Northern goshawk

| Northern goshawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Accipiter |

| Species: | A. gentilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Accipiter gentilis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

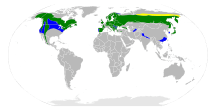

| Range of A. gentilis Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

The northern goshawk /ˈɡɒs.hɔːk/ (Old English: gōsheafoc, "goose-hawk"), Accipiter gentilis, is a medium-large raptor in the family Accipitridae, which also includes other diurnal raptors, such as eagles, buzzards and harriers. As a species in the Accipiter genus, the goshawk is often considered a true "hawk".

It is a widespread species that inhabits the temperate parts of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the only species in the Accipiter genus found in both Eurasia and North America. With the exception of Asia, it is the only species of "goshawk" in its range and it is thus often referred to, both officially and unofficially, as simply the "goshawk". It is mainly resident, but birds from colder regions migrate south for the winter. In North America, migratory goshawks are often seen migrating south along mountain ridge tops in September and October.

The northern goshawk appears on the flag of the Azores. The archipelago of the Azores, Portugal, takes its name from the Portuguese language word for goshawk, (açor), because the explorers who discovered the archipelago thought the birds of prey they saw there were goshawks; later it was found that these birds were kites or common buzzards (Buteo buteo rothschildi).

The goshawk features in the crest of the Drummond Clan.

Taxonomy

The first formal description of the northern goshawk was by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Falco gentilis.[3][4] The current genus Accipiter was introduced by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[5][6] The scientific name is Latin; Accipiter is "hawk", from accipere, "to grasp", and gentilis is "noble" or "gentle" because in the Middle Ages only the nobility were permitted to fly goshawks for falconry.[7]

Description

The northern goshawk is the largest member of the genus Accipiter.[8] It is a raptor with short, broad wings and a long tail, both adaptations to manoeuvring within its forest habitat. Across most of the species' range, it is blue-grey above and barred grey or white below, but Asian subspecies in particular range from nearly white overall to nearly black above. The juvenile is brown above and barred brown below. Juveniles and adults have a barred tail, with dark brown or black barring. Adults always have a white eye stripe. In North America, juveniles have pale-yellow eyes, and adults develop dark red eyes usually after their second year, although nutrition and genetics may affect eye color as well. In Europe and Asia, juveniles also have pale-yellow eyes while adults develop orange-colored eyes.

The northern goshawk, like all accipiters, exhibits sexual dimorphism, where females are significantly larger than males. Males, being the smaller sex by around 10 – 25%, are 46–57 cm (18–22 in) long and have a 89–105 cm (35–41 in) wingspan.[9][10] The female is much larger, 58–69 cm (23–27 in) long with a 108–127 cm (43–50 in) wingspan.[9][10] Males average around 780 g (1.72 lb), with a range of 500 to 1,200 g (1.1 to 2.6 lb).[9] The female can be more than twice as heavy, averaging 1,220 g (2.69 lb) with a range of 820 to 2,200 g (1.81 to 4.85 lb).[9] Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 28.6–39 cm (11.3–15.4 in), the tail is 20–28 cm (7.9–11.0 in), the culmen is 2–2.6 cm (0.79–1.02 in) and the tarsus is 6.8–9 cm (2.7–3.5 in).[9][11][12] In Eurasia, the species follows Bergmann's rule: specimens from the northern races generally are larger-bodied than goshawks near the southern reaches of the species range.[9] Going on wing chord length, A. g. apache, found in Mexico to Arizona and New Mexico, is the largest subspecies at an average of 36.8 cm (14.5 in) and is larger than more northern subspecies in that continent, thus running contrary to Bergmann's rule. A. g. fujiyamae of Japan is the smallest race, at 30.9 cm (12.2 in) in wing chord length.[9] In Europe, goshawks from Finland or of Finnish ancestry are prized as bigger than other goshawks.

The flight is a characteristic "flap flap, glide", but the bird is sometimes seen soaring in migration, and is capable of considerable, sustained, horizontal speed in pursuit of prey with speeds of 38 mph (61 km/h) reported.[13] Goshawks are sometimes confused with gyrfalcons, especially when observed in high speed pursuit, with their wingtips drawn backward in a falcon-like profile.

