Nueva Canción Chilena

| Nueva canción Chilena | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Latin American, folk music, Guitar music, Andean music |

| Cultural origins | Chilean culture, Music and politics |

| Typical instruments | bass guitar, charango, drums, guitar and pan flute |

| Regional scenes | |

| Argentina; Brazil; Bolivia; Chile; Colombia; Cuba; Mexico; Nicaragua; Paraguay; Peru; Portugal; Spain; Uruguay; Venezuela | |

The Nueva Canción Chilena or "New Chilean Song” was a movement and genre of Chilean traditional and folk music incorporating strong political and social themes. The movement was to spread throughout Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s, in what is called "Nueva canción" sparking a renewal in traditional folk music and playing a key role in political movements in the region.

The foundations of the Chilean New Song were laid through the efforts of Violeta Parra to revive over 3,000 Chilean songs, recipes, traditions, and proverbs,[1] and it eventually aligned with the 1970 presidential campaign of Salvador Allende, incorporating the songs of Víctor Jara, Inti-Illimani and Quilapayun among others.

Other key proponents of the movement include Patricio Manns, Rolando Alarcón, Payo Grondona, Patricio Castillo, Homero Caro, and Kiko Álvarez, as well as non-Chilean musicians, such as César Isella and Atahualpa Yupanqui from Argentina and Paco Ibañéz of Spain.

History

The Chilean New Song movement was spurred by a renewed interest in Chilean traditional music and folklore in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Folk singers such as Violeta Parra and Víctor Jara traversed the regions of Chile both collecting traditional melodies and songs and seeking inspiration to create songs with social themes. These songs diverged from songs known in the cities at the time, which were often stylized interpretations of central Chilean folk music that emphasized patriotism and idyllic representations of country life; in contrast, the New Song sought to give a voice to Chile’s rural peoples, its working class, and their realities.[2][3] Early musicians in the movement often used folk instruments such as the quena (Andean flute) or zampoñas (pan-pipes).[4] This phase of the Chilean New Song has been referred to as the “discovery and protest” phase.[5]

Violeta Parra in particular played a key role in this phase of the New Song as she was committed to reviving Chilean traditional songs and bringing a voice to the Chilean poor. In the 1960s, Parra founded La Peña de Los Parra in Santiago alongside her son Ángel Parra, also a key figure in the movement, and this became a meeting place for musicians of the New Song. Parra’s impact on the movement is widely acknowledged.[6] In 1981, Cuban singer Silvio Rodríguez remarked that her influence on the Latin American New Song movement cannot be understated: “Violeta is fundamental. Nothing would have been as it is had it not been for Violeta”.[7]

Rejection of foreign influence on Chilean culture, particularly US culture, further stimulated the movement as it sought to create a sense of Chilean national identity.[8] At the inaugural Festival de la Nueva Canción Chilena (Festival of the Chilean New Song) in 1969 in Santiago - the first time the movement was so named - Universidad Catolica rector Fernando Castillo said:

“Perhaps popular song is the art that best defines a community. But lately in our country we are experiencing a reality that is not ours… Our purpose here today is to search for an expression that describes our reality…[9] How many foreign singers come here and get us all stirred up, only to leave us emptier than ever when they leave? And isn’t it true that our radio and television programs seldom encourage the creativity of our artists… ? Let our fundamental concern be that our own art be deeply rooted in the Chilean spirit so that when we sing - be it badly or well - we express genuine happiness and pain, happiness and pain that are our own.”

The Chilean New Song also developed amidst a background of social upheaval taking place throughout Latin America. The Cuban Revolution and the Vietnam War provided inspiration for a growing number of musicians who aligned themselves politically with the socialist struggle. Examples of this include Víctor Jara's Zamba del Che in homage to Che Guevara and Rolando Alarcón's Por Cuba y Por Vietnam.[10] Following Violeta Parra’s death in 1967, Víctor Jara became one of the leading figures of the movement.

In Chile, the New Song came to actively support the presidential campaign of Salvador Allende. Folk singers of the movement wrote songs in support of Allende’s Popular Unity coalition, playing at political rallies and becoming cultural beacons of the left.[11]

The campaign hymn for Popular Unity, "Venceremos" (“we shall succeed”), written by Claudio Iturra and Sergio Ortega and performed by the band Inti-Illimani, contained lyrics urging the Chilean people to unite behind Allende's. Another key song in the movement, El pueblo unido jamas sera vencido (“the people united will never be defeated”), written by Quilapayún and Sergio Ortega, was also originally composed in support of Allende’s electoral campaign and went on to become an internationally recognised song of protest.

The election of Salvador Allende as Chilean president in 1970 heralded a new phase for the New Song movement and themes became less tied to a particular political cause.,[12][13] In one of his final songs, Manifesto, Víctor Jara sung of the essence of the New Song:

My guitar is not for the rich

no, nothing like that.

My song is of the ladder

we are building to reach the stars.

For a song has meaning

when it beats in the veins

of a man who will die singing,

truthfully singing his song.

The 1973 military coup led by Augusto Pinochet marked the end of the Chilean New Song movement. Many of its proponents were captured and tortured and fled Chile in exile. In the days following the coup, Víctor Jara was taken to Chile Stadium (Estadio Chile now Estadio Víctor Jara), tortured and killed at the hands of the military regime. According to testimony, he was tortured by soldiers who broke his hands and taunted him saying “sing now, if you can, bastard”; Jara reportedly responded by singing a verse of Venceremos and was subsequently taken away and killed.[14][15] Jara's final work was a poem without a title, commonly named Estadio Chile, wherein he wrote of the conditions of those captured by the military junta:

How hard it is to sing

when I must sing of horror.

Horror which I am living,

horror which I am dying.

