O Armatolos

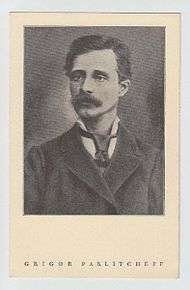

"O Armatolos" is an award-winning poem written by the 19th-century poet Grigor Parlichev. The poem was composed in 1860, and officially published on March 25 of that year to participate in the Athens University competition for best Greek language poetry, winning first place. Parlichev considered the poem his lifetime achievement, after winning the competition he was crowned with a laurel wreath, and offered scholarship to universities at Oxford and Berlin. Around 1870 Parlichev made an effort to translate the poem from the original Greek to a mixture of vernacular Eastern South Slavic and Church Slavonic, which he referred to as the Bulgarian literary language.

Basically, "O Armatolos" tells the story about the death of a legendary hero who protected the villagers from the brutal gangs of Gheg Albanians (Ghegis). The action in the poem takes place in the middle of the 19th century in the western regions of Macedonia, respectively the region between Galichnik, Reka, and the village Stan (all in present-day Republic of Macedonia). Based on the motif of the folk songs about Kuzman Kapidan, the theme of the poem develops into nine parts. The first part, based on nine quatrains, tells about the statements of the tragic struggle and death of the hero Cosmas. In the second part, Cosmas' mother distressed expects her son's return from battle, not knowing that he died. The third part is the most striking piece in the poem, telling the cry that the enemies of the peasants caused by bringing the inanimate body of Cosmas into the village. It is in this part that the poem's most popular line "screams can be heard from Galichnik in Reka" is used, as an allusion to the sorrow of the people. In the fourth part, the author returns to the scenes of Cosmas' last battle and his demise. Through the fifth part, the attackers pay due respect to Cosmas by pledging not to attack his home village. Cosmas' mother removes the curse she had said towards the village enemies and forgives them, requiring the Gheg Albanians not to attack the Reka people any more. In the sixth part is seen the grieving of Cosmas' mother and through it is told the genealogical tree of the hero. This section notes Cosmas' lover Cveta, that washes the hero with her tears. The seventh part tells how the hero's mother orders the villagers to bury Cosmas and the other fighters together with all honors. The scene of the eight part takes place at the home of Cosmas' fiancee. Folk customs would refrain her from wailing over the death of Cosmas before her father. But as soon as she was left alone, her bitter cry echoed, forcing her to give up all thing earthly and become a nun. The ninth part marks the end of the piece, in which is marked the everlasting glory of Cosmas in the village.

"O Armatolos" was very well received by 19th century Greek critics. It was described as full of high artistic quality, complex epithets, great descriptions of weapons, fine general epic narrative, characters, and a symbiosis of Homeric style and the artistic folklore-themed flair of Parlichev. Grigor Parlichev received the epithet "second Homer" from the academics of the Athens University. Today, the literally work is considered one of the finest in the creation of the Bulgarian literature and regarded in the Republic of Macedonia as the seminal work in the modern national awakening of Macedonians. However, Parlichev did get criticized by his fellow Bulgarian writers such as Kuzman Shapkarev and Dimitar Miladinov for using the Greek language rather than Slavic.

Background

Before he wrote the poem, Grigor Parlichev was moving around the Balkan Peninsula working as a teacher.[1] First he went to work in Tirana, Albania, here he would become a great fan of Homer and Greek poetry. In 1849 he visited Athens where he entered a Medical School to study medicine. In 1850, before returning to his hometown Ohrid, he visited the poetry competition in the Athens University being deeply impressed by the ceremony in which the winner is awarded by the king Otto of Greece.[2]

Parlichev always had a great respect towards the Greek culture, history, and literature, and in the time before and during the writing of the poem he was a passionate philhellene, identifying as Greek rather than Slavic Bulgarian, as he did before and after this period of his life.[3] Not only because of the great impression that the Kingdom of Greece left on him he decided to write in Greek, but also because of the Homeric style that he chose to compose his poem.[4]

