Prehistoric Ireland

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ireland |

.jpg) |

| Chronology |

| Peoples and polities |

| Topics |

|

|

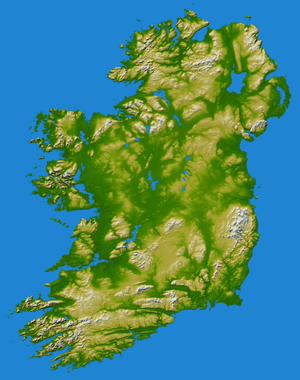

The prehistory of Ireland has been pieced together from archaeological and genetic evidence; it begins with the first evidence of humans in Ireland, 10,500 BC, and finishes with the start of the historical record, around AD 400. The prehistoric period covers the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age societies of Ireland. For much of Europe, the historical record begins when the Romans invaded; as Ireland was not invaded by the Romans its historical record starts later, with the coming of Christianity.

Palaeolithic

During the most recent Quaternary glaciation, ice sheets more than 3,000 m (9,800 ft) thick scoured the landscape of Ireland, pulverising rock and bone, and eradicating any possible evidence of early human settlements during the Glenavian warm period (human remains pre-dating the last glaciation have been uncovered in the extreme south of Britain, which largely escaped the advancing ice sheets).

During the Last Glacial Maximum (ca. 26,000–19,000 years ago),[1] Ireland was an Arctic wasteland, or tundra. The Midland General Glaciation ("Midlandian period") was originally thought to have covered two thirds of the country with ice.[2] Subsequent evidence from the past 50 years has shown this to be untrue and recent publications (Greenwood and Clark, 2009) suggest that ice went off the southern coast of Ireland. The early part of the Holocene had a climate that was inhospitable to most European animals and plants. Human occupation was unlikely, though fishing possible.

During the period between 17,500 and 12,000 years ago, a warmer period, the Bølling-Allerød, allowed the rehabitation of northern areas of Europe by roaming hunter-gatherers. Genetic evidence suggests this reoccupation began in southwestern Europe and faunal remains suggest a refugium in Iberia that extended up into southern France. The original attraction to the north during the pre-boreal period would be species like reindeer and aurochs. Some sites as far north as Sweden inhabited earlier than 10,000 years ago suggest that humans might have used glacial termini as places from which they hunted migratory game.

These factors and ecological changes brought humans to the edge of the northernmost ice-free zones of Europe by the onset of the Holocene and this included regions close to Ireland.

Britain and Ireland were joined by a land bridge, but because this link was cut so early into the warm period few temperate terrestrial flora or fauna crossed into Ireland.[3] The bridge was possibly gone by 14,000 BC, which is before the most recent stadial (cold period), the Younger Dryas.[3] The lowered sea level also joined Britain to continental Europe; this persisted much longer, probably until around 5600 BC.[4]

On the eastern side of the Irish Sea, a site dated to 11,000 BC was discovered that indicated people were in the area eating a marine diet including shellfish. These modern humans may have also colonised Ireland after crossing the southern, now ice-free, land bridge that linked south-east Ireland and Cornwall. This land bridge existed until about 14,000 BC.[5] These people may have found few resources outside of coastal shellfishing and acorns and so may not have continually occupied the region. However, a bear bone, found in Alice and Gwendoline Cave, County Clare in 1903, shows humans were in Ireland in 10,500 BC. It shows clear signs of cut marks with stone tools, and has been radiocarbon dated to 12,500 years ago.[6]

As the northern glaciers retreated, sea levels rose with water draining into an inland sea where the Irish Sea currently stands; the outflow of freshwater and eventual rise in sea level between the Irish and Celtic Seas inhibited the entry of flora and fauna from Europe via Britain. To this day snakes (and most other reptiles) have not made their way back to Ireland.[7]

The return of freezing conditions during the Younger Dryas, that occurred in Ireland between 10,900 BC and 9700 BC, may have depopulated Ireland. During the Younger Dryas sea-levels continued to rise and no ice-free land bridge between Great Britain and Ireland ever returned.[8]

