Price equation examples

In the theory of evolution and natural selection, the Price equation expresses certain relationships between a number of statistical measures on parent and child populations. Without training in the understanding of these measures, the meaning of Price equation is rather opaque. For the less experienced person, simple and particular examples are vital to gaining an intuitive understanding of these statistical measures as they apply to populations, and the relationship between them as expressed in the Price equation.

Example: Evolution of sight

As an example of the simple Price equation, consider a model for the evolution of sight. Suppose zi is a real number measuring the visual acuity of an organism. An organism with a higher zi will have better sight than one with a lower value of zi. Let us say that the fitness of such an organism is wi=zi which means the more sighted it is, the fitter it is, that is, the more children it will produce. Beginning with the following description of a parent population composed of 3 types: (i = 0,1,2) with sightedness values zi = 3,2,1:

i 0 1 2 ni 10 20 30 zi 3 2 1

Using Equation (4), the child population (assuming the character zi doesn't change; that is, zi = zi')

i 0 1 2 ni 30 40 30 zi 3 2 1

We would like to know how much average visual acuity has increased or decreased in the population. From Equation (3), the average sightedness of the parent population is z = 5/3. The average sightedness of the child population is z' = 2, so that the change in average sightedness is:

which indicates that the trait of sightedness is increasing in the population. Applying the Price equation we have (since z′i= zi):

Example: Evolution of sickle cell anemia

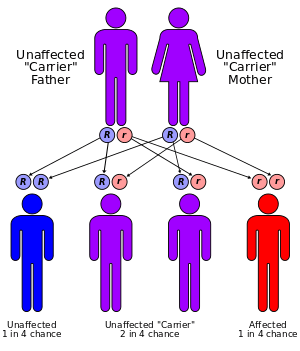

As an example of dynamical sufficiency, consider the case of sickle cell anemia. Each person has two sets of genes, one set inherited from the father, one from the mother. Sickle cell anemia is a blood disorder which occurs when a particular pair of genes both carry the 'sickle-cell trait'. The reason that the sickle-cell gene has not been eliminated from the human population by selection is because when there is only one of the pair of genes carrying the sickle-cell trait, that individual (a "carrier") is highly resistant to malaria, while a person who has neither gene carrying the sickle-cell trait will be susceptible to malaria. Let's see what the Price equation has to say about this.

Let zi=i be the number of sickle-cell genes that organisms of type i have so that zi = 0 or 1 or 2. Assume the population sexually reproduces and matings are random between type 0 and 1, so that the number of 0–1 matings is n0n1/(n0+n1) and the number of i–i matings is n2i/[2(n0+n1)] where i = 0 or 1. Suppose also that each gene has a 1/2 chance of being passed to any given child and that the initial population is ni=[n0,n1,n2]. If b is the birth rate, then after reproduction there will be

- type 0 children (unaffected)

- type 1 children (carriers)

- type 2 children (affected)

Suppose a fraction a of type 0 reproduce, the loss being due to malaria. Suppose all of type 1 reproduce, since they are resistant to malaria, while none of the type 2 reproduce, since they all have sickle-cell anemia. The fitness coefficients are then:

To find the concentration n1 of carriers in the population at equilibrium, with the equilibrium condition of Δ z=0, the simple Price equation is used:

where f=n1/n0. At equilibrium then, assuming f is not zero:

In other words, the ratio of carriers to non-carriers will be equal to the above constant non-zero value. In the absence of malaria, a=1 and f=0 so that the sickle-cell gene is eliminated from the gene pool. For any presence of malaria, a will be smaller than unity and the sickle-cell gene will persist.

The situation has been effectively determined for the infinite (equilibrium) generation. This means that there is dynamical sufficiency with respect to the Price equation, and that there is an equation relating higher moments to lower moments. For example, for the second moments:

Example: sex ratios

In a 2-sex species or deme with sexes 1 and 2 where , , is the relative frequency of sex 1. Since all individuals have one parent of each sex, the fitness of each sex is proportional to the number of the other sex. Consider proportionality constants and such that and . Under this scenario, a is the number of children a male would have if there he were the only male and unlimited number of females, while b is the number of children a female would have if she were the only female and unlimited number of males. This gives and , so . Hence, so that .

Under another scenario, every woman has a maximum number of children () so that children are created per generation, and every male is responsible for an equal number of children so that where and are the total number of females and males respectively. In this case, the sex ratio stabilizes at .

