Pitfour estate

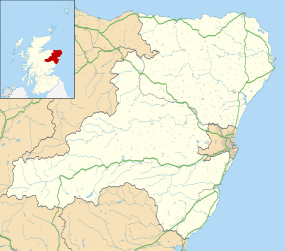

The Pitfour estate, in the Buchan area of north-east Scotland, was an ancient barony encompassing most of the extensive Longside Parish, stretching from St Fergus to New Pitsligo. It was purchased in 1700 by James Ferguson of Badifurrow, who became the first Laird of Pitfour.

The estate was substantially renovated by Ferguson and the following two generations of his family. At the height of its development in the 18th and 19th centuries the 50-square-mile (130 km2) property had several extravagant features including a two-mile racecourse, an artificial lake and an observatory. The original mansion house was extended before being rebuilt. The surrounding parklands were landscaped, major renovations were undertaken, and follies such as a small replica Temple of Theseus were constructed, in which George Ferguson, the fifth laird, was thought to keep alligators in a cold bath.

The first three lairds transformed the estate into a valuable asset. Lord Pitfour, the second laird, purchased additional lands including Deer Abbey and Inverugie Castle. Pitfour's son, James Ferguson, who became the third laird, continued to improve and expand the estate by adding the lake and bridges, and establishing planned villages. The third laird died a bachelor with no children, so the estate passed to the elderly George Ferguson, who was only in possession of the property for a few months. George was already a wealthy man, owning lands in Trinidad and Tobago, but despite not directly improving the Pitfour estate he added considerable value to the inheritance passed to his illegitimate son. The extravagant lifestyles of the fifth and sixth lairds led to the sequestration of the estate, which was sold off piecemeal to pay their debts.

What remained of the estate was sold after the First World War. The mansion house was demolished in about 1926, and its stone used to build council houses in Aberdeen. In more recent times some of the remaining buildings, including the temple, the bridges and the stables, have been classified as at high risk by Historic Scotland because their condition has become poor. The chapel was fully renovated and converted to a private residence in 2003; the observatory was purchased and restored by Banff & Buchan District Council (now Aberdeenshire Council) and can be accessed by the public. The racecourse has been forested since 1926, and the lake is used by members of a private fishing club.

Early history

The Pitfour estate in Mintlaw extended from St Fergus to New Pitsligo and encompassed most of the extensive Longside Parish.[1][2] The meaning of Pitfour is given in the 1895 records of the Clan Fergusson as "cold croft",[3] but the historian John Milne[4] breaks the name into two parts and indicates the meaning as Pit being place and feoir or feur being grass.[5] The Pitfour estate is shown on old maps as Petfouir or Petfour.[6] It was formerly one of Scotland's largest and best-appointed estates and was referred to as "The Blenheim of Buchan", "The Blenheim of the North" and "The Ascot of the North" by the architectural historian Charles McKean.[7][8][9]

Scant early records exist of the lands but Alexander Stewart (Alexandro Senescalli), the natural son of King Robert II of Scotland, was given the Pitfour lands together with those of Lunan by his father in 1383.[10][11] However, writing in 1887 Cadenhead states the lands were sold to Stewart by Ricardus Mouet, also known as Richard Lownan.[12] During the next three centuries the lands had several different owners. Transactions show it passed to a burgess of Aberdeen in 1477 from Egidia Stewart; Walter Innes of Invermarkie gained feudal superiority to all Pitfour lands in 1493; and in 1506 the land was purchased by Thomas Innes, who died the following year. His son, John, inherited the property. It remained in the possession of the Innes family until at least 1581, when it was owned by James Innes and his wife Agnes Urquhart.[13] Between 1581 and 1667 the lands were bought by George Morrison.[6] His son William inherited the property in 1700, and immediately sold the estate to James Ferguson, who became the first Laird of Pitfour.[6]

The lands purchased by Ferguson were recorded in 1667 in a charter granted by Charles II and were stated as encompassing "the lands and Barony of Toux and Pitfour in the Parish of Old Deer and Sheriffdom of Aberdeen including the towns and lands of Mintlaw, Longmuir, Dumpston in the Parish of Longside, and County of Aberdeen." Several other lands, including "the Barony of Aden with the Tower, Fortaliss, Mains and Manor Place therof and pertinents of the same called Fortry, Rora Mill thereof, Croft Brewerie, Inverquhomrie and Yockieshill" were individually listed.[14] State papers from the reign of Queen Anne in the 18th century record the lands in favour of James Ferguson.[15]