To see myself among so much

and so many moments of infinity

in which silence and screams

are the end of my song.[1]

- ^ Tapscott, Stephen (1996). Twentieth-Century Latin American Poetry: A Bilingual Anthology. University of Texas Press (1 ed.). Texas, US. p. 337.

From foreign shores, a number of New Song musicians including Angel Parra,[16] Patricio Manns and bands Inti-Illimani and Quilapayun continued to perform in the New Song style.

List of artists

- Amerindios

- Ángel Parra

- Congreso

- Eduardo Carrasco

- Francesca Ancarola

- Guillermo "Willy" Oddó

- Horacio Salinas

- Illapu

- Inti-Illimani

- Isabel Parra

- Julio Numhauser

- Los Jaivas

- Luis Advis

- Margot Loyola

- Max Berrú

- Patricio Castillo

- Patricio Manns

- Quilapayún

- Rodolfo Parada

- Rolando Alarcón

- Santiago del Nuevo Extremo

- Sergio Ortega

- Silvia Urbina

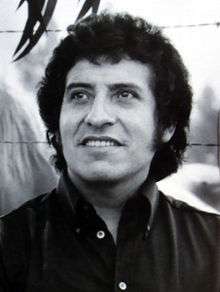

- Víctor Jara

- Violeta Parra

See also

References

- ↑ Verba, Erika (2007). Studies in Latin American Popular Culture "Violeta Parra, Radio Chilena, and the 'Battle in Defense of the Authentic' during the 1950s in Chile". (1 ed.). Santiago, Chile. pp. 65–156. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Mularski, Jedrek. Music, Politics, and Nationalism in Latin America: Chile During the Cold War Era. Amherst: Cambria Press. ISBN 9781604978889.

- ↑ Nueva canción chilena (ES) 2006 - 2014 http://www.musicapopular.cl/ retrieved on October 13, 2014

- ↑ "The 1970 victory of the Popular Unity government led by Salvador Allende in Chile marked the rise of the first democratically elected socialist government in Latin America. After years of social and political unrest, the election of the Allende government was seen as a beacon of hope by the Left, both in Chile and throughout the region. As the new president-elect took the stage to greet cheering citizens, a banner above his head read, "You Can't Have a Revolution Without Songs." It was a powerful statement about the role of music in social and political change that had fueled the emerging popular musical movement in South America known as nueva canción (New Song Movement)." The New Song movement in South America Smithsonian Folkways. www.folkways.si.edu retrieved on October 13, 2014

- ↑ Taffet, J. F. (2007). The new chilean song movement and the politics of culture. Journal of American Culture (1 ed.). Santiago, Chile. pp. 20, 2, 91–103.

- ↑ Morris, Nancy (1986). ""Canto Porque es Necesario Cantar: The New Song Movement in Chile" (PDF). Latin American Studies Association 21 (2): 117–36. Santiago, Chile. p. 21 (2): 117–36 91–103.

- ↑ Krebs Merino, Patricio; Corces, Juan Ignacio (1986). "Entrevista exclusiva: Silvio Rodriguez". La Bicicleta. Santiago, Chile. p. 24.

- ↑ Morris, Nancy (1986). ""Canto Porque es Necesario Cantar: The New Song Movement in Chile" (PDF). Latin American Studies Association 21 (2): 117–36. Santiago, Chile. p. 21 (2): 117–36.

- ↑ Morris, Nancy (1986). ""Canto Porque es Necesario Cantar: The New Song Movement in Chile" (PDF). Latin American Studies Association 21 (2): 117–36. Santiago, Chile. p. 21 (2): 120.

- ↑ "LA NUEVA CANCIÓN CHILENA. EL PROYECTO CULTURAL POPULAR Y LA CAMPAÑA PRESIDENCIAL Y GOBIERNO DE SALVADOR ALLENDE" Pensamiento Crítico ISSN 0717-7224 Claudio Rolle, Retrieved on October 14, 2014

- ↑ Taffet, J. F. (2007). The new chilean song movement and the politics of culture. Journal of American Culture (1 ed.). Santiago, Chile. pp. 20, 2, 91–103.

- ↑ Taffet, J. F. (2007). The new chilean song movement and the politics of culture. Journal of American Culture (1 ed.). Santiago, Chile. pp. 20, 2, 91–103.

- ↑ La nueva canción Chilena (ES) Author: Fernando Barraza, Title: "La Nueva Canción Chilena", from the series "Nosotros los chilenos" (we the Chileans). Edit. Quimantú - 1972, Santiago

- ↑ Taffet, J. F. (2007). The new chilean song movement and the politics of culture. Journal of American Culture (1 ed.). Santiago, Chile. pp. 20, 2, 91–103.

- ↑ La nueva cancion Chilena (ES) Author: Fernando Barraza, Title: "La Nueva Canción Chilena", from the series "Nosotros los chilenos" (we the Chileans). Edit. Quimantú - 1972, Santiago

- ↑ Angel Parra Biography (ES) Ángel Parra ya era parte activa de un movimiento que, más que ideológico, concibía —en sus palabras— al canto "puesto al servicio de un ideal, de una utopía". http://www.musicapopular.cl retrieved on October 14, 2014

Further reading

- LA NUEVA CANCIÓN CHILENA. EL PROYECTO CULTURAL POPULAR Y LA CAMPAÑA PRESIDENCIAL Y GOBIERNO DE SALVADOR ALLENDE, Claudio Rolle.

- "Socially conscious music forming the social conscience: Nicaraguan Musica Testimonial and the creation of a revolutionary moment" by T.M. Scruggs; in From tejano to tango: Latin American popular music edited by Walter Aaron Clark.

- Music, Politics, and Nationalism in Latin America: Chile During the Cold War Era by Jedrek Mularski.

.jpg)