Novantae

The Novantae were a people of the late 2nd century who lived in what is now Galloway and Carrick, in southwestern-most Scotland. They are mentioned briefly in Ptolemy's Geography (written c. 150), and there is no other historical record of them. Excavations at Rispain Camp, near Whithorn, show that it was a large fortified farmstead occupied between 100 BC and 200 AD, indicating that the people living in the area at that time were engaged in agriculture.

Their ethnic and cultural affinity is uncertain, with various authorities positing different links, beginning with Bede, who referred to the Novantae as the Niduarian Picts,[1] and including the Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.), which described them as “a tribe of Celtic Gaels called Novantae or Atecott Picts.”[2] Scottish author Edward Grant Ries has identified the Novantae (along with other early tribes of southern Scotland) as a Brythonic-speaking culture.[3] However, the region has a history that includes the culture of the Gaels, Picts, and Brythonic speakers at various times, alone and in combination, and there is not enough information to make conclusions about the ethnicity of the Novantae..

Ptolemy

The only reliable historical reference to the Novantae is from the Geography of Ptolemy in c. 150, where he gives their homeland and primary towns.[4] They are found in no other source.

They are unique among the peoples that Ptolemy names in that their location is reliably known due to the way he named several readily identifiable physical features. His Novantarum Cheronesus is the Rhins of Galloway, and his Novantarum promontory is the Mull of Galloway. This pins the Novantae to that area. Ptolemy says that their towns were Locopibium and Rerigonium. As there were no towns as such in the area at that time, he was likely referring to native strong points such as duns or royal courts.

Roman era

The earliest reliable information on the region of Galloway and Carrick when it was inhabited by the Novantae comes from archaeological discoveries. They lived in small enclosed settlements, most of them less than a single hectare in area and inhabited from the 1st millennium BC through to the Roman era. They also constructed hillforts and a small number of crannogs and brochs. Stone-walled huts appear during the Roman era and the Novantae are thought to have had a centre of some kind at Clatteringshaws near Kirkcudbright, which started out as a pallisaded enclosure before being expanded into a set of timber and then stone-faced ramparts. This had been abandoned by the Roman period but there is evidence that the Romans used it as the target of a military exercise, erecting two practice camps nearby and subjecting it to a mock siege.[5]

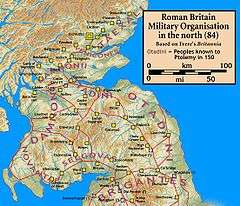

The only Roman military presence was a small fortlet at Gatehouse of Fleet, in the southeastern part of Novantae territory.[6] The Roman remains that have been excavated are portable, such as might be carried or transported into the region. The absence of evidence of Roman presence is in sharp contrast to the many remains of native habitation and strong points.[7][8] Rispain Camp near Whithorn, once thought to be Roman, is now known to be the remains of a large fortified farmstead, occupied by natives before and during the Roman Era.[9]

In his account of the campaigns of Gnaeus Julius Agricola (governor 78 – 84), Tacitus offers no specific information on the peoples then living in Scotland. He says that after a combination of force and diplomacy quieted discontent among the Britons who had been conquered previously, Agricola built forts in their territories in 79. In 80 he marched to the Firth of Tay, campaigning against the peoples there. He did not return until 81, at which time he consolidated his gains in the lands that he had conquered.[10] The Novantae were later said to have caused trouble along Hadrian's Wall, and the Gatehouse of Fleet fortlet was presumably used to subdue them.[5]

Novant

The Novantae disappear from the historical record after the end of the Roman occupation, with their territory supplanted by the kingdoms of Rheged and Gododdin.[5] A kingdom called Novant appears in the medieval Welsh poem Y Gododdin, attributed to Aneirin. The poem commemorates the Battle of Catraeth, in which an army raised by Gododdin attempted an ill-fated raid on the Angles of Bernicia. The work elegises the various warriors who fought alongside the Gododdin, among them the "Three Chiefs of Novant" and their substantial retinue.[11] This Novant is evidently related to the Novantae tribe of the Iron Age.[12]

