Noin-Ula burial site

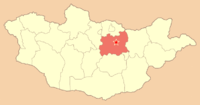

The Noin-Ula burial site (Mongolian: Ноён уулын булш, Noyon uulyn bulsh) consist of more than 200 large burial mounds, approximately square in plan, some 2 m in height, covering timber burial chambers. They are located by the Selenga River in the hills of northern Mongolia north of Ulan Bator in Batsumber sum of Tov Province. They were excavated in 1924–1925 by Pyotr Kozlov, who found them to be the tombs of the aristocracy of the Xiongnu;[1] one is an exceptionally rich burial of a historically known ruler of the Xiongnu, Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy, who died in 13 CE. Most of the objects from Noin-Ula are now in the Hermitage Museum, while some artifacts unearthed later by Mongolian archaeologists are on display in the National Museum of Mongolian History, Ulan Bator. Two kurgans contained lacquer cups, inscribed with Chinese characters believed to be the names of Chinese craftsmen, and dated September 5 year of Tsian-ping era, i.e. 2nd year BCE.

Noin-Ula kurgans

As with some finds of the Pazyryk culture, the Noin Ula graves had been flooded and subsequently frozen, thus preserving the organic material to a remarkable degree. The tombs were opened in antiquity and the bodies were removed. This corroborates the Han chronicles which state the leaders of one of the nomad tribes, oppressed by the Xiongnu at the height of their empire, took an unprecedented step 100 years after the decline of the Xiongnu. Wishing to unite their subjects, and driven by a desire for revenge, the new nomadic leaders desecrated the Chanuys' royal tombs. All the burials were unsealed, and the remains of the Chanuys were removed, together with some of their clothing, weaponry and symbols of authority. However, the robbers left Xiongnu weaponry, home utensils, and art objects, and Chinese artifacts of bronze, nephrite, lacquered wood and textiles. Many artifacts show origins along the Great Silk Road; some imported objects and fragments of fabrics are recognized as Greek. The fabric, color, weaving methods and embroidery of the cloth were similar to the fabric produced in the Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast for the Scythians.

Some tombs include horse burials and one tomb had especially lavish furnishings. The coffin was apparently made in China, and the interred person had many of his possessions buried with him. His horse trappings were elaborately decorated and his leather-covered saddle was threaded with black and red wool clipped to resemble velvet. Magnificent textiles included a woven wool rug lined with thin leather with purple, brown, and white felt appliqué work, and textiles of Greco-Bactrian, Parthian and Anatolian origin.

Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy

Kurgan No 6 was the tomb of Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy (Uchilonoti, Ulunoti, 烏珠留若提 Wu-Zhou-Liu-Ju-Di, reigned 8 BCE–13 CE), who is mentioned in the Chinese annals. He is famous for freeing his people from the Chinese protectorate that lasted 56 years, from 47 BCE to 9 CE. Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy was buried in 13 CE, a date established from the inscription on a cup given to him by the Chinese Emperor during a reception in the Shanlin park near Chang'an in 1 BCE.

During the life of Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy, the Chinese dominated the steppe politically. For a generous reward by the Chinese,[2] he changed his personal name Nanchjiyasy to Chji. On ascending to the throne, he confirmed the standing agreement between the Han Chinese and the Xiongnu: "Henceforth the Han and Hun will be one House, from generation to generation they will not deceive each other, nor attack each other. If a larceny happens, they will mutually inform and execute and compensate, in the event of raids by enemies they will help each other with troops. He of them who is first to breach the agreement, he will be penalized by the Sky, and his posterity from generation to generation would suffer under I this oath".

Despite this agreement, during Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy's reign relations with China went from cordial to antagonistic when a usurper Wang Mang came to power, which ended the Western Han Dynasty, and establishing the short-lived Xin Dynasty. Assembling a 300,000-strong army, Wang Mang began military actions, but his attempts ended in futility. Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy died in AD 13, before the end of the war. His successor was Uley-Jodi-Chanuy of the Süybu clan.

The most dramatic objects of Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy's funeral inventory are the textiles, of local, Chinese and Bactrian origin. The art objects show that Xiongnu craftsmen used the Scythian "animal" style.

A surviving portrait shows a low nose bridge, eyes with epicanthic fold, long wavy hair, divided in the middle, and a braid tied visibly and falling from the tip of the head over the right ear. Such braids were found in other kurgan tombs in the Noin Ula cemetery, they were braided from horsehair, and kept in special cases. The braid was a part of a formal hairstyle, and the braid resembles the death-masks of the Tashtyk. This appearance of the masks demonstrate that in the 1st century AD a far-eastern appearance was perceived by the Huns as more attractive than one of western type, resembling modern Telengits who consider large eyes and high nose to be ugly. From these observations, L.N. Gumilev concluded that among the Huns of the 1st century BC, a far-eastern ideal of beauty overcame the traditional western model, which continued in the art of the Scythian "animal" style.

