Panopticon

The Panopticon is a type of institutional building designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all (pan-) inmates of an institution to be observed (-opticon) by a single watchman without the inmates being able to tell whether or not they are being watched. Although it is physically impossible for the single watchman to observe all cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that all inmates must act as though they are watched at all times, effectively controlling their own behaviour constantly. The name is also a reference to Panoptes from Greek mythology; he was a giant with a hundred eyes and thus was known to be a very effective watchman.

The design consists of a circular structure with an "inspection house" at its centre, from which the manager or staff of the institution are able to watch the inmates, who are stationed around the perimeter. Bentham conceived the basic plan as being equally applicable to hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, and asylums, but he devoted most of his efforts to developing a design for a Panopticon prison. It is his prison that is now most widely meant by the term "panopticon".

Bentham himself described the Panopticon as "a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example."[1] Elsewhere, in a letter, he described the Panopticon prison as "a mill for grinding rogues honest".[2]

Conceptual history

Morals reformed—health preserved—industry invigorated—instruction diffused—public burthens lightened—Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock—the Gordian Knot of the poor-law not cut, but untied—all by a simple idea in Architecture![1]

In 1786 and 1787, Bentham travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modern Belarus) to visit his brother, Samuel, who was engaged in managing various industrial and other projects for Prince Potemkin. It was Samuel (as Jeremy later repeatedly acknowledged) who conceived the basic idea of a circular building at the hub of a larger compound as a means of allowing a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large and unskilled workforce.[3][4] Jeremy began to develop this model, particularly as applicable to prisons, and outlined his ideas in a series of letters sent home to his father in England.[5] He supplemented the supervisory principle with the idea of contract management; that is, an administration by contract as opposed to trust, where the director would have a pecuniary interest in lowering the average rate of mortality.[6]

The Panopticon was intended to be cheaper than the prisons of his time, as it required fewer staff; "Allow me to construct a prison on this model," Bentham requested to a Committee for the Reform of Criminal Law, "I will be the gaoler. You will see... that the gaoler will have no salary—will cost nothing to the nation." As the watchmen cannot be seen, they need not be on duty at all times, effectively leaving the watching to the watched. According to Bentham's design, the prisoners would also be used as menial labour walking on wheels to spin looms or run a water wheel. This would decrease the cost of the prison and give a possible source of income.[7]

The abortive Panopticon prison project

On his return to England from Russia, Bentham continued to work on the idea of a Panopticon prison, and commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley.[8] In 1791, he published the material he had written as a book, although he continued to refine his proposals for many years to come. He had by now decided that he wanted to see the prison built: when finished, it would be managed by himself as contractor–governor, with the assistance of Samuel. After unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and revolutionary France,[9] he started trying to persuade the prime minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a Panopticon. He was eventually successful in winning over Pitt and his advisors, and in 1794 was paid £2,000 for preliminary work on the project.[10]

The intended site was one that had been authorised (under an act of 1779) for the earlier Penitentiary, at Battersea Rise; but the new proposals ran into technical legal problems and objections from the local landowner, Earl Spencer.[11] Other sites were considered, including one at Hanging Wood, near Woolwich, but all proved unsatisfactory.[12] Eventually Bentham turned to a site at Tothill Fields, near Westminster. Although this was common land, with no landowner, there were a number of parties with interests in it, including Earl Grosvenor, who owned a house on an adjacent site and objected to the idea of a prison overlooking it. Again, therefore, the scheme ground to a halt.[13] At this point, however, it became clear that a nearby site at Millbank, adjoining the Thames, was available for sale, and this time things ran more smoothly. Using government money, Bentham bought the land on behalf of the Crown for £12,000 in November 1799.[14]

From his point of view, the site was far from ideal, being marshy, unhealthy, and too small. When he asked the government for more land and more money, however, the response was that he should build only a small-scale experimental prison—which he interpreted as meaning that there was little real commitment to the concept of the Panopticon as a cornerstone of penal reform.[15] Negotiations continued, but in 1801 Pitt resigned from office, and in 1803 the new Addington administration decided not to proceed with the project.[16] Bentham was devastated: "They have murdered my best days."[17]

Nevertheless, a few years later the government revived the idea of a National Penitentiary, and in 1811 and 1812 returned specifically to the idea of a Panopticon.[18] Bentham, now aged 63, was still willing to be governor. However, as it became clear that there was still no real commitment to the proposal, he abandoned hope, and instead turned his attentions to extracting financial compensation for his years of fruitless effort. His initial claim was for the enormous sum of nearly £700,000, but he eventually settled for the more modest (but still considerable) sum of £23,000.[19] An Act of Parliament in 1812 transferred his title in the site to the Crown.[20]