Contradicting Ptolemy

Ptolemy's placement of the Selgovae town of Trimontium was accepted to be somewhere along the southern coast of Scotland until William Roy (1726–1790) placed it far to the east at Eildon Hills, near Newstead. Roy was trying to follow an itinerary given in the 1757 De Situ Britanniae, and moving Ptolemy's Trimontium made the itinerary seem more logical according to his historical work, Military Antiquities of the Romans in North Britain (1790, published posthumously in 1793). Roy did not alter Ptolemy's placement of the Selgovae in southern Scotland, but chose to assign Trimontium to a different people who were described in De Situ Britanniae.[13]

When De Situ Britanniae was debunked as a fraud in 1845, Roy's misguided placement of Trimontium was retained by some historians, though he was no longer cited for his contribution. Furthermore, some historians not only accepted Roy's placement of Trimontium, but also returned the town to the Selgovae by moving their territory such that they would be near Eildon Hills. Ptolemy's placement of the Novantae in Galloway was retained, and since Ptolemy said that they were adjacent to the Selgovae, Novantae territory was greatly expanded beyond Galloway to be consistent with this thesis, which survives in a number of modern histories.[14]

The result is that an 'error correction' to the sole legitimate historical reference (Ptolemy), made so that a fictional itinerary in De Situ Britanniae would seem more logical, is retained; and the sole legitimate historical reference is further 'corrected' by moving the Selgovae far from their only known location, greatly expanding Novantae territory in the process.

While Roy's historical work is largely ignored due to his unknowing reliance on a fraudulent source, his maps and drawings are untainted, and continue to be held in the highest regard.

Treatment by historians

Befitting the single historical mention of the Novantae by Ptolemy, many historians have largely included the Novantae im passim in their works, if they are mentioned at all. William Forbes Skene (Celtic Scotland, 1886) briefly relates their notice in Ptolemy, adding his conjectures as to the possible locations of towns, though not with any conviction.[15] John Rhys (Celtic Britain, 1904) mentions the Novantae in passing, without any detailed discussion.[16] Local Galwegian historians, writing histories of their own home territory, provide a similarly scant treatment.[17][18][19][20]

More recent histories largely treat the Novantae in passing, but often weave them into a story that is not supported by either Ptolemy's map or archaeological evidence. John Koch (Celtic Culture, 2005) doesn't discuss the Novantae directly, but associates their name with the Trinovantes of southeastern England, and provides a map showing the "Novant" occupying Galloway and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright to accompany his discussion of the Gododdin.[21] Barry Cunliffe, an archaeologist, (Iron Age Communities in Britain, 1971) mentions the Novantae in passing, saying their homeland was Galloway and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, and with a map showing it, which he attributes to "various sources".[22] David Mattingly (An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 2006) mentions them as a people of southwestern Scotland according to Ptolemy, with maps showing them as occupying both Galloway and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright.[23] Sheppard Frere (Britannia: A History of Roman Britain, 1987) mentions the Novantae several times in passing, associating them firmly with the Selgovae and sometimes with the Brigantes. He places them in both Galloway and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, with the Selgovae on the other side of the Southern Uplands in southeastern Scotland.[24] The Novantae are inconsequential to the larger history of Scotland in Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History (2005) by Alistair Moffat, but he weaves a number of colourful though questionable details about them into his story. He says that their name means 'The Vigorous People', that they had kings and often acted in concert with the Selgovae and Brigantes, all of whom may have joined the Picts in raids on Roman Britain.[25] He provides no authority for any of these assertions.

See also

Citations

- ↑ Rhys, John (1904). Celtic Britain (3rd ed.). London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 223. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge: University Press. 1911. p. 832. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Ries, Edward Grant. "Scotland during the Roman Empire". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Ptolemy & 150, Geographia 2.2, Albion Island of Britannia.

- 1 2 3 Sassin, Anne (2008). Snyder, Christopher A., ed. Early People of Britain and Ireland: An Encyclopedia, Volume II. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-84645-029-7.

- ↑ Frere 1987:88–89, 112–113, 130–131, 142–143, 347–348, Britannia

- ↑ Maxwell 1891:8–9, Roman Remains, A History of Dumfries and Galloway

- ↑ M'Kerlie 1877:1–2, Wigtonshire.

- ↑ Harding 2004:62. Reports on the excavations were published in 1983.

