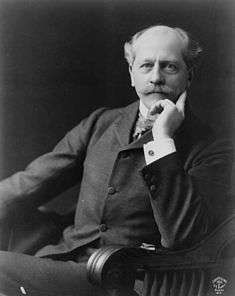

Percival Lowell

| Percival Lowell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 13, 1855 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

November 12, 1916 (aged 61) Flagstaff, Arizona, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Education | Noble and Greenough School |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Known for | Martian canals, Asteroids discovered: 793 Arizona (April 9, 1907) |

Percival Lawrence Lowell (/ˈloʊəl/; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars. He founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona and formed the beginning of the effort that led to the discovery of Pluto 14 years after his death.

Biography

Percival Lowell was a member of the wealthy Boston, Massachusetts, Lowell family. He was born in Cambridge on March 13, 1855,[1] the brother of Abbott Lawrence Lowell and Amy Lowell.[1][2]

Percival graduated from the Noble and Greenough School in 1872 and Harvard University in 1876 with distinction in mathematics.[2] At his college graduation, he gave a speech, considered very advanced for its time, on the nebular hypothesis. He was later awarded honorary degrees from Amherst College and Clark University.[3] After graduation he ran a cotton mill for six years.[1]

In the 1880s, Lowell traveled extensively in the Far East. In August 1883, he served as a foreign secretary and counsellor for a special Korean diplomatic mission to the United States. He lived there for about two months.[1] He also spent significant periods of time in Japan, writing books on Japanese religion, psychology, and behavior. His texts are filled with observations and academic discussions of various aspects of Japanese life, including language, religious practices, economics, travel in Japan, and the development of personality.

Books by Percival Lowell on the Orient include Noto: An Unexplored Corner of Japan (1891) and Occult Japan, or the Way of the Gods (1894), the latter from his third and final trip to the region. His time in Korea inspired Chosön: The Land of the Morning Calm, [1] (1886, Boston). The most popular of Lowell's books on the Orient, The Soul of the Far East (1888), contains an early synthesis of some of his ideas, that in essence, postulated that human progress is a function of the qualities of individuality and imagination. The writer Lafcadio Hearn called it a "colossal, splendid, godlike book."[4] Another of his books is The Eve of the French Revolution (1892),[5] and at his death he left with his assistant Wrexie Leonard an unpublished manuscript of a book entitled Peaks and Plateaux in the Effect on Tree Life.[4]

He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1892.[6] He moved back to the United States in 1893.[1] Beginning in the winter of 1893–94, using his wealth and influence, Lowell dedicated himself to the study of astronomy, founding the observatory which bears his name.[2] In 1904, Lowell received the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société astronomique de France, the French astronomical society. For the last 23 years of his life astronomy, Lowell Observatory, and his and others' work at his observatory were the focal points of his life.

World War I very much saddened Lowell, a dedicated pacifist. This, along with some setbacks in his astronomical work (described below), undermined his health and contributed to his death from a stroke on November 12, 1916, aged 61.[7] Lowell is buried on Mars Hill near his observatory. He was an agnostic.[8]

Astronomy career

Lowell became determined to study Mars and astronomy as a full-time career after reading Camille Flammarion's La planète Mars.[9] He was particularly interested in the canals of Mars, as drawn by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who was director of the Milan Observatory.

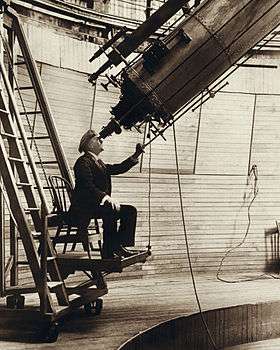

In 1894 Lowell chose Flagstaff, Arizona Territory, as the home of his new observatory. At an altitude of over 2,100 meters (6,900 feet), with few cloudy nights, and far from city lights, Flagstaff was an excellent site for astronomical observations. This marked the first time an observatory had been deliberately located in a remote, elevated place for optimal seeing.[2]

