Operation Manta

| Operation Manta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chadian-Libyan conflict | |||||||

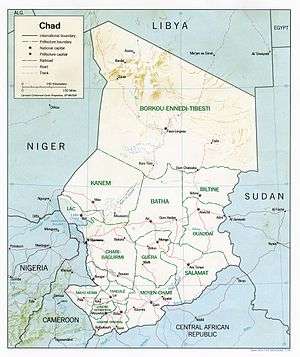

GUNT-controlled area in Chad until 1986/87 (light-green), "red line" on 15th and 16th latitude (1983 and 1984) and Libyan-occupied Aouzou-strip (dark-green) | |||||||

| |||||||

Operation Manta is the code name for the French military intervention in Chad between 1983 and 1984, during the Chadian-Libyan conflict. The operation was prompted by the invasion of Chad by a joint force of Libyan units and Chadian Transitional Government of National Unity (GUNT) rebels in June 1983. While France was at first reluctant to participate, the Libyan air-bombing of the strategic oasis of Faya-Largeau starting on July 31 led to the assembling in Chad of 3,500 French troops, the biggest French intervention since the end of the colonial era.

The French troops, instead of attempting to expel the Libyan forces from Chad, drew a "line in the sand".[1] They concentrated their forces on the 15th parallel, the so-called "Red Line," (later moved up to the 16th parallel) to block the Libyan and GUNT advance towards the N'Djamena, thus saving the Chadian President Hissène Habré. The Libyan and rebel forces also avoided attacking across the Red Line and provoking the French. The resulting impasse led to the de facto partition of Chad, with the Libyans and the GUNT in the north and Habré and the French in central and southern Chad.

To end this stalemate, French President François Mitterrand and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi negotiated a mutual withdrawal of their countries' troops from Chad in September 1984. The accord was respected by the French, thus signing the end of Operation Manta, but not by the Libyans, whose forces remained in Chad until 1987 (they did, however, continue to respect the Red Line). The violation of the 15th parallel caused a renewed French intervention in Chad under Operation Epervier and the expulsion of Libyan forces from all Chad except for the Aouzou Strip the following year.

Background

Chad had been involved in a civil war since 1965, which reached its most dramatic phase in 1979 when a fragile alliance between the President Félix Malloum and the Prime Minister Hissène Habré collapsed, unleashing factional politics. International mediators midwifed the formation of a Transitional Government of National Unity (GUNT), comprising all armed factions, but civil war reignited in 1980 when Habré, now Defence Minister, rebelled against the GUNT's Chairman, Goukouni Oueddei. Habré succeeded in taking N'Djamena, the Chadian capital, on August 7, 1982.[2] Refusing to acknowledge Habré as the new Chadian President, Goukouni refounded the GUNT as an anti-Habré coalition of armed groups in October in the town of Bardaï .[3]

While Gaddafi had kept himself mostly aloof in the months prior to the fall of N'Djamena,[4] he decided to reinvolve himself in the Chadian conflict after Goukouni's fall. He recognized Goukouni as the legitimate ruler of Chad and decided to arm and train his forces.[5]

Crisis

Gaddafi, judging the time to be ripe for a decisive offensive, ordered a massive joint GUNT-Libyan attack against Faya-Largeau, the main government stronghold in northern Chad, during June 1983. The fall of the city on June 24 generated a crisis in Franco-Libyan relations, with the French Foreign Minister Claude Cheysson announcing that day that France "would not remain indifferent" to Libya's intervention in Chad.[6]

The 3,000 man-strong GUNT force continued its advance towards Koro Toro, Oum Chalouba and Abéché, the main city in eastern Chad, which fell on July 8. These victories gave Goukouni and Gaddafi control of the main routes from the north to N'Djamena,[3][7] and also severing Habré's supply line to Sudan.[2]

As the rebels advanced, with poorly concealed assistance from Libya, Habré appealed for international help. Rejecting direct intervention and downplaying the Libyan role, France was prepared to go no further than airlifting arms and fuel, with the first French arms shipments arriving on June 27. On July 3, Zaire flew in a detachment of 250 paratroopers, eventually raised to about 2,000 men. Deployed chiefly around N'Djamena, the Zaireans freed Chadian troops to fight the rebels. The United States further announced that 25 million US dollars in military and food aid would be provided. Thus assisted, and taking advantage of the GUNT's overextended supply line, Habré took personal command of the Chadian National Armed Forces (FANT) and drove Goukouni's army out of Abéché four days after the city's fall. FANT recaptured Faya-Largeau on July 30 and went on to retake other points in the north.[2][3]

