Orlan

| ORLAN | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Mireille Suzanne Francette Porte May 30, 1947 Saint-Étienne, France |

| Website |

www |

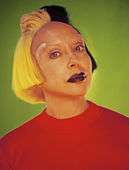

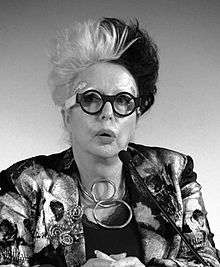

Orlan (born Mireille Suzanne Francette Porte)[1][2][3] is a French artist, born May 30, 1947 in Saint-Étienne, Loire.[4][5][6] She adopted the name Orlan in 1971, which she always writes in capital letters : "ORLAN".[7] She lives and works in Los Angeles, New York, and Paris. She was invited to be a scholar in residence at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, for the 2006-2007 academic year.[8] She sits on the board of administrators for the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and is a professor at the École nationale supérieure d'arts de Cergy-Pontoise.

Although Orlan is best known for her work with plastic surgery in the early to mid-1990s, she has not limited her work to a particular medium.

About her importance in art history as a body artist, in "The Narrative" monograph (2007):

– "Revisiting Orlan’s history, from the early sixties to the present day, means, above all, rediscovering the history of the poetics of the body, in which body art and carnal art[9] are the fundamental stages. Real body and imaginary body, lived body and emotional body, mystic body and social body, diffuse body and hybrid body, all merge together in the ceaseless flow of references in Orlan’s work."[10]

Biography

Early works

In 1964, while in her home town of Saint-Étienne, she started the "Marches au ralenti" ("Slow motion walks"), in which she would walk as slowly as possible between two central parts of the city.

From 1965, she performed the "MesuRages", in which she would use her own body as a measuring instrument, called the "Orlan-body". In this performance, she would measure how many people could fit within a given architectural space, using her "Orlan-body" as a unit of measurement.[11]

In the "MesuRages," and in later work, Orlan made great use of her "Trousseau". The sheets from her trousseau (a set of household goods and other items traditionally provided to a young woman by her family upon her marriage) were re-purposed by Orlan in a number of projects.[12]

From 1964 to 1966, Orlan made a series of photographic works known as the "Vintages." She destroyed the original negatives, and only one copy of each photograph remains. In this series, she posed naked in various yoga-like positions. One of the most famous pictures of this series is "Orlan accouche d'elle m'aime."

From 1967 to 1975, she undertook a new series, the "Tableaux Vivants."

In 1971 she "baptized herself" Sainte-Orlan.[13]

In 1977, her performance "The Artist’s Kiss" (Le baiser de l'artiste), during the FIAC in Paris, became a huge scandal. Outside the Grand Palais, a life-size photo of her torso was turned into a slot machine. After inserting a coin, one could see it descending to the groin, and then was awarded a kiss from the artist, who stood on a pedestal behind it.

In 1978, she created "Documentary Study: The Head of Medusa," which took place at the Museum Ludwig, Aachen. The motto of the performance was Freud’s quotation on the Head of Medusa: "at the sight of the vulva, even the devil runs away.” The artist displayed her sexual organs under a magnifying glass during menstruation.

In 1978, she founded the International Symposium of Performance in Lyon.

In 1982, she created the first online magazine of contemporary art, Art-Accès-Revue, on France's precursor to the Internet, the Minitel.

The Reincarnation of Saint-Orlan

The Reincarnation of Saint-Orlan, a new project that started in 1990, involves a series of plastic surgeries through which the artist transformed herself into elements from famous paintings and sculptures of women. As a part of her 'Carnal Art' manifesto, these works were filmed and broadcast in institutions throughout the world, such as the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Sandra Gehring Gallery in New York.[14] Orlan's goal in these surgeries is to acquire the ideal of female beauty as depicted by male artists. When the surgeries are complete, she will have the chin of Botticelli’s Venus, the nose of Jean-Léon Gérôme's Psyche, the lips of François Boucher’s Europa, the eyes of Diana (as depicted in a 16th-century French School of Fontainebleu painting), and the forehead of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Orlan picked these characters “not for the canons of beauty they represent... but rather on account of the stories associated with them." Orlan chose Diana, because she is inferior to the gods and men, but is leader of the goddesses and women; Mona Lisa, because of the standard of beauty, or anti-beauty, that she represents; Psyche, because of the fragility and vulnerability within her soul; Venus, for carnal beauty; and Europa, for her adventurous outlook on the future.[15]