In Eurasia, the male is sometimes confused with a female sparrowhawk, but is larger, much bulkier and has relatively longer wings. In North America, juveniles are sometimes confused with the smaller Cooper's hawk; however, the juvenile goshawk displays a heavier, vertical streaking pattern on their chest and abdomen and sometimes appears to have a shorter tail due to its much larger and broader body. Although there appears to be a size overlap between small male goshawks and large female Cooper's hawks, morphometric measurements (wing and tail length) of both species demonstrate no such overlap, although weight overlap can occur due to variation in seasonal condition and food intake at time of weighing. In North America, the sharp-shinned hawk is markedly smaller.

Habitat

Northern goshawks can be found in both deciduous and coniferous forests. They seem to thrive only in areas with mature, old-growth woods and are typically found where human activity is relatively low. During nesting season, they favor tall trees with intermediate canopy coverage and small openings below for hunting. They can be found at almost any altitude, but recently are typically found at high elevations due to a paucity of extensive forests remaining in lowlands across much of its range. In winter months, the northernmost populations move down to warmer forests with lower elevations, continuing to avoid detection except while migrating. A majority of goshawks around the world remain sedentary throughout the year.[14][15]

Food and hunting

This species is a powerful hunter, taking birds and mammals in a variety of woodland habitats, often utilizing a combination of speed and obstructing cover to ambush birds and mammals. Goshawks are often seen flying along adjoining habitat types, such as the edge of a forest and meadow; flying low and fast hoping to surprise unsuspecting prey. They are usually opportunistic predators, as are most birds of prey. The most important prey species are small mammals and birds found in forest habitats, in North America, this comprises largely grouse, American crow, snowshoe hare, and red squirrel. Compared to many smaller Accipiter species, northern goshawks are less specialized as predators of birds, with up to 69% or as little as 18 – 21% of their diet comprising either birds or mammals depending on location.[16][17][18] Prey species may be quite diverse, including pigeons and doves, pheasants, partridges, grouse, gulls, assorted waders, woodpeckers, corvids, waterfowl (mostly tree-nesting varieties such as the Aythya genus[16]) and various passerines depending on the region. Mammal prey may include rabbits, hares, tree squirrels, ground squirrels, chipmunks, rats, voles, mice, weasels, shrews, and bats.[19] Prey is often smaller than the hunting hawk, with an average prey mass of 275 g (9.7 oz) in one study of nesting birds in Minnesota.[16] In the Netherlands, male prey averaged 277 g (9.8 oz) whereas female prey averaged 505 g (17.8 oz).[9] However, northern goshawks will also occasionally kill much larger animals, up to the size of geese, raccoons, foxes and large hares, any of which can be more than twice their own weight.[9][20] The goshawk is likely a significant predator of other raptors, known prey including European honey buzzards, owls, smaller Accipiters and the American kestrel.[9][21]

Northern goshawks sometimes cache prey on tree branches or wedged in a crotch between branches for up to 32 hours. This is done primarily during the nestling stage.[14]

Behaviour

_'Just_missed_him'.png)

In the spring breeding season, northern goshawks perform a spectacular "undulating flight display", and this is one of the few times this secretive forest bird engages in behavior conspicuous to human observation. At this time, the surprisingly gull-like call of this bird is sometimes heard. As in all Accipiters, communication is primarily vocal since visual displays are difficult in the species' preferred densely vegetated habitats.[15] Adults defend their territories fiercely from all intruders, including passing humans. It is presumed that their unusually aggressive nest defense is an adaptation to defense against tree-climbing bears such as the American black bear and the Asian black bear. Additional predators at the nest may include formidable species that can climb or fly to trees such as fishers, other martens, wolverines, eagles and great horned owls and Eurasian eagle owls.[14][15] Gray wolves have been recorded stalking and killing fledging goshawks, especially when larger prey is scarce.[15] Goshawks are most under threat from hatching until their fledgling stage, and are rarely threatened by other wild animals outside their own species when adult. Other raptor species have been recorded as being viciously attacked by goshawks variously over competition for food, for too closely approaching active nests and in territorial behavior, and many are regularly displaced or even killed by the aggressive goshawk.[9][15] The northern goshawk is considered a secretive raptor, and is rarely observed even in areas where nesting sites are relatively close together. During nesting, the home ranges of goshawk pairs are from 1,500 to 10,000 acres (610 to 4,050 ha).[15]