Mesolithic (8000–4000 BC)

The last ice age came to an end in Ireland about 10–12 thousand years ago. The earliest evidence of human occupation after the retreat of the ice has been dated to around 8000 BC.[9] Evidence for Mesolithic hunter-gatherers has been found throughout the country: a number of the key early Mesolithic excavations are the settlement site at Mount Sandel in County Londonderry (Coleraine); the cremations at Hermitage, County Limerick on the bank of the River Shannon; and the campsite at Lough Boora in County Offaly. As well as these, early Mesolithic lithic scatters have been noted around the country, from the north in County Donegal to the south in County Cork.[9] Although sea levels were still lower than they are today, Ireland was already an island by the time the first settlers arrived (after 8000 BC). This was by boat from continental Europe. Most of the Mesolithic sites in Ireland are coastal settlements. The earliest inhabitants of this country were seafarers who depended for much of their livelihood upon the sea.

A DNA study of the first humans into Ireland concluded that Ireland was first settled around 9,000 years ago by people who travelled by land and sea up the coast from northern Spain and southern France.[10] This has since been challenged. (See Blood of the Irish).

The hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic era lived on a varied diet of seafood, birds, wild boar and hazelnuts. There is no evidence for deer in the Irish Mesolithic and it is likely that the first red deer were introduced in the early stages of the Neolithic.[11] The human population hunted with spears, arrows and harpoons tipped with small stone blades called microliths, while supplementing their diet with gathered nuts, fruit and berries. They lived in seasonal shelters, which they constructed by stretching animal skins over wooden frames. They had outdoor hearths for cooking their food. During the Mesolithic the population of Ireland was probably never more than a few thousand.

Neolithic (4000–2500 BC)

Many areas of Europe entered the Neolithic with a 'package' of cereal cultivars, pastoral animals (domesticated oxen/cattle, sheep, goats), pottery, weaving, housing and burial cultures, which arrive simultaneously, a process that begins in central Europe as LBK (Linear Pottery culture) about 6000 BC. Within several hundred years this culture is observed in northern France. An alternative Neolithic culture, La Hoguette culture, that arrived in France's north-western region appears to be a derivative of the Ibero Italian-Eastern Adriatic Impressed Cardial Ware culture (Cardium Pottery). The La Hoguette culture, like the western Cardial culture, raised sheep and goats more intensely. By 5100 BC there is evidence of dairy practices in south England and modern English cattle appear to be derived from "T1 Taurids" that were domesticated in the Aegean region shortly after the onset of the Holocene. These animals were probably derived from the LBK cattle. Around 4300 BC cattle arrived in northern Ireland during the late Mesolithic period. The red deer was introduced from Britain about this time.[11]

From around 4500 BC a Neolithic package that included cereal cultivars, housing culture (similar to those of the same period in Scotland) and stone monuments arrived in Ireland. Sheep, goats, cattle and cereals were imported from southwest continental Europe, and the population then rose significantly. At the Céide Fields in County Mayo, an extensive Neolithic field system (arguably the oldest known in the world) has been preserved beneath a blanket of peat. Consisting of small fields separated from one another by dry-stone walls, the Céide Fields were farmed for several centuries between 3500 and 3000 BC. Wheat and barley were the principal crops cultivated. Pottery made its appearance around the same time as agriculture. Ware, similar to that found in northern Great Britain, has been excavated in Ulster (Lyle's Hill pottery) and in Limerick. Typical of this ware are wide-mouthed, round-bottomed bowls.

This follows a pattern similar to western Europe or gradual onset of Neolithic, such as seen in La Hoguette Culture of France and Iberia's Impressed Cardial Ware Culture. Cereal culture advance markedly slows north of France; certain cereal strains such as wheat were difficult to grow in cold climates—however, barley and German rye were suitable replacements. It can be speculated that the DQ2.5 aspect of the AH8.1 haplotype may have been involved in the slowing of cereal culture into Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia since this haplotype confers susceptibility to a Triticeae protein induced disease as well as Type I diabetes and other autoimmune diseases that may have arisen as an indirect result of Neolithisation.