Bentham remained bitter about the rejection of the Panopticon scheme throughout his later life, convinced that it had been thwarted by the King and an aristocratic elite. It was largely because of his sense of injustice that he developed his ideas of "sinister interest"—that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest—which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.[21]

The National Penitentiary was indeed subsequently built on the Millbank site, but to a design by William Williams that owed little to the Panopticon, beyond the fact that the governor's quarters, administrative offices, and chapel were placed at the centre of the complex. It opened in 1816.

Panopticon prison designs

The building circular—A cage, glazed—a glass lantern about the Size of Ranelagh—The prisoners in their cells, occupying the circumference—The officers in the centre. By blinds and other contrivances, the inspectors concealed […] from the observation of the prisoners: hence the sentiment of a sort of omnipresence—The whole circuit reviewable with little, or if necessary without any, change of place. One station in the inspection part affording the most perfect view of every cell.— Jeremy Bentham, 1798[22]

The architecture incorporates a tower central to a circular building that is divided into cells, each cell extending the entire thickness of the building to allow inner and outer windows. The occupants of the cells are thus backlit, isolated from one another by walls, and subject to scrutiny both collectively and individually by an observer in the tower who remains unseen. Toward this end, Bentham envisioned not only venetian blinds on the tower observation ports but also maze-like connections among tower rooms to avoid glints of light or noise that might betray the presence of an observer.— Ben and Marthalee Barton, 1993[23]

No true Panopticon prisons to Bentham's designs have ever been built.

The closest (circular and with a panoptic tower) are: the buildings of the now-abandoned Presidio Modelo in Cuba (constructed 1926–28); Pavilhão de Segurança, 1896, architect José Maria Nepomuceno, now part of an Outsider Art and Science museum, in Miguel Bombarda Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal (national monumente); Autun penitentiary, France; Breda and Arnhem penitentiaries, 1884, architect Johan Frederik Metzlaar, Netherlands; Haarlem penitentiary, 1901, Netherlands; Stateville Penitentiary, 1919, Illinois, USA, architect C. Harrick Hammond.[24]

Although most prison designs have included elements of surveillance, the essential elements of Bentham's design were not only that the custodians should be able to view the prisoners at all times (including times when they were in their cells), but also that the prisoners should be unable to see the custodians, and so could never be sure whether or not they were under surveillance.

This objective was extremely difficult to achieve within the constraints of the available technology, which explains why Bentham spent so many years reworking his plans. Subsequent 19th-century prison designs enabled the custodians to keep the doors of cells and the outsides of buildings under observation, but not to see the prisoners in their cells. Something close to a realization of Bentham's vision only became possible through 20th-century technological developments—notably closed-circuit television (CCTV)—but these eliminated the need for a specific architectural framework.

It has been argued that the Panopticon influenced the radial design of 19th-century prisons built on the principles of the "separate system" (including Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, opened in 1829, and the later Pentonville Prison in London and Armagh Gaol in Northern Ireland).[25] In these prisons control was exercised through strict prisoner isolation rather than surveillance, but they also incorporated a design of radiating wings, allowing a centrally located guard to observe the door of every cell.

Prisons for which a "Panoptic" influence has been claimed

As noted, none of these prisons—with the arguable exceptions mentioned above—are true Panopticons in the Benthamic sense. In some cases, the claims for any influence are very dubious indeed, and seem to be based on little more than the fact that (for example) the design is circular.

- Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

- Pavilhão de Segurança (Security Pavilion), now a Museum of Patient and Outsider Art and Science, of Miguel Bombarda Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal[26]

- hu:Balassagyarmat Fegyház és Börtön (Prison) – Balassagyarmat, Hungary

- The Bridewell – Edinburgh, Scotland (by Robert Adam, 1791: now demolished)[27]

- Carabanchel Prison – Madrid, Spain (now demolished)

- Palacio de Justicia y Cárcel de Vigo (now Museo de Arte Contemporánea) – Vigo, Spain

- Caseros Prison – Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Palacio de Lecumberri – Mexico City, Mexico

- Chi Hoa – Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- Fleury-Mérogis Prison – Fleury-Mérogis, France.[28][29]