Lairds and subsequent development

1st laird

James Ferguson—known as the Sheriff, reflecting the post he held, recognised by the Society of Advocates—bought the Pitfour estate after selling the lands of Badifurrow.[16] He had inherited Badifurrow after demanding that his uncle Robert Ferguson should appear in court if he wished to contest the inheritance. Robert, nicknamed the Plotter, was in hiding to avoid charges of treachery,[17] and after his non-appearance in court James Ferguson's inheritance was confirmed in mid-June 1700.[6] At that time the estate contained only a small country house.[18][19]

2nd laird

James was laird until his death in 1734, after which the estate passed to his eldest son, also called James, who was born at Pitfour soon after it was purchased.[20] A solicitor like his father, he was promoted to the bench in 1764 and became Lord Pitfour. He continued to expand and improve the estate until his death in 1777,[7] and set up the planned village of Fetterangus in 1752.[21]

Lord Pitfour purchased the lands of the last Earl Marischal, George Keith, which were adjacent to Pitfour, in 1766. They were considered the Earl Marischal's most significant property[lower-alpha 1] and had been forfeited when the Earl Marischal fell out of favour. He had bought it back from the York Buildings Company for £31,000, but Pitfour only paid £15,000 for it. The 8,000 acres (32 square kilometres) of land included Deer Abbey and Inverugie Castle, but consisted predominantly of peat bogs, woods and uncultivated land. This addition made the Pitfour estate the largest in the area, at more than 30,000 acres (120 square kilometres) stretching from Buchanhaven to Maud along the course of the River Ugie.[19][23][24][25]

3rd laird

The third laird, also named James, inherited the estate in 1777; he was usually referred to as the Member to differentiate him from previous generations. Like his forebears, he was an advocate but also became a Member of Parliament.[26] He too continued to expand and improve the estate; he constructed a lake and a canal, and built the new mansion.[27] He also expanded and altered Longside at the start of the 1800s, founded Mintlaw in 1813, assisted in the extension of New Deer and extended Buchanhaven.[21]

The Member died unmarried, childless and intestate in 1820. In normal circumstances his brother Patrick would have been his heir, but he died in battle in October 1780.[28]

4th laird

In 1820 the estate was inherited by the Member's younger brother, George Ferguson, who was by then in his seventies. He was known as the Governor, reflecting his appointment as Lieutenant Governor of Tobago. He was laird from September 1820, but died in December that year. The Governor had spent most of his life in Trinidad and Tobago, where he was a principal landowner, and had inherited the Castara Estate on Tobago from Patrick. George was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Tobago in 1779, and after a battle with the French in 1781 surrendered the island to the French on 2 June. The Governor returned to Britain, although the terms of the surrender meant he still owned the Castara estate and all the slaves who worked on it. George had illegitimate children with an unknown woman. He continued to buy estates in the Caribbean and returned there in 1793, staying until 1810.[29]

5th laird

The estate started to deteriorate after it was inherited by the Governor's illegitimate son George Ferguson, known as the Admiral because of his naval career. He was already heavily in debt when he became the fifth laird in 1821, but he still enjoyed a lavish lifestyle and undertook much extravagant construction on the estate, including the erection of follies. To cover his substantial gambling debts, he began to sell parcels of estate land, and upon inheriting Pitfour he began selling furniture, books, farm equipment and other items, realising more than £9,000.[30]

6th laird

After the Admiral's death in March 1867, the estate passed to his son, George Arthur Ferguson, the sixth and final laird. He served in the Grenadier Guards and eventually became a captain. He married Nina Maria Hood, the eldest daughter of Alexander Nelson Hood, 1st Viscount Bridport, in February 1861.[31][32] Later that year Captain Ferguson was posted to Canada, where he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and where his first two sons, Arthur and Francis William, were born. His eldest son, Arthur, became Inspector of Constabulary for Scotland. Returning to Britain in 1864, the family had a nomadic lifestyle, but the sixth laird and his wife were extravagant and habitual gamblers. In June 1909, a trust deed was registered, and what remained of the estate was put on the market.[33] After large parts of the land had been sold under the ownership of the sixth laird the estate was listed by Bateman in 1883 as being just over 23,000 acres (93 square kilometres) with an income of £19,938;[34] at the height of its development the estate had occupied 50 square miles (130 square kilometres), and was valued at £30 million.[35]