Culture

The cultural affinity of the Xiongnu was with the peoples of southern Siberia and Central Asia; with the Chinese they exchanged arrows rather than culture: the Xiongnu shot with hand bows, while Chinese employed crossbows, although the Chinese had developed the crossbow from the traditional hand bows. Lev Gumilev elaborates the roots of the Chinese cultural influence found in the Noin-Ula cemetery. The Chinese culture was spread not only by material objects, but also by population admixture. There were populations of Xiongnu that have live under the Han rule as military allies. The Chinese migrated continuously to the steppes, the first big wave arriving in the 3rd century BC during the Tsin dynasty (Pin. Qin), when captured Chinese became subjects of the Chanuys, a process repeated during the following centuries. The numerous Han people who deserted and entered Chanuy service (for example, Vey Lüy, Li Lin) also taught the Xiongnu the subtlety of diplomacy and martial arts. Populations of the Xiongnu people also lived under Han rule, mostly serving as military allies under Han command. The capture of populations of Xiongnu by the Han forces in a series of Han versus Hun wars also contributed to additional ethnic integration of the north-central Asian neighbors.

Many immigrants lived in the Xiongnu pasturelands, but at first they did not mix with the Xiongnu. To be a Xiongnu, one had to be a member of a clan, born of Xiongnu parents. The newcomers were well off, but were outsiders, and could marry only among themselves, not the Xiongnu. Only later did they intermix, increase in numbers, even created a state that existed from 318 to 350 AD.

The Xiongnu culture can be differentiated into local, Scytho-Sarmatian, and Chinese. Most everyday objects were produced locally, showing the stability of the nomadic culture; Chinese masters made small handmade objects and ornaments, while objects with ideological connotations originated from the Scythian, Sarmatian and Dinlin S. Siberian cultures.[3]

Despite the aforementioned excavated Noin-Ula portrait indicating Mongoloid lineage of the Xiongnu, Euro-centric observers of Xiongnu culture and history try to place the Xiongnu people in a non-Mongoloid or non-Asian ancestry or descendancy. Among the most important artifacts from Noin-Ula are embroidered portrait images. These shed light on the ethnicity of the Xiongnu, albeit controversially. It has been claimed that the portraits depict Greco-Bactrians, or are Greek depictions of Scythian soldiers from the Black Sea. Such suggestions are far-fetched. There are several historical sources confirming the appearance of the Xiongnu. In 350 AD, for example, power in the South Xiongnu state of Chjao (Pin. Zhao) was seized by a usurper, a Chinese named Shi Min, who ordered all the Xiongnu in the state exterminated; in the slaughter "many Chinese with prominent noses" died, suggesting the Xiongnu had "prominent noses" compared to those of the Chinese. In the famous Chinese bas-relief "Fight on the bridge" the mounted Xiongnu are shown with big noses. A skull analysis of Xiongnu burials made by G.F. Debets found a distinct Paleo-Siberian type of Asian facial appearance with "not a flat, but with not strongly protruding nose", somewhat similar to some North American Indians. This type is represented on the embroidery from Noin-Ula. What to the rest of the Chinese looked like a high nose, to the Europeans looked like a flat nose.

The portraits are not made in the Chinese manner, and are the handiwork of a Central Asian or Scythian artist, or perhaps of a Bactrian or Parthian master in the capital of the Chanüys (who had active diplomatic relations with these Central Asian states).

The hairstyle on one portrait shows long hair bound with a wide ribbon. This is identical with the coiffure of the Türkic Ashina clan, who were originally from the Hesi province. The Ashina belonged to the last Xiongnu princedom destroyed by Xianbei-Toba by AD 439. From Gansu, the Ashina retreated to the Altai, taking with them a number of distinctive ethnographic traits.