Canals of Mars

For the next fifteen years he studied Mars extensively, and made intricate drawings of the surface markings as he perceived them. Lowell published his views in three books: Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and Mars As the Abode of Life (1908). With these writings, Lowell more than anyone else popularized the long-held belief that these markings showed that Mars sustained intelligent life forms.[10][11]

His works include a detailed description of what he termed the 'non-natural features' of the planet's surface, including especially a full account of the 'canals,' single and double; the 'oases,' as he termed the dark spots at their intersections; and the varying visibility of both, depending partly on the Martian seasons. He theorized that an advanced but desperate culture had built the canals to tap Mars' polar ice caps, the last source of water on an inexorably drying planet.[12]

While this idea excited the public, the astronomical community was skeptical. Many astronomers could not see these markings, and few believed that they were as extensive as Lowell claimed. As a result, Lowell and his observatory were largely ostracized.[13] Although the consensus was that some actual features did exist which would account for these markings,[14] in 1909 the sixty-inch Mount Wilson Observatory telescope in Southern California allowed closer observation of the structures Lowell had interpreted as canals, and revealed irregular geological features, probably the result of natural erosion.[15]

The existence of canal-like features was definitively disproved in the 1960s by NASA's Mariner missions. Mariner 4, 6, and 7, and the Mariner 9 orbiter (1972), did not capture images of canals but instead showed a cratered Martian surface. Today, the surface markings taken to be canals are regarded as an optical illusion.[16]

Venus spokes

Although Lowell was better known for his observations of Mars, he also drew maps of the planet Venus. He began observing Venus in detail in mid-1896 soon after the 61-centimetre (24-inch) Alvan Clark & Sons refracting telescope was installed at his new Flagstaff, Arizona observatory. Lowell observed the planet high in the daytime sky with the telescope's lens stopped down to 3 inches in diameter to reduce the effect of the turbulent daytime atmosphere. Lowell observed spoke-like surface features including a central dark spot, contrary to what was suspected then (and known now): that Venus has no surface features visible from Earth, being covered in an atmosphere that is opaque. It has been noted in a 2003 Journal for the History of Astronomy paper and in an article published in Sky and Telescope in July 2003 that Lowell's stopping down of the telescope created such a small exit pupil at the eyepiece, it may have become a giant ophthalmoscope giving Lowell an image of the shadows of blood vessels cast on the retina of his eye.[17][18]

Pluto

Lowell's greatest contribution to planetary studies came during the last decade of his life, which he devoted to the search for Planet X, a hypothetical planet beyond Neptune. Lowell believed that the planets Uranus and Neptune were displaced from their predicted positions by the gravity of the unseen Planet X.[19] Lowell started a search program in 1906 using a camera 5 inches (13 cm) in aperture.[20] The small field of view of the 42-inch (110 cm) reflecting telescope rendered the instrument impractical for searching.[20] From 1914 to 1916, a 9-inch (23 cm) telescope on loan from Sproul Observatory was used to search for Planet X.[20] Although Lowell did not discover Pluto, Lowell Observatory (690) did photograph Pluto in March and April 1915.[21]

In 1930 Clyde Tombaugh, working at the Lowell Observatory, discovered Pluto near the location expected for Planet X. Partly in recognition of Lowell's efforts, a stylized P-L monogram (![]() ) – the first two letters of the new planet's name and also Lowell's initials – was chosen as Pluto's astronomical symbol.[19] However, it would subsequently emerge that the Planet X theory was mistaken.

) – the first two letters of the new planet's name and also Lowell's initials – was chosen as Pluto's astronomical symbol.[19] However, it would subsequently emerge that the Planet X theory was mistaken.

Pluto's mass could not be determined until 1978, when its satellite Charon was discovered. This confirmed what had been increasingly suspected: Pluto's gravitational influence on Uranus and Neptune is negligible, certainly not nearly enough to account for the discrepancies in their orbits.[22] In 2006, Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union.