The last laird died in 1924 and is buried in Luton.[36]

Following its 20th-century decline the estate changed hands several times until local farmer Hamish Watson purchased it in December 2010.[37][38] The local historian Alex Buchan summed up the demise of the estate: "They thought the estate was here to provide them with money, to gamble, to travel, to simply fritter away and very quickly, within a couple of decades, they had wasted the whole lot." He added, "Eccentricity amounted to just squandering money."[35]

Mansion house

The original small country house was first altered during the early 18th century. In 1809 the Sheriff's grandson James Ferguson, the third laird, employed the architect John Smith to design new accommodation. The resulting three-storey house, 98 feet (30 metres) square and 33 feet (10 metres) high, is reputed to have had 365 windows. When the fourth laird, George (the Governor), died in 1820, the estate was worth £300,000 with almost £35,000 of moveable assets.[39] George Ferguson, the fifth laird (the Admiral) added a large, glazed gallery when he inherited the house.[27] The Admiral had a lavish lifestyle and despite having a healthy income incurred heavy debts.[40]

When the Admiral died after 46 years of managing the estate it was mortgaged for £250,000, despite the sale of a number of the lands originally included in it.[41] The house fell into disrepair under the ownership of George Arthur, the sixth and final laird, who had inherited his father's lifestyle.[40] The entire estate was put on the market in September 1909 but remained unsold until after the First World War; the house and what remained of the estate were finally purchased by a speculator, Edgar Fairweather, from London in 1926.[36] Fairweather bought several other Scottish estates, including those nearby at Auchmeddan and Strichen; he habitually reduced the estates into smaller holdings that he then sold on or rented out.[42][43] The house was sold to an Aberdeen building company and was demolished sometime between 1927 and 1930.[36][44] After demolition, the mansion's veranda was installed at the front of Kinloch Farmhouse in St Fergus. Other remains from the mansion have been discovered at the farmhouse, including a crest above the conservatory door and tiles inscribed with the Ferguson of Pitfour family crest.[45][46] The stone from the mansion was transported to Aberdeen and used in the construction of council houses.[47]

Chapels

The Fergusons were Episcopalian, and in 1766, the second laird, Lord Pitfour had a small Qualified Chapel built on the estate at Waulkmill. It was a large, plain building that could accommodate up to 500 people.[48] Saplinbrae, a house that was initially used as a coaching inn after it was built under instruction from Lord Pitfour in 1756, was used as the minister's manse for the first chapel.[19][49][50]

A more modern chapel was built in 1850 after the Admiral had an argument with the Reverend Arthur Ranken, the minister at Old Deer.[51] This was a small, private chapel for the use of the Pitfour estate.[52] It was built in the Gothic style from rubble but was recast in 1871. A 60-foot (18-metre) tower with a battlemented top is at its western end. The chapel fell into disrepair, and by the 1980s it was a roofless ruin.[53][54]

In 1990 Historic Scotland said that Kinloch Farmhouse, in St Fergus featured a bench and chair salvaged from the Pitfour Chapel.[46] In 2003, the second chapel was renovated and converted to a private residence.[55] The chapel restoration won a "Highly commended" award for craftsmanship from Aberdeenshire Council in 2010; the council said the craftsmanship "allowed for the retention of the ecclesiastical spirit and integrity to remain prevalent both internally and externally." It was also "Highly Commended" in the conservation category.[56]

Stables and riding school

The stables were built in 1820, during the early part of the Admiral's ownership of the estate, based on a design by John Smith;[57] the buildings are sited to the rear of the mansion house.[58] Built in a horseshoe-shape, neo-classical design, the two-storey building was constructed in pinned rubble with granite dressings; grey granite was used for the parapet and quoins. The main buildings were originally harled. A corrugated asbestos hipped roof was at some point substituted for the original slate roof. It features a columned rotunda above a timber clock tower, which has a finial and domed copper roof. The pedimented centrepiece of the symmetrical front elevation is a segmental arch and has three panels set back between columns. Each side is bordered by wings of three bays with single-bay pavilions.[44]