Literacy

Chinese sources indicate that the Xiongnu did not have an ideographic form of writing like Chinese, but in the 2nd century BC, a renegade Chinese dignitary Yue "taught the Shanyu to write official letters to the Chinese court on a wooden tablet 31 cm long, and to use a seal and large-sized folder." The same sources tell that when the Xiongnu noted down something or transmitted a message, they made cuts on a piece of wood ('ke-mu'), and they also mention a "Hu script". At Noin-Ula and other Xiongnu burial sites in Mongolia and the region north of Lake Baikal, among the objects were discovered over 20 carved characters. Most of these characters are either identical or very similar to letters of the Turkic Orkhon-Yenisey script of the Early Middle Ages found on the Eurasian steppes. From this, some specialists conclude that the Xiongnu used a script similar to the ancient Eurasian runiform, and that this alphabet was a basis for later Turkic writing.[4]

Anthropology

The Noin-Ula burials were intensively studied, but because the cemetery was desecrated in antiquity and bodies removed, no craniological, odontological, or genetic studies could be conducted. One exception is the odontological study of preserved enamel caps of seven permanent teeth belonging to a young woman. The study describes highly diagnostic traits with a very rare combination found in certain ancient and modern populations of the Caspian–Aral region and in the northern Indus–Ganges interfluve. A Parthian woolen cloth in the grave indicates that the woman was of northwestern Indian origin associated with the Parthian culture. The finds suggest that at the beginning of the Common Era, peoples of Parthian origin were incorporated within Xiongnu society.[5] Parthians belonged to the tribal union called in ancient Greek Dahae, also known as Tokhars and in Chinese as Yuezhi.

-

Oldest known Türkic alphabet listings, Rjukoku and Toyok manuscripts. Toyok manuscript transliterates Türkic alphabet into Uygur alphabet. Per I.L.Kyzlasov, "Runic Scripts of Eurasian Steppes", Moscow, Eastern Literature, 1994.

See also

References

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Bichurin N.Ya., "Collection of information on peoples in Central Asia in ancient times", vol. 1, M.-L., 1950, p. 101

- ↑ Rudenko S.I. & Gumilev L.N., 'Archaeological Studies of P.K. Kozlov from standpoint of historical geography', Communications of the All-Union Geographical Society, No 3, 1966

- ↑ N. Ishjatms, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, Fig 6, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

- ↑ Chikisheva, T.A.; et al. (2009). "Dental remains From Kurgan 20 At Noin-ula, Mongolia". Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 37 (3): 145–151. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2009.11.016.

Additional Reading

- S. S. Minyaev. To the interpretation of some finds from Noyon uul //Anciemt Cultures of Eurasia. St-Petersburg, 2010: 182-186.

- Sergei Miniaev, Julia Elikhina。On the Chronology of the Noyon uul Barrows// The Silk Road 7 (2009): 21-35

- V. E. Kulikov, E. Iu. Mednikova, Iu. I. Elikhina, S. S. Miniaev. AN EXPERIMENT IN STUDYING THE FELT CARPET FROM NOYON UUL BY THE METHOD OF POLYPOLARIZATION// The Silk Road 8 (2010): 73-78.

- V. N. Kononov. Vosstanovlenie pervonachal’nykh krasok kovra iz Noin-Ula [Restoration of the

original colors of a carpet from Noyon uul]. Moscow-Leningrad, 1937.

- Kratkie otchety ekspeditsii po issledovaniiuSevernoi Mongolii v sviazi s Mongolo-Tibetskoi

ekspeditsii P. K. Kozlova [Brief reports of the expedition to study Northern Mongolia in conjunction with the Mongolia-Tibetan expedition of P. K. Kozlov]. Leningrad, 1925.

- S. S. Miniaev. “Bronzovye izdeliia Noin-Uly (po rezul’tatam spektral’nogo analiza) [Bronze

artefacts of Noyon uul (results of spectroscopic analysis)]. //Kratkie soobshcheniia Instituta arkheologii 167 (1981):

- A. A. Voskresenskii and V. N. Kononov. "Khimiko-tekhnologicheskii analiz kovra No. 14568" [Technical chemical analysis of carpet no. 14568]. In: Tekhnologicheskoe izuchenie tkanei kurgannykh pogrebenii Noin-Ula [Technical study of the fabrics from the burial barrows of Noyon uul]. Izvestiia GAIMK, XI/vyp. 7-9. Leningrad, 1932: 76–98.

- Trever C. "Excavations in Northern Mongolia (1924–1925)", Leningrad: J. Fedorov Printing House, 1932

- Rudenko S.I. "Hun Culture and Noin Ula kurgans", M-L, 1962 (In Russian)

- Rudenko S.I., Gumilev L.N., "Archaeological Studies of P.K.Kozlov from standpoint of historical geography", in News of All-Union Geographical Society No 3, 1966 (In Russian)

- Gumilev L.N., "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 12 Regained Freedom http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph12.htm

- N. Ishjatms, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

- http://xiongnu.atspace.com

- http://eurasica.xiongnu.ru

- Video: Xiongnu – the burial site of the Hun prince (Mongolia) Video-Documentation in 10 Episodes