Breeding

Adults return to their nesting territories by March or April and begin laying eggs in April or May. Usually, once they are "paired up", a breeding pair will mate for life. Territories often encompass a variety of habitats; however, the immediate nest area is often found in a large, mature or old-growth forest tree. Nests are bulky structures, often measuring about 1 m (3.3 ft) in both width and depth, made of dead twigs, lined with leafy green twigs or bunches of conifer needles and pieces of bark. The clutch size is usually 2 to 4, but anywhere from 1 to 5 eggs may be laid. Each egg is laid at 2- to 3-day intervals. The eggs are bluish-white and roughly-textured. They average 59 mm × 45 mm (2.3 in × 1.8 in) in size and weigh about 60 g (2.1 oz). The female is the primary incubator although the male will sometimes take a shift to give the female a chance to eat. The male does most of the hunting for both the female and the young at the nest. The incubation period can range from 28 to 38 days. Nestling goshawks are highly vocal. They may use a "whistle-beg" call as a plea for food. It begins as a ke-ke-ke noise, and progresses to a kakking sound. The chick may also use a high pitched "contentment-twitter" when it is well fed. The young leave the nest after from 35 to 46 days and start trying to fly another 10 days later. Parent goshawks continue to actively feed their offspring until they are about 70 days of age. The young may remain in their parents' territory for up to a year of age, at which point sexual maturity is reached.[15]

Status

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the northern goshawk was extirpated in the 19th century because of specimen collectors and persecution by gamekeepers, but in recent years it has come back by immigration from Europe, escaped falconry birds,[22] and deliberate releases.[23] The goshawk is now found in considerable numbers in Kielder Forest, Northumberland, which is the largest forest in Britain. The main threat to northern goshawks internationally today is the clearing of forest habitat on which both they and their prey depend.

In North America, several non-governmental conservation organizations petitioned the Department of Interior, United States Fish & Wildlife Service (1991 & 1997) to list the goshawk as "threatened" or "endangered" under the authority of the Endangered Species Act. Both petitions argued for listing primarily on the basis of historic and ongoing nesting habitat loss, specifically the loss of old-growth and mature forest stands throughout the goshawk's known range. In both instances, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service concluded that listing was not warranted, but state and federal natural resource agencies responded during the petition process with standardized and long-term goshawk inventory and monitoring efforts, especially throughout U.S. Forest Service lands in the Western U.S. The United States Forest Service (US Dept of Agriculture) has listed the goshawk as a "sensitive species", while it also benefits from various protection at the state level. In North America, the goshawk is federally protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 by an amendment incorporating native birds of prey into the Act in 1972. The northern goshawk is also listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).[24]

Subspecies A. gentilis laingi, found on Haida Gwaii and Vancouver Island, is listed as threatened in Canada.[25]

In falconry

The name "goshawk" is a traditional name from Anglo-Saxon gōshafoc, literally "goose hawk".[26] The name implies prowess against larger quarry such as wild geese, but were also flown against crane species and other large waterbirds. The name "goose hawk" is somewhat of a misnomer, however, as the traditional quarry for goshawks in ancient and contemporary falconry has been rabbits, pheasants, partridge, and medium-sized waterfowl. A notable exception is in records of traditional Japanese falconry, where goshawks were used more regularly on goose and crane species.[27] In ancient European falconry literature, goshawks were often referred to as a yeoman's bird or the "cook's bird" due to their utility as a hunting partner catching edible prey, as opposed to the peregrine falcon, also a prized falconry bird, but more associated with noblemen and less adapted to a variety of hunting techniques and prey types found in wooded areas. The northern goshawk has remained equal to the peregrine falcon in its stature and popularity in modern falconry.[28]

Goshawk hunting flights in falconry typically begin from the falconer's gloved hand, where the fleeing bird or rabbit is pursued in a horizontal chase. The goshawk's flight in pursuit of prey is characterized by an intense burst of speed often followed by a binding manoeuvre, where the goshawk, if the prey is a bird, inverts and seizes the prey from below. The goshawk, like other accipiters, shows a marked willingness to follow prey into thick vegetation, even pursuing prey on foot through brush.[28]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2013). "Accipiter gentilis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ "Astur gentilis schvedowi AVIS-IBIS".

- ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. (in Latin). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 89.

F. cera pedibusque flavis, corpore cinereo maculis fuscis cauda fasciis quatuor nigricantibus

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 346.

- ↑ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie; ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, espéces & leurs variétés (in French). Volume 1. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. pp. 28, 310.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 323.

- ↑ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 30, 171–172. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ "Northern Goshawk". Birds of Quebec. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. Illustrated by Kim Franklin, David Mead & Philip Burton. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-12762-3.

- 1 2 "Northern Goshawk". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ Johnson, Donald R. (1989). "Body size of Northern Goshawks on coastal islands of British Columbia" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 101 (4): 637–639.

- ↑ "Northern Goshawk – Accipiter gentilis". AVIS-IBIS: Birds of Indian Subcontinent. 4 December 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ "Northern Goshawk". Hanging Rock Raptor Observatory. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Johnsgard, P. (1990). Hawks, Eagles, & Falcons of North America. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 0874746825.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Squires, J.; Reynolds, R. (1997). Northern Goshawk. Birds of North America. 298. pp. 2–27.

- 1 2 3 Smithers, B.L.; Boal, C.W.; Andersen, D.E. (2005). "Northern Goshawk diet in Minnesota: An analysis using video recording systems" (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 39 (3): 264–273.

- ↑ Lewis, Stephen B.; Titus, Kimberly; Fuller, Mark R. (2006). "Northern Goshawk Diet During the Nesting Season in Southeast Alaska" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 70 (4): 1151–1160. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1151:NGDDTN]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "Accipiter gentilis – northern goshawk". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan.

- ↑ Mikula, P.; Morelli, F.; Lučan, R. K.; Jones, D. N.; Tryjanowski, P. (2016). "Bats as prey of diurnal birds: a global perspective". Mammal Review. doi:10.1111/mam.12060.

- ↑ Frost, P. "Northern Goshawk (Accipter gentilis)". pauldfrost.co.uk.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael, ed. (2010). "American Kestrel". Encyclopedia of Earth. Cleveland: U.S. National Council for Science and the Environment.

- ↑ Morrison, Paul (1989). Bird Habitats of Great Britain and Ireland: A New Approach to Birdwatching. London, UK: Michael Joseph, Ltd. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-7181-2899-9.

- ↑ Kenward, Robert (2006). The Goshawk. London, UK: T & A D Poyser. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-7136-6565-9.

- ↑ Woodbridge, B.; Hargis, C.D. (2006). Northern goshawk inventory and monitoring technical guide (PDF). General Technical Report WO-71 (Report). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

- ↑ "Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis)". Status of Birds in Canada. Government of Canda. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Lockwood, W.B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-866196-2.

- ↑ Jameson, E.W., Jr. (1962). The Hawking of Japan, the History and Development of Japanese Falconry. Davis, California. p. 2.

- 1 2 Beebe, F.L.; Webster, H.M. (2000). North American Falconry and Hunting Hawks (8th ed.). ISBN 0-685-66290-X.

Further reading

Identification

- Vinicombe, Keith (2005). "Getting to grips with goshawks". Birdwatch. 153: 29–33.

Historical material

- "Falco atricapillus, Ash-coloured or Black-cap Hawk"; from American Ornithology 2nd edition, volume 1 (1828) by Alexander Wilson and George Ord. Colour plate from 1st edition by A. Wilson.

- John James Audubon. "The Goshawk", Ornithological Biography volume 2 (1834). "Goshawk" (note in Appendix), Ornithological Biography volume 5 (1839). "The Goshawk" (with illustration), Birds of America octavo edition, 1840.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Accipiter gentilis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Accipiter gentilis |

- "Northern goshawk media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Northern goshawk species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Northern goshawk - Accipiter gentilis – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 5.4 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Feathers of Northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis)

- "Accipiter gentilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- BirdLife species factsheet for Accipiter gentilis

- "Accipiter gentilis". Avibase.

- Audio recordings of Northern goshawk on Xeno-canto.