French intervention

Faced with the collapse of the GUNT-Libyan offensive, Gaddafi increased his force commitment forces in Chad. Libyan MiGs bombed Faya-Largeau on the day after it was recaptured by FANT, in the first undisguised Libyan intervention in the crisis.[6] A force of 11,000 Libyan troops, complete with armour and artillery, was airlifted into the Aouzou Strip, to support the GUNT forces, along with eighty combat aircraft, a considerable portion of the Libyan Air Force. Habré entrenched himself in Faya-Largeau with 5,000 troops, but he could not match the massive Libyan firepower, losing a third of his army and being forced out of Faya and retreating 200 miles south.[8]

Habré issued a fresh plea for French military assistance on August 6.[9] French President François Mitterrand, under pressure from the US and Francophone African states, announced on August 9 his determination to contain Gaddafi. A ground force was rapidly dispatched from the bordering Central African Republic, beginning Operation Manta.[10][11]

The first French contingents were deployed north of N'Djamena at points on the two possible routes of advance on the capital. Fighter aircraft and antitank helicopters were dispatched to Chad to discourage an attack on N'Djamena. As the buildup proceeded, forward positions were established roughly along the 15th parallel from Mao in the west to Abéché in the east (the so-called "Red Line"), which the French tried to maintain as the line separating the combatants. This force eventually rose to become the largest expeditionary force ever assembled by France in Africa since the Algerian War, reaching 3,500 troops and several squadrons of Jaguar fighter-bombers.[2][10][11]

Stalemate

Although France said it would not tolerate Libya's military presence at Faya-Largeau on August 25,[12] Mitterrand was unwilling to openly confront Libya and return northern Chad to Habré. This inaction gave the impression that the French were willing to concede control of Northern Chad to Gaddafi. The Libyans, too, avoided crossing the Red Line, thereby avoiding engagement with the French troops.[11]

While the division of the country left Habré unsatisfied with Gaddafi's influence in Chadian affairs, the Chadian President benefited greatly from the French intervention. He was also able to restore his old ties with the French military, and create new ones with the French Socialists. On the other side of the Red Line, the stalemate was a far greater problem for the GUNT, bogged down in the arid north but far away from Tripoli, where the main decision-making took place. It was only a question of time before rifts would start emerging between the Libyan military and the GUNT forces, due to Libya's inability to balance the demands from these two groups.[13]

France and Libya pursued bilateral negotiations independently from the Chadian factions which they sponsored, as well as the militantly anti-Libyan Reagan Administration in the United States, which favoured negotiations between Goukouni and Habré. For a time, France seemed interested in the Libyan suggestion of replacing Habré and Goukouni with a "third man." However, these negotiation attempts repeated the failure of the peace talks which had been promoted by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in November 1983.[11][12]

Renewed fighting

The OAU-supported mediation attempt made by Ethiopia's leader Mengistu Haile Mariam at the beginning of 1984 was not any more successful than previous attempts. On January 24, GUNT troops backed by heavily armed Libyan counterparts, overran the Red Line and attacked the FANT outpost of Ziguey, northern Kanem,[14][15] 200 km south of the Red Line in order to secure French and African support for new negotiations. Thirty FANT soldiers were killed and twelve taken prisoner, while in Zine, close to Mao, two Belgian doctors of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) were taken hostage.[16]

This attack forced the French to counter-attack, although not in the manner desired by Habré. He felt the French ought to retaliate by striking the GUNT at Faya-Largeau, which would have served as a declaration of war on Libya and escalated the conflict, something Mitterrand wanted to avoid at all costs. Instead, on January 25, French Defence Minister Charles Hernu ordered two Jaguar fighter-bombers to interdict the attackers and pursue them during their retreat. While the advance was blocked, a Jaguar was shot down and its pilot killed, leading to the January 27 decision to move the Red Line from the 15th to the 16th parallel, running from Koro Toro to Oum Chalouba. The French also moved a squadron of four Jaguars from Libreville, Gabon to N'Djamena.[11][17][18]

French withdrawal

On April 30, Gaddafi proposed a mutual withdrawal of both French and Libyan forces from Chad in order to end the stalemate. The offer was accepted by Mitterrand, and four months later, Mitterrand and Gaddafi met on September 17, announcing that the troop withdrawal would start on September 25, and be completed by November 10.[12] The Libyan offer arrived when the French were becoming bogged down in an intervention that promised no rapid solution. Also, the cost of the mission, which had reached a 150 million CFA Francs per day, and the loss of a dozen troops following a number of incidents, turned the majority of French public opinion in favour of the departure of French forces from Chad.[19]

