Post-war Britain

| Periods in English history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is the general history of Britain since 1945. For a political outline see History of the United Kingdom (1945–present)

The United Kingdom was one of the victors in World War II. The cost of the war was very heavy, and the late 1940s were a time of austerity and cut-back. The Labour Party was in control 1945-51. It gave independence to India in 1947. The other major colonies became independent later, usually in the 1950s under the Conservative Party. The handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997 marked the virtual end of the British Empire, with only a few small territories left.[1] It was a founding member of the United Nations in 1945, with a veto in the Security Council. It collaborated closely with the United States during the Cold War after 1947, and in 1949 helped form NATO as a military alliance against the Soviet Union. It fought North Korea and China in the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. After a long debate and initial rejection, it joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973, but in 2016 decided to leave by 2019.

Prosperity returned in the 1950s and London remained a world centre of finance and culture, but the nation was no longer a superpower.[2] In foreign policy Britain promoted the Commonwealth (in the economic sphere) and the Atlantic Alliance (in the military sphere). In domestic policy a Post-war consensus saw the leadership of the Labour and Conservative parties largely agreed on Keynesian policies, with support for unions, regulation of business, and for nationalization of many older industries. The 1970s saw increasing economic problems with slow growth, higher unemployment, deindustrialisation, and continued labour strife. Conservative Margaret Thatcher (1979-1990) rejected the Post-war consensus in the 1980s, and denationalized most industries. A "New Labour" movement under Tony Blair (1997-2007) accepted most of the Thatcher policies in the early 20th century. Devolution became a major topic, as Scotland gained more local control but voted 55% to 45% in 2014 to remain in the UK. Dissatisfaction with immigration from Europe, and European Union (EU) controls led angry voters in 2016 to decide 52%-48% for Brexit, that is to withdraw from the EU.

Age of Austerity

1945 Labour victory

With the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, the coalition dissolved, triggering the 1945 general election. The result were a surprise as Labour won a landslide victory, winning just under 50% of the vote with a majority of 145 seats. The new Prime Minister Clement Attlee himself proclaimed, "This is the first time in the history of the country that a labour movement with a socialist policy has received the approval of the electorate."[3]

During the war, public opinion surveys showed public opinion moving to the left and in favour of wide social reform. There was little public appetite for a return to the poverty and mass unemployment of the interwar years which had become associated with the Conservatives.[4] Historian Henry Pelling, noting that polls showed a steady Labour lead after 1942, explains the long-term forces that caused the Labour landslide. He points to the usual swing against the party in power; the Conservative loss of initiative; wide fears of a return to the high unemployment of the 1930s; the theme that socialist planning would be more efficient in operating the economy; and the mistaken belief that Churchill would continue as prime minister regardless of the result.[5] The Labour Party victory in 1944 represented pent-up frustrations. The strong sense that all Britons had joined in a "People's War" and all deserved a reward animated voters.

As the war ended and American Lend Lease suddenly and unexpectedly ended, the Treasury was near bankruptcy and Labour's new programmes would be expensive. Prewar levels of prosperity did not return until the 1950s. It was called the Age of Austerity.[6]

Britain was almost bankrupt as a result of the war and yet was still maintaining a global empire in an attempt to remain a global power. For instance, it continued having a large air force and conscript army. When the US suddenly and without warning cut off Lend-Lease funding in September 1945, bankruptcy loomed. The government pleaded for help and secured a low-interest $3.75 billion loan from the US in December 1945.[7] The cost of rebuilding necessitated austerity at home in order to maximise export earnings, while Britain's colonies and other client states were required to keep their reserves in pounds as "sterling balances". Additional funds – that did not have to be repaid – came from the Marshall Plan in 1948–50, which also required Britain to modernise its business practices and remove trade barriers. Britain was an enthusiastic supporter of the Marshall Plan, and used it as a lever to more directly promote European unity and the NATO military alliance which formed in 1949.[8]

Conditions were grim; pre-war levels of prosperity did not return until the 1950s. Rationing and conscription continued on into the post war years as the government tried to control demand and normalise the economy. This anxieties were heightened when the country suffered one of the worst winters on record in 1946–47, as the coal and railway systems failed, factories closed and people were very cold.[9]

Wartime rationing continued, and was for the first time extended to bread in order to feed the German civilians in the British sector of occupied Germany.[10] During the war the government had banned ice cream and rationed sweets, such as chocolates and confections; sweets were rationed until 1954.[11] Most people grumbled, but for the poorest, rationing was beneficial, because their rationed diet was of greater nutritional value than their pre-war diet. Housewives organised to oppose the austerity.[12] The Conservatives saw their opening and rebuilt their fortunes by attacking socialism, austerity, rationing, and economic controls, and were back in power by 1951.[13]

There were some bright spots to cheer up the gloom. Morale was boosted by the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1947 and the Festival of Britain in 1951.[14] The 1948 Summer Olympics took place in London. Reconstruction had begun in the battered host city, but there was no funding for new facilities. All the venues for the Games were lent by private or public organisations, with little expenditure allocated for rebuilding.[15]

Labour Government

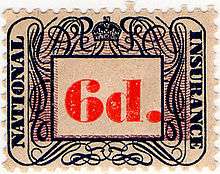

The most important Labour reforms were the expansion of the welfare state, the founding the National Health Service, and nationalizing coal, banking, railways and some other main industries. The welfare state was expanded with the National Insurance Act 1946, which built upon the comprehensive system of social security originally set up in 1911.[16] All persons of working age had to pay a weekly contribution (by buying a stamp) and in return were entitled to a wide range of benefits, including Guardian’s (or Orphans) Allowances, Death Grants, Unemployment Benefit, Widow’s Benefits, Sickness Benefit, and Retirement Pension.[17]

The National Health Service began operations in July 1948. It promised to give cradle to grave free hospital and medical care for everyone in the country, regardless of income.

Labour went on to expand low cost council housing for the poor, and nationalisation of the major industries.[18]

Economic challenges

The Treasury, headed by Hugh Dalton as Chancellor of the Exchequer, faced urgent problems. Half of the wartime economy had been devoted to mobilising soldiers, warplanes, bombs and munitions; an urgent transition to a peacetime budget was necessary, while minimising inflation. Financial aid through Lend-Lease from the United States was abruptly and unexpectedly terminated in September 1945, and new loans from the US and Canada were essential to keep living conditions tolerable. In the long run, Labour was committed to nationalisation of industry and national planning of the economy; more taxation of the rich and less of the poor; expanding the welfare state; and creating a free medical service for everyone.[19]

Nationalisation

.jpg)

Francis (1995) argues there was Labour Party consensus by 1945, both in the national executive committee and at party conferences, on a definition of socialism that stressed moral improvement as well as material improvement. The Attlee government was committed to rebuilding British society as an ethical commonwealth, using public ownership and controls to abolish extremes of wealth and poverty. Labour's ideology contrasted sharply with the contemporary Conservative Party's defence of individualism, inherited privileges, and income inequality.[20]

Attlee's government nationalised major industries and utilities. It developed and implemented the "cradle to grave" welfare state conceived by the Liberal economist William Beveridge. To this day the party considers the 1948 creation of Britain's publicly funded National Health Service under health minister Aneurin Bevan its proudest achievement.[21]

Labour Party experts went into the files to find the detailed plans for nationalisation that had been developed. To their surprise, there were no plans. The leaders realised they had to act fast to keep up the momentum. They started with the Bank of England, civil aviation, coal, and cables and wireless. Then came railways, canals, road haulage and trucking, electricity, and gas. Finally came iron and steel, which was a special case because it was a manufacturing industry. Altogether, about one fifth of the economy was taken over. Labour dropped its plans to nationalise farmlands.

