Posterior cruciate ligament injury

The function of the PCL is to prevent the femur from sliding off the anterior edge of the tibia and to prevent the tibia from displacing posterior to the femur. Common causes of PCL injuries are direct blows to the flexed knee, such as the knee hitting the dashboard in a car accident or falling hard on the knee, both instances displacing the tibia posterior to the femur.[1]

The posterior drawer test is one of the tests used by doctors and physiotherapists to detect injury to the PCL.

Surgery to repair the posterior cruciate ligament is controversial due to its placement and technical difficulty.[2]

An additional test of posterior cruciate ligament injury is the posterior sag test, where, in contrast to the drawer test, no active force is applied. Rather, the person lies supine with the leg held by another person so that the hip is flexed to 90 degrees and the knee 90 degrees.[3] The main parameter in this test is step-off, which is the shortest distance from the femur to a hypothetical line that tangents the surface of the tibia from the tibial tuberosity and upwards. Normally, the step-off is approximately 1 cm, but is decreased (Grade I) or even absent (Grade II) or inverse (Grade III) in injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament.[4]

Patients who are suspected to have a posterior cruciate ligament injury should always be evaluated for other knee injuries that often occur in combination with an PCL injuries. These include cartilage/meniscus injuries, bone bruises, ACL tears, fractures, posterolateral injuries and collateral ligament injuries.

How PCL injury occurs

Related anatomy

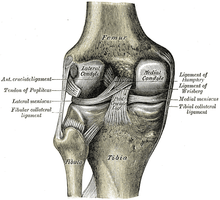

To understand how posterior cruciate ligament injury can occur, one must consider the anatomical and physiological properties of the PCL. The PCL is located within the knee joint where it stabilizes the articulating bones, particularly the femur and the tibia, during movement. It originates from the lateral edge of the medial femoral condyle and the roof of the intercondyle notch[5] then stretches, at a posterior and lateral angle, toward the posterior of the tibia just below its articular surface.[6][7][8][9]

Related physiological features

Although each PCL is a unified unit, they are described as separate anterolateral and posteromedial sections based off where each section's attachment site and function.[10] During knee joint movement, the PCL rotates [9][11] such that the anterolateral section stretches in knee flexion but not in knee extension and the posteromedial bundle stretches in extension rather than flexion.[7][12]

The types of mechanisms that lead to PCL injury

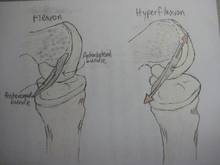

In this position, the PCL functions to prevent movement of the tibia in the posterior direction [7][13] and to prevent the tilting or shifting of the patella.[14] However, the respective laxity of the two sections makes the PCL susceptible to injury during hyperflexion, hyperextension,[15] and in a mechanism known as a dashboard injury.[9] Because ligaments are viscoelastic (p. 50 [16]) they can handle higher amounts of stress only when the load is increased slowly (p. 30 [16]). When hyperflexion and hyperextension occur suddenly in combination with this viscoelastic behavior, the PCL deforms or tears.[15] In the third and most common mechanism, the dashboard injury mechanism, the knee experiences impact in a posterior direction during knee flexion toward the space above the tibia.[10][15] These mechanisms occur in excessive external tibial rotation and during falls that induce a combination of extension and adduction of the tibia, which is referred to as varus-extension stress,[10] or that occur while the knee is flexed.[15]

Prevention

Knee injury

Knee injuries are very common among athletes as well as regular active people and can always be prevented. Ligament tears account for more than forty percent of knee injuries and the posterior cruciate ligament is considered one of the less common injuries.[17] Although it is less common, there are still important measures that can be taken in order to prevent this type of knee injury. Maintaining proper exercise and sport technique is crucial for injury prevention, which include not exceeding the body or not going over the proper range of motion of the knee, properly warming up and cooling down[18]

Quadriceps and hamstring ratio

Another important aspect of maintaining an injury free knee is having strong quadriceps and hamstring muscles because they help stabilize the knee. A low hamstring to quadriceps ratio is associated with knee injury and should be about eighty percent.[19] Some exercises to strengthen the quadriceps and hamstring muscles include leg curls, leg lifts, prone knee flexion with resistance band and knee extensions. Some stretches to help prevent injury to the posterior cruciate ligament include stretching of the hamstring muscles by extending the legs, toes pointing up, leaning forward until the stretch is felt and holding for a few seconds.