The stables are connected to an adjoining two-storey house.[44] They provided accommodation for ten horses and included four loose boxes, a harness room and a coachman's house; six bedrooms above were for servants. Two coach houses were later used as garages.[59] The stables building was marketed in 1997 for approximately £70,000.[57] Charles McKean describes the stables as "straddling the skyline like a palace".[45] The stables are listed by Historic Scotland as being at very high risk,[44] and were described in 1997 sale literature as unused and dilapidated.[57]

An indoor riding school slightly to the north-west of the stables measured 98 feet (30 metres) by 49 feet (15 metres). It was used to entertain guests when the facilities at the mansion house were not large enough. More than two hundred local farmers and other landowners celebrated the wedding of George Arthur, the sixth laird, in the riding school in 1861. In 1883 it was again used to entertain; on that occasion it was decorated with flags and Chinese lanterns, and pine flooring was laid. Later, it was used as indoor tennis courts before being demolished.[59]

Canal and lake

James Ferguson, the third laird, owned the estate during the Industrial Revolution in Britain. He began work on a canal between Pitfour and Peterhead in 1797, despite fierce opposition from adjoining landowners. The canal was proposed to cover about ten miles following the course of the River Ugie.[60] Pitfour's canal is sometimes called the St Fergus and River Ugie Canal.[61] Ferguson had thought about building the canal since 1793, but it was never completed because of "difficulties in effecting the necessary arrangements with neighbouring heritors."[61] Objections were raised by the Merchant Maiden Hospital, which owned the land on the south side of the Ugie. Despite being advised to take out an interdict to prevent the work, in January 1797 the hospital thought its case was not strong enough. The hospital applied for an interdict four months later however, when two miles (3.2 km) of the canal had been dug to the point where the north and south Ugie joined; it was granted in July 1797.[62]

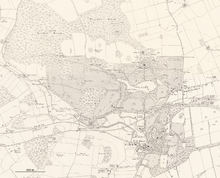

A few years after starting work on the canal, Ferguson had a lake built on flat land to the front of the mansion house. The landscape gardener William S. Gilpin was carrying out work on the adjacent Strichen estate at about the same time, and it is assumed he helped with the work at Pitfour. The lake extends to almost 50 acres (20 hectares) and is 174 feet (53 metres) above sea level.[63] Designed in the same style as the lake in Windsor Great Park, the lake was stocked with trout, both rainbow and brown; there were three bridges and four islands.[64] The siting of the lake meant the driveway had to be moved, and ornate bridges were constructed to cross the water. Built from granite, the northern bridge has three arches with ashlar starlings, the southern bridge has a single arch and the third, smaller bridge crosses a large stream that drains into the lake.[65]

The neighbouring Russell family of Aden were concerned their land would be flooded when the lake was built, and their animosity was fully demonstrated when a bridge had to be jointly constructed by the two landowners over the River Ugie. It was wide enough for carriages on the Pitfour side but too narrow on the Russell's half.[66]

Theseus temple

Alongside the lake was a six-bay Greek Doric temple, a small replica styled after the Temple of Theseus. Its exact date of construction is unknown; it may have been built during the time of James Ferguson, the third laird, or under the instruction of George Ferguson, the fifth laird.[67] The local historian Alex Buchan attributes it to James, the third laird;[65] according to Historic Scotland, it was built "probably circa 1835".[68] Like the mansion house, the temple is credited to the architect John Smith.[68] Measuring 8 metres (26 ft) by 16 metres (52 ft), it has six columns at both ends and thirteen columns down each side. It had a flat roof with an ornate wooden entablature and contained a cold-water bath in which George, the fifth laird was believed to have kept alligators.[35][67][69][70] As of 2013 the temple is in a ruinous state; it has been held up by scaffolding since 1992 and is listed by Historic Scotland as being in critical condition.[68]

Racecourse and observatory

George Ferguson (the Admiral) had a racecourse about 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometres) long and 52 feet (16 metres) wide built near White Cow Woods, an area which is quite flat.[59] This led to the estate being called the "Ascot of the North".[35]

In 1845 the Admiral had an observatory built, again designed by the architect John Smith. It is an octagonal tower with a crenellated parapet and is symmetrical in design. The observatory stands at the top of a hill 396 feet (121 m) above sea level. The tower is 50 feet (15 m) high and is more than half a mile (1 kilometre) from the racecourse. It has three storeys with square windows on the upper floor, and was fully renovated by Banff & Buchan District Council (now Aberdeenshire Council) in 1983.[59][71][72]