- Huron Historic Gaol – Goderich, Ontario, Canada

- Insein Prison – Insein, Burma

- Kilmainham Gaol – Dublin, Ireland

- Koepelgevangenis (Arnhem) – Arnhem, Netherlands (Koepelgevangenis literally means dome-prison)

- Koepelgevangenis (Breda) – Breda,Netherlands

- Koepelgevangenis (Haarlem) – Haarlem, Netherlands

- Lancaster Castle Gaol (extensions by Joseph Gandy of 1818–21) – Lancaster, England[30]

- Prisión Modelo – Barcelona, Spain

- Mount Eden Prisons – Auckland, New Zealand

- Okrąglak Areszt Śledczy w Toruniu – Toruń, Poland

- Old Bilibid Prison – Manila City Jail, Philippines[31]

- Old Provost – Grahamstown, South Africa

- Panóptico de Cundinamarca – Bogotá, Colombia (today the National Museum of Colombia)

- Pelican Bay State Prison – Del Norte County, California, United States

- Port Arthur, Tasmania Prison Colony – Port Arthur, Tasmania, Australia

- Pentridge Prison airing yards, Melbourne[32]

- Presidio Modelo – Isla de la Juventud, Cuba

- Corradino Correctional Facilities – Paola, Malta

- Round House – Fremantle, Western Australia, Australia – although not a Panopticon, this circular prison building of 1830 was designed by Henry Willey Reveley, the son of Bentham's architect collaborator, Willey Reveley.

- Special Handling Unit – Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines,[33] Quebec, Canada

- Stateville Correctional Center – Crest Hill, IL, United States

- Twin Towers Correctional Facility – Los Angeles, CA, United States

- Sachsenhausen concentration camp – Oranienburg, Germany[34]

- Lapas Sukamiskin – Bandung, Indonesia

- The Circle at Parramatta Prison – Sydney, Australia[35]

Other panoptic structures

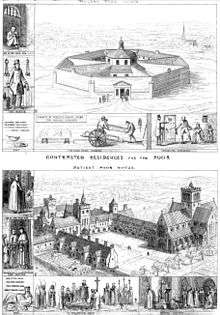

Bentham always conceived the Panopticon principle as being beneficial to the design of a variety of institutions where surveillance was important, including hospitals, schools, workhouses, and lunatic asylums, as well as prisons. In particular, he developed it in his ideas for a "chrestomathic" school (one devoted to useful learning), in which teaching was to be undertaken by senior pupils on the monitorial principle, under the overall supervision of the Master;[36] and for a pauper "industry-house" (workhouse).[37][38]

A wooden Panopticon factory, capable of holding 5000 workers, was constructed by Samuel Bentham in Saint Petersburg, on the banks of the Neva River, between 1805 and 1808: its purpose was to educate and employ young men in trades connected with the navy. It burned down in 1818.[39]

The Round Mill in Belper, Derbyshire, England, is supposed to have been built on the Panopticon principle with a central overseer. Designed by William Strutt, and constructed in 1811, it had fallen into disuse by the beginning of the 20th century and was demolished in 1959.[40]

The Worcester State Hospital, constructed in the late 19th century, extensively employed panoptic structures to allow more efficient observation of the wards. It was considered a model facility at the time.

The Panopticon has been suggested as an "open" hospital architecture:

Hospitals required knowledge of contacts, contagions, proximity and crowding ... at the same time to divide space and keep it open, assuring a surveillance which is both global and individualising.— 1977 interview (preface to French edition of Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon)[41]

Criticism and the Panopticon as metaphor

Despite the fact that no Panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime (and virtually none since), his concept has prompted considerable discussion and debate. Whereas Bentham himself regarded the Panopticon as a rational, enlightened, and therefore just, solution to societal problems, his ideas have been repeatedly criticised by others for their reductive, mechanistic and inhumane approach to human lives. Thus, in 1841, Augustus Pugin published the second edition of his work Contrasts in which one plate showed a "Modern Poor House" (clearly modelled on a Panopticon), a bleak and comfortless structure in which the pauper is separated from his family, subjected to a harsh discipline, fed on a minimal diet, and consigned after death to medical dissection, contrasted with an "Antient Poor House", an architecturally inspiring religious institution in which the pauper is treated throughout with humanity and dignity.[42] In 1965, American historian Gertrude Himmelfarb published an essay, "The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham", in which she depicted Bentham's mechanism of surveillance as a tool of oppression and social control.[43] Parallel arguments were put forward by French psychoanalyst Jacques-Alain Miller in an essay entitled "Le despotisme de l'utile: la machine panoptique de Jeremy Bentham", written in 1973 and published in 1975.[44][45]