In 1859 he returns to Ottoman Macedonia to work as a teacher, so he can collect enough money to continue his university studies.[5] After returning to Greece he started his second year in medicine. In this period he lacks of interest in his studies and starts work on his first poem "O Armatolos" (Greek: Ο Αρματωλός).[6] Parlichev remembers the old folk song that he was told in the village of Belica of the mythical folk hero known as Kuzman Kapidan that defeated the Albanian robbers and provided a relatively peaceful life of the village population.[7] Parlichev decided to build the poem's plot on this folk songs from western Macedonia. The period during the writing of the poem, and the study in Athens is known as the "Athenian period" of Parlichev's life, as defined by the author Raymond Detrez.[8]

Poem

The poem's story focuses on the myth of a popular or national hero, who with his activity protects people from the atrocities of the foreign enemies. The main theme of "O Armatolos" is the analyzation of the religious hatred and clashes during that period in history.[9] The original text of the poem consists of 912 verses that rhyme in the style that each second verse rhymes with the upper one. The beginning of the original version follows:

- "Screams can be heard from Galichnik to Reka.

- What a great misfortune that brought

- Together all men and women,

- All to grieve in cry?

- Did storm hit the wheat fields?

- Or a swarm of locusts swarmed?

- Did the Sultan send tax collectors

- to collect taxes prematurely and tough?"

Here the author creates an allusion of the deep sorrow of the people from Reka, still without knowing what is the cause. Asking multiple questions, suspecting situations that might strike such grieve.[10] The questions are rejected in the third stanza, giving the real cause in the fourth:

- "Neither a storm exterminated the wheat fields,

- Neither a swarm of locusts swarmed,

- Neither the Sultan sent tax collectors

- To collect early taxes, without regret.

- Cosmas, our hero, fell killed by the Gheg

- The profound armatoloi dropped in battle

- And will now dishonor the thieves on the mountains

- And to defend them, no one."

Since the beginning of the first verse, Parlichev lyrical and suggestive style by the unforced hyperbole, antithesis and Homeric comparisons, introduces the reader to the event, heralding the doom that the people of Reka have after the falling death of the armatoloi. Revealing that the source of their sorrow is his death, and that he'll be forever among them cursing the enemy that had killed him.[10] The first and second verse of the second song goes:

- "On a spring night brooding lies a

- Women sitting on the doorstep

- With her hands on her knees, and the icy flashed gun

- That she gently caresses.

- She is of median age, and cores, and quite healthy,

- Robust, strong, and heroic.

- Her body is sculpted in an Amazon attitude:

- A really sweet person."

With this words, Parlichev, describes the mother of Cosmas, and her appearance. As she is more that eagerly awaiting her sons return from battle. During the entire second song the author describes the waiting of Cosmas' mother Neda and the message that she receives of her sons decease.[11] In the third part of the poem it is seen how the enemy rebels bring the body of Cosmas into his home village through these words:

- "But suddenly they heard someone entering,

- With such a low sound:

- Four saddened Ghegs with their hats down,

- Moving through the village highway.

- Sweating, they bear the dead body, and through the porch

- Brought the priceless load,

- As people gathered silently around the body

- Giving it a dull look."

In this scene, the Ghegs bring back the inanimate body of Cosmas in the village. The narrator using epic subjectivity paints a better picture of the Ghegs. Aldo they are the blood enemies of Cosmas, from whose hand many of his comrades lost their head, they are like pilgrims of courage and honesty, on their hands they cary the dead body of Cosmas to his mother, paying their deep respect on the way.[10] In particular piety the old Gheg talks about the heroism of Cosmas, therefore swears before the dead body of the hero, that no one will offend his mother:[12]

- "And all day, you cry, you have a reason. Be strong!

- You lost, oh dear mother, a giant!

- People will sing on their knees with a wide open mouth

- For the acts of your son.

- Yes, servants of Ares, mother,

- What he did on daring feat,

- And all singers will celebrate worldwide

- With a fervor so scorching."