Instead of condemning cosmetic surgery, Orlan embraces it;[16] instead of rejecting the masculine, she incorporates it; and instead of limiting her identity, she defines it as “nomadic, mutant, shifting, differing.” Orlan has stated: “my work is a struggle against the innate, the inexorable, the programmed, Nature, DNA (which is our direct rival as far as artists of representation are concerned), and God!”.[17]

"I can observe my own body cut open, without suffering!... I see myself all the way down to my entrails; a new mirror stage... I can see to the heart of my lover; his splendid design has nothing to do with sickly sentimentalities... Darling, I love your spleen; I love your liver; I adore your pancreas, and the line of your femur excites me." (from Carnal Art manifesto)

"Sainte Orlan" came from a character that I created for "Le baiser de l'artiste" from a text called "Facing a society of mothers and merchants." The first line of this text was: “At the bottom of the cross were two women, Maria and Maria Magdalena.” These are two inevitable stereotypes of women that are hard to avoid: the mother and the prostitute. In “Le baiser de l'artiste” there were two faces. One was Saint Orlan, a cutout picture of me dressed as Madonna glued onto wood. One could buy a five francs church candle and I was sitting on the other side behind the mock-up of the vending machine. One could buy a French kiss from me for the same amount of money one could buy a candle. The idea was to play on the ambivalence of the woman figure and the desire of both men and women towards those biblical and social stereotypes. Being showcased in the Paris International Contemporary Art Fair, the artwork was somehow both an installation and a performance,"[18] said Orlan, in her interview with Acne Paper.

| Photographs of Orlan | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Recent works

Since 1994, Orlan has been creating a digital photographic series titled "Self-Hybridizations," where her face merges with past facial representations (masks, sculptures, paintings) of non-western civilizations. So far, three have been completed: Pre-Columbian, American-Indian and African.

In 2001, she orchestrated a series of filmic posters, "Le Plan du Film", with various artists and writers. The posters affirm the existence of films which do not actually exist. The posters question the notions of character and narrative reflected in the social reality of individual roles and stories.

In 2007, Orlan collaborated with the Symbiotica laboratory in Australia, resulting in the bio-art installation "The Harlequin's Coat".

Part of her on-going work includes "Suture/Hybridize/Recycle", a generative and collaborative series of clothing made from Orlan's wardrobe and focusing on suture: the deconstruction of past clothing reconstructed into new clothing that highlights the sutures.

Exhibitions (2000s)

- 2016

- FRAC Basse-Normandie, "ORLAN TODAY", curator Sylvie Froux, Caen, France

- Sungkok Art Museum, ORLAN-Techno-Body: A Retrospective, curator Soukyoun Lee, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2014

- Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, “ORLAN – The Icon of French Contemporary Art. Le plan du film and Other Scenarios”, Riga, Latvia

- 2011

- Nantes Fine Art Museum, Chapelle de l’Oratoire,the beef on the tongue, curators Blandine Chavanne and Alice Fleury, Nantes, France

- Pouchkine Museum, Dior, curators Florence Müller and Jacques Ranc, Moscow, Russia

- 2010

- Project room / La Cambre / Ecole Supérieure des Arts Visuels, Orlan Remix, Est-ce que vous êtes Belges? Ou les draps-peaux hybridés, organizer Johan Muyle, Brussels, Belgium

- Sheldon Museum of Art, Bodies, Technology, Fashion, curator Daniel J. Veneciano, Lincoln (Nebraska), USA

- State Museum of Centemporary Art of Thessaloniki, Isole Mai Trovate/Islands Never Found, curators Lorand Heygi and Katerina Koskina, Thessaloniki, Greece

- Guy Pieters Gallery, Coups de Coeur, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France

- Musée Bourdelle, En mai fais ce qu’il te plaît !, curator Juliette Laffon, Paris, France

- 2009

- São Paulo Museum of Art, Year of France in Brazil, Orlan+Campana+Neon, organizer Lisbeth Rebollo, São Paulo, Brazil

- Abbey of Maubuisson, Unions Mixtes, Mariages Libres et Noces Barbares, organizer Caroline Coll, Maubuisson, France

- Grand Palais, La Force de l’art, organizers Jean-Louis Froment, Jean-Yves Jouannais, Didier Ottinger, Paris, France

- Centre Georges Pompidou, elles@centrepompidou, organizer Camille Morineau, co-organizers Quentin Bajac, Cécile Debray, Valérie Guillaume and Emma Lavigne, Paris, France

- Casino Luxembourg, SK-interfaces, Exploring Borders in Art, Technology and Society, organizer Jens Hauser, Luxembourg

- Palazzo Franchetti, Glass Stress, organizer Laura Mattioli Rossi, Venice, Italy.