- Different types of megalithic tombs

-

Creevykeel court tomb, County Sligo.

-

Knowth, a passage tomb located at Brú na Bóinne.

-

Poulnabrone dolmen, a portal tomb located at The Burren.

-

Glantane East wedge tomb.

The most striking characteristic of the Neolithic in Ireland was the sudden appearance and dramatic proliferation of megalithic monuments. The largest of these tombs were clearly places of religious and ceremonial importance to the Neolithic population. In most of the tombs that have been excavated, human remains—usually, but not always, cremated—have been found. Grave goods—pottery, arrowheads, beads, pendants, axes, etc.—have also been uncovered. These megalithic tombs, more than 1,200 of which are now known, can be divided for the most part into four broad groups:

- Court tombs – These are characterised by the presence of an entrance courtyard. They are found almost exclusively in the north of the country and are thought to include the oldest specimens. North Mayo has many examples of this type of megalith – Faulagh, Kilcommon, Erris.

- Passage tombs – These constitute the smallest group in terms of numbers, but they are the most impressive in terms of size and importance. They are distributed mainly throughout the north and east of the country, the biggest and most impressive of them being found in the four great Neolithic "cemeteries" of the Boyne, Loughcrew (both in County Meath), Carrowkeel and Carrowmore (both in County Sligo). The most famous of them is Newgrange, a World Heritage Site and one of the oldest astronomically aligned monuments in the world. It was built around 3200 BC. At the winter solstice the first rays of the rising sun still shine through a light-box above the entrance to the tomb and illuminate the burial chamber at the centre of the monument. Another of the Boyne megaliths, Knowth, contains the world's earliest map of the Moon carved into stone.

- Portal tombs – These tombs include the well known dolmens. They consist of three or more upright stones supporting a large flat horizontal capstone (table). Most of them are to be found in two main concentrations, one in the southeast of the country and one in the north. The Knockeen and Gaulstown Dolmens in County Waterford are exceptional examples.

- Wedge tombs – The largest and most widespread of the four groups, the wedge tombs are particularly common in the west and southwest. County Clare is exceptionally rich in them. They are the latest of the four types and belong to the end of the Neolithic. They are so called from their wedge-shaped burial chambers.

The theory that these four groups of monuments were associated with four separate waves of invading colonists still has its adherents today, but the growth in population that made them possible need not have been the result of colonisation: it may simply have been the natural consequence of the introduction of agriculture.

Some regions of Ireland showed patterns of pastoralism that indicated that some Neolithic peoples continued to move and indicates that pastoral activities dominated agrarian activities in many regions or that there was a division of labour between pastoral and agrarian aspects of the Neolithic.

At the height of the Neolithic the population of the island was probably in excess of 100,000, and perhaps as high as 200,000. But there appears to have been an economic collapse around 2500 BC, and the population declined for a while.

Copper and Bronze Ages (2500–500 BC)

Metallurgy arrived in Ireland with new people, generally known as the Bell Beaker People, from their characteristic pottery, in the shape of an inverted bell.[12] This was quite different from the finely made, round-bottomed pottery of the Neolithic. It is found, for example, at Ross Island, and associated with copper mining there. There is some disagreement about when the Celts (and thus Indo-Europeans) first arrived in Ireland. It is thought by some scholars to be associated with the Beaker People of the Bronze Age, but the more mainstream view is that the Celts arrived much later at the beginning of the Iron Age.[13]

The Bronze Age began once copper was alloyed with tin to produce true bronze artefacts, and this took place around 2000 BC, when some Ballybeg flat axes and associated metalwork were produced. The period preceding this, in which Lough Ravel and most Ballybeg axes were produced, and which is known as the Copper Age or Chalcolithic, commenced about 2500 BC.