Parlichev, carries on describing the character of Maria, Cosmas' fiancee. Basing on folk customs she is restricted from showing her sorrow on Cosmas' death in public. And, by facing tradition her father decides to marry her to another man. Being forced beyond her will, she runs out and becomes a nun.[13]

- "Who are you woman,

- That stands cold crying in the hot?

- A nun, she is, Fitiou,

- Whose steel heart's beating in her chest."

The poem ends with the verses:

- "Near Galichnik, a small sacred hill

- Willows planted all.

- And rustles river fast like a snake, flowing,

- Crystal waters lining.

- Sunlight barely comes there,

- In shady branches here,

- As spring neared, birds came,

- Sadly comes, with a cry.

- The tired traveler thoughtfully sits here

- Leaning under a willow.

- Listening to the reaching bird songs,

- The entire spring melody —

- Playing harps, sitting by the road,

- He sings to the beggar,

- And I, a mere taker, will pass here once,

- Writing it line by line."

Artistically, the author leaves the readers with a slight picture of the region around Galichnik, where the poem takes place. With a willow planted landscape, the birds coming in spring, the beautiful sounds that succeed the cold, the bad, when everyone could calm down and rest.[14]

Contest

"O Armatolos" was published on March 25, 1860 for Parlichev's sole purpose of entering it in the Greek royal poetry competition of the Athens University.[15] However, the poem was officially adopted in February the same year by the contest committee of the university.[15] The poem was announced as winner of the competition by the prominent Greek poet Alexandros Rhizos Rhangaves. In his autobiography Parlichev states:

| “ | I felt an indescribable woolen such as I had never felt ... Excessive joy is more devastating than deep sorrow... | ” | |

| — Parlichev, [15] | |||

Three days after the poem received the prize in the anonymous competition, Parlichev was called by the university authorities to recite the poem in order to proof he is the author.[15] The laurel wreath as the central prize was presented to him by the Greek king Otto.[16] Together with the first prize he would if received a cash prize, and a scholarship to several European universities, including Oxford. However soon after a scandal with his non-Greek origin sparked the public opinion in Greece, which led to a vitiation of the competition.[17] Frustrated Parlichev returned to his native town of Ohrid and in 1862 became an activist of the movement for the Bulgarian National Revival.[18]

| “ | creation of miraculous chisel ... every verse sparkles like pure pearl | ” | |

| — Alexandros Rhizos Rhangaves, [19] | |||

In 1870 he would translate a part of the poem into a variety language, completed by him, which he called Bulgarian literary language.[20]

Published translations

| Year | Bulgarian language | Macedonian language |

|---|---|---|

| 1895 | G. Balastchev, G. Parlichev: Serdaryat, Sofia ♦[21] | |

| 1930 | V. Pundev, G. Parlichev: Serdaryat (Literary Work), Sofia ♦[22] | |

| 1944 | G. Kiselinov, G. Parlichev: Serdarot, "Makedonija", Skopje †[23] | |

| 1946 | K. Toshev, G.S. Parlichev: Serdarot, State Publishing Company of Macedonia, Skopje †[24] | |

| 1952 | K. Kjamilov, Serdarot, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje ‡[22] | |

| 1953 | G. Stalev, G.S. Parlichev: Autobiography. Serdarot, "Kocho Racin", Skopje •[25] | |

| 1959 | G. Stalev, Selected Pages - Serdarot, "Kocho Racin", Skopje •[22] | |

| 1968 | M. Arnaudov, G. Parlichev - Serdaryat, "Otechestvenii︠a︡ front", Sofia ♦[26] | G. Stalev, Serdarot - Autobiography, "Misla", Skopje •[27] |

| 1970 | A. Germanov, G. Parlichev: Voivoda, "Balgarski Pisatel", Sofia ♦[28] | |

| ♦ - indicates a Bulgarian language translation from the original Greek. † - indicates a Macedonian language translation based on the Bulgarian one. ‡ - indicates publishing of the original translation by Parlichev in Church Slavonic. • - indicates a Macedonian language translation from the original Greek. | ||

| Source: XXXVII International Scientific Conference Seminar on Literature, Culture, and Language in Macedonia | ||

References

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p.39

- ↑ Parlichev, p.23 (depending on issue)

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p. 41

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p. 40

- ↑ "Grigor Prlichev - the "second homer"". Makedonska Nacija. October 6, 2012.