- Sungkok Art Museum, Masks, organizer Alain Sayag, Seoul, Korea.

- FIAC, Michel Rein Gallery, Paris, France

- 2008

- Espacio Artes Visuales, Suture Hybridization-recycling, in collaboration with Davidelfin, organizers Isabel Tejeda, Murcia, Espagne

- Michel Rein Gallery, Self-hybridation, American-Indians, Paris, France

- The Tallinn Art Hall, Orlan: Post identity strategies, organizers Eugenio Viola, Reet Varblane, Tallinn, Estonia

- The Vancouver Art Gallery, WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, organizer Connie Butler, Vancouver, Canada

- Chapel of the National School of Fine Arts, Académia who are you? organizer Axel Vervoordt, Paris, France

- Fact, Sk-Interfaces, organizer Jens Hauser, Liverpool, UK

- Museu Berardo, BESart – Colecçao Banco Espirito Santo, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2007

- Getty Research Institute, Skaï and Sky and Video, organizer Sabine Schlosser, Los Angeles, USA

- Museum of Modern Art of Saint-Etienne, The Narrative, organizers Lorand Hegyi and Viola Eugenio, Saint Etienne, France

- Beap 07, Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth Stillness, Perth, Australia

- KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Into Me / Out of Me, organizer Klaus Biesenbach, Berlin, Germany

- Kunstmuseum Ahlen, Diagnostic Art – Medicine in Contemporary Art, organizer Burkhard Leismann, Ahlen, Germany

- MOCA Geffen Los Angeles, Wack!, Art and the Feminist Revolution, organizer Connie Butler, Los Angeles, USA

- Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, 45 Años de Arte y Feminismo, Bilbao, Spain

- Osaka National Art Museum, Skin of / in Contemporary Art, organizer Yukihiro Hiroyoshi, Osaka, Japan

- Palazzo Fortuny, Artempo, organizers Jean-Hubert Martin and Tijs Visser, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy

- 2006

- Grand Palais, La Force de l'Art, organizer Eric Troncy, Paris, France

- Musée des Arts Modestes de Sète, Bang Bang, organizer Hervé di Rosa, Sète, France

- Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse Number 1, Transimages 4, organizer Anne-Marie Morice, Yokohama, Japan

- PS1, Into Me / Out of Me, organizer Klaus Biesenbach, New York, USA

- 2005

- Palais de Tokyo, Luminous Room, with the architect Philippe Chiambaretta, organizers Marc Sanchez and Jérôme Sans, Paris, France

- Museum if Fine Arts of Chartres, Primitive Body Digital Body, Chartres, France

- Stephan Stux Gallery, Orlan, Digital Photographs and Sculptures, Refiguration / Self-Hybridization : The Pre-Columbian and African Series, New York, USA

- Artcurial, Face-to-face, organizer Isabelle de Montfumat, Paris, France

- Kunsthalle & Kunstforum Wien, Superstars, organizer Thomas Miessgang, Vienna, Austria

- Mildred Kemper Art Museum, Inside Out Loud : Visualizing Women’s Health, organizer Janine Mileaf, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

- Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Lausanne, Body Extensions, Lausanne, Switzerland

- Museum of Fine Arts of Buenos Aires, Projet Cone Sud, organizers Bernard Goy and Gusto Pastor Mellado, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- National Gallery of Victoria, Mirror Mirror : Reflections on Beauty, Melbourne, Australia

- 2004

- Centre de Création Contemporaine (CCC), Orlan, 1993, organizer Alain Julien-Laferrière, Tours, France

- Centre National de la Photographie (CNP), Orlan 1964–2004... Méthodes de l’artiste, retrospective exhibition, organizers Régis Durand and Claire Guézengar, with a monograph published by Flammarion, Paris, France

- Moscow House of Photography, Orlan, 2003–2004, organizer Olga Svlibova, retrospective exhibition conjointly held with the Photobiennale 2004, Moscow, Russia

- UNESCO, In Movement UNESCO Salutes Women Video Artists of the World, organizer Kim Airyung, Paris, France

- ZKM, Media Art Net, organizer Peter Weibel, Karlsruhe, Allemagne

- 2003

- AFAA, Le Plan du film, Paris, France

- FRAC des Pays de la Loire, Éléments favoris, retrospective, organizer Jean-François Taddei, Carquefou, Nantes, France

- Michel Rein Gallery, Tricéphale, photographies et installation vidéo, Paris, France.