Bronze was used for the manufacture of both weapons and tools. Swords, axes, daggers, hatchets, halberds, awls, drinking utensils and horn-shaped trumpets are just some of the items that have been unearthed at Bronze Age sites. Irish craftsmen became particularly noted for the horn-shaped trumpet, which was made by the cire perdue, or lost wax, process.

Copper used in the manufacture of bronze was mined in Ireland, chiefly in the southwest of the island, while the tin was imported from Cornwall in Britain. The earliest known copper mine in these islands was located at Ross Island, at the Lakes of Killarney in County Kerry; mining and metalworking took place there between 2400 and 1800 BC. Another of Europe's best-preserved copper mines has been discovered at Mount Gabriel in County Cork, which was worked for several centuries in the middle of the second millennium.[14] Mines in Cork and Kerry are believed to have produced as much as 370 tonnes of copper during the Bronze Age. As only about 0.2% of this can be accounted for in excavated bronze artefacts, it is surmised that Ireland was a major exporter of copper during this period.

Ireland was also rich in native gold, and the Bronze Age saw the first extensive working of this precious metal by Irish craftsmen. More Bronze Age gold hoards have been discovered in Ireland than anywhere else in Europe. Irish gold ornaments have been found as far afield as Germany and Scandinavia. In the early stages of the Bronze Age these ornaments consisted of simple but finely decorated gold lunulae, a distinctively Irish type of object later made in Britain and the continent, and disks of thin gold sheet. Later the familiar thin twisted torc made its appearance; this was a collar consisting of a bar or ribbon of metal, twisted into a spiral. Gold earrings, sun disks, bracelets, clothes fasteners, large "gorgets" and in the Late Bronze Age, the distinctively Irish bullae amulets were also made in Ireland during the Bronze Age.

Smaller wedge tombs continued to be built throughout the Bronze Age, and while the previous tradition of large scale monument building was much reduced, existing earlier megalithic monuments continued in use in the form of secondary insertions of funerary and ritual artefacts. Towards the end of the Bronze Age the single-grave cist made its appearance. This consisted of a small rectangular stone chest, covered with a stone slab and buried a short distance below the surface. Numerous stone circles were also erected at this time, chiefly in Ulster and Munster.

During the Bronze Age, the climate of Ireland deteriorated and extensive deforestation took place. The population of Ireland at the end of the Bronze Age was probably in excess of 100,000, and may have been as high as 200,000. It is possible that it was not much greater than it had been at the height of the Neolithic. In Ireland the Bronze Age lasted until c. 500BC, later than the continent and also Britain.[15]

Iron Age (500 BC – AD 400)

Tribes of Ireland according to

Ptolemy's Geographia (written c. 150 AD).[16]

The Irish Iron Age began around 500 BC and continued until the Christian era in Ireland, which brought some written records and therefore the end of prehistoric Ireland. This is still often seen as the beginning of the arrival of the Celts (i.e. speakers of the Proto-Celtic language) and thus Indo-European speakers, to the island, though it is debatable to what extent, if any, the likely Indo-European speaking bearers of the Bell Beaker culture had colonized the island during the earlier stage of the Bronze Age.[17] The Iron Age includes the period in which the Romans ruled the neighbouring island of Britain. Roman interest in the area led to some of the earliest written evidence about Ireland. The names of its tribes were recorded by the geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD.

The Celtic languages of Britain and Ireland, also known as Insular Celtic, can be divided into two groups, Goidelic and Brittonic. When primary written records of Celtic first appear in about the fifth century, Gaelic or Goidelic, in the form of Primitive Irish, is found in Ireland, while Brittonic, in the form of Common Brittonic, is found in Britain.

The recorded tribes of Ireland included at least three with names identical or similar to British or Gaulish tribes: the Brigantes (also the name of the largest tribe in northern and midland Britain), the Manapii (possibly the same people as the Menapii, a Belgic tribe of northern Gaul) and the Coriondi (a name similar to that of Corinion, later Cirencester and the Corionototae of northern Britain).

