydrin solution is commonly used by forensic investigators in the analysis of latent fingerprints on porous surfaces such as paper. Amino acid containing fingermarks, formed by minute sweat secretions which gather on the finger's unique ridges, are treated with the ninhydrin solution which turns the amino acid finger ridge patterns purple and therefore visible.[13]

Reactivity

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Indane-1,2,3-trione | |

| Other names

Indanetrione | |

| Identifiers | |

| 938-24-9 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 63492 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.926 |

| PubChem | 70309 |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H4O3 | |

| Molar mass | 160.13 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Density | 1.482 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 338.4 °C (641.1 °F; 611.5 K) |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

The carbon atom of a carbonyl bears a partial positive charge enhanced by neighboring electron withdrawing groups like carbonyl itself. So the central carbon of a 1,2,3-tricarbonyl compound is much more electrophilic than one in a simple ketone. Thus indane-1,2,3-trione reacts readily with nucleophiles, including water. Whereas for most carbonyl compounds, a carbonyl form is more stable than a product of water addition (hydrate), ninhydrin forms a stable hydrate of the central carbon because of the destabilizing effect of the adjacent carbonyl groups.

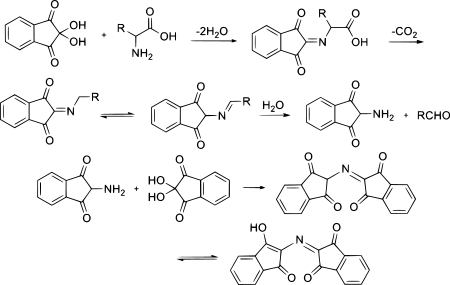

Note that to generate the ninhydrin chromophore (2-(1,3-dioxoindan-2-yl)iminoindane-1,3-dione), the amine is condensed with a molecule of ninhydrin to give a Schiff base. Thus only ammonia and primary amines can proceed past this step. At this step, there must be an alpha hydrogen present to form the Schiff base. Therefore, amines bound to tertiary carbons do not react further and thus are not detected. The reaction of ninhydrin with secondary amines gives an iminium salt, which is also coloured, and this is generally yellow–orange in color.

See also

References

- 1 2 Chemicals and reagents, 2008–2010, Merck

- ↑ Fingerprinting Analysis. bergen.org

- ↑ Ruhemann, Siegfried (1910). "Cyclic Di- and Tri-ketones". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 97: 1438–1449. doi:10.1039/ct9109701438.

- ↑ West, Robert (1965). "Siegfried Ruhemann and the discovery of ninhydrin". Journal of Chemical Education. 42 (7): 386–388. doi:10.1021/ed042p386.

- ↑ Ruhemann, S. (1910). "Triketohydrindene Hydrate". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 97: 2025–2031. doi:10.1039/ct9109702025.

- ↑ Odén, Svante & von Hofsten, Bengt (1954). "Detection of fingerprints by the ninhydrin reaction". Nature. 173 (4401): 449–450. doi:10.1038/173449a0. PMID 13144778.

- ↑ Oden, Svante. "Process of developing fingerprints," U.S. Patent no. 2,715,571 (filed: September 27, 1954 ; issued: August 16, 1955).

- ↑ Kaiser, E.; Colescott, R.L.; Bossinger, C.D.; Cook, P.I. (1970). "Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides". Analytical Biochemistry. 34 (2): 595. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6.

- ↑ Keeling, C. I.; Nelson, D. E. & Slessor, K. N. (1999). "Stable carbon isotope measurements of the carboxyl carbons in bone collagen" (PDF). Archaeometry. 41: 151. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1999.tb00857.x.

- ↑ Keeling, C. I.; Nelson, D. E. (2001). "Changes in the intramolecular stable carbon isotope ratios with age of the European cave bear (Ursus spelaeus)". Oecologia. 127 (4): 495. doi:10.1007/S004420000611. JSTOR 4222957.

- ↑ Marsh, K. L., Mulvaney, R. L. and Sims, G. K. (2003). "A technique to recover tracer as carboxyl-carbon and α-nitrogen from amino acids in soil hydrolysates". J. AOAC. 86 (6): 1106–1111. PMID 14979690.

- ↑ Marsh, K. L., Sims, G. K. and Mulvaney, R. L. (2005). "Availability of urea to autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria as related to the fate of 14C- and 15N-labeled urea added to soil". Biol. Fert. Soil. 42 (2): 137–145. doi:10.1007/s00374-005-0004-2.

- ↑ Menzel, E.R. (1986) Manual of fingerprint development techniques. Home Office, Scientific Research and Development Branch, London. ISBN 0862522307