Apheresis

| Apheresis | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

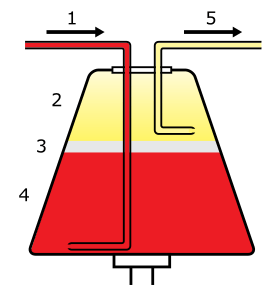

Whole blood enters the centrifuge (1) and separates into plasma (2), leukocytes (3), and erythrocytes (4). Selected components are then drawn off (5). | |

| MeSH | D016238 |

Apheresis (ἀφαίρεσις (aphairesis, "a taking away")) is a medical technology in which the blood of a person is passed through an apparatus that separates out one particular constituent and returns the remainder to the circulation. It is thus an extracorporeal therapy.

Method

Depending on the substance that is being removed, different processes are employed in apheresis. If separation by density is required, centrifugation is the most common method. Other methods involve absorption onto beads coated with an absorbent material and filtration.

The centrifugation method can be divided into two basic categories:

Continuous flow centrifugation

Continuous flow centrifugation (CFC) historically required two venipunctures as the "continuous" means the blood is collected, spun, and returned simultaneously. Newer systems can use a single venipuncture. The main advantage of this system is the low extracorporeal volume (calculated by volume of the apheresis chamber, the donor's hematocrit, and total blood volume of the donor) used in the procedure, which may be advantageous in the elderly and for children.

Intermittent flow centrifugation

Intermittent flow centrifugation works in cycles, taking blood, spinning/processing it and then giving back the unused parts to the donor in a bolus. The main advantage is a single venipuncture site. To stop the blood from coagulating, anticoagulant is automatically mixed with the blood as it is pumped from the body into the apheresis machine.

Centrifugation variables

The centrifugation process itself has four variables that can be controlled to selectively remove desired components. The first is spin speed and bowl diameter, the second is "sit time" in centrifuge, the third is solutes added, and the fourth is not as easily controllable: plasma volume and cellular content of the donor. The end product in most cases is the classic sedimented blood sample with the RBC's at the bottom, the buffy coat of platelets and WBC's (lymphocytes/granulocytes (PMN's, basophils, eosinophils/monocytes) in the middle and the plasma on top.

Types

There are numerous types of apheresis.

Donation

Blood taken from a healthy donor can be separated into its component parts during blood donation, where the needed component is collected and the "unused" components are returned to the donor. Fluid replacement is usually not needed in this type of collection. There are large categories of component collections:

- Plasmapheresis – blood plasma. Plasmapheresis is useful in collecting FFP (fresh frozen plasma) of a particular ABO group. Commercial uses aside from FFP for this procedure include immunoglobulin products, plasma derivatives, and collection of rare WBC and RBC antibodies.

- Erythrocytapheresis – red blood cells. Erythrocytapheresis is the separation of erythrocytes from whole blood. It is most commonly accomplished using the method of centrifugal sedimentation. This process is used for red blood cell diseases such as sickle cell crises or severe malaria. The automated red blood cell collection procedure for donating erythrocytes is referred to as 'Double Reds' or 'Double Red Cell Apheresis.'[1]

- Plateletpheresis (thrombapheresis, thrombocytapheresis) – blood platelets. Plateletpheresis is the collection of platelets by apheresis while returning the RBCs, WBCs, and component plasma. The yield is normally the equivalent of between six and ten random platelet concentrates. Quality control demands the platelets from apheresis be equal to or greater than 3.0 × 1011 in number and have a pH of equal to or greater than 6.2 in 90% of the products tested and must be used within five days.

- Leukapheresis – leukocytes (white blood cells). Leukopheresis is the removal of PMNs, basophils, eosinophils for transfusion into patients whose PMNs are ineffective or where traditional therapy has failed. There is limited data to suggest the benefit of granulocyte infusion. The complications of this procedure are the difficulty in collection and short shelf life (24 hours at 20 to 24 °C). Since the "buffy coat" layer sits directly atop the RBC layer, HES, a sedimenting agent, is employed to improve yield while minimizing RBC collection. Quality control demands the resultant concentrate be 1.0 × 1010 granulocytes in 75% of the units tested and that the product be irradiated to avoid graft-versus-host disease (inactivate lymphocytes). Irradiation does not affect PMN function. Since there is usually a small amount of RBCs collected, ABO compatibility should be employed when feasible.

