Gondwana

|

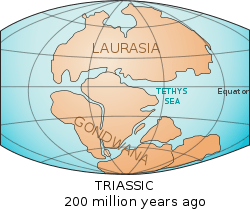

Map of Pangaea with Laurasia and Gondwana. 200 mya | |

| Historical continent | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 510 Mya |

| Type | Geological supercontinent |

| Today part of |

Africa North America South America Australia India Arabia Antarctica Balkans |

| Smaller continents |

Atlantica India Australia Antarctica Zealandia |

| Tectonic plate |

African Plate Antarctic Plate Indo-Australian Plate South American Plate |

In paleogeography, Gondwana (pronunciation: /ɡɒndˈwɑːnə/),[1][2] also Gondwanaland, is the name given to an ancient supercontinent. It is believed to have sutured between about 570 and 510 million years ago (Mya), joining East Gondwana to West Gondwana. Gondwana formed prior to Pangaea, and later became part of it.[3]

Around 300 Mya Gondwana and Laurasia joined together to form the supercontinent Pangaea, which existed until approximately 200-180 Mya. Gondwana then separated from Laurasia (the mid-Mesozoic era) in the breakup of Pangaea, drifting farther south after the split.[4] Gondwana itself then also broke apart.

Gondwana included most of the landmasses in today's Southern Hemisphere, including Antarctica, South America, Africa, Madagascar, and the Australian continent, as well as the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian Subcontinent, which have now moved entirely into the Northern Hemisphere.

The continent of Gondwana was named by Austrian scientist Eduard Suess, after the Gondwana region of central northern India which is derived from Sanskrit for "forest of the Gonds". The name had been previously used in a geological context, first by H.B. Medlicott in 1872.[5] from which the Gondwana sedimentary sequences (Permian-Triassic) are also described.

The adjective "Gondwanan" is in common use in biogeography when referring to patterns of distribution of living organisms, typically when the organisms are restricted to two or more of the now-discontinuous regions that were once part of Gondwana, including the Antarctic flora. For example, the Proteaceae family of plants known only from southern South America, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand is considered to have a "Gondwanan distribution". This pattern is often considered to indicate an archaic, or relict, lineage.

Formation

The assembly of Gondwana was a protracted process. Several orogenies led to its final amalgamation 550–500 Mya at the end of the Ediacaran, and into the Cambrian.[3] These include the Brasiliano Orogeny, the East African Orogeny, the Malagasy Orogeny, and the Kuunga Orogeny. The final stages of Gondwanan assembly overlapped with the opening of the Iapetus Ocean between Laurentia and western Gondwana. During this interval, the Cambrian explosion occurred.

Gondwana was formed from the following earlier continents and microcontinents, among others, colliding in the following orogenies:

- Azania: much of central Madagascar, the Horn of Africa and parts of Yemen and Arabia (Named by Collins and Pisarevsky (2005): "Azania" was a Greek name for the East African coast.)

- The Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block of central Africa;

- Neoproterozoic India: India, the Antongil Block in far eastern Madagascar, the Seychelles, and the Napier and Rayner Complexes in East Antarctica

- The Australia/Mawson continent: Australia west of Adelaide and a large extension into East Antarctica

- Other blocks which helped to form Argentina and some surrounding regions, including a piece transferred from Laurentia when the west edge of Gondwana scraped against southeast Laurentia in the Ordovician.[6][7] This is the Famatinian block (named after Famatina in northwest Argentina) and it formerly continued the line of the Appalachians southwards.[8]

One of the major sites of Gondwanan amalgamation was the East African Orogeny (Stern, 1994), where these two major orogenies are superimposed. The East African Orogeny at about 650–630 Mya affected a large part of Arabia, north-eastern Africa, East Africa, and Madagascar. Collins and Windley (2002) propose that in this orogeny, Azania collided with the Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block.[9]

The later Malagasy orogeny at about 550–515 Mya affected Madagascar, eastern East Africa and southern India. In it, Neoproterozoic India collided with the already combined Azania and Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block, suturing along the Mozambique Belt.[10]

At the same time, in the Kunga Orogeny Neoproterozoic India collided with the Australia/Mawson continent.

Pangaea

Other large continental masses, including the core cratons of North America (the Canadian Shield or Laurentia), Europe (Baltica), and Siberia, were added over time to form the supercontinent Pangaea by Permian time. When Pangaea broke up (mostly during the Jurassic), two large masses, Gondwana and Laurasia, were formed.