On the whole nationalization went smoothly with few protests, but there were two exceptions. Nationalizing hospitals was strongly opposed by one element, the practicing physicians. Compromises were made to allow them to simultaneously have a private practice, and the great majority decided to work with the National Health Service. Much more controversy was the nationalization of the iron and steel industry-- unlike coal, it was profitable and highly efficient, and nationalization was opposed by the industry owners and executives, the business community as a whole, and the Conservative Party as a whole. House of Lords also was opposed, but new legislation limited its delaying power to only one year. Finally in 1951, iron and steel was nationalized, but then Labour lost its majority and the Conservatives In 1955, returned it to private ownership.[22]

The procedure used was developed by Herbert Morrison, who as Lord President chaired the Committee on the Socialisation of Industries. He followed the model that was already in place of setting up public corporations such as the BBC in broadcasting (1927). The owners of corporate stock were given government bonds, and the government took full ownership of each affected company, consolidating it into a national monopoly. The managers remained the same, only now they became civil servants working for the government. For the Labour Party leadership, nationalisation was a way to consolidate economic planning in their own hands. It was not designed to modernise old industries, make them efficient, or transform their organisational structure. There was no money for modernisation, although the Marshall Plan, operated separately by American planners, did force many British businesses to adopt modern managerial techniques. Old line socialists were disappointed, as the nationalised industries seemed identical to the old private corporations, and national planning was made virtually impossible by the government’s financial constraints. Socialism was in place, but it did not seem to make a major difference. Rank-and-file workers had long been motivated to support Labour by tales of the mistreatment of workers by foremen and the management. The foremen and the managers were the same people as before, with much the same power over the workplace. There was no worker control of industry. The unions resisted government efforts to set wages. By the time of the general elections in 1950 and 1951, Labour seldom boasted about nationalisation of industry. Instead it was the Conservatives who decried the inefficiency and mismanagement, and promised to reverse the treatment of steel and trucking.[23][24]

Labour's weakness

As the rosy dreams of 1945 gave way to harsh reality in the late 1940s, Labour struggled to maintain its support. Realising the unpopularity of rationing, in 1948–49 the government ended the rationing of potatoes, bread, shoes, clothing and jam, and increased the petrol ration for summer drivers. However, meat was still rationed, and in very short supply, at high prices.[25] Tempers grew short and the rhetoric shrill. The militant socialist Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health, said at a party rally in 1948, "no amount of cajolery... can eradicate from my heart a deep burning hatred for the Tory Party.... They are lower than vermin." Bevan, a coal miner's son, had gone too far in a land that took pride in self-restraint and never lived down the remark.[26]

Labour narrowly won the 1950 general election with a majority of five seats. Troubles mounted, and Attlee lost his knack of keeping all the factions together. Defence became one of the divisive issues for Labour itself, especially defence spending, which reached 14% of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War. These costs put enormous strain on public finances, forcing savings to be found elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell introduced prescription charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, causing Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (President of the Board of Trade) to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment. A decade of turmoil ensued in the Party, much to the advantage of the Conservatives who won again and again by ever larger majorities.[27]

Kynaston argues that the Labour Party under Prime Minister Clement Attlee was led by conservative parliamentarians who always worked through constitutional parliamentary channels; they saw no need for large demonstrations, boycotts or symbolic strikes. The result was a solid expansion and coordination of the welfare system, most notably the concentrated and centralised National Health Service. Nationalisation of the private sector focused on older, declining industries, most notably coal mining. Labour kept promising systematic economic planning, but they did not set up adequate mechanisms. Much of the planning was forced upon them by the American Marshall Plan, which insisted on a modernisation of business procedures and government regulations.[28] The Keynesian model accepted by Labour emphasised that planning could be handled indirectly through national spending and tax policies.[29]

Foreign policy

Britain faced severe financial crises – there was very little cash for needed imports. It responded by reducing its international entanglements as in Greece, and by sharing the hardships of an "age of austerity."[30] Britain eagerly supported the Marshall Plan in 1948, with its grants (with no repayment) that rebuilt and modernised infrastructure and business practices, and lowered trade barriers within Europe. Fears that Washington would veto nationalisation or welfare policies proved groundless.[31]

Under Attlee foreign policy was the domain of Ernest Bevin, who looked for innovative ways to bring western Europe together in a military alliance. One early attempt was the Dunkirk Treaty with France in 1947.[32] Bevin's commitment to the West European security system made him eager to sign the Brussels Pact in 1948. It drew Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg into an arrangement for collective security, opening the way for the formation of NATO in 1949. NATO was primarily aimed as a defensive measure against Soviet expansion, but it also helped bring its members closer together and enabled them to modernise their forces along parallel lines, and encourage arms purchases from Britain.[33]

Bevin began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1948.[34] In January 1947, the government decided to proceed with the development of Britain's nuclear weapons programme, primarily to enhance Britain's security and also its status as a superpower. A handful of top elected officials made the decision in secret, ignoring the rest of the cabinet, in order to forestall the pacifist and anti-nuclear Left wing of the Labour Party.[35]

Popular dissatisfaction

In the late 1940s the Conservative Party exploited and incited growing public anger at food rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity, and omnipresent government bureaucracy. They used the dissatisfaction with the socialistic and egalitarian policies of the Labour Party to rally middle-class supporters and build a political comeback that won the 1951 general election. Their appeal was especially effective to housewives, who faced more difficult shopping conditions after the war than during it.[36]

Churchill returns

The success of the Conservative Party in reorganising itself was validated by its victory in the 1951 election. It had restored its credibility on economic policy with the Industrial Charter written by Rab Butler, which emphasised the importance of removing unnecessary controls, while going far beyond the laissez-faire attitude of old towards industrial social problems. Churchill was party leader, but he brought in a Party Chairman to modernise the creaking institution. Lord Woolton was a successful department store owner and wartime Minister of Food. As Party Chairman 1946–55, he rebuilt the local organisations with an emphasis on membership, money, and a unified national propaganda appeal on critical issues. To broaden the base of potential candidates, the national party provided financial aid to candidates, and assisted the local organisations in raising local money. Lord Woolton emphasised a rhetoric that characterised the opponents as "Socialist" rather than "Labour." The libertarian influence of Professor Friedrich Hayek's 1944 best-seller Road to Serfdom was apparent in the younger generation, but that took another quarter century to have a policy impact. By 1951, Labour had worn out its welcome in the middle classes; its factions were bitterly embroiled. Conservatives were ready to govern again.[37]

