Pauling's rules

Pauling's rules are five rules published by Linus Pauling in 1929 for predicting and rationalizing the crystal structures of ionic compounds.[1][2]

First rule: the radius ratio rule

For typical ionic solids, the cations are smaller than the anions, and each cation is surrounded by coordinated anions which form a polyhedron. The sum of the ionic radii determines the cation-anion distance, while the cation-anion radius ratio (or ) determines the coordination number (C.N.) of the cation, as well as the shape of the coordinated polyhedron of anions.[3][4]

For the coordination numbers and corresponding polyhedra in the table below, Pauling mathematically derived the minimum radius ratio for which the cation is in contact with the given number of anions (considering the ions as rigid spheres). If the cation is smaller, it will not be in contact with the anions which results in instability leading to a lower coordination number.

| C.N. | Polyhedron | Radius ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | triangular | 0.155 |

| 4 | tetrahedron | 0.225 |

| 6 | octahedron | 0.414 |

| 7 | capped octahedron | 0.592 |

| 8 | square antiprism (anticube) | 0.645 |

| 8 | cube | 0.732 |

| 9 | triaugmented triangular prism | 0.732 |

| 12 | cuboctahedron | 1.00 |

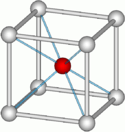

The three diagrams at right correspond to octahedral coordination with a coordination number of six: four anions in the plane of the diagrams, and two (not shown) above and below this plane. The central diagram shows the minimal radius ratio. The cation and any two anions form a right triangle, with , or . Then . Similar geometrical proofs yield the minimum radius ratios for the highly symmetrical cases C.N. = 3, 4 and 8.[5]

For C.N. = 6 and a radius ratio greater than the minimum, the crystal is more stable since the cation is still in contact with six anions, but the anions are further from each other so that their mutual repulsion is reduced. An octahedron may then form with a radius ratio greater than or equal to .414, but as the ratio rises above .732, a cubic geometry becomes more stable. This explains why Na+ in NaCl with a radius ratio of 0.55 has octahedral coordination, whereas Cs+ in CsCl with a radius ratio of 0.93 has cubic coordination.[6]

If the radius ratio is less than the minimum, two anions will tend to depart and the remaining four will rearrange into a tetrahedral geometry where they are all in contact with the cation.

The radius ratio rules are a first approximation which have some success in predicting coordination numbers, but many exceptions do exist.[4]

Second rule: the electrostatic valence rule

For a given cation, Pauling defined[2] the electrostatic bond strength to each coordinated anion as , where z is the cation charge and ν is the cation coordination number. A stable ionic structure is arranged to preserve local electroneutrality, so that the sum of the strengths of the electrostatic bonds to an anion equals the charge on that anion.

where is the anion charge and the summation is over the adjacent cations. For simple solids, the are equal for all cations coordinated to a given anion, so that the anion coordination number is the anion charge divided by each electrostatic bond strength. Some examples are given in the table.

| Cation | Radius ratio | Cation C.N. | Electrostatic bond strength | Anion C.N. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li+ | 0.34 | 4 | 0.25 | 8 |

| Mg2+ | 0.47 | 6 | 0.33 | 6 |

| Sc3+ | 0.60 | 6 | 0.5 | 4 |

Pauling showed that this rule is useful in limiting the possible structures to consider for more complex crystals such as the aluminosilicate mineral orthoclase, KAlSi3O8, with three different cations.[2]

Third rule: sharing of polyhedron corners, edges and faces

The sharing of edges and particularly faces by two anion polyhedra decreases the stability of an ionic structure. Sharing of corners does not decrease stability as much, so (for example) octahedra may share corners with one another.[7]

The decrease in stability is due to the fact that sharing edges and faces places cations in closer proximity to each other, so that cation-cation electrostatic repulsion is increased. The effect is largest for cations with high charge and low C.N. (especially when r+/r- approaches the lower limit of the polyhedral stability).

As one example, Pauling considered the three mineral forms of titanium dioxide, each with a coordination number of 6 for the Ti4+ cations. The most stable (and most abundant) form is rutile, in which the coordination octahedra are arranged so that each one shares only two edges (and no faces) with adjoining octahedra. The other two, less stable, forms are brookite and anatase, in which each octahedron shares three and four edges respectively with adjoining octahedra.[7]

Fourth rule: crystals containing different cations

In a crystal containing different cations, those of high valency and small coordination number tend not to share polyhedron elements with one another.[8] This rule tends to increase the distance between highly charged cations, so as to reduce the electrostatic repulsion between them.

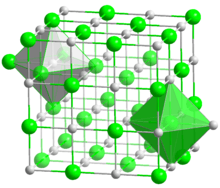

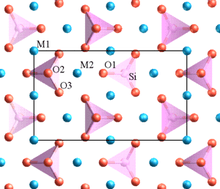

One of Pauling's examples is olivine, M2SiO4, where M is a mixture of Mg2+ at some sites and Fe2+ at others. The structure contains distinct SiO4 tetrahedra which do not share any oxygens (at corners, edges or faces) with each other. The lower-valence Mg2+ and Fe2+ cations are surrounded by polyhedra which do share oxygens.

Fifth rule: the rule of parsimony

The number of essentially different kinds of constituents in a crystal tends to be small. The repeating units will tend to be identical because each atom in the structure is most stable in a specific environment. There may be two or three types of polyhedra, such as tetrahedra or octahedra, but there will not be many different types.

References

- ↑ Pauling, Linus (1929). "The principles determining the structure of complex ionic crystals". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 51 (4): 1010–1026. doi:10.1021/ja01379a006.

- 1 2 3 Pauling, Linus (1960). The nature of the chemical bond and the structure of molecules and crystals; an introduction to modern structural chemistry (3rd ed.). Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press. p. 543-562. ISBN 0-8014-0333-2.

- ↑ Pauling (1960) p.524

- 1 2 Housecroft C.E. and Sharpe A.G. Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed., Pearson Prentice-Hall 2005) p.145 ISBN 0130-39913-2

- ↑ Toofan J. (1994) J. Chem. Educ. 71 (9), 147 (and Erratum p.749) A Simple Expression between Critical Radius Ratio and Coordination Numbers

- ↑ R.H. Petrucci, W.S. Harwood and F.G. Herring, General Chemistry (8th ed., Prentice-Hall 2002) p.518 ISBN 0-13-014329-4

- 1 2 Pauling (1960) p.559

- ↑ Pauling (1960), p.561