The late Iron Age saw sizeable changes in human activity. Thomas Charles-Edwards coined the phrase "Irish Dark Age" to refer to a period of apparent economic and cultural stagnation in late prehistoric Ireland, lasting from c. 100 BC to c. AD 300.[18] Pollen data extracted from Irish bogs indicate that "the impact of human activity upon the flora around the bogs from which the pollen came was less between c. 200 BC and c. AD 300 than either before or after."[19] The third and fourth centuries saw a rapid recovery.[19] The reasons for the decline and recovery are uncertain, but it has been suggested that recovery may be linked to the purported "Golden Age" of Roman Britain in the third and fourth centuries. The archaeological evidence for trade with, or raids on, Roman Britain is strongest in northern Leinster, centred on modern County Dublin, followed by the coast of County Antrim, with lesser concentrations in the Rosses on the north coast of County Donegal and around Carlingford Lough.[20] Inhumation burials may also have spread from Roman Britain, and had become common in Ireland by the fourth and fifth centuries.[21]

Examples from Iron Age Ireland of La Tène style, the term for Iron Age Celtic art are very few, to a "puzzling" extent, although some of these are of very high quality, such as a number of scabbards from Ulster and the Petrie Crown, apparently dating to the 2nd century AD, well after Celtic art elsewhere had been subsumed into Gallo-Roman art and its British equivalent. Despite this it was in Ireland that the style seemed to revive in the early Christian period, to form the Insular art of the Book of Kells and other well-known masterpieces, perhaps under influence from Late Roman and post-Roman Romano-British styles. The 1st century BC Broighter Gold hoard, from Ulster, includes a small model boat, a spectacular torc with relief decoration influenced by classical style, and other gold jewellery probably imported from the Roman world, perhaps as far away as Alexandria.[22]

It was also during this time that some protohistoric records begin to appear.

References

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the British Isles |

|

| Prehistoric period |

| Classical period |

| Medieval period |

| Early modern period |

| Late modern period |

| By region |

|

|

- ↑ Clark, Peter U.; Dyke, Arthur S.; Shakun, Jeremy D.; Carlson, Anders E.; Clark, Jorie; Wohlfarth, Barbara; Mitrovica, Jerry X.; Hostetler, Steven W.; McCabe, A. Marshall (2009). "The Last Glacial Maximum". Science. 325: 710–714. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..710C. doi:10.1126/science.1172873. PMID 19661421.

- ↑ Stephens, Nicholas; Herries Davies, G. L. (1978). Ireland: The geomorphology of the British Isles. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-84640-8.

- 1 2 Edwards, Robin & al. "The Island of Ireland: Drowning the Myth of an Irish Land-bridge?" Accessed 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Cunliffe, 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ K. Lambeck, P. Johnston, C. Smither, K. Fleming and Y. Yokoyama, Late Pleistocene and Holocene sea-level change, Annual Report of the Research School of Earth Sciences, ANU College of Physical & Mathematical Sciences, Canberra, 1995.

- ↑ BBC (21 March 2016). "Earliest evidence of humans in Ireland". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Owen, James (13 March 2008). "Snakeless in Ireland: Blame the Ice Age, Not St. Patrick". National Geographic. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Tanabe, Susumu; Nekanishi, Toshimichi; Yasui, Satoshi (14 October 2010). "Relative sea-level change in and around the Younger Dryas inferred from late Quaternary incised valley fills along the Japan sea". Quaternary Science Reviews. pp. 3956–3971. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- 1 2 Driscoll, K. The Early Prehistory in the West of Ireland: Investigations into the Social Archaeology of the Mesolithic, West of the Shannon, Ireland (2006).

- ↑ Blood of the Irish.

- 1 2 "Kerry red deer ancestry traced to population introduced to Ireland by ancient peoples over 5,000 years ago". Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Michael Herity and George Eogan, Ireland in Prehistory (1996), p.114; M.J. O'Kelly, Bronze-age Ireland, in A New History of Ireland, vol 1: Prehistoric and early Ireland, edited by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (Royal Irish Academy 2005).