Conservatives narrowly won the October 1951 election; Churchill was back. Most of the new programmes passed by Labour were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post war consensus", which lasted until the 1970s.[38] The Conservatives ended rationing and reduced controls. They were conciliatory towards unions but they did de-nationalise the steel and road haulage industries in 1953.[39]

The Media

The powerful press barons had less political power after 1945. Stephen Koss explains that the decline was caused by structural shifts: the major Fleet Street papers became properties of large, diversified capital empires with more interest in profits than politics; the provincial press virtually collapsed, with only the Manchester Guardian playing a national role; growing competition arose from non-political journalism and from other media such as the BBC; and independent press lords emerged who were independent of the party agents and leaders.[40]

Prosperity of the 1950s

As the country headed into the 1950s, rebuilding continued, and a steady flow began of immigrants from Commonwealth nations: mostly the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent. The shock of the Suez Crisis of 1956 made brutally clear that Britain had lost its role as a superpower. It already knew it could no longer afford its large Empire. This led to decolonisation, and a withdrawal from almost all of its colonies by 1970.

The 1950s and 1960s were, however, relatively prosperous times and saw continued modernisation of the economy, including the construction of its first motorways, for example. Britain maintained and increased its financial role in the world economy, and used the English language to promote its educational system to students from around the globe. Unemployment was relatively low during this period, and the standard of living continued to rise, with more new private and council housing developments and the number of slum properties diminishing. Churchill and the Conservatives were back in power following the 1951 elections, but they largely continued the welfare state policies as set out by the Labour Party in the late 1940s.

During the "golden age" of the 1950s and 1960s, unemployment in Britain averaged 2%. As prosperity returned, Britons became more family centred.[41] Leisure activities became more accessible to more people after the war. Holiday camps, which had first opened in the 1930s, became popular holiday destinations in the 1950s – and people increasingly had the money to pursue their personal hobbies. The BBC's early television service was given a major boost in 1953 with the coronation of Elizabeth II, attracting a worldwide audience of twenty million, plus tens of millions more by radio, proving an impetus for middle-class people to buy televisions. In 1950 just 1% owned television sets; by 1965 25% did. As austerity receded after 1950 and consumer demand kept growing, the Labour Party hurt itself by shunning consumerism as the antithesis of the socialism it demanded.[42]

Small neighbourhood stores were increasingly replaced by chain stores and shopping centres, with their wide variety of goods, smart advertising, and frequent sales. Cars were becoming a significant part of British life, with city-centre congestion and ribbon developments springing up along many of the major roads. These problems led to the idea of the green belt to protect the countryside, which was at risk from development of new housing units.[43]

The post-war period witnessed a dramatic rise in the average standard of living, with a 40% rise in average real wages from 1950 to 1965.[44] Workers in traditionally poorly paid semi-skilled and unskilled occupations saw a particularly marked improvement in their wages and living standards. In terms of consumption, there was more equality, especially as the landed gentry was hard pressed to pay its taxes and had to reduce its level of consumption. As a result of wage rises, consumer spending also increased by about 20% during the same period, while economic growth remained at about 3%. In addition, food rations were lifted in 1954 while hire-purchase controls were relaxed in the same year. As a result of these changes, large numbers of the working classes were able to participate in the consumer market for the first time.[45] Entitlement to various fringe benefits was improved. In 1955, 96% of manual labourers were entitled to two weeks' holiday with pay, compared with 61% in 1951. By the end of the 1950s, Britain had become one of the world's most affluent countries, and by the early Sixties, most Britons enjoyed a level of prosperity that had previously been known only to a small minority of the population.[46] For the young and unattached there was, for the first time in decades, spare cash for leisure, clothes, and luxuries. In 1959, Queen magazine declared that "Britain has launched into an age of unparalleled lavish living." Average wages were high while jobs were plentiful, and people saw their personal prosperity climb even higher. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan claimed that "the luxuries of the rich have become the necessities of the poor." As summed up by R. J. Unstead,

- "Opportunities in life, if not equal, were distributed much more fairly than ever before and\ the weekly wage-earner, in particular, had gained standards of living that would have been almost unbelievable in the thirties."[47]

As noted by Martin Pugh,

- "Keynesian economic management enabled British workers to enjoy a golden age of full employment which, combined with a more relaxed attitude towards working mothers, led to the spread of the two-income family. Inflation was around 4 per cent, money wages rose from an average of £8 a week in 1951 to £15 a week by 1961, home-ownership spread from 35 per cent in 1939 to 47 per cent by 1966, and the relaxation of credit controls boosted the demand for consumer goods."[48]

By 1963, 82% of all private households had a television, 72% a vacuum cleaner, 45% a washing machine, and 30% a refrigerator. John Burnett notes that ownership had spread down the social scale so that the gap between consumption by professional and manual workers had considerably narrowed. The provision of household amenities steadily improved in the late decades of the century. From 1971 to 1983, households having the sole use of a fixed bath or shower rose from 88% to 97%, and those with an internal WC from 87% to 97%. In addition, the number of households with central heating almost doubled during that same period, from 34% to 64%. By 1983, 94% of all households had a refrigerator, 81% a colour television, 80% a washing machine, 57% a deep freezer, and 28% a tumble-drier.[49]

From a European perspective, however, Britain was not keeping pace. Between 1950 and 1970, it was overtaken by most of the countries of the European Common Market in terms of the number of telephones, refrigerators, television sets, cars, and washing machines per 100 of the population.[50] Education grew, but not as fast as in rival nations. By the early 1980s, some 80% to 90% of school leavers in France and West Germany received vocational training, compared with 40% in the United Kingdom. By the mid-1980s, over 80% of pupils in the United States and West Germany and over 90% in Japan stayed in education until the age of eighteen, compared with barely 33% of British pupils.[51] In 1987, only 35% of 16- to 18-year-olds were in full-time education or training, compared with 80% in the United States, 77% in Japan, 69% in France, and 49% in the United Kingdom.[52]

Northern Ireland, the Troubles to the Belfast Agreement

In the 1960s, moderate Unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Terence O'Neill tried to reform the system and give a greater voice to Catholics, who comprised 40% of the population of Northern Ireland. His goals were blocked by militant Protestants led by the Rev. Ian Paisley.[53] The increasing pressures from nationalists for reform and from unionists for "No surrender" led to the appearance of the civil rights movement under figures like John Hume and Austin Currie. Clashes escalated out of control, as the army could barely contain the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Ulster Defence Association. British leaders feared their withdrawal would lead to a "doomsday scenario", with widespread communal strife, followed by the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of refugees. London shut down Northern Ireland's parliament and began direct rule. By the 1990s, the failure of the IRA campaign to win mass public support or achieve its aim of a British withdrawal led to negotiations that in 1998 produced the 'Good Friday Agreement'. This won popular support and largely ended the most violent aspects of The Troubles.[54][55]

