Philippopolis (Thracia)

| Φιλιππούπολη | |

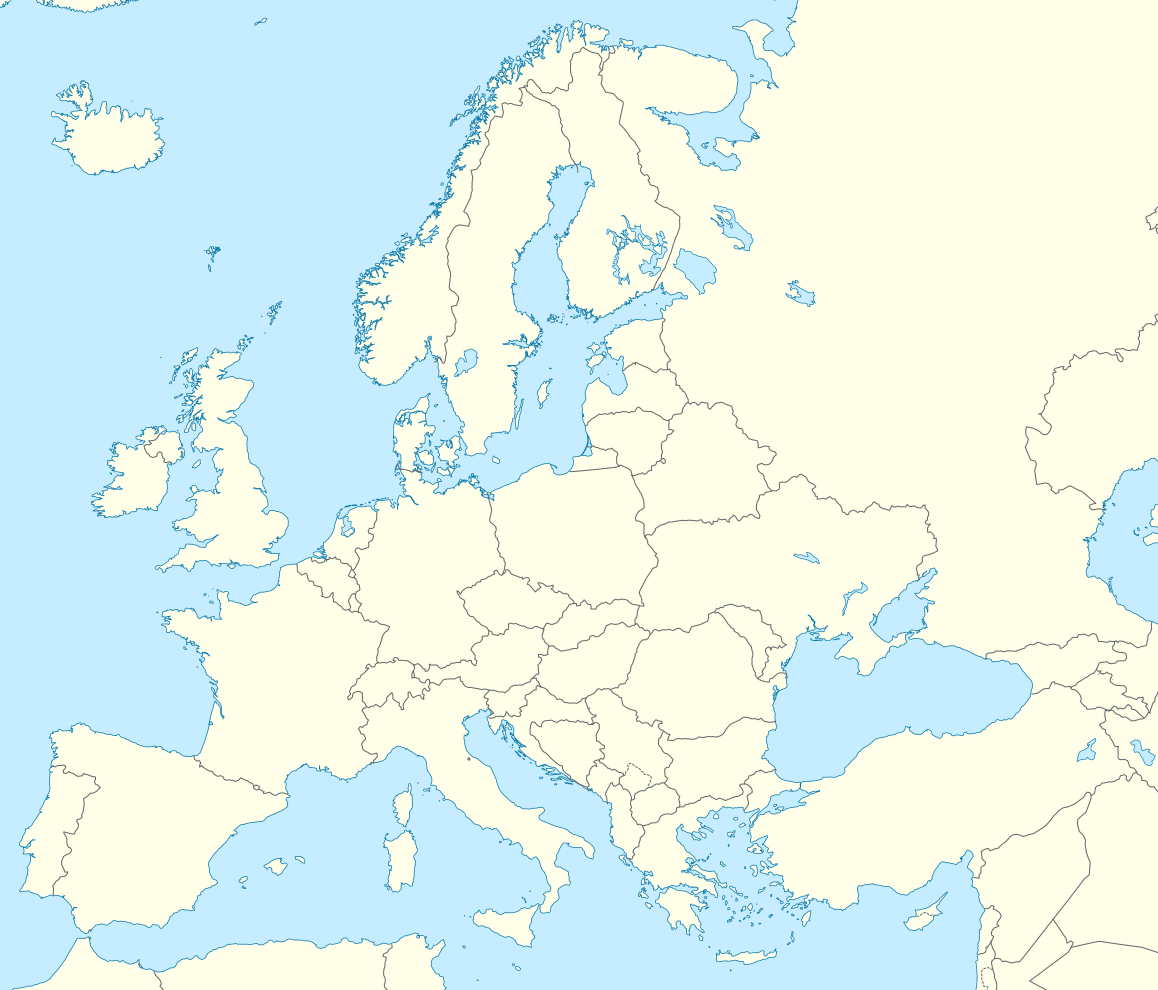

Philippopolis Shown within Europe | |

| Location | Plovdiv, Bulgaria |

|---|---|

| Region | Thrace |

| Coordinates | 42°08′36″N 24°44′56″E / 42.143333°N 24.748889°ECoordinates: 42°08′36″N 24°44′56″E / 42.143333°N 24.748889°E |

| Type | Ancient Thracian, Greek and Roman Settlement |

| Area |

Wall circuit: ca.78 ha (190 acres)[1] Occupied: 78 ha (190 acres)+ |

| History | |

| Founded | 4th century BC |

| Periods | Hellenistic Greece |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1960- |

| Website | Site |

| Part of a series on the ancient city of |

| Philippopolis |

|---|

|

| Buildings and structures |

|

Religious

Fortification

Residential

|

| Related topics |

| • History • Timeline |

Philippopolis is one of the ancient names of the city of Plovdiv by which it was known for the most of its recorded history. In 342 BC Philip II of Macedon conquered the Thracian town of Eumolpias and gave it his name. Later, Philippopolis became part of the Roman empire and capital of the Roman province Thracia. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, Philippopolis had a population of 100,000 people in the Roman period.[2]

The city was originally a Thracian settlement, later being invaded by Persians, Greeks, Celts, Romans, Goths, Huns, Bulgarians, Slav-Vikings, Crusaders and Turks.