- ↑ Tacitus & 98:364–368, Life of Agricola, Chapters 19 – 23.

- ↑ Skene 1868:380–381, XVIII, The Gododdin

- ↑ Koch 1997:lxxxii–lxxxiii

- ↑ Roy 1790:115–119, Military Antiquities, Book IV, Chapter III

- ↑ Cunliffe 1971:216 – see, for example, the influential Iron Age Communities in Britain, map of the tribes of Northern Britain, attributed to "various sources"

- ↑ Skene 1886:72, Celtic Scotland

- ↑ Rhys 1904:222, 223, 227, 232, Celtic Britain

- ↑ Agnew 1891:1,1 2, 10, 41, The Hereditary Sheriffs of Galloway

- ↑ Maxwell 1891:2, 3, 4, 7, 10, 14,23, A History of Dumfries and Galloway

- ↑ M'Kerlie 1877:14, 15, 22–25, 27, 28, 31, 36, 71, History of the Lands and their Owners in Galloway

- ↑ M'Kerlie 1891:14–17, Galloway in Ancient and Modern Times, Ptolemy's Geography.

- ↑ Koch 2005:824, 825, 1689, Celtic Culture, Gododdin and Trinovantes.

- ↑ Cunliffe 1971:215–216, Iron Age Communities in Britain, Southern Scotland: Votadini, Novantae, Selgovae and Damnonii.

- ↑ Mattingly 2006:49, 148, 423, 425, An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire

- ↑ Frere 1987:42, 90, 92, 93, 107, 111, 134, 355, Britannia

- ↑ Moffat 2005:212, 231, 248, 272, 275, 277, 279, 280, 302, 306, Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History

References

- Agnew, Andrew (1891), Agnew, Constance, ed., The Hereditary Sheriffs of Galloway, I (2 ed.), Edinburgh: David Douglas (published 1893)

- Bertram, Charles (1757), Hatcher, Henry, ed., The Description of Britain, Translated from Richard of Cirencester, London: J. White and Co (published 1809)

- Cunliffe, Barry W. (1971), Iron Age Communities in Britain (4th ed.), Routledge (published 2005), p. 216, ISBN 0-415-34779-3

- Frere, Sheppad Sunderland (1987), Britannia: A History of Roman Britain (3rd, revised ed.), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-1215-1

- Harding, Dennis William (2004), "The Borders and southern Scotland", The Iron Age in northern Britain: Celts and Romans, natives and invaders, Routledge, p. 62, ISBN 0-415-30149-1

- Koch, John T., ed. (1997), The Gododdin of Aneirin: Text and Context from Dark-Age North Britain, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-1374-4

- Koch, John T., ed. (2005), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABL-CLIO (published 2006), ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0

- Mattingly, David (2006), An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, London: Penguin Books (published 2007), ISBN 978-0-14-014822-0

- Maxwell, Herbert (1891), A History of Dumfries and Galloway, Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons (published 1896)

- Moffat, Alistair (2005), Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History, New York: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-28795-8

- M'Kerlie, Peter Handyside (1877), "General History", in M'Kerlie, Immeline M. H., History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway With Historical Sketches of the District, I (2 ed.), Paisley: Alexander Gardner (published 1906)

- M'Kerlie, Peter Handyside (1891), Galloway in Ancient and Modern Times, Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons

- Ptolemy (c. 140), Thayer, Bill, ed., Geographia, Book 2, Chapter 2: Albion island of Britannia, LacusCurtius website at the University of Chicago (published 2008), retrieved 26 April 2008 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Rhys, John (1904), Celtic Britain (3rd ed.), London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

- Roy, William (1790), "Military Antiquities of the Romans in North Britain", Digital Library, National Library of Scotland (published 2007)

- Skene, William Forbes (1868), The Four Ancient Books of Wales, I, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, pp. 380–381

- Skene, William Forbes (1886), Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban (History and Ethnology), I (2nd ed.), Edinburgh: David Douglas

- Tacitus, Cornelius (98), "The Life of Cnaeus Julius Agricola", The Works of Tacitus (The Oxford Translation, Revised), II, London: Henry G. Bohn (published 1854), pp. 343–389 Check date values in:

|date=(help)