Crisis of the 1970s

The 1970s saw the fading away of the exuberance and the radicalism of the 1960s. Instead there was a mounting series of economic crises, marked especially by labour union strikes, as the British economy slipped further and further behind European and world growth. The result was a major political crisis, and a Winter of Discontent in the winter of 1978–79 in during which there were widespread strikes by public sector unions that serious inconvenienced and angered the public.[56][57]

Historians Alan Sked and Chris Cook have summarized the general consensus of historians regarding Labour in power in the 1970s:

- If Wilson's record as prime minister was soon felt to have been one of failure, that sense of failure was powerfully reinforced by Callahan's term as premier. Labour, it seemed, was incapable of positive achievements. It was unable to control inflation, unable to control the unions, unable to solve the Irish problem, unable to solve the Rhodesian question, unable to secure its proposals for Welsh and Scottish devolution, unable to reach a popular modus vivendi with the Common Market, unable even to maintain itself in power until it could go to the country and the date of its own choosing. It was little wonder, therefore, that Mrs. Thatcher resoundingly defeated it in 1979.[58]

Thatcher era: 1979–90

Margaret Thatcher was the dominant political force of the late 20th century, and often compared to Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George for her transformative powers. She was Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990, and Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990. She was often called the "Iron Lady" for her uncompromising politics and leadership style.[59]

Political analyst Dennis Kavanagh concludes that the "Thatcher Government produced such a large number of far-reaching changes across much of the policy spectrum, that it passes 'reasonable' criteria of effectiveness, radicalism, and innovation."[60]

1979 general election

The Labour party under James Callaghan (prime minister 1976–79) contested the May 1979 election as unemployment passed the one-million mark and unions became more aggressive. The Conservatives used a highly effective poster created by Saatchi and Saatchi, showing a dole queue snaking into the distance and it carried the caption "Labour isn't working". Voters gave Conservatives 43.9% of the vote and 339 seats to Labour's 269, for an overall majority of 43 seats. People generally voted against Labour rather than for the Conservatives. Labour was weakened by the steady long-term decline in the proportion of manual workers in the electorate. Twice as many manual workers normally voted Labour as voted Conservative, but they now constituted only 56% of the electorate. When Harold Wilson won narrowly for Labour in 1964, they had accounted for 63%. Furthermore, they were beginning to turn against the trade unions – alienated, perhaps, by the difficulties of the winter of 1978–9. In contrast, Tory policies stressed wider home ownership, which Labour refused to match. Thatcher did best in districts where the economy was relatively strong and was weaker where it was contracting.[61]

Thatcherism

As Prime Minister, she implemented policies that have come to be known as Thatcherism. After leading her Conservative party to victory in the 1979 general election she introduced a series of political and economic initiatives intended to reverse high unemployment and Britain's struggles in the wake of the Winter of Discontent and an ongoing recession. Her political philosophy and economic policies emphasised deregulation (particularly of the financial sector), flexible labour markets, the privatisation of state-owned companies, and reducing the power and influence of trade unions. Due to recession and high unemployment, Thatcher's popularity during her first years in office waned until the beginning of 1982, a few months before the Falklands War. She won re-election in 1983.[62]

Privatisation was an enduring legacy of Thatcherism; it was accepted by the Labour administration of Tony Blair. Her policy was to privatise nationalised corporations (such as the telephone and aerospace firms). She sold public housing to tenants, all on favourable terms. The policy developed an important electoral dimension during the second Thatcher government (1983–90). It involved more than denationalisation: wider share ownership was the second plank of the policy, and this provides an important historical perspective on the relationship between Thatcherism and 20th-century conservatism.[63] Thatcher preached the goal of achieving an "enterprise society" in Britain, especially in widespread share-ownership, sale of council houses, declining controls imposed by trade unions, and expansion of private health care. These policies radically transformed many central aspects of British society.[64]

Foreign policy

Thatcher was distrustful of the European Union and did not try to forge closer relations. Her major breakthrough in foreign policy came in the dramatic long-distance war against Argentina for control of the Falkland Islands.[65] Thatcher played a role in the ending of the Cold War. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, she provided support for U.S. President Jimmy Carter's aggressive response, such as the Olympic boycott. However, Britain's precarious economic situation at the time of the invasion led the British government to provide only tepid backing to Carter in his attempt to punish Moscow through economic sanctions.[66] She collaborated closely with the diplomacy of Ronald Reagan in confronting the Soviets. She was the first major western leader to identify Mikhail Gorbachev as someone we can work with. She was annoyed by Reagan's invasion of Grenada (a member of the Commonwealth), and lukewarm support regarding the Falklands.[67]

Thatcher was re-elected for a third term in 1987. During this period her support for a Community Charge (popularly referred to as "poll tax") was widely unpopular and her views on the European Community were not shared by others in her Cabinet. She resigned as Prime Minister and party leader in November 1990.

Cultural movements

The environmentalism movements of the 1980s reduced the emphasis on intensive farming, and promoted organic farming and conservation of the countryside.[68]

Protestant religious observance declined notably in Britain during the second half of the 20th century. Catholicism (based on the Irish elements) held its own, while the rapid growth came from Islam. Church of England attendance has particularly dropped, although charismatic churches like Elim and AOG are growing. The movement to Keep Sunday Special seemed to have lost at the beginning of the 21st century.[69]

The economy after 1979

After the relative prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s, the UK experienced extreme industrial strife and stagflation through the 1970s following a global economic downturn; Labour had returned to government in 1964 under Harold Wilson to end 13 years of Conservative rule. The Conservatives were restored to government in 1970 under Edward Heath, who failed to halt the country's economic decline and was ousted in 1974 as Labour returned to power under Harold Wilson. The economic crisis deepened following Wilson's return and the mood blackened more under his successor James Callaghan.

A deregulation of the economy ended the post-war consensus about the planned economy. It was the special goal of controversial Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher following her election as prime minister in 1979. The election came at a time of crises between the Labour Party and the trade unions, and a strong trend of higher unemployment and deindustrialisation. The 1970s saw the closure of much of Britain's manufacturing industries, with Scotland and Wales hardest hit. It was a time of financial boom as stock markets became liberalised and State-owned industries became privatised. Inflation also fell during this period and trade union power was reduced.