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p.48

- ↑ Kramarich, p.238

- ↑ Raymond Detrez (2007), "Canonization through Competition: The Case of Grigor Părličev", Literary Thought (in Bulgarian), pp. 1–41

- ↑ G. Parlichev (1993). Serdarot (foreword). Ljubljana: Makedonsko kulturno društvo »Makedonija«. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Grigor S. PRLIČEV; Todor I. DIMITROVSKI; Dimitar Mitrev; Georgi Stalev (1958). Автобиографија. Сердарот. Предговор на Димитар Митрев. (Автовиографија: Превод, објасненија, речник од Тодор Димитровски. Сердарот: Препев од Горѓи Сталев. Skopje: Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. pp. 1–128.

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p. 120

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p. 121

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p. 123

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), p. 236

- 1 2 3 4 Parlichev's autobiography

- ↑ Ioannis N. Grigoriadis (2012). Instilling Religion in Greek and Turkish Nationalism: A "Sacred Synthesis". Palgrave Macmillan. p. 113.

- ↑ Peter Mackridge, Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766-1976, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 019959905X, p. 189.

- ↑ Ioannis N. Grigoriadis, Religion in Greek and Turkish Nationalism: A “Sacred Synthesis”, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, ISBN 1137301198, p. 22.

- ↑ Pandeva (2010), P. 11

- ↑ Криволици на мисълта. Раймон Детрез, превод: Жерминал Чивиков. София: ЛИК, 2001, ISBN 954-607-454-3, стр. 147.

- ↑ Khristo Angelov Khristov (1999). Ent͡siklopedii͡a Pirinski kraĭ: v dva toma, Volume 2; Volume 5. Sofia: Red. "Ent͡siklopedii͡a". p. 170.

- 1 2 3 Pandeva (2010), p. 55

- ↑ "УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ "Св. КИРИЛ И МЕТОДИЈ" – СКОПЈЕ Меѓународен семинар за македонски јазик, литература и култура:". Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje. Scribd.com. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Blaže Koneski (1988). Zbornik vo čest na Krum Tošev: naučen sobir po povod 10 godini od smrtta na profesor Krum Tošev. Faculty of Philology, Skopje. Katedra za makedonski jazik i južnoslovenski jazici. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Мирољуб Стојановић. МАКЕДОНСКА КЊИЖЕВНОСТ. Niš, Serbia: University of Niš.

- ↑ Mikhail Arnaudov (1968). Grigor Pŭrlichev. Nat︠s︡ionalnii︠a︡ sŭvet na Otechestvenii︠a︡ front.

- ↑ Gligor Parlichev; work by Georgi Stalev (1968). Serdarot. Avtobiografija. Misla, Skopje. OCLC 24644375. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Raymond Detrez. ""Албанската връзка" на Григор Пърличев" (in Bulgarian and English). Ghent University. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

Further reading

- Liljana Pandeva (2010), XXXVII International Scientific Conference Seminar on Literature, Culture, and Language in Macedonia (PDF), Skopje: Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje, pp. 1–304, ISBN 978-9989-43-305-4, retrieved September 1, 2013

- Grigor Parlichev (2003; multiple editions), "Serdarot: Autobiography", Balgarski pisatel, Matica makedonska, pp. 1–130, ISBN 9789989484650 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Kramarić, Zlatko (1991), Makedonske teme i dileme, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, OCLC 608354600

- Dorothea Kadach (1971), Zwei griеchische Gedichte von Grigor S. Prličev, Berlin: Ellenika 24

- Raymond Detrez (1992), Grigor Părličev : een case-study in Balkannationalism (in Dutch), Antwerpen : Restant, OCLC 32204435, OL 19031060M