Example: Evolution of mutability

Suppose there is an environment containing two kinds of food. Let α be the amount of the first kind of food and β be the amount of the second kind. Suppose an organism has a single allele which allows it to utilize a particular food. The allele has four gene forms: A0, Am, B0, and Bm. If an organism's single food gene is of the A type, then the organism can utilize A-food only, and its survival is proportional to α. Likewise, if an organism's single food gene is of the B type, then the organism can utilize B-food only, and its survival is proportional to β. A0 and Am are both A-alleles, but organisms with the A0 gene produce offspring with A0-genes only, while organisms with the Am gene produce, among their n offspring, (n−3m) offspring with the Am gene, and m organisms of the remaining three gene types. Likewise, B0 and Bm are both B-alleles, but organisms with the B0 gene produce offspring with B0-genes only, while organisms with the Bm gene produce (n−3m) offspring with the Bm gene, and m organisms of the remaining three gene types.

Let i=0,1,2,3 be the indices associated with the A0, Am, B0, and Bm genes respectively. Let wij be the number of viable type-j organisms produced per type-i organism. The wij matrix is: (with i denoting rows and j denoting columns)

Mutators are at a disadvantage when the food supplies α and β are constant. They lose every generation compared to the non-mutating genes. But when the food supply varies, even though the mutators lose relative to an A or B non-mutator, they may lose less than them over the long run because, for example, an A type loses a lot when α is low. In this way, "purposeful" mutation may be selected for. This may explain the redundancy in the genetic code, in which some amino acids are encoded by more than one codon in the DNA. Although the codons produce the same amino acids, they have an effect on the mutability of the DNA, which may be selected for or against under certain conditions.

With the introduction of mutability, the question of identity versus lineage arises. Is fitness measured by the number of children an individual has, regardless of the children's genetic makeup, or is fitness the child/parent ratio of a particular genotype?. Fitness is itself a characteristic, and as a result, the Price equation will handle both.

Suppose we want to examine the evolution of mutator genes. Define the z-score as:

in other words, 0 for non-mutator genes, 1 for mutator genes. There are two cases:

Example: Evolution of altruism

To study the evolution of a genetic predisposition to altruism, altruism will be defined as the genetic predisposition to behavior which decreases individual fitness while increasing the average fitness of the group to which the individual belongs. First specifying a simple model, which will only require the simple Price equation. Specify a fitness wi by a model equation:

where zi is a measure of altruism, the azi term is the decrease in fitness of an individual due to altruism towards the group and bz is the increase in fitness of an individual due to the altruism of the group towards an individual. Assume that a and b are both greater than zero. From the Price equation:

where var(zi) is the variance of zi which is just the covariance of zi with itself:

It can be seen that, by this model, in order for altruism to persist it must be uniform throughout the group. If there are two altruist types the average altruism of the group will decrease, the more altruistic will lose out to the less altruistic.

Now assuming a hierarchy of groups which will require the full Price equation. The population will be divided into groups, labelled with index i and then each group will have a set of subgroups labelled by index j. Individuals will thus be identified by two indices, i and j, specifying which group and subgroup they belong to. nij will specify the number of individuals of type ij. Let zij be the degree of altruism expressed by individual j of group i towards the members of group i. Let's specify the fitness wij by a model equation:

The a zij term is the fitness the organism loses by being altruistic and is proportional to the degree of altruism zij that it expresses towards members of its own group. The b zi term is the fitness that the organism gains from the altruism of the members of its group, and is proportional to the average altruism zi expressed by the group towards its members. Again, in studying altruistic (rather than spiteful) behavior, it is expected that a and b are positive numbers. Note that the above behavior is altruistic only when azij >bzi. Defining the group averages:

and global averages:

It can be seen that since the zi and zi are now averages over a particular group, and since these groups are subject to selection, the value of Δzi = z′i−zi will not necessarily be zero, and the full Price equation will be needed.

In this case, the first term isolates the advantage to each group conferred by having altruistic members. The second term isolates the loss of altruistic members from their group due to their altruistic behavior. The second term will be negative. In other words, there will be an average loss of altruism due to the in-group loss of altruists, assuming that the altruism is not uniform across the group. The first term is:

In other words, for b>a there may be a positive contribution to the average altruism as a result of a group growing due to its high number of altruists and this growth can offset in-group losses, especially if the variance of the in-group altruism is low. In order for this effect to be significant, there must be a spread in the average altruism of the groups.