In addition, it is now known that the discrepancies between the predicted and observed positions of Uranus and Neptune were not caused by the gravity of an unknown planet. Rather, they were due to an erroneous value for the mass of Neptune. Voyager 2's 1989 encounter with Neptune yielded a more precise value of its mass, and the discrepancies disappear when using this value.[23]

Legacy

Although Lowell's theories of the Martian canals, of surface features on Venus, and of Planet X are now discredited, his practice of building observatories at the position where they would best function has been adopted as a principle.[19] He also established the program and setting which made the discovery of Pluto by Clyde Tombaugh possible.[24] Craters on the Moon and on Mars have been named after him. Lowell has been described by other planetary scientists as "the most influential popularizer of planetary science in America before Carl Sagan".[25]

While eventually disproved, Lowell's vision of the Martian canals, as an artifact of an ancient civilization making a desperate last effort to survive, significantly influences the development of science fiction – starting with H. G. Wells' influential The War of the Worlds, which made the further logical inference that creatures from a dying planet might seek to invade Earth.

The image of the dying Mars and its ancient culture was retained, in numerous versions and variations, in most SF works depicting Mars in the first half of the twentieth century (see Mars in fiction). Even when proven to be factually mistaken, the vision of Mars derived from his theories remains enshrined in works that remain in print and widely read as classics of science fiction.

Lowell's influence on science fiction remains strong. The canals figure prominently in Red Planet by Robert A. Heinlein (1949) and The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury (1950). The canals, and even Lowell's mausoleum, heavily influence The Gods of Mars (1918) by Edgar Rice Burroughs as well as all other books in the Barsoom series.

The Lowell Regio on Pluto was named in his honour.

Publications

- Percival Lowell Collected Writings on Japan and Asia, including Letters to Amy Lowell and Lafcadio Hearn, 5 vols., Tokyo: Edition Synapse. ISBN 978-4-901481-48-9 www.aplink.co.jp/synapse/4-901481-48-7.htm

- Percival Lowell (1886). Chosön: The Land of the Morning Calm ; a Sketch of Korea. Ticknor.

- Percival Lowell The Evolution of Worlds (1910) (Full text at

The Evolution of Worlds.)

The Evolution of Worlds.)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Chosön, the Land of the Morning Calm; a Sketch of Korea". World Digital Library. 1888. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Littmann, Mark (1985). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier. pp. 62–3. ISBN 0-486-43602-0.

- ↑ Balik, Rachel (March 13, 2010) Happy Birthday Percival Lowell, First Man to Imagine Life on Mars. findingdulcinea.com

- 1 2 Leonard, Louise. Percival Lowell: An Afterglow. RG Badger, 1921, pp. 33, 46.

- ↑

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Lowell, Percival". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Lowell, Percival". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. - ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter L" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ↑ Croswell, Kenneth (1997) Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems. p. 49. ISBN 0684832526.

- ↑ Strauss, David (2001). Percival Lowell: The Culture and Science of a Boston Brahmin. Harvard University Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780674002913.

Though Lowell claimed to "stick to the church" (doubtless from my early religious training)," he was an agnostic and hostile to Christianity.

- ↑ Chambers, P. (1999). Life on Mars; The Complete Story. London: Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-2747-0.

- ↑ Kidger, Mark (2005) Astronomical Enigmas: Life on Mars, the Star of Bethlehem, and Other Milky Way Mysteries. p. 110. ISBN 0801880262.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (October 1, 2015). "Life on Mars? You Read It Here First.". New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9. pp. 355–6.

- ↑ Croswell, Kenneth (1997) Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems. p. 48. ISBN 0684832526.

- ↑ Kidger, Mark (2005) Astronomical Enigmas: Life on Mars, the Star of Bethlehem, and Other Milky Way Mysteries. p. 111. ISBN 0801880262.

