Ogyrididae

| Ogyrididae | |

|---|---|

| |

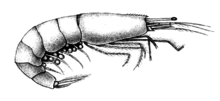

| Ogyrides alphaerostris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Infraorder: | Caridea |

| Superfamily: | Alpheoidea |

| Family: | Ogyrididae Holthuis, 1955 |

| Genera | |

|

Ogyrides Stebbing, 1914 | |

Ogyrididae is a family of decopod crustaceans consisting of 10 species.[1]

Appearance

Eyes are elongate, reaching nearly to distal end of antennular peduncle. Their first pair of pereiopods is robust and similar in size to the second pair; distinctly chelate. The second pair of pereiopods is divided into four articles. The first maxilliped has an exopod far removed from the endite. But the second maxilliped has segments arranged in usual serial manner; bearing exopod; endopod 4-segmented. Mandible usually with incisor and molar processes and palp. Second maxilla with palp; endite well developed.[2]

Diet

During early years the majority of their diet is composed of sea plankton, sea plants and sea weed. A grown long-eyed shrimp would eat small worms and microscopic organisms. From time to time the might cosume dead fish or crabs and occacionally they would turn and eat their own.[3]

Habitat

This genus contains 10 species distributed along tropical and subtropical coasts around the world. Most of the species in this genome have been found of Australia and Mexico coasts. In this areas the shrimps have the optimal conditions and temperature to survive.[4]

Behaviour

Long-eyedsalked shrimps exhibit complex behaviors like eusociality. Newly molted individuals have displayed a shift of their entire body forwards, with the cephalothorax angled downwards with respect to the pleon and both chelipeds extended forwards and towards each other; body jerked rapidly backwards with pleon curled and walking pereiopods extended; cephalothorax angled upwards, while the chelipeds were spread apart and moved backwards; and continuous undulations of pleopods. Is important to note that this only happened in individuals that were in their burrowes and in the presence of light.[5]

References

- ↑ Grave S. De, Pentcheff N. D., Ahyong S. T., Chan T. Y., Crandall K. A., Dworschak P. C., Felder D. L., Feldmann R. M., Fransen C. H. J. M., Goulding L. Y. D., Lemaitre R., Low M. E. Y., Martin J. W., Ng P. K. L., Schweitzer C. E., Tan S. H., Tshudy D., Wetzer R. (2009). "A classification of living and fossil genera of decapod crustaceans" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 21 (suppl.): 1–—109.

- ↑ Williams, A. B. (1972). "A Ten-Year Study of Meroplankton in North Carolina Estuaries: Mysid Shrimps". Chesapeake Science. 13 (4): 254. doi:10.2307/1351109. JSTOR 1351109.

- ↑ "What Do Shrimps Eat?". diet.yukozimo.com. Retrieved 2014-12-16.

- ↑ M, Ayón-Parente; J, Salgado-Barragán. "A new species of the caridean shrimp genus Ogyrides Stebbing, 1914 ... - PubMed - NCBI". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2014-12-16.

- ↑ Zeng,Yiwen. "REPETITIVE-MOTION DISPLAY: A NEW BEHAVIOUR IN A BURROWING ALPHEID SHRIMP". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2014-12-16.