Most influentially, the idea of the panopticon was invoked by Michel Foucault, in his Discipline and Punish (1975), as a metaphor for modern "disciplinary" societies and their pervasive inclination to observe and normalise. "On the whole, therefore, one can speak of the formation of a disciplinary society in this movement that stretches from the enclosed disciplines, a sort of social 'quarantine', to an indefinitely generalizable mechanism of 'panopticism'".[46] The Panopticon is an ideal architectural figure of modern disciplinary power. The Panopticon creates a consciousness of permanent visibility as a form of power, where no bars, chains, and heavy locks are necessary for domination any more.[47] Foucault proposes that not only prisons but all hierarchical structures like the army, schools, hospitals and factories have evolved through history to resemble Bentham's Panopticon. The notoriety of the design today (although not its lasting influence in architectural realities) stems from Foucault's famous analysis of it.

Building on Foucault, contemporary social critics often assert that technology has allowed for the deployment of panoptic structures invisibly throughout society. Surveillance by CCTV cameras in public spaces is an example of a technology that brings the gaze of a superior into the daily lives of the populace. Furthermore, a number of cities in the United Kingdom, including Middlesbrough, Bristol, Brighton and London have added loudspeakers to a number of their existing CCTV cameras. They can transmit the voice of a camera supervisor to issue audible messages to the public.[48][49] Similarly, critical analyses of internet practice have suggested that the internet allows for a panoptic form of observation.[50] ISPs are able to track users' activities, while user-generated content means that daily social activity may be recorded and broadcast online.[51]

Shoshana Zuboff used the metaphor of the panopticon in her book In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power (1988) to describe how computer technology makes work more visible. Zuboff examined how computer systems were used to track the behavior and output of workers. She used the term panopticon because the workers could not tell that they were being spied on, while the manager was able to check their work continuously. As the book was written in 1988, Zuboff's arguments were based on Dialog rather than the World Wide Web. Zuboff argued that there is a collective responsibility formed by the hierarchy in the Information Panopticon that eliminates subjective opinions and judgements of managers on their employees. Because each employee's contribution to the production process is translated into objective data, it becomes more important for managers to be able to analyze the work rather than analyze the people.[52]

In 1991 Mohammad Kowsar used the metaphor in the title of his book The Critical Panopticon: Essays in the Theatre and Contemporary Aesthetics, American University Studies (XXVI. Theatre Arts). Derrick Jensen and Gerge Draffan's 2004 book Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control seeks to demonstrate how our society, by techniques like the use of biometric passports to identity chips in consumer goods, from nanoparticle weapons to body-enhancing and mind-altering drugs for soldiers, is being pushed towards a panopticon-like state.

In his 1998 essay, "The Baha’i Faith in America as Panopticon, 1963–1997," academic Juan Cole compares the Bahá'í administration's control over members of the Baha'i faith to panopticon.[53]

The panopticon has also become a symbol of the extreme measures that some companies take in the name of efficiency as well as to guard against employee theft, documented in a 2009 paper by Max Haiven and Scott Stoneman entitled Wal-Mart: The Panopticon of Time[54] and the 2014 book by Simon Head, Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans[55] that describes conditions at an Amazon.com depot in Augsburg, Germany. Both argue that catering at all times to the desires of the customer can lead to increasingly oppressive corporate environments and quotas in which many warehouse workers can no longer keep up with demands of management.

Social theorist Simone Browne reviews Bentham's theories in her book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015).[56] She notes that Bentham travelled on a ship carrying a cargo of what he calls "18 young Negresses" while drafting his Panopticon proposal, and argues that the structure of chattel slavery haunts the theory of the Panopticon. She proposes that the plan of the slave ship Brookes, produced and distributed by the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1789, should be regarded as the paradigmatic blueprint for what she calls "racializing surveillance."

Literature and the arts

- In Gabriel García Márquez's novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), the Vicario brothers spend three years in the "panopticon of Riohacha" awaiting trial for the murder of Santiago Nasar.

- Angela Carter includes a critique of the Panopticon prison system during the Siberian segment of her novel Nights at the Circus (1984).

- Charles Stross's novel Glasshouse (2006) features a technology-enabled panopticon as the novel's primary location.

- In DC Comics' JLA: Earth 2, the Crime Syndicate of Amerika operates from a lunar base known as the Panopticon, from which they routinely observe everyone and everything on the Anti-matter Earth.