Twentieth century

Sales of country estates became common around the 1920s. The annual tax payable had spiralled and was twenty times greater than in 1870 resulting in the break-up of many larger land-holdings. Pitfour was no exception and the dispersal of the estate continued piecemeal after the sequestration of George Arthur, the sixth laird.[73] The main estate policies[lower-alpha 2] including the lake and other land were purchased by Bernard Drake in November 1926 when he bought Saplinbrae, the former minister's house. Drake was a partner in the electrical engineering company, Drake and Gorham.[74][75]

Sixty years later, in 1986 the BBC Domesday Project does not give any ownership details but indicates many of the buildings are in poor condition. Other surviving structures are used for storage by a farmer who also "manages the land".[76]

Recent times

At the end of 2012 Aberdeenshire Council gave the go-ahead for the present owner's planned restoration work on the temple and bridges, which he hoped would enhance existing facilities at nearby Drinnies Wood surrounding the Observatory, White Cow Woods and Aden Country Park.[38][77][lower-alpha 3] The lake is used regularly by local fishermen, and a fishing club with about 120 members was established in 2011.[80] The rest of the estate is seldom used by local residents, many of whom are completely unaware of it.[38]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Inverugie Castle was the main residence of the Earl Marischal after Dunnottar Castle was used to house rebels but became ruinous after being forfeited in 1715.[22]

- ↑ The definition of policies as used in Scots land terminology given in the OED is: "The enclosed (and often ornamental) grounds, park, or demesne land surrounding a large country house."

- ↑ Large areas of the former Pitfour lands are incorporated into the Forest of Deer; this includes the site of the Observatory within Drinnies Wood and the Racecourse. The oldest parts of the woods were established in 1926 when the Forestry Commission purchased 1,200 acres (4.9 square kilometres) of Pitfour land.[78][79]

Citations

- ↑ "Pitfour estate". Mintlaw Community Council. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Hay & May (2000), p. 210

- ↑ Ferguson & Fergusson (1895), p. 573

- ↑ "John Milne Ref:MS 2085". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ↑ Milne (1912), p. 261

- 1 2 3 4 Buchan (2008), p. 4

- 1 2 "Wonderful insight into the history of Pitfour estate". Buchan Observer. Peterhead. November 25, 2008. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ McKean (1990), pp. 91–92

- ↑ "Obituary: Prof Charles McKean, architectural historian". The Scotsman. 1 October 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ↑ Ferguson (1913), p. 34

- ↑ Fittis (1878), p. 235

- ↑ Cadenhead (1887), p. 31

- ↑ Ferguson (1913), pp. 34–35

- ↑ Hay & May (2000), p. 212

- ↑ Mahaffy (editor), R. P. (1916). "Anne: Table IX. Scottish Warrants and Commissions". Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Anne, 1702-3. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 13 February 2013. (subscription required)

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 6

- ↑ Davidson (1878), p. 376

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 71

- 1 2 3 Wilson Smith, J. (June 1949). "How a Ferguson first came to Pitfour". Buchan Observer. Peterhead.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 5

- 1 2 Buchan (2008), pp. 86–87

- ↑ Buchan Field Club (1908), p. 76

- ↑ Ferguson (1913), p. 22

- ↑ Hay & May (2000), pp. 211–212

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 82

- ↑ Foster (1882), p. 133

- 1 2 Buchan (2008), p. 76

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 22

- ↑ Buchan (2008), pp. 33–38

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 42

- ↑ "Auction archive". Dix Noonan Webb. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 48

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 52

- ↑ Bateman (1883), p. 161

- 1 2 3 4 "New owner hopes to restore estate to former glory". STV. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 Buchan (2008), p. 53

- ↑ "Buchan area committee report, section 2.5" (PDF). Aberdeenshire Council. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Buchan man hopes to up hidden estate". Buchan Observer. January 5, 2012. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 39

- 1 2 Buchan (2008), p. 49

- ↑ Hay & May (2000), p. 213

- ↑ Buchan (2008), pp. 53–54

- ↑ Lockhart, Douglas G. (2001), "Lotted Lands and Planned Villages in North-East Scotland", The Agricultural History Review, British Agricultural History Society, 49 (1): 34, JSTOR 40275687

- 1 2 3 4 "Pitfour House Stables, Ref No:1191". Buildings at risk register. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- 1 2 McKean (1990), p. 92