- Stem cell harvesting – circulating bone marrow cells are harvested to use in bone marrow transplantation.

Donor safety

- Single use kits – Apheresis is done using single-use kits, so there is no risk of infection from blood-contaminated tubing or centrifuge.

- Immune system effects – "the immediate decreases in blood lymphocyte counts and serum immunoglobulin concentrations are of slight to moderate degree and are without known adverse effects. Less information is available regarding long-term alterations of the immune system"[2]

Kit problems

Two apheresis kit recalls were:

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation (2005) in which "pinhole leaks were observed at the two-omega end of the umbilicus (multilumen tubing), causing a blood leak. "[3]

- Fenwal Incorporated (2007) in which there were "two instances where the anticoagulant citrate dextrose (ACD) and saline lines were reversed in the assembly process. The reversed line connections may not be visually apparent in the monitor box, and could result in excessive ACD infusion and severe injury, including death, to the donor."[4]

Plasticizer exposure

Apheresis uses plastics and tubing, which come into contact with the blood. The plastics are made of PVC in addition to additives such as a plasticizer, often DEHP. DEHP leaches from the plastic into the blood, and people have begun to study the possible effects of this leached DEHP on donors as well as transfusion recipients.

- "current risk or preventive limit values for DEHP such as the RfD of the US EPA (20 μg/kg/day) and the TDI of the European Union (20–48 μg/kg/day) can be exceeded on the day of the plateletpheresis. . . . Especially women in their reproductive age need to be protected from DEHP exposures exceeding the above mentioned preventive limit values."[5]

- "Commercial plateletpheresis disposables release considerable amounts of DEHP during the apheresis procedure, but the total dose of DEHP retained by the donor is within the normal range of DEHP exposure of the general population."[6]

- The Baxter company manufactured blood bags without DEHP, but there was little demand for the product in the marketplace[7]

- "Mean DEHP doses for both plateletpheresis techniques (18.1 and 32.3 μg/kg/day) were close to or exceeded the reference dose (RfD) of the US EPA and tolerable daily intake (TDI) value of the EU on the day of the apheresis. Therefore, margins of safety might be insufficient to protect especially young men and women in their reproductive age from effects on reproductivity. At present, discontinuous-flow devices should be preferred to avert conceivable health risks from plateletpheresis donors. Strategies to avoid DEHP exposure of donors during apheresis need to be developed."[8]

Therapy

The various apheresis techniques may be used whenever the removed constituent is causing severe symptoms of disease. Generally, apheresis has to be performed fairly often, and is an invasive process. It is therefore only employed if other means to control a particular disease have failed, or the symptoms are of such a nature that waiting for medication to become effective would cause suffering or risk of complications.

- Plasma exchange – removal of the liquid portion of blood to remove harmful substances. The plasma is replaced with a replacement solution.

- LDL apheresis – removal of low density lipoprotein in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia.

- Photopheresis – used to treat graft-versus-host disease, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and rejection in heart transplantation.

- Immunoadsorbtion with Staphylococcal protein A-agarose column – removal of allo- and autoantibodies (in autoimmune diseases, transplant rejection, hemophilia) by directing plasma through protein A-agarose columns. Protein A is a cell wall component produced by several strains of Staphylococcus aureus which binds to the Fc region of IgG.

- Leukocytapheresis – removal of malignant white blood cells in people with leukemia and very high white blood cell counts causing symptoms.

- Erythrocytapheresis – removal of erythrocytes (red blood cells) in people with iron overload as a result of Hereditary haemochromatosis or transfusional iron overload

- Thrombocytapheresis – removal of platelets in people with symptoms from extreme elevations in platelet count such as those with essential thrombocythemia or polycythemia vera.