Exercises and stretches

In addition, balancing exercises have also been adopted because it has been proven that people with poor balance have more knee injuries than those with good balance. Wobble boards and Bosu balls are very common pieces of equipment used to balance and help prevent knee injuries as long as they are being used with trained personnel.[20] Another possible preventive measure is wearing knee straps to help stabilize the knee and protect it from injury, especially during demanding sports such as football.[21]

Treatment

It is possible for the PCL to heal on its own. Surgery is usually required in complete tears of the ligament. Surgery usually takes place after a few weeks, in order to allow swelling to decrease and regular motion to return to the knee. A procedure called ligament reconstruction is used to replace the torn PCL with a new ligament, which is usually a graft taken from the hamstring or Achilles tendon from a host cadaver. An arthroscope allows a complete evaluation of the entire knee joint, including the knee cap (patella), the cartilage surfaces, the meniscus, the ligaments (ACL & PCL), and the joint lining. Then, the new ligament is attached to the bone of the thigh and lower leg with screws to hold it in place.[22]

Rehabilitation

Grades of injury

The posterior cruciate ligament is located within the knee. Ligaments are sturdy bands of tissues that connect bones. Similar to the anterior cruciate ligament, the PCL connects the femur to the tibia. There are four different grades of classification in which medical doctor’s classify a PCL injury: Grade I, the PCL has a slight tear. Grade II, the PCL ligament is minimally torn and becomes loose. Grade III, the PCL is torn completely and the knee can now be categorized as unstable. Grade IV, the ligament is damaged along with another ligament housed in the knee (i.e. ACL). With these grades of PCL injuries, there are different treatments available for such injuries.

Rehabilitation options

It is possible for the PCL to heal on its own without surgery when it is in Grades I and II. PCL injuries that are diagnosed in these categories can have their recovery times reduced by performing certain rehabilitative exercises. Fernandez and Pugh(2012) found that following a PCL grade II diagnosis, a multimodal treatment that spanned over the course of 8 weeks consisting of chiropractic lumbopelvic manipulation, physiotherapy, and implementing an exercise program that emphasized in eccentric muscle contraction (lunges, 1-leg squats, and trunk stabilization) which proved to be an effective way to recover from the PCL injury.[23] For Grades III and IV, operative surgery is recommended or is usually needed. Grafts is the method when addressing PCL injuries that are in need of operative surgery. With grafts, there are different methods such as the tibial inlay or tunnel method.[24]

Epidemiology

Percentage of PCL to other knee injuries

According to[25] the posterior cruciate ligament injuries only account for 1.5 percent of all knee injuries (figure 2). If it is a single injury to the posterior cruciate ligament that requires surgery only accounted for 1.1 percent compared to all other cruciate surgeries but when there was multiple injuries to the knee the posterior cruciate ligament accounted for 1.2 percent of injuries.

National statistics

In 2010 national statistics was done by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for posterior cruciate ligaments injuries. They found that 463 patients were discharge for having some type of PCL injury. The 18- to 44-year-old age group was found to have the highest injuries reported (figure 1). One reason why this age group consists of the majority of injuries to the PCL is because people are still very active in sports at this age. Men were also reported having more injuries to the PCL (figure 3).

Recommendation for surgery

A grade III PCL injury with more than 10mm posterior translation when the posterior drawer examination is performed may be treated surgically. Patients that do not improve stability during physical therapy or develop an increase in pain will be recommended for surgery.[26]

References

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

- ↑ Jonathan Cluett, M.D. (2003-08-05). "Injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)". about.com. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ↑ Posterior Sag Test From The University of West Alabama, Athletic Training & Sports Medicine Center. Retrieved Feb 2011

- ↑ Cole, Brian; Miller, Mark J. (2004). Textbook of arthroscopy. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 719. ISBN 0-7216-0013-1.

- ↑ Amis, A. A.; Gupte, C. M.; Bull, A. M. J.; Edwards, A. (2006). "Anatomy of the posterior cruciate ligament and the meniscofemoral ligaments". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 14 (3): 257–63. doi:10.1007/s00167-005-0686-x. PMID 16228178.

- ↑ Girgis, FG; Marshall, JL; Monajem, A (1975). "The cruciate ligaments of the knee joint. Anatomical, functional and experimental analysis". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 106: 216–31. doi:10.1097/00003086-197501000-00033. PMID 1126079.

- 1 2 3 Chandrasekaran, Sivashankar; Ma, David; Scarvell, Jennifer M.; Woods, Kevin R.; Smith, Paul N. (2012). "A review of the anatomical, biomechanical and kinematic findings of posterior cruciate ligament injury with respect to non-operative management". The Knee. 19 (6): 738–45. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2012.09.005. PMID 23022245.