- ↑ J.X.W.P. Corcoram, "The origin of the Celts", in Nora Chadwick, The Celts (1970); David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world (2007).

- ↑ Michael Herity and George Eogan, Ireland in Prehistory (1996), pp.115–6.

- ↑ Ó Cróinín, p. lx.

- ↑ After Duffy (ed.), Atlas of Irish History, p. 15.

- ↑ A New History of Ireland, Volume I: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (Editor).

- ↑ Thomas Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, Cambridge, 2000, p. 145.

- 1 2 Charles-Edwards, p. 148.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, map 8.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Ó Cróinín, p. lx ("puzzling"), 137–152.

Bibliography

- Dardis GF (1986). "Late Pleistocene glacial lakes in South-central Ulster, Northern Ireland". Ir. J. Earth Sci. 7: 133–144.

- Barry, T. (ed.) A History of Settlement in Ireland. (2000) Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18208-5.

- Bradley, R. The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. (2007) Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84811-3.

- Coffey, G. Bronze Age in Ireland (1913).

- Driscoll, K. The Early Prehistory in the West of Ireland: Investigations into the Social Archaeology of the Mesolithic, West of the Shannon, Ireland (2006).

- Flanagan L. Ancient Ireland. Life before the Celts. (1998). ISBN 0-312-21881-8

- Herity, M. and G. Eogan. Ireland in Prehistory. (1996) Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04889-3

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí, ed. (2008). A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and early Ireland, (Volume 1 series), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-922665-2.

- Thompson, T. Ireland’s Pre-Celtic Archaeological and Anthropological Heritage. (2006) Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-5880-8.

- Waddell, J., The Celticization of the West: an Irish Perspective, in C. Chevillot and A. Coffyn (eds), L' Age du Bronze Atlantique. Actes du 1er Colloque de Beynac, Beynac (1991), 349–366.

- Waddell, J.,The Question of the Celticization of Ireland, Emania No. 9 (1991), 5–16.

- Waddell, J., 'Celts, Celticisation and the Irish Bronze Age', in J. Waddell and E. Shee Twohig (eds.), Ireland in the Bronze Age. Proceedings of the Dublin Conference, April 1995, 158–169.

Archaeology

- Arias, J. World Prehistory 13 (1999):403–464.The Origins of the Neolithic Along the Atlantic Coast of Continental Europe: A Survey.

- Bamforth and Woodman, Oxford J. of Arch. 23 (2004): 21–44. Tool hoards and Neolithic use of the landscape in north-eastern Ireland.

- Clark (1970) Beaker Pottery of Great Britain and Ireland of the Gulbenkain Archaeological Series, Cambridge University Press.

- Waddell, John (1998). The prehistoric archaeology of Ireland. Galway: Galway University Press. hdl:10379/1357.

Genetics

- McEnvoy; et al. (2004). "The Longue Durée of Genetic Ancestry: Multiple Genetic Marker Systems and Celtic Origins on the Atlantic Facade of Europe". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75: 693–704. doi:10.1086/424697. PMC 1182057

. PMID 15309688.

. PMID 15309688. - Finch; et al. (1997). "Distribution of HLA-A, B and DR genes and haplotypes in the Irish population". Exp. Clin. Immunogenet. 14: 250–263. PMID 9523161.

- Williams; et al. (2004). "High resolution HLA-DRB1 identification of a caucasian population". Hum. Immunology. 65: 66–77. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2003.10.004. PMID 14700598.

External links

- Ask about Ireland, Flora and fauna

- The Flandrian: the case for an interglacial cycle

- Ireland's history in maps : Ancient Ireland

- Dairying Pioneers: Milk ran deep in prehistoric England

- Postcards of the Prehistoric Monuments of Ireland

- John Waddell's publications on prehistory of Ireland

- Treasures of early Irish art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D., an exhibition catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- Prehistoric Waterford

- Brú na Bóinne/ Newgrange website