Evidence-based guidelines for therapeutic apheresis

In 2010, the American Society for Apheresis published the 5th Special Edition(1)[9] of evidence based guidelines for the practice of Apheresis Medicine. These guidelines are based upon a systematic review of available scientific literature. Clinical utility for a given disease is denoted by assignment of an ASFA Category (I – IV). The quality and strength of evidence are denoted by standard GRADE recommendations. ASFA Categories are defined as follows:

- Category I for disorders where therapeutic apheresis is accepted as a first line treatment,

- Category II for disorders where therapeutic apheresis is accepted as a second-line treatment,

- Category III for disorders where the optimal role of therapeutic apheresis is not clearly established and

- Category IV for disorders where therapeutic apheresis is considered ineffective or harmful.

Fluid replacement during apheresis

When an apheresis system is used for therapy, the system is removing relatively small amounts of fluid (not more than 10.5 mL/kg body weight). That fluid must be replaced to keep correct intravascular volume. The fluid replaced is different at different institutions. If a crystalloid like normal saline (NS) is used, the infusion amount should be triple what is removed as the 3:1 ratio of normal saline for plasma is needed to keep up oncotic pressure. Some institutions use normal serum albumin, but it is costly and can be difficult to find. Some advocate using fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or a similar blood product, but there are dangers including citrate toxicity (from the anticoagulant), ABO incompatibility, infection, and cellular antigens.

See also

References

- ↑ dtm double red cell Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Strauss, Ronald G. (1984). "Apheresis donor safety – changes in humoral and cellular immunity". Journal of Clinical Apheresis. 2 (1): 68–80. doi:10.1002/jca.2920020112. PMID 6536660.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-01-17. Retrieved 2008-12-20. "Recall of Amicus Apheresis Kits, Baxter Healthcare Corporation" , US FDA, Jan 31 2005

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/Recalls/ucm053390.htm "Recall of CS3000 Apheresis Kits", US Food and Drug Administration, June 21, 2007

- ↑ Koch, Holger M.; Bolt, Hermann M.; Preuss, Ralf; Eckstein, Reinhold; Weisbach, Volker; Angerer, Jürgen (2005). "Intravenous exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP): Metabolites of DEHP in urine after a voluntary platelet donation". Archives of Toxicology. 79 (12): 689–93. doi:10.1007/s00204-005-0004-x. PMID 16059725.

- ↑ Buchta, Christoph; Bittner, Claudia; Höcker, Paul; Macher, Maria; Schmid, Rainer; Seger, Christoph; Dettke, Markus (2003). "Donor exposure to the plasticizer di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate during plateletpheresis". Transfusion. 43 (8): 1115–20. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00479.x. PMID 12869118.

- ↑ http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-56958320.html "SO FAR, PHTHALATE ALTERNATIVES HAVEN'T INSPIRED MUCH DEMAND.", Article from: Plastics News, October 25, 1999, Toloken, Steve

- ↑ Koch, Holger M.; Angerer, Jürgen; Drexler, Hans; Eckstein, Reinhold; Weisbach, Volker (2005). "Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) exposure of voluntary plasma and platelet donors". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 208 (6): 489–98. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.07.001. PMID 16325559.

- ↑ Szczepiorkowski, Zbigniew M.; Winters, Jeffrey L.; Bandarenko, Nicholas; Kim, Haewon C.; Linenberger, Michael L.; Marques, Marisa B.; Sarode, Ravindra; Schwartz, Joseph; et al. (2010). "Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice-Evidence-based approach from the apheresis applications committee of the American Society for Apheresis". Journal of Clinical Apheresis. 25 (3): 83–177. doi:10.1002/jca.20240. PMID 20568098.

External links

- NIH

- American Society for Apheresis

- Apheresis in Blood Platelet Donation

- WebPath Apheresis page.

- WebPath Blood Donation and Processing

- Donating Platelet Apheresis: Facts and the FAQ