- ↑ Edwards, A.; Bull, AM.; Amis, AA. (Mar 2007). "The attachments of the fiber bundles of the posterior cruciate ligament: an anatomic study.". Arthroscopy. 23 (3): 284–90. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2006.11.005. PMID 17349472.

- 1 2 3 Voos, J. E.; Mauro, C. S.; Wente, T.; Warren, R. F.; Wickiewicz, T. L. (2012). "Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Outcomes". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 40 (1): 222–31. doi:10.1177/0363546511416316. PMID 21803977.

- 1 2 3 Malone, A.A.; Dowd, G.S.E.; Saifuddin, A. (2006). "Injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner of the knee". Injury. 37 (6): 485–501. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2005.08.003. PMID 16360655.

- ↑ DeFrate, L. E. (2004). "In Vivo Function of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament During Weightbearing Knee Flexion". American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (8): 1923–8. doi:10.1177/0363546504264896. PMID 15572322.

- ↑ Race, Amos; Amis, Andrew A. (1994). "The mechanical properties of the two bundles of the human posterior cruciate ligament". Journal of Biomechanics. 27 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(94)90028-0. PMID 8106532.

- ↑ Castle, Thomas H.; Noyes, Frank R.; Grood, Edward S. (1992). "Posterior Tibial Subluxation of the Posterior Cruciate-Deficient Knee". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (284): 193–202. doi:10.1097/00003086-199211000-00027. PMID 1395293.

- ↑ von Eisenhart-Rothe, Ruediger; Lenze, Ulrich; Hinterwimmer, Stefan; Pohlig, Florian; Graichen, Heiko; Stein, Thomas; Welsch, Frederic; Burgkart, Rainer (2012). "Tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint 3D-kinematics in patients with posterior cruciate ligament deficiency compared to healthy volunteers". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 13: 231. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-231. PMC 3517747

. PMID 23181354.

. PMID 23181354. - 1 2 3 4 Janousek, Andreas T.; Jones, Deryk G.; Clatworthy, Mark; Higgins, Laurence D.; Fu, Freddie H. (1999). "Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries of the Knee Joint". Sports Medicine. 28 (6): 429–41. doi:10.2165/00007256-199928060-00005. PMID 10623985.

- 1 2 Hamill, Joseph; Knutzen, Kathleen. (2009). Biomechanical basis of human movemen. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-9128-1.

- ↑ Rigby, J.; Porter, K. (2010). "Posterior cruciate ligament injuries". Trauma. 12 (3): 175–81. doi:10.1177/1460408610378792.

- ↑ Sancheti, P.; Razi, M.; Ramanathan, E. B. S.; Yung, P. (2010). "Injuries around the knee - Symposium". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (Suppl 1): i1. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.078725.1.

- ↑ Lucia, Alejandro; Daneshjoo, Abdolhamid; Mokhtar, Abdul Halim; Rahnama, Nader; Yusof, Ashril (2012). "The Effects of Injury Preventive Warm-Up Programs on Knee Strength Ratio in Young Male Professional Soccer Players". PLoS ONE. 7 (12): e50979. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050979. PMC 3513304

. PMID 23226553.

. PMID 23226553. - ↑ Hrysomallis, C (2007). "Relationship between balance ability, training and sports injury risk". Sports Medicine. 37 (6): 547–56. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737060-00007. PMID 17503879.

- ↑ Aaltonen, Sari; Karjalainen, Heli; Heinonen, Ari; Parkkari, Jari; Kujala, Urho M. (2007). "Prevention of sports injuries: systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Internal Medicine. 167 (15): 1585–92. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.15.1585. PMID 17698680.

- ↑ http://www.orthspec.com/pdfs/PCL-injuries.pdf[]

- ↑ Fernandez, Matthew; Pugh, David (2012). "Multimodal and interdisciplinary management of an isolated partial tear of the posterior cruciate ligament: a case report". Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 11 (2): 84–93. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2011.10.005. PMC 3368977

. PMID 23204951.

. PMID 23204951. - ↑ Wind, William M.; Bergfeld, John A.; Parker, Richard D. (2004). "Evaluation and Treatment of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Revisited". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (7): 1765–75. doi:10.1177/0363546504270481. PMID 15494347.

- ↑ Majewski et al.

- ↑ (Mariani teal., 2002)

External links

- lljoints at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (antkneejointopenflexed)

- Dealing with Torn Ligament in the Knee

- http://www.orthspec.com/pdfs/PCL-injuries.pdf