- ↑ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 356. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ↑ Baxter, Stephen (2005). Glenn Yeffeth, ed. "H.G. Wells' Enduring Mythos of Mars". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic. BenBalla: 186–7. ISBN 1-932100-55-5.

- ↑ SkyandTelescope.com – News from Sky & Telescope – Venus Spokes: An Explanation at Last?

- ↑ Sheehan, W. & Dobbins, T., The spokes of Venus: an illusion explained, Journal for the History of Astronomy (ISSN 0021-8286), Vol. 34, Part 1, No. 114, p. 53 – 63 (2003) via SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS)

- 1 2 3 Rabkin, Eric S. (2005). Mars: a tour of the human imagination. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 95. ISBN 0-275-98719-1.

- 1 2 3 Tombaugh, C. W. (1946). "The Search for the Ninth Planet, Pluto". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 5: 73–80. Bibcode:1946ASPL....5...73T.

- ↑ Buie, Marc W. (August 11, 2008). "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 134340". SwRI (Space Science Department). Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ↑ Kutner, Marc Leslie (2003). Astronomy: A Physical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 523. ISBN 0-521-52927-1.

- ↑ Standage, Tom (2000) The Neptune File: A Story of Astronomical Rivalry and the Pioneers of Planet Hunting. ISBN 0802713637. p. 188

- ↑ Shaw, H. R. (1994). Craters, Cosmos, and Chronicles: A New Theory of Earth. Stanford University Press. p. 494. ISBN 0-8047-2131-9.

- ↑ Zahnle, K.; Arndt, Nick; Cockell, Charles; Halliday, Alex; Nisbet, Euan; Selsis, Franck; Sleep, Norman H. (2007). "Emergence of a Habitable Planet". Space Science Review. 129 (1–3): 35–78. Bibcode:2007SSRv..129...35Z. doi:10.1007/s11214-007-9225-z.

Further reading

- K., Zahnel (2001). "Decline and Fall of the Martian Empire". Nature. 412 (6843): 209–213. doi:10.1038/35084148. PMID 11449281.

- R., Crossley (2000). "Percival Lowell and the history of Mars". Massachusetts Review. 41 (3): 297–318.

- D., Strauss (1994). "Lowell, Percival, Pickering, W. H. and the founding of the Lowell Observatory". Annals of Science. 51 (1): 37–58. doi:10.1080/00033799400200121.

- J., Trefil (1988). "Turn-of-the-Century American Astronomer Lowell, Percival". Smithsonian. 18 (10): 34–.

- B., Meyer W. (1984). "Life on Mars is almost Certain + Lowell,Percival on Exobiology". American Heritage. 35 (2): 38–43.

- S., Hetherington N. (1981). "Lowell, Percival – Professional Scientist or Interloper". Journal of the History of Ideas. 42 (1): 159–161. doi:10.2307/2709423. JSTOR 2709423.

- C., Heffernan W. (1981). "Lowell, Percival and the Debate over Extraterrestrial Life". Journal of the History of Ideas. 42 (3): 527–530. doi:10.2307/2709191. JSTOR 2709191.

- Webb G. E. (1980). "The Planet Mars and Science in Victorian America". Journal of American Culture. 3 (4): 573. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1980.0304_573.x.

- Hoyt W. G.; G., Wesley W. (1977). "Lowell and Mars". American Journal of Physics. 45 (3): 316–317. Bibcode:1977AmJPh..45..316H. doi:10.1119/1.10630.

- K., Hofling C. (1964). "Percival Lowell and the Canals of Mars". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 37 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1964.tb01304.x.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Percival Lowell |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Percival Lowell |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Percival Lowell. |

- Works by Percival Lowell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Percival Lowell at Internet Archive

- Lowell Observatory

- BBC Science: Percival Lowell

- Percival Lowell at Find a Grave