The National Union of Mineworkers had long been one of the strongest labour unions. Its strikes had toppled governments in the 1970s. Thatcher drew the line and defeated it in the bitterly fought miners' strike of 1984–1985. The basic problem was that the easy coal had all been mined and what was left was very expensive. The miners, however, were fighting not just for high wages but for a way of life that had to be subsidised by other workers. The Union split; its strategy was flawed. In the end almost all the mines were shut down. Britain turned to its vast reserves of North Sea gas and oil, which brought in substantial tax and export revenues, to fuel the new economic boom.

After the economic boom of the 1980s a brief but severe recession occurred between 1990 and 1992 following the economic chaos of Black Wednesday under government of Conservative John Major, who had succeeded Thatcher in 1990. However the rest of the 1990s saw the beginning of a period of continuous economic growth that lasted over 16 years and was greatly expanded under the New Labour government of Tony Blair following his landslide election victory in 1997, with a rejuvenated party having abandoned its commitment to policies including nuclear disarmament and nationalisation of key industries, and no reversal of the Thatcher-led union reforms.

From 1964 up until 1996, income per head had doubled, while ownership of various household goods had significantly increased. By 1996, two-thirds of households owned cars, 82% had central heating, most people owned a VCR, and one in five houses had a home computer.[70] In 1971, 9% of households had no access to a shower or bathroom, compared with only 1% in 1990; largely due to demolition or modernisation of older properties which lacked such facilities. In 1971, only 35% had central heating, while 78% enjoyed this amenity in 1990. By 1990, 93% of households had colour television, 87% had telephones, 86% had washing machines, 80% had deep-freezers, 60% had video-recorders, and 47% had microwave ovens. Holiday entitlements had also become more generous. In 1990, nine out of ten full-time manual workers were entitled to more than four weeks of paid holiday a year, while twenty years previously only two-thirds had been allowed three weeks or more.[52] The post-war period also witnessed significant improvements in housing conditions. In 1960, 14% of British households had no inside toilet, while in 1967 22% of all homes had no basic hot water supply. By the Nineties, however almost all homes had these amenities together with central heating, which was a luxury just two decades before.[71]

Common Market (EEC), then EU, membership

Britain's wish to join the Common Market (as the European Economic Community was known in Britain) was first expressed in July 1961 by the Macmillan government, was negotiated by Edward Heath as Lord Privy Seal, but was vetoed in 1963 by French President Charles de Gaulle. After initially hesitating over the issue, Harold Wilson's Labour Government lodged the UK's second application (in May 1967) to join the European Community, as it was now called. Like the first, though, it was vetoed by de Gaulle in November that year.[72]

In 1973, as Conservative Party leader and Prime Minister, Heath negotiated terms for admission and Britain finally joined the Community, alongside Denmark and Ireland in 1973. In opposition, the Labour Party was deeply divided, though its Leader, Harold Wilson, remained in favour. In the 1974 General Election, the Labour Party manifesto included a pledge to renegotiate terms for Britain's membership and then hold a referendum on whether to stay in the EC on the new terms. This was a constitutional procedure without precedent in British history. In the subsequent referendum campaign, rather than the normal British tradition of "collective responsibility", under which the government takes a policy position which all cabinet members are required to support publicly, members of the Government (and the Conservative opposition) were free to present their views on either side of the question. A referendum was duly held on 5 June 1975, and the proposition to continue membership was passed with a substantial majority.[73]

The Single European Act (SEA) was the first major revision of the 1957 Treaty of Rome. In 1987, the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher enacted it into UK law.[74]

The Maastricht Treaty transformed the European Community into the European Union. In 1992, the Conservative government under John Major ratified it, against the opposition of his backbench Maastricht Rebels.[75]

The Treaty of Lisbon introduced many changes to the treaties of the Union. Prominent changes included more qualified majority voting in the Council of Ministers, increased involvement of the European Parliament in the legislative process through extended codecision with the Council of Ministers, eliminating the pillar system and the creation of a President of the European Council with a term of two and a half years and a High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy to present a united position on EU policies. The Treaty of Lisbon will also make the Union's human rights charter, the Charter of Fundamental Rights, legally binding. The Lisbon Treaty also leads to an increase in the voting weight of the UK in the Council of the European Union from 8.4% to 12.4%. In July 2008, the Labour government under Gordon Brown approved the treaty and the Queen ratified it.[76]

Devolution for Scotland and Wales

On 11 September 1997 (on the 700th anniversary of the Scottish victory over the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge) a referendum was held on establishing a devolved Scottish Parliament.[77] There was an overwhelming 'yes' vote for both establishing the parliament and granting it limited tax varying powers. Two weeks later, a referendum in Wales on establishing a Welsh Assembly was also approved, but with a very narrow majority. The first elections were held, and these bodies began to operate, in 1999. The creation of these bodies has widened the differences between the regions, especially in areas like healthcare.[78][79]

Blair period: 1997–2007

Tony Blair was leader of the Labour Party from 1994, and three times Prime Minister (1997–2007). With Gordon Brown he founded the movement known as New Labour. He was known internationally for his responsibility for British participation in the conflicts in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and --with prolonged controversy that still continues, in Iraq in close cooperation with President George W. Bush. The severest criticisms of Blair concerned his decision to go to war in Iraq in close cooperation with the United States.[80] Saddam was easily toppled, but an insurgency arose that every day attacked British and American forces as they sought to foster a sort of democracy in Iraq. They pulled out in 2011. By 2010 only 12% of British respondents to an opinion poll considered the Iraq war to have been a success.[81]

Blair sought to modernise Britain's public services, encourage enterprise and innovation in its private sector and keep its economy open to international commerce. Under his premiership, British governments made major changes to the British constitution by legislation that transferred decision-making to devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. [82]

Kavanagh has argued that by the 1980s, left-wing or socialist tendencies in the Labour Party divided the party and united its enemies:

- "Labour voters are not attracted by many 'socialist' policies, that is greater public ownership, comprehensive education, extending trade union rights, and redistribution. Such policies appear to unite supporters of other parties in rejection well serving to divide Labour voters."[83]

Blair moved the Labour Party in new directions, minimising the left-wing or socialists factions. He thereby broadened the appeal to middle-class and professional voters.

Blair was also anxious to escape from the Labour party's reputation for "tax-and-spend" domestic policies; he wanted instead to establish a reputation for fiscal prudence. He had undertaken in general terms to modernise the welfare state, but he had avoided undertaking to reduce poverty, achieve full employment, or reverse the increase in inequality that had occurred during the Thatcher administration. Once in office, however, his government launched a package of social policies designed to reduce unemployment and poverty. The commitment to modernise the welfare state was tackled by the introduction of "welfare to work" programmes[84][85] to motivate the unemployed to return to work instead of drawing benefit. Poverty reduction programmes were targeted at specific groups, including children and the elderly, and took the form of what were termed "New Deals".[86] There were also new tax credit allowances for low-income and single-parent families with children, and "Sure Start" progammes for under-fours in deprived areas. A "National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal"[87] was launched in 2001 with the objective of ensuring that "within 10 to 20 years no-one should be seriously disadvantaged by where they live"; a "Social Exclusion Unit"[88] was set up, and annual progress reports concerning the reduction of poverty and social exclusion were commissioned.[89][90]

Gordon Brown, 2007-10

Chancellor Gordon Brown replaced Blair as Prime Minister in 2007. After initial rises in opinion polls Labour's popularity declined with the onset of a worldwide recession in 2008, leading to poor results in local European elections in 2009. A year later, Labour lost 91 seats in the House of Commons at the 2010 general election, the party's biggest loss of seats in a single general election since 1931.[91] He was succeeded as Prime Minister by David Cameron, and as Leader of the Labour Party by Ed Miliband.