- Galerie der HGB, Academy of Visual Arts, Bellissima, Leipzig, Germany

- Galleria d’Arte Moderna, La Creazione ansiosa, da Picasso a Bacon, Verona, Italy

- Hungarian Photography House, La Fabrication du réel, Budapest, Hungary

- Musée de l'Élysée, Face, Lausanne, Switzerland

- Museum of Fine Arts of Québec, Doublures, Quebec, Canada.

- 2002

- Centro de Fotografía of the Université of Salamanca, Retrospective 1964-2001, organizer Olga Guinot, Palace Abrantès and the church of Segonda Palace, Salamanca, Spain

- FRAC des Pays de la Loire, Éléments favoris, retrospective, organizer Jean-François Taddei, Carquefou, Nantes, France

- Centro-Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporáneo (Artium), Orlan 1964–2001, organizer Juan Guardiola, Vitoria, Espagne

- Hall Central of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

- The Jewish Community Center in Manhattan, Dangerous Beauty, New York, USA

- Kunsthalle Wien, Living Pictures, Vienna, Austria

- 2001

- Fondation Cartier, Le Plan du film, séquence 2, Soirées Nomades, Paris, France

- Sejul Gallery, Orlan, Self-hybridations pre-colombians, Seoul, Korea

- Museum voor Modern Art, Between Earth and Heaven, New Classical Movements in Art Today, organizer W. Van den Bussche, Ostende, Belgium

- The Rencontres d’Arles Photography Festival, Abbey of Montmajour, organizer Alain Sayag, Arles, France

- Borusan Foundation, Les Voluptés, organizer Elga Wimmer, Istanbul, Turkey

- Festival E-Phos 2001, The Hybrid Body and the Monster, Athens, Greece

- Musée d’Art Contemporain d’Anvers, Mutilate Mode and Body Art 2001: Landed/Geland, Anvers, Belgium

- 2000

- Gallery of the School of Fine Arts of Marseille, Orlan, triomphe du baroque, organizer Michel Enrici, Marseille, France

- Australian Museum, Body Art – adorned and transformed exhibition, Sydney, Australia

- Contemporary Art Center of Auvers-sur-Oise, L’Invention des femmes, organizer Marie-Hélène Dumas, Auvers-sur-Oise, France

- Centre Georges Pompidou, La Grâce (with Michel Maffesoli), Revue Parlée, Paris, France

- Deste Foundation, organizer Daniel Abadie, Athens, Greece

Bibliography

- 2011

- Camille Morineau, Blandine Chavanne, Christine Buci-Glucksmann, "Un bœuf sur la langue Orlan", Lyon, Éditions Fage, 2011.

- Orlan, "Ceci est mon corps... ceci est mon logiciel", postface by Maria Bonnafous-Boucher, Ed Al Dante Aka, Collection Cahiers du Midi — Collection de l'Académie royale des beaux-arts de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, 2011

- 2010

- Homi K. Bhabha, Rhonda K. Garelick, Michel Serres, Isabel Tejeda, Jorge Daniel Veneciano, Paul Virilio, and Lan Vu, "Faboulous Harlequin, Orlan and the patchwork self", edited by the University of Nebraska, 2010 (Received the First Price "Museum Publication Design" from the American Association Museums for 2011)

- Bouchard Gianna, Buci-Glucksmann Christine, Caygill Howard, Donger Simon, Gilman Sander L., Hallensleben Markus, Hauser Jens, Johnson Dominic, Malysse Stéphane, Olbrist Hans Ulrich, Orlan, Petitgas Catherine, Shepherd Simon, Virilio Paul, Wilson Sarah, "Orlan, A Hybrid Body of Artworks", ed. Routledge, London, UK, to be published in 2010

- Enthoven Raphael, Orlan, Vaneigem Raoul, "Unions Libres, Mariages Mixtes et Noces Barbares", Editions Dilecta, Paris, France

- 2009

- Orlan, Virilio Paul, "Transgression, transfiguration [conversation]", ed. L’Une et L’Autre, Paris, France, 2009

- 2008

- Cruz Sanchez Pedro Alberto, De la Villa Rocio, Garelick Rhonda, Serres Michel, Tejeda Isabel, Vu Lan, "Orlan + davidelfin. SUTURE-HYBRIDISATION-RECYCLING", catalogue of the exhibition held at Espacio Artes Visuales, Editions E.A.V., Murcia, Spain, 2008