History

The earliest signs of habitation on the territory of Philippopolis date as far back as the 6th millennium BC when the first settlements were established.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Archaeologists have discovered fine pottery[9] and objects of everyday life on Nebet Tepe from as early as the Chalcolithic, showing that at the end of the 4th millennium BC, there already was an established settlement there.[10][11][12] Thracian necropolises dating back to the 2nd-3rd millennium BC have been discovered, while the Thracian town Eumolpias was established between the 2nd and the 1st millennium BC.[13]

The town was a fort of the independent local Thracian tribe Bessi.[14] In 516 BC during the rule of Darius the Great, Thrace was included in the Persian empire.[15] In 492 BC the Persian general Mardonius subjected Thrace again, and it became nominally a vassal of Persia until 479 BC and the early rule of Xerxes I.[16] The town was included in the Odrysian kingdom (460 BC-46 AD), a Thracian tribal union. The town was conquered by Philip II of Macedon[17] and the Odrysian king was deposed in 342 BC. Ten years after the Macedonian invasion the Thracian kings started to exercise power again after the Odrysian Seuthes III had re-established their kingdom under Macedonian suzerainty as a result of a somehow successful revolt against Alexander the Great's rule resulting in neither victory, nor defeat, but stalemate.[18] The Odrysian kingdom gradually overcome the Macedonian suzerainty, while the city was destroyed by the Celts as part of the Celtic settlement of Eastern Europe, most likely in the 270s BC.[19] In 183 BC Philip V of Macedon conquered the city, but shortly after the Thracians re-conquered it.

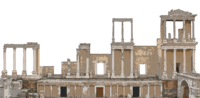

In 72 BC the city was seized by the Roman general Marcus Lucullus but was soon restored to Thracian control. In AD 46 the city was finally incorporated into the Roman Empire by emperor Claudius;[20] it served as metropolis (capital) of the province of Thrace and gained a city status in the late 1st century.[21] Trimontium was an important crossroad for the Roman Empire and was called "the largest and most beautiful of all cities" by Lucian. Although it was not the capital of the Province of Thrace, the city was the largest and most important centre in the province.[22] As such the city was the seat of the Union of Thracians.[23] In those times, the Via Militaris (or Via Diagonalis), the most important military road in the Balkans, passed through the city.[24][25] The Roman times were a period of growth and cultural excellence.[26] The ancient ruins tell a story of a vibrant, growing city with numerous public buildings, shrines, baths, theatres, a stadium and the only developed ancient water supply system in Bulgaria. The city had an advanced water system and sewerage. In 179 a second wall was built to encompass Trimontium which had already extended out of the Three hills into the valley. Many of those are still preserved and can be seen by tourists. Today only a small part of the ancient city has been excavated.[27]

In 250 AD the whole city was burned down by the Goths, led by their ruler Cniva, and many of its citizens, according to Ammianus Marcellinus numbering 100,000, died or were taken captive.[28] It took a century and hard work to recover the city. However, it was destroyed again by Attila's Huns in 441-442 and by the Goths of Teodoric Strabo in 471.[29]

Urban planning

The plan of the urban area of Philippopolis was revealed to a large extent during the archeological works in central Plovdiv carried out between 1965-85. Archeological studies and historical records confirm the presence of three archeological levels: Hellenistic, Roman and Late Roman. [30]

Hellenistic period

The initial planning and construction of Philippopolis started during Philip II's rule and continued during the reign of Alexander the Great and the Diadochi. Some authors assume that the first stage of the construction of Philippopolis ended around 500 BC.[30]

During the Hellenistic period, the former Thracian town built on the hills descended to the plain. Archeologists confirmed that the Hippodamian plan (the orthogonal urban plan of Hippodamus of Miletus) was applied to Philippopolis which was used in other ancient towns like Miletus, Ephesus, Alexandria and Olynthus.[31][30] Hellenistic Philippopolis had a network of orthogonal gravel streets which intersect each other perpendicularly. Some of the streets had sidewalks, curbs and proper slope to accommodate rain water drainage. The intersecting streets formed the rectangular city blocks (insula) with residential and public buildings.[30] A great number of public structures were built in Philippopolis such as theatre, stadium, agora, temples, thermae. The unit of measure used in the first period of construction in Philippopolis was the Attica (Athens) step (296 mm).

Despite the unstable political and economic environment from the 4th century BC to the 1st century BC, large-scale urban planning and complex construction techniques were implemented in Philippopolis. The initial urban planning model of the town adopted in the Hellenistic period was strictly followed and developed after the city became part of the Roman empire.