- 1 2 "Kinloch Farmhouse (Ref No:18976)". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 124

- ↑ Wilson Smith, J. (June 1949). "How the estate of St Fergus was added to the broad lands of Pitfour". Buchan Observer. Peterhead.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 75

- ↑ "Saplinbrae (Ref No:16061)". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ Bertie (2000), p. 533

- ↑ "Pitfour House chapel". Scottish Church Heritage Research. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Chapel, Pitfour". SCRAN. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013. Subscription or UK public library membership required

- ↑ "Pitfour House estate chapel Ref No:116850". Canmore. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ "APP/2003/1705". Aberdeenshire Council. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ "Design Awards 2010" (PDF). Aberdeenshire Council. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Shields, Jenny (23 May 1997). "National Treasures Worth Rescuing from the Rubble". Daily Mail. Retrieved 1 April 2013. Subscription or UK public library membership required

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 80

- 1 2 3 4 Buchan (2008), p. 81

- ↑ Buchan (2008), pp. 95–96

- 1 2 Graham (1967), p. 176

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 96

- ↑ Buchan (2008), pp. 76–77

- ↑ Buchan, Jamie (30 September 2008). "Historic £850,000 estate angling for a buyer". Press & Journal. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- 1 2 Buchan (2008), p. 77

- ↑ Smith (1988), p. 186

- 1 2 "Pitfour House, Temple of Theseus". Canmore. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Pitfour House: Temple of Theseus, Pitfour House Estate". Buildings at Risk register. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 78

- ↑ McKean (1990), p. 93

- ↑ "NJ94NE0050 – Drinnie's Wood". Aberdeenshire Council. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ "Sites of interest". Aden Country Park. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ Buchan (2008), p. 123

- ↑ "Sir Harry Hope's purchase". The Scotsman. 10 November 1926.(subscription required)

- ↑ "Bernard Drake" (PDF). The Heritage Group. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ "Pitfour estate (D-block GB-396000-849000)". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ "Pitfour Estate restoration plans given go ahead". Buchan Observer. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Dey (1976), p. 68

- ↑ "Buchan Forestry". Aberdeen Journal (1136). 28 July 1926. p. 6 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "About us". Pitfour Flyfishing Club. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

Bibliography

- Bateman, John (1883), The Great Landowners of Great Britain, Harrison

- Bertie, David (2000), Scottish Episcopal Clergy, 1689–2000, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-567-08746-1

- Buchan, Alex R. (2008), Pitfour: "The Blenheim of the North", Buchan Field Club, ISBN 978-0-9512736-4-7

- Cadenhead, George (1887), The family of Cadenhead, J. & J. P. Edmond and Spark

- Davidson, John (1878), Inverurie and the Earldom of the Garioch. A Topographical and Historical Account of the Garioch from the Earliest Times to the Revolution Settlement., Brown & Company

- Dey, George (1976), "Royal Deeside and Forests to the north", in Edlin, Herbert L., Forests of north-east Scotland, H.M. Stationery Office, ISBN 978-0-11-491433-2

- Ferguson, James (1913), The Old Baronies of Buchan, P. Scrogie, "Buchan Observer" Works

- Ferguson, James; Fergusson, Robert Menzies (1895), Records of the clan and name of Fergusson, Ferguson and Fergus, Edinburgh: D. Douglas

- Fittis, Robert Scott (1878), Sketches of the olden times in Perthshire, Perth, p. 235

- Foster, Joseph (1882), Members of Parliament, Scotland, Hazell, Watson and Viney

- Graham, Angus (1967), "Two Canals in Aberdeenshire" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 100: 176, archived from the original on 26 May 2013, retrieved 4 December 2012

- Hay, G. M.; May, V. & S. (2000), Longside: A Parish and Its People, Longside Parish Church, ISBN 978-0-9539586-0-3

- McKean, Charles (1990), Banff & Buchan, Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, ISBN 978-1-85158-231-0

- Milne, John (1912), Celtic Place-names in Aberdeenshire, Aberdeen Daily Journal

- Smith, Robert (1988), Discovering Aberdeenshire, J. Donald, ISBN 978-0-85976-229-8

- Buchan Field Club (1908), Transactions of the Buchan Field Club, 10, The Club

Coordinates: 57°31′59″N 2°2′7″W / 57.53306°N 2.03528°W