The reformed Gondwanan continent was not precisely the same as that which had existed before Pangaea formed; for example, most of Florida and southern Georgia and Alabama is underlain by rocks that were originally part of Gondwana, but that were left attached to North America when Pangaea broke apart.[11]

Climate

During the late Paleozoic, Gondwana extended from a point at or near the South Pole to near the Equator. Across much of Gondwana, the climate was mild. During the Mesozoic, the world was on average considerably warmer than it is today. Gondwana was then host to a huge variety of flora and fauna for many millions of years. The laurel forest of Australia, New Caledonia, and New Zealand have a number of other related species of the laurissilva de Valdivia, through the connection of the Antarctic flora as gymnosperms and deciduous angiosperm Nothofagus. Corynocarpus laevigatus is called the bay of New Zealand, Laurelia novae-zelandiae belongs to the same genus Laurelia. The sempervirens tree niaouli grows in Australia, New Caledonia, and New Zealand.

New Caledonia and New Zealand ecoregions became separated from Australia by continental drift 85 million years ago. The islands still retain plants that originated in Gondwana and spread to the Southern Hemisphere continents later. However, strong evidence exists of glaciation during the Carboniferous to Permian time, especially in South Africa.

Breakup

Mesozoic

Gondwana began to break up in the early Jurassic (about 184 Mya)[13] accompanied by massive eruptions of basalt lava, as East Gondwana, comprising Antarctica, Madagascar, India, and Australia, began to separate from Africa. South America began to drift slowly westward from Africa as the South Atlantic Ocean opened, beginning about 130 Mya during the Early Cretaceous, and resulting in open marine conditions by 110 Mya. East Gondwana then began to separate about 120 Mya when India began to move northward.

The Madagascar block, and a narrow remnant microcontinent presently occupied by the Seychelles Islands, were broken off India; elements of this breakup nearly coincide with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The India–Madagascar–Seychelles separations appear to coincide with the eruption of the Deccan basalts, whose eruption site may survive as the Réunion hotspot.

Australia began to separate from Antarctica perhaps 80 Mya (Late Cretaceous), but sea-floor spreading between them became most active about 40 Mya during the Eocene epoch of the Paleogene Period.

New Zealand probably separated from Antarctica between 130 and 85 Mya.

Cenozoic

As the age of mammals commenced, the continent of Australia-New Guinea began gradually to separate and move north (55 Mya), rotating about its axis to begin with, and thus retaining some connection with the remainder of Gondwana for about 10 million years.

About 45 Mya, the Indian Plate collided with Asia, buckling the crust and forming the Himalayas. At about the same time, the southernmost part of Australia (modern Tasmania) finally separated from Antarctica, letting ocean currents flow between the two continents for the first time. Antarctica became cooler and Australia became drier because ocean currents circling Antarctica were no longer directed around northern Australia into the subtropics.

The separation of South America from West Antarctica some time during the Oligocene, perhaps 30 Mya, also caused climate changes. Immediately before this separation, South America and East Antarctica were not connected directly. However, the many microplates of the Antarctic Peninsula remained near southern South America, acting as "stepping stones" and allowing continued biological interchange and stopped oceanic current circulation. When the Drake Passage opened, a barrier was no longer present to force the cold waters of the Southern Ocean to be exchanged with warmer tropical water. Instead, a cold circumpolar current developed and Antarctica became what it is today: a frigid continent that locks up much of the world's fresh water as ice. Sea temperatures dropped by almost 10°C, and the global climate became much colder.

By about 15 Mya, the collision between New Guinea (on the leading edge of the Australian Plate) and the southwestern part of the Pacific Plate pushed up the New Guinea Highlands, causing a rain shadow effect which drastically changed weather patterns in Australia, drying it out.

Later, South America was connected to North America via the Isthmus of Panama, cutting off a circulation of warm water and thereby making the Arctic colder, as well as allowing the Great American Interchange.

The Red Sea and East African Rift are modern examples of continental rifting.

See also

- Continental drift, the movement of the Earth's continents relative to each other

- Geology of the Australasian ecozone

- Gondwana Rainforests of Australia

- The Great Escarpment of Southern Africa

- Plate tectonics, a theory which describes the large-scale motions of Earth's