- 2007

- Bader Joerg, Hegyi Lóránd, Kuspit Donald, Iacub Marcela, Phelan Peggy, Viola Eugenio, "Orlan, The Narrative", Editions Charta, Milan, Italy, 2007

- Barjou Nathalie, Deflandre Laurent, Dubrulle Antonia, Gautheron Marie, Laot Clémence, Marquis Charlène, Noesser Cécile, Normand Olivier, "Orlan, Morceaux choisis", ed. Ecole Nationale Supérieure/Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Étienne Métropole, Lyon, France, 2007

- Orlan, "Pomme-cul et petites fleurs", Editions Baudoin Jannink, Paris, France, 2007

- 2005

- O’Bryan Jill, "Carnal Art. Orlan’s Refacing", University of Minnesota Press, USA, 2005

- 2004

- Blistène Bernard, Buci-Glucksmann Christine, Cros Caroline, Durand Régis, Heartney Eleanor, Le Bon Laurent, Obrist Hans Ulrich, Orlan, Rehberg Vivian, Zugazagoitia Julian, "Orlan (English language version: Orlan, Carnal Art)", ed. Flammarion, Paris, France, 2004

- 2002

- Blistène Bernard, Buci-Glucksmann Christine, Guardiola Juan, Guinot Olga, Orlan, Ramirez Juan Antonio, Zugazagoitia Julian, "Orlan 1964-2001, catalogue of the retrospective at the Centro de Fotografía of the University of Salamanca", Ediciones Artium, Salamanca, Spain, 2002

- 2001

- Baqué Dominique, Bartelik Marek, Orlan, "Orlan, Refiguration, Self-hybridations. Pre- Columbian Series", Editions Al Dante, Paris, France, 2001

- Baqué Dominique, Yun Jin-Sup, "Orlan, Refiguration Self-hybridations", catalogue of the exhibition held at Sejul Gallery, Korea, 2001

- Quadruppani Serge, Rehm Jean-Pierre, "Le Plan du Film. Séquence 1, book accompanying the CD of the band Tanger", ed. Laurent Cauwet/Al Dante, Romainville, France, 2001

- 2000

- Buci-Glucksmann Christine, Enrici Michel, "Orlan, Triomphe du Baroque", Editions Images En Manœuvres, Marseille, France, 2000 (Cover Photo of Orlan)

- Ince Kate, Orlan, "Millennial Female", ed. Berg Publishers, Oxford, UK, 2000

- Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Délégation aux Arts Plastiques (editor), "Orlan, From the Artist’s Kiss to Carnal Art". Multimedia Monograph, Editions Jeriko, Paris, France, 2000

- 1999

- Bourgeade Pierre, Orlan, "Orlan, Self-hybridations", Editions Al Dante, Romainville, France, 1999

- 1998

- Bastille Marie-Josée, Gattinoni Christian, Lafargue Bernard, Orlan, Pearl Lydie, Rieusset-Lemarié Isabelle, Savary Joël, "Une oeuvre d’Orlan", Editions Muntaner, Collection Iconotexte, Marseille, France, 1998

- Becce Sonia, François Serge, Jacoby Roberto, "Orlan. Omniprésence", Editions Galerie d’art L’Alliance, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1998

- 1997

- Alfano Miglietti Francesca, Caronia Antonio, Francalanci Ernesto L., Ribettes Jean-Michel, catalogue of the exhibition "Orlan", Lattuada Studio, Milan, Italy, 1997

- Orlan, Place Stéphane, "Orlan, de L’Art charnel au Baiser de l’artiste", Editions Jean-Michel Place & Fils, collection Sujet-Objet, Paris, France, 1997

- 1996

- Adams Parveen, François Serge, Onfray Michel, Stone Rosanne Allucquère, Wilson Sarah, "Orlan: Ceci est mon corps, ceci est mon logiciel", Black Dog Publishing limited, London, UK, 1996

- Alfano Miglietti Francesca, "Orlan", Virus Production, Milan, Italy, 1996 Bonito Oliva Achille, Ceysson Bernard, Di Marino Bruno, Fagone Vittorio, Karttunen Ulla,

- Perniola Mario, "Orlan 1964-1996", Editions Diagonale, Rome, Italy, 1996

- 1994

- Donguy Jacques, Fabre Gladys, Gilbert-Laporte Dominique, "Skaï and Sky, Vidéo", Editions Tierces, Paris, France, 1994