- In Battlefield 4, one of the single-player missions and multi-player maps features a prison constructed in the panopticon style.

- In Batman: Arkham Origins, Blackgate prison has a panopticon within the facility; and Batman refers to himself, in a sense, as a metaphorical panopticon to criminals and corrupt cops.

- Although not directly named, the telescreens which are omnipresent in Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) of which "there was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment... you had to live... in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised."[57] are based on the founding principle of the Panopticon.

- In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Justice," law on the planet Rubicun III closely follows the idea of the Panopticon, with lawmen known as overseers are randomly assigned to a given area at a given time. If a citizen commits any crime and falls within the randomly changing areas of the overseers, the citizen will be given the death penalty.

- The third location visited in Konami's 2004 video game Silent Hill 4: The Room is a cylindrical prison modeled on the panopticon, used by a cult to imprison and observe orphaned children in cells arranged around a central guardhouse.

- In the TV series Doctor Who, the centre of the Time Lord's capitol on Gallifrey is known as "The Panopticon". It featured heavily in the stories The Deadly Assassin and The Invasion of Time.

- In the collectible card game Magic: The Gathering, the plane of Mirrodin features a structure called The Panopticon from where its warden Memnarch controlled his artifact minions and watched over his world through the eyes of his creations, the myr.[58]

- The video game Freedom Wars features colossal, futuristic panopticons that are direct descendents of Bentham's original idea in which thousands of "sinners" are imprisoned and kept under constant surveillance.

- In Guardians of the Galaxy (film), the Kyln, a Nova Corps prison, is based on a Panopticon.

- In The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks, the Panopticon is repeatedly mentioned.

- In Civilization: Beyond Earth, the Panopticon can be constructed as a wonder.

- The third studio album of the American post-metal band ISIS is entitled "Panopticon".

See also

- Panopticism

- Total institution

- Hawthorne effect (observer effect)

- Social facilitation

- Mass surveillance

- PRISM (surveillance program)

- Right to privacy

- Sousveillance

References

- 1 2 Bentham 1843d, p. 39.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (1843), The Works, 10. Memoirs Part I and Correspondence, Liberty fund

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Roth, Mitchel P (2006), Prisons and prison systems: a global encyclopedia, Greenwood, p. 33, ISBN 9780313328565

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 134–40.

- ↑ Bentham 1995, pp. 29–95.

- ↑ Semple 1993, p. 118.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 102–4, 107–8.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 108–10, 262.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 169–89.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 194–7.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 197–217.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 217–22.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 226–31.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 236–9.

- ↑ Semple 1993, p. 244.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 265–79.

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 279–81.

- ↑ Penitentiary House, etc. Act: 52 Geo. III, c. 44 (1812).

- ↑ Schofield, Philip (2009). Bentham: a guide for the perplexed. London: Continuum. pp. 90–93. ISBN 978-0-8264-9589-1.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (1798), Proposal for a New and Less Expensive mode of Employing and Reforming Convicts; quoted in Evans 1982, p. 195.

- ↑ Barton, Ben F.; Barton, Marthalee S. (1993). "Modes of Power in Technical and Professional Visuals". Journal of Business and Technical Communication. 7 (1): 138–62. doi:10.1177/1050651993007001007.

- ↑ Freire, Vitor Albuquerque (2009). Panóptico, Vanguardista e Ignorado. O Pavilhão de Segurança do Hospital Miguel Bombarda. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

- ↑ Andrzejewski, Anna Vemer (2008). Building Power: Architecture and Surveillance in Victorian America. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-57233631-5.

- ↑ Freire, Vítor Albuquerque, Panóptico, Vanguardista e Ignorado. O Pavilhão de Segurança do Hospital Miguel Bombarda, Libros Horizonte, Lisbon, 2009.

- ↑ Evans 1982, pp. 228, 231.

- ↑ The penitential center, the largest prison in Europe, FR: Mairie de Fleury-Mérogis, archived from the original on 4 December 2007.

- ↑ Macey, David (2004). Michel Foucault (Critical Lives ed.). Reaktion Books. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-86189226-3.

- ↑ Evans 1982, pp. 228, 232.

- ↑ "Manila landmarks of the '30s", Philstar, 9 July 2005.

- ↑ Pentridge Prison's Panopticon (podcast) (1), Tempus, 7 October 2014.

- ↑ SAdP, QC, CA: CSC SCC.

- ↑ Allen, Michael Thad (2002). The Business of Genocide: the SS, slave labor, and the concentration camps. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-80782677-4.