Roman period

The second building period in Philippopolis refers to the period after the town became part of the Roman empire in 46 AD and capital of the Roman province Thracia. Extensive renovation and large-scale construction took place during that period in order to meet the growing needs of the population. The Romans continued the legacy left by the Greek architects of Philippopolis. The unit of measure used by the Romans (the Roman foot - 296 mm) coincided almost entirely with the Attica step used in the Hellenistic period thus allowing them to easily follow the initial urban planning model of the town without making significant alterations.

In the Roman era the built up area of Philippopolis totaled 50 ha (120 acres). It included around 150 insulae each with a width of 1 actus (35.5 m) and length of 2 actus (71 m).[30] The existing street network was renovated and expanded with water supply and sewer system beneath it. The area of the road network amounted to 100,000 sq.m.[30] The streets were paved with large granite slabs. The length of a normal street was 15 Roman feet (4.4 m) while the length of the main streets reached 30 Roman feet (8.9 m).[30] Some of the important public buildings from the Hellenistic period like the theatre, the stadium, the agora were rebuilt and expanded. A typical characteristic of the buildings in Roman Philippopolis was their large scale and lavish decoration which expressed the greatness and influence of the Roman Empire.

References

- ↑ Марк Аврелий и Филипопол

- ↑ Елена Кесякова; Александър Пижев; Стефан Шивачев; Недялка Петрова (1999). Книга за Пловдив (in Bulgarian). Пловдив: Издателство „Полиграф“. pp. 47–48. ISBN 954-9529-27-4.

- ↑ "Archaeologists Explore Ancient Roman Forum of Philippopolis". Popular Archaeology. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ „Philippopolis Album“, Kesyakova Elena, Raytchev Dimitar, Hermes, Sofia, 2012, ISBN 978-954-26-1117-2

- ↑ History (Plovdiv) Official website in English

- ↑ Райчевски, Георги (2002). Пловдивска енциклопедия. Пловдив: Издателство ИМН. p. 341. ISBN 978-954-491-553-7.

- ↑ Кесякова, Елена; Александър Пижев, Стефан Шивачев, Недялка Петрова (1999). Книга за Пловдив. Пловдив: Издателство „Полиграф“. pp. 17–19. ISBN 954-9529-27-4. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Darik

- ↑ "Plovdiv: New ventures for Europe's oldest inhabited city". The Courier. January–February 2010.

- ↑ Детев П., Известия на музейте в Южна България т. 1 (Bulletin des musees de la Bulgarie du sud), 1975г., с.27, ISSN 0204-4072

- ↑ Детев, П. Разкопки на Небет тепе в Пловдив, ГПАМ, 5, 1963, pp. 27–30.

- ↑ Ботушарова, Л. Стратиграфски проучвания на Небет тепе, ГПАМ, 5, 1963, pp. 66–70.

- ↑ Archeological investigation of Plovdiv European Capital of Culture for 2019 (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ Елена Кесякова; Александър Пижев; Стефан Шивачев; Недялка Петрова (1999). Книга за Пловдив (in Bulgarian). Пловдив: Издателство „Полиграф“. pp. 20–21. ISBN 954-9529-27-4.

- ↑ The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth,ISBN 0-19-860641-9," page 1515, "The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- ↑ The orders, medals, and history of the Kingdom of Bulgaria by Dimitri Romanoff, p. 9

- ↑ История на България, Том 1, Издателство на БАН, София, 1979, p. 206.

- ↑ Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great by A. B. Bosworth s,"page 12,"Cambridge University Pres"

- ↑ Bulgaria. University of Indiana. 1979. p. 4.

- ↑ Dimitrov, B. (2002). The Bulgarians – the first Europeans (in Bulgarian). Sofia: University press "St Climent of Ohrid". p. 17. ISBN 954-07-1757-4.

- ↑ История на България, Том 1, Издателство на БАН, София, 1979, p. 307.

- ↑ Lenk, B. – RE, 6 A, 1936 col. 454 sq.

- ↑ Римски и ранновизантийски градове в България, p. 183

- ↑ "Cultural Corridors of South East Europe/Diagonal Road". Association for Cultural Tourism.

- ↑ Николов, Д. Нови данни за пътя Филипопол-Ескус, София, 1958, p. 285

- ↑ Dimitrov, B. (2002). The Bulgarians – the first Europeans (in Bulgarian). Sofia: University press "St Climent of Ohrid". pp. 18–19. ISBN 954-07-1757-4.

- ↑ PlovdivCity.net, посетен на 10 ноември 2007 г.

- ↑ Елена Кесякова; Александър Пижев; Стефан Шивачев; Недялка Петрова (1999). Книга за Пловдив (in Bulgarian). Пловдив: Издателство „Полиграф“. pp. 47–48. ISBN 954-9529-27-4.

- ↑ Roman Plovdiv: History

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 „Древният Филипопол“, arch. М. Mateev, „Жанет 45“, Plovdiv, 1999, ISBN 978-954-491-821-7

- ↑ Trakia, V.Velkov, Plovdiv, 1976