Raffier Joël, "L’Art Ushuaïa, L’extrême ORLA", Gervais Lescure ou l’art somatique", Edition ACI, Auroville, India, 1994

- 1990

- Ceysson Bernard, Savary Joël, "Orlan, l’ultime chef-d’œuvre. Les 20 ans de pub et de cinéma de sainte Orlan", exhibition catalogue, ed. Centre d’Art contemporain de Basse-Normandie, Hérouville Saint-Clair, France, 1990

- 1986

- Fabre Gladys, Mignot Dorine, "Orlan. Art Access online revue", Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986

- 1984

- Donguy Jacques, Fabre Gladys, Gilbert-Laporte Dominique, "Skaï and Sky, Vidéo", catalogue of the exhibition at Galerie J. & J. Donguy, ed. Tierces, Paris, France

References

- ↑ O'Bryan, C. Jill (2005). Carnal Art: Orlan's Refacing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-4323-3. Retrieved 26 June 2012. "She was born Mireille Suzanne Francette Porte in Saint-Étienne, France, on May 30, 1947."

- ↑ Lemma, Alessandra (2010). Under the Skin: A Psychoanalytic Study of Body Modification. London: Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-415-48569-2. Retrieved 26 June 2012. "Formerly Mireille Porte (before she changed her name), Orlan is a Professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Dijon. She is a multimedia artist using video, performance, digital images and sculpture."

- ↑ Featherstone, Mike (2000). Body Modification. London: SAGE. p. 203n12. ISBN 978-0-7619-6796-5. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ O'Bryan, C. Jill (2005). Carnal Art: Orlan's Refacing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-4323-3. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Featherstone, Mike (2000). Body Modification. London: SAGE. p. 203n12. ISBN 978-0-7619-6796-5. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Rose, Barbara. Is it art? Orlan and the transgressive act. Art in America, February 1993.

- ↑ O'Bryan, C. Jill (2005). Carnal Art: Orlan's Refacing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-4323-3. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Religion and ritual drives scholarly pursuits for 2006-2007 academic year at the Getty Research Institute. September 12, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ↑ from the 'Manifesto of Carnal Art' by Orlan (taken from the artist's website) - "Carnal Art is self-portraiture in the classical sense, but realised through the possibility of technology. It swings between defiguration and refiguration. Its inscription in the flesh is a function of our age. The body has become a “modified ready-made”, no longer seen as the ideal it once represented ;the body is not anymore this ideal ready-made it was satisfaying to sign."

- ↑ Viola, Eugenio (2007). Orlan, Le Récit (edited by E. Viola) - J.Bader, D.Kuspit, L.Hegyi, M.Jacub, P.Phelan, Orlan, E. Viola. Milano: Charta. ISBN 978-88-8158-652-3.

- ↑ Video about MesuRage at M HKA (Antwerp) in 2012

- ↑ Ince, Kate (2000). Orlan : millennial female. Oxford [u.a.]: Berg. ISBN 978-1-85973-334-9.

- ↑ O'Bryan, C. Jill (2005). Carnal Art: Orlan's Refacing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-4323-3. Retrieved 26 June 2012. "She baptized herself Sainte-Orlan in 1971."

- ↑ Orlan 'Manifesto of Carnal Art/L'Art Charnel and Refiguration/Self-Hybridation series and other works' vol.12 July 2003 n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal pp.44-48

- ↑ et.al., translated from the French by Deke Dusinberre ; [essays by Bernard Blistene, Christine Buci-Glucksmann, Regis Durand ... (2004). Orlan : [carnal art] (English lang. ed.). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080304315.

- ↑ Ferrando, Francesca (2016). "A feminist genealogy of posthuman aesthetics in the visual arts". Palgrave Communications (2): 7. Retrieved 6 July 2016. "ORLAN’s work symbolically marks the passage between the seventies and the cyberfeminist nineties, fully embracing the possibilities opened by advanced technologies."

- ↑ Jeffreys, Sheila (2005). Beauty and misogyny : harmful cultural practices in the west (Reprinted. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415351836.

- ↑ Mitrofanov, Oleg (2010). "Devotion – Orlan (Paris) – Artist". Acne Paper (9): 34.

External links

- Orlan Official Website

- Retrospective Exhibition from 05/25/07 to 09/16/07 at the Musée d'art moderne de Saint-Etienne

- Pompidou Centre, exhibition: elles@centrepompidou 2010.

- Video: interview with ORLAN, registration of a MesuRage, and short overview of her work at M HKA, Antwerp