[Theodor Eicke] had organized Sachsenhausen on the principles of a panopticon

. - ↑ NSW jails (JPEG) (image), AU: USQ.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (1983). Smith, M. J.; Burston, W. H., eds. Chrestomathia. Collected Works. Oxford. pp. 106, 108–9, 124..

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (2010). Quinn, Michael, ed. Writings on the Poor Laws. Collected Works. 2. Oxford. pp. 98–9, 105–6, 112–3, 352–3, 502–3..

- ↑ Bahmueller, C. F. (1981). The National Charity Company: Jeremy Bentham's Silent Revolution. Berkeley..

- ↑ Semple 1993, pp. 214–5..

- ↑ Farmer, Adrian (2004). Belper and Milford. Stroud: Tempus. p. 119.

- ↑ Elden, Stuart (2002). "Plague, Panopticon, Police". Surveillance & Society. Kingston, ON, CA: Queen's University. 1 (3): 243 (3 of the PDF). Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Belcher, Margaret (1994). "Pugin Writing". In Atterbury, Paul; Wainwright, Clive. Pugin: a Gothic Passion. London: Yale University Press. pp. 105–16 (108–9). ISBN 0-30006012-2.

- ↑ Himmelfarb, Gertrude (1965). "The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham". In Herr, Richard; Parker, Harold T. Ideas in History: essays presented to Louis Gottschalk by his former students. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- ↑ Miller, Jacques-Alain (1975). "La despotisme de l'utile: la machine panoptique de Jeremy Bentham" [The despotism of the useful: Jeremy Bentham’s panoptical machine]. Ornicar? (in French). 3: 3–36.; published in English as Miller, Jacques-Alain (1987). "Jeremy Bentham's Panoptic Device". October. 41.

- ↑ Jay, Martin (1993). Downcast eyes: the denigration of vision in twentieth-century French thought. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 381–4. ISBN 0-52008154-4..

- ↑ Foucault 1995, pp. 195–210: quotation at p. 216.

- ↑ Allmer, Thomas (2012), Towards a Critical Theory of Surveillance in Informational Capitalism, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, p. 22.

- ↑ "Cameras Help Stop Crime", The Hoya, 22 September 2006.

- ↑ 2006, But Has 1984 Finally Arrived?, UK: Indymedia, 19 September 2006.

- ↑ "The New Panopticon: The Internet Viewed as a Structure of Social Control", Theory & science, ICAAP, 3 (1)

- ↑ "Workshop: Exploring the Impact of User-generated Mobile Content – The Participatory Panopticon". Mobi mundi. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ Zuboff, Shoshana (1988), In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power (PDF), New York: Basic Books, pp. 315–61

- ↑ Cole, Juan (June 1998). "The Baha'i Faith in America as Panopticon, 1963-1997". The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 37 (2): 234–238. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ Haiven, Max; Stoneman, Scott (2009), Wal-Mart: The Panopticon of Time (PDF), pp. 3–7.

- ↑ Head, Simon (2014). "Walmart and Amazon". In Bartlett, Tim. Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Makes Dumber Humans. New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN 0-46501844-0.

- ↑ Browne, Simone (2015). Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822359197.

- ↑ Orwell, George (1989) [1949], Nineteen Eighty-Four, Penguin, pp. 4, 5.

- ↑ "Panopticon", Magic: The Gathering salvation, Gamepedia.

Bibliography

- Bentham, Jeremy (1843d), The Works, 4. Panopticon, Constitution, Colonies, Codification, Liberty fund.

- ——— (1995). Božovič, Miran, ed. The Panopticon Writings. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984958-X.

- Evans, Robin (1982). The Fabrication of Virtue: English prison architecture, 1750–1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–235. ISBN 0-52123955-9.

- Foucault, Michel (1995). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-67975255-2.

- Semple, Janet (1993). Bentham's Prison: a Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19827387-8.

External links

- Bentham, Jeremy (1843), Bowring, John, ed., The Works, 4, Edinburgh: William Tait. This is the volume that contains Bentham's writings on the Panopticon.

- ———, Panopticon (online ed.), Cartome.

- Panopticon; or, The inspection house: on the Internet Archive

- Cascio, Jamais (2005), The Rise of the Participatory Panopticon, World changing

- Kimble, Chris, Control and Surveillance from Computers in Society (online course).

- Werrett, Simon, The Panopticon in the Garden (essay), Ab imperio on the Russian origins of the Panopticon

- "The Panopticon", Surveillance and Society (special issue), LI (3).