The agreement was initially hailed in France as a great success that attested to Mitterrand's diplomatic skills. The French troops retired before the expiry of the agreed withdrawal date, leaving behind only a 100-strong technical mission and a considerable amount of material for the FANT. To Mitterrand's embarrassment, France discovered on December 5 that Gaddafi, while pulling out some forces, had kept at least 3,000 troops camouflaged in the north.[12][20][21]

Reactions to the withdrawal

The French withdrawal badly strained Franco-Chadian relations, as Habré felt both insulted and abandoned by the French government. Rumors of "secret clauses" in the Franco-Libyan accord spread from N'Djamena throughout Africa. These rumors obligated the French Foreign Minister Roland Dumas to formally deny the existence of such clauses in the Franco-African summit held in Bujumbura in December. Mitterrand resisted pressure from African governments to return to Chad, with the Foreign Relations Secretary of Mitterrand's Socialist Party Jacques Hustinger proclaiming that "France can't be forever the gendarme of Francophone Africa".[22]

After the return of the French troops in their country, Mitterrand found himself accused both at home and abroad of having been naive in trusting the word "of a man who has never maintained it". Gaddafi emerged with a major diplomatic victory that enhanced his status as a Third World leader who had duped the French government.[23]

Aftermath

The year following the French withdrawal was one of the quietest since the ascent to power of Habré, with both forces carefully remaining on their side of the Red Line, even if the GUNT had initially expressed the desire to march on N'Djamena and unseat Habré. Habré instead used the truce to strengthen his position through a series of peace accords with minor rebel groups. These weakened the GUNT, which was increasingly divided by internal dissension and progressively estranged from the Libyans, who were pursuing a strategy of annexation towards northern Chad.[24][25]

At the beginning of 1986, the GUNT was increasingly isolated internationally and disintegrating internally. In reaction to this decline of his client, which legitimized the Libyan presence in Chad, Gaddafi encouraged the rebels to attack the FANT outpost of Kouba Olanga across the Red Line on February 18, with the support of Libyan armour. This brought the French return to Chad in Operation Epervier, restoring the Red Line. A few months later and to the surprise of no one, the GUNT rebelled against its former Libyan patrons, opening the way for the Toyota War in 1987 which expelled the Libyans from all Chad except the Aouzou Strip. The Aouzou Strip was finally restored to Chad in 1994.[26]

References

- Azevedo, Mario J. (1998). Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Routledge. ISBN 90-5699-582-0.

- Brecher, Michael & Wilkenfeld, Jonathan (1997). A Study in Crisis. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10806-9.

- Collelo, Thomas (1990). Chad. US GPO. ISBN 0-16-024770-5.

- Jessup, John E. (1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945-1996. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28112-2.

- Ngansop, Guy Jeremie (1986). Tchad: Vingt d'ans de crise (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-85802-687-4.

- Nolutshungu, Sam C. (1995). Limits of Anarchy: Intervention and State Formation in Chad. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1628-3.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (2002). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3733-2.

Notes

- ↑ Smith, William E. (1983-08-29). "France Draws the Line". Time.

- 1 2 3 4 T. Collelo, Chad

- 1 2 3 S.Nolutshungu, Limits of Anarchy, p. 188

- ↑ S. Nolutshungu, p. 185

- ↑ K. Pollack, Arabs at War, p. 382

- 1 2 M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, A Study in Crisis, p. 91

- ↑ M. Azevedo, Roots of Violence, p. 110

- ↑ K. Pollack, p. 183

- ↑ J. Jessup, An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict, p. 116

- 1 2 M. Azevedo, p. 139

- 1 2 3 4 5 S. Nolutshungu, p. 189

- 1 2 3 4 M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 92

- ↑ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 189–190

- ↑ M. Azevedo, p. 110, 139

- ↑ S. Nolutshungu, p. 189, 191

- ↑ G. Ngansop, Tchad, p. 150

- ↑ M. Azevedo, p. 110

- ↑ G. Ngansop, pp. 150–151

- ↑ G. Ngansop, pp. 154–155

- ↑ S. Nolutshungu, p. 190

- ↑ M. Azevedo, pp. 139–140

- ↑ G. Ngansop, p. 158

- ↑ M. Azevedo, p. 140

- ↑ G. Ngansop, pp. 159–160

- ↑ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 191–193

- ↑ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 212–228