Recent events

Cameron

Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron (2010-2016) sought to rebrand the Conservatives, embracing an increasingly socially liberal position. The 2010 general election led to Cameron becoming Prime Minister as the head of a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. His premiership was marked by the ongoing negative economic effects of the late-2000s worldwide financial crisis. He faced a large deficit in government finances that he sought to reduce through austerity measures. His administration introduced large-scale changes to welfare, immigration policy, education, and healthcare.[92] His government privatised the Royal Mail and some other state assets, and legalised same-sex marriage. He won an easy reelection in 2015 with 330 seats in Commons against 296.

Brexit

The UK Independence Party (UKIP), a Eurosceptic political party, 1993. It rose to prominence after 2000, winning third place in the 2004 European elections, second place in the 2009 European elections and first place in the 2014 European elections, with 27.5% of the total vote.[93] Cameron won reelection in 2015 in part by promising a referendum on the EU, which he expected would easily defeat Brexit.

Unexpectedly the 'Leave' pro-Brexit campaign waxed strong primarily on issues relating to sovereignty and migration,[94] whereas the remain campaign focused on the economic impacts of leaving the EU. Polls showed more cited both the EU (32%) and migration (48%) as important issues than cited the economy (27%).[95]

Historiography

Post-war consensus

The post-war consensus is a historians' model of political agreement from 1945 to 1979, when newly elected Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher rejected and reversed it. .[96] The concept claims there was a widespread consensus that covered support for a coherent package of policies that were developed in the 1930s, promised during the Second World War, and enacted under Attlee. The policies dealt with a mixed economy, Keynesianism, and a broad welfare state.[97] In recent years the validity of the interpretation has been debated by historians.

The historians' model of the post-war consensus was most fully developed by Paul Addison.[98] The basic argument is that in the 1930s Liberal Party intellectuals led by John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge developed a series of plans that became especially attractive as the wartime government promised a much better post-war Britain and saw the need to engage every sector of society. The coalition government during the war, headed by Churchill and Attlee, signed off on a series of white papers that promised Britain a much improved welfare state. After the war. The promises included the national health service, and expansion of education, housing, and a number of welfare programs. It did not include the nationalization of all industries, which was a Labour Party design. The Labour Party did not challenge the system of elite public schools--They became part of the consensus, as did comprehensive schools. Nor did Labour challenge the primacy of Oxford and Cambridge. However, the consensus did call for building many new universities to dramatically broaden educational base of society. Conservatives did not challenge the socialized medicine of the National Health Service; indeed, they boasted they could do better job of running it.[99] Inform policy, the consensus called for an anti-Communist Cold War policy, decolonisation, close ties to NATO, the United States, and the Commonwealth, and slowly emerging ties to the European Community.[100]

The model states that from 1945 until the arrival of Thatcher in 1979, there was a broad multi-partisan national consensus on social and economic policy, especially regarding the welfare state, nationalized health services, educational reform, a mixed economy, government regulation, Keynesian macroeconoic, policies, and full employment. Apart from the question of nationalization of some industries, these policies were broadly accepted by the three major parties, as well as by industry, the financial community and the labour movement. Until the 1980s, historians generally agreed on the existence and importance of the consensus. Some historians such as Ralph Milibrand expressed disappointment that the consensus was a modest or even conservative package that blocked a fully socialized society.[101] Historian Angus Calder complained bitterly that the post-war reforms were an inadequate reward for the wartime sacrifices, and a cynical betrayal of the people's hope for a more just post-war society.[102] In recent years, there has been a historiographical debate on whether such a consensus ever existed.[103]

See also

- History of British society § Since 1945

- The Spirit of '45 (2013 documentary film)

References

- ↑ Piers Brendon, The Decline And Fall Of The British Empire (2010)

- ↑ Peter Clarke, Hope and Glory: Britain 1900–1990 (1996) chs 7, 8

- ↑ David Kynaston (2010). Austerity Britain, 1945–1951. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 75.

- ↑ Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour in Power: 1945–1951 (1985) ch 1

- ↑ Henry Pelling, "The 1945 general election reconsidered." Historical Journal 23#2 (1980): 399-414. in JSTOR

- ↑ David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 1945–51 (2008)

- ↑ Philip A. Grant Jr., "President Harry S. Truman and the British Loan Act of 1946," Presidential Studies Quarterly (1995) 25#3 pp 489–96

- ↑ Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour in Power: 1945–1951 (1984) pp 269–77

- ↑ Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls, and Consumption, 1939–1955 (2002)

- ↑ R. Gerald Hughes (2007). Britain, Germany and the Cold War: The Search for a European Détente 1949–1967. Taylor & Francis. p. 11.

- ↑ Richard Farmer, "'A Temporarily Vanished Civilisation': Ice Cream, Confectionery and Wartime Cinema-Going," Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, (December 2011) 31#4 pp 479–497,

- ↑ James Hinton, "Militant Housewives: The British Housewives' League and the Attlee Government," History Workshop, No. 38 (1994), pp. 128–156 in JSTOR

- ↑ Ina Zweiniger-Bargileowska, "Rationing, austerity and the Conservative party recovery after 1945," Historical Journal, (March 19940, 37#1 pp 173–97 in JSTOR

- ↑ Alfred F. Havighurst, Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century (1962) ch 10

- ↑ Sefryn Penrose, "London 1948: the sites and after-lives of the austerity Olympics," World Archaeology (2012) 44#2 pp 306–325.

- ↑ Rachel Reeves, and Martin McIvor. "Clement Attlee and the foundations of the British welfare state." Renewal: a Journal of Labour Politics 22#3/4 (2014): 42+. online

- ↑ N. A. Barr (1993). The Economics of the Welfare State. Stanford UP. p. 33.

- ↑ Jim Tomlinson, Democratic Socialism and Economic Policy: The Attlee Years, 1945–1951 (2002)

- ↑ Ben Pimlott, "Dalton, (Edward) Hugh Neale, Baron Dalton (1887–1962)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004)

- ↑ Martin Francis, "Economics and Ethics: The Nature of Labour's Socialism, 1945–1951," Twentieth Century British History (1995) 6#2 pp 220–243.

- ↑ See Proud of the NHS at 60 Labour Party. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Alan Sked and Chris Cook, Post-war Britain: A political history (1993) ch 2-4.

- ↑ Alan Sked and Chris Cook, Post-War Britain: A Political History (1979) pp 31–34

- ↑ Samuel H. Beer, British Politics in the Collectivist Age (1965) pp 188–216

- ↑ W. N. Medlicott, Contemporary England: 1914–1964 (1967) p506

- ↑ David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 1945–1951 (2008) p 284

- ↑ Michael Foot, Aneurin Bevan: 1945–1960 (1973) pp 280–346

- ↑ David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 1945–1951 (2008)

- ↑ Martin Pugh, State and Society: A Social and Political History of Britain since 1870 (4th ed. 2012) ch 16

- ↑ David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 1945–1951 (2008) ch 4

- ↑ James Williamson, "British Socialism and the Marshall Plan," History Today (2008) 59#2 pp 53–59.

- ↑ John Baylis, "Britain and the Dunkirk Treaty: The Origins of NATO," Journal of Strategic Studies (1982) 5#2 pp 236–247.

- ↑ John Baylis, "Britain, the Brussels Pact and the continental commitment," International Affairs (1984) 60#4 pp 615–29

- ↑ Piers Brendon, The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781–1997 (2010) ch 13–16

- ↑ Regina Cowen Karp, ed. (1991). Security With Nuclear Weapons: Different Perspectives on National Security. Oxford U.P. pp. 145–47.

- ↑ Ina Zweiniger-Bargileowska, "Rationing, austerity and the Conservative party recovery after 1945," Historical Journal (1994) 37#1 pp 173–97

- ↑ Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major (1997) pp 260–264

- ↑ Richard Toye, "From 'Consensus' to 'Common Ground': The Rhetoric of the Postwar Settlement and its Collapse," Journal of Contemporary History (2013) 48#1 pp 3–23.

- ↑ Kenneth O. Morgan (2001). Britain Since 1945: The People's Peace: The People's Peace. Oxford UP. pp. 114–5.

- ↑ Stephen Koss, The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain. Vol. II, The Twentieth Century (1981)

- ↑ David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–1957 (2009)

- ↑ Peter Gurney, "The Battle of the Consumer in Postwar Britain," Journal of Modern History (2005) 77#4 pp. 956–987 in JSTOR

- ↑ Willem van Vliet, Housing Markets & Policies under Fiscal Austerity (1987)

- ↑ Paul Addison and Harriet Jones, ed. A companion to contemporary Britain, 1939–2000

- ↑ Matthew Hollow (2011). 'The Age of Affluence': Council Estates and Consumer Society.

- ↑ C.P. Hill, British Economic and Social History 1700–1964

- ↑ R.J. Unstead, A Century of Change: 1837–Today (1963) p 224

- ↑ Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain! A New History of the Labour Party (Random House, 2011), pp 115–16

- ↑ John Burnett, A Social History of Housing 1815–1985 (1990) p 302

- ↑ Brian Lapping, The Labour Government 1964–70

- ↑ David McDowall, Britain in Close-Up

- 1 2 Anthony Sampson, The Essential Anatomy of Britain: Democracy in Crisis (1993) p 64

- ↑ Marc Mulholland, Northern Ireland at the Crossroads: Ulster Unionism in the O'Neill Years, 1960–9 (2000)

- ↑ Paul Dixon, Northern Ireland: The Politics of War and Peace (2008)

- ↑ Christopher Farrington, Ulster Unionism and the Peace Process in Northern Ireland (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006)

- ↑ Alwyn W. Turner, Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s (2008)

- ↑ Andy Beckett , When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (2009) excerpt and text search.

- ↑ Alan Sked and Chris Cook, Post-War Britain: A Political History (4th ed. 1993) p324.

- ↑ Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: From Grantham to the Falklands (2013)

- ↑ Dennis Kavanagh (1997). The Reordering of British Politics: Politics After Thatcher. Oxford U.P. p. 111.

- ↑ David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh, The British General Elections of 1979 (1979)

- ↑ John Campbell, The Iron Lady: Margaret Thatcher, from Grocer's Daughter to Prime Minister (2011)

- ↑ Richard Stevens, "The Evolution of Privatisation as an Electoral Policy, c. 1970–90." Contemporary British History (2004) 18#2 pp 47–75.

- ↑ P. Norris, "Thatcher's Enterprise Society and Electoral Change," West European Politics (1990) 13#1 pp 63–78

- ↑ Robin Renwick, A Journey with Margaret Thatcher: Foreign Policy Under the Iron Lady (2013)

- ↑ Daniel James Lahey, "The Thatcher government's response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, 1979–1980," Cold War History (2013) 13#1 pp 21–42.

- ↑ Richard Aldous, Reagan and Thatcher: The Difficult Relationship (2012)

- ↑ Peter Dauvergne (2009). The A to Z of Environmentalism. Scarecrow Press. pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Christie Davis (2006). The strange death of moral Britain. Transaction Publishers. p. 265.

- ↑ What Needs To Change: New Visions For Britain, edited by Giles Radice

- ↑ Homes less affordable than 50 years ago - but at least more of them have indoor toilets! | This is Money

- ↑ Thorpe, Andrew. (2001) A History Of The British Labour Party, Palgrave, ISBN 0-333-92908-X

- ↑ 1975: UK embraces Europe in referendum BBC On This Day

- ↑ Ever Closer Union – The Thatcher Era BBC

- ↑ Ever Closer Union – Backing away from Union BBC

- ↑ UK ratifies the EU Lisbon Treaty BBC

- ↑ Graham Walker, "Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Devolution, 1945–1979," Journal of British Studies (2010) 49#1 pp 117–142.

- ↑ See 'Huge contrasts' in devolved NHS BBC News, 28 August 2008

- ↑ NHS now four different systems BBC 2 January 2008

- ↑ Andrew Langley, Bush, Blair, and Iraq: Days of Decision (2013)

- ↑ See All things considered, do you think the Iraq War was a success or a failure?, Vision Critical, Aug 20 2010

- ↑ Anthony Seldon, ed. Blair's Britain, 1997–2007 (2007), ch 1, 8

- ↑ Denis Kavanagh, Thatcherism and British Politics: The End of Consensus? (1987) p 312

- ↑ See Martin Evans: Welfare to work and the organisation of opportunity, ESRC Research Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, 2001

- ↑ see Dan Finn: Modernisation or Workfare? New Labour's Work-Based Welfare State, ESRC Labour Studies Seminar,28 March 2000

- ↑ See Richard Beaudry: Workfare and Welfare: Britain’s New Deal, Working Paper Series # 2, The Canadian Centre for German and European Studies, 2002

- ↑ See Evaluation of the National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal – Final report, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2010

- ↑ See The Social Exclusion Unit, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister

- ↑ ["Opportunity for All: Tackling Poverty and Social Exclusion", Department for Social Security, 1999]

- ↑ See "Opportunity for All, 7th annual report, Department of Work and Pensions, 2005

- ↑ Maddox, David (7 May 2010). "General Election 2010: Gordon's career is finished – Labour MP". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ↑ Morris, Nigel (22 May 2014). "David Cameron sticks to his guns on immigration reduction pledge even while numbers rise". The Independent. London. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "10 key lessons from the European election results". The Guardian. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ↑ "EU referendum: Vote Leave focuses on immigration". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ↑ "Ipsos MORI | Poll | Concern about immigration rises as EU vote approaches". www.ipsos-mori.com. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ↑ Richard Toye, "From 'Consensus' to 'Common Ground': The Rhetoric of the Postwar Settlement and its Collapse," Journal of Contemporary History (2013) 48#1 pp 3-23.

- ↑ Dennis Kavanagh, "The Postwar Consensus," Twentieth Century British History (1992) 3#2 pp 175-190.

- ↑ Paul Addison, The road to 1945: British politics and the Second World War (1975).

- ↑ Rudolf Klein, "Why Britain's conservatives support a socialist health care system." Health Affairs 4#1 (1985): 41-58. online

- ↑ Michael R. Gordon, Conflict and consensus in Labour's foreign policy, 1914-1965 (1969).

- ↑ Ralph Miliband, Parliamentary socialism: A study in the politics of labour. (1972).

- ↑ Angus Calder, The Peoples War: Britain, 1939 – 1945 (1969).

- ↑ Daniel Ritschel, Daniel. "Consensus in the Postwar Period After 1945," in David Loades, ed., Reader's Guide to British History (2003) 1:296-297.

Further reading

- Addison, Paul and Harriet Jones, eds. A Companion to Contemporary Britain: 1939–2000 (2005) excerpt and text search, 30 essays on broad topics by scholars

- Addison, Paul. No Turning Back: The Peaceful Revolutions of Post-War Britain (2011) excerpt and text search

- Beckett, Andy. When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (2009) excerpt and text search.

- Black, Jeremy. Britain since the Seventies: Politics and Society in the Consumer Age (2012) excerpt and text search

- Cannon, John, ed. The Oxford Companion to British History (2003), historical encyclopedia; 4000 entries in 1046pp excerpt and text search

- Childs, David. Britain since 1945: A Political History (2012) excerpt and text search

- Clarke, Peter. Hope and Glory: Britain 1900–2000 (2nd ed. 2004) 512pp; excerpt and text search

- Cook, Chris and John Stevenson, eds. Longman Companion to Britain Since 1945 (1995) 336pp

- Foster, Laurel and Sue Harper, eds. British Culture and Society in the 1970s: The Lost Decade (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010). 310 pp.

- French, David. Army, Empire, and Cold War: The British Army and Military Policy, 1945-1971 (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Harrison, Brian Howard. Seeking a Role: The United Kingdom, 1951–1970 (New Oxford History of England) (2011) excerpt and text search; major survey with emphasis social history

- Harrison, Brian Howard. Finding a Role?: The United Kingdom 1970–1990 (New Oxford History of England) (2011) excerpt and text search

- Hennessy, Peter. Never Again: Britain, 1945-1951 (1994)), a major scholarly survey.

- Hennessy, Peter. Having it so good: Britain in the fifties (2007), a major scholarly survey.

- Holland, R.F. The pursuit of greatness: Britain and the world role, 1900–1970 (Fontana history of England) (1991)

- Jones, Harriet, and Mark Clapson, eds. The Routledge Companion to Britain in the Twentieth Century (2009) excerpt and text search

- Kynaston, David. Austerity Britain, 1945–1951 (2008) excerpt and text search, a major social history

- Kynaston, David. Family Britain, 1951–1957 (2009) excerpt and text search, a major social history

- Kynaston, David. Modernity Britain: 1957-1962 (2014), a major social history Excerpt

- Leventhal, F.M. Twentieth-Century Britain: An Encyclopedia (2nd ed. 2002) 640pp; short articles by scholars

- Marquand, David, and Anthony Seldon, eds. The Ideas That Shaped Post-war Britain (1996), history of political ideas

- Marr, Andrew. A History of Modern Britain (2009); also published as The Making of Modern Britain (2010), popular history covers 1945–2005

- Marwick, Arthur. The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, c.1958-c.1974 (Oxford UP, 1998, ISBN 978-0-19-210022-1)

- Moore, Charles. Margaret Thatcher: From Grantham to the Falklands (2013), vol. 1

- Morgan, Kenneth O. Labour in Power 1945–1951 (1985), influential study

- Morgan, Kenneth O. The Peoples Peace: British History 1945–1990 (1990)

- Otte, T.G. The Makers of British Foreign Policy: From Pitt to Thatcher (2002) excerpt and text search

- Ovendale, R. ed. The foreign policy of the British Labour governments, 1945–51 (1984)

- Pugh, Martin. Speak for Britain!: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) excerpt and text search

- Ramsden, John, ed. The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century British Politics (2005) excerpt and text search

- Sandbrook, Dominic. Never Had It So Good: A History of Britain from Suez to the Beatles (2006) 928pp; excerpt and text search

- Sandbrook, Dominic. White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties (2 vol 2007)

- Sandbrook, Dominic. State of Emergency: The Way We Were: Britain 1970–1974 (2011)

- Sandbrook, Dominic. Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979 (2013)

- Seldon, Anthony, and Daniel Collings, eds. Britain Under Thatcher (Routledge, 2014).

- Seldon, Anthony, ed. Blair's Britain, 1997–2007 (2007), essays by scholars excerpt and text search

- Sked, Alan, and Chris Cook. Post-War Britain: A Political History (1979)

- Stewart, Graham. Bang! A History of Britain in the 1980s (2013) excerpt and text search

- Tomlinson, Jim. Democratic Socialism and Economic Policy: The Attlee Years, 1945–1951 (2002) Excerpt and text search

- Tomlinson, Jim. The politics of decline: Understanding postwar Britain (Routledge, 2014).

- Turner, Alwyn W. Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s (2008)

- Turner, Alwyn W. Rejoice! Rejoice!: Britain in the 1980s (2013).

- Turner, Alwyn W. A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s (2013).

Statistics

- Halsey, A. H., ed. Twentieth-Century British Social Trends (2000) excerpt and text search; 762 pp of social statistics

- Mitchell, B. R. British Historical Statistics (2011); first edition was Mitchell and Phyllis Deane. Abstract of British Historical Statistics (1972) 532pp; economic and some social statistics

Historiography

- Bevir, Mark, and Rod A.W. Rhodes. "Narratives of ‘Thatcherism’." West European Politics 21.1 (1998): 97-119. online

- Jones, Harriet and Michael Kandiah, eds. The Myth of Consensus: New Views on British History, 1945-64 (1996) excerpt

- Marquand, David. "The literature on Thatcher." Contemporary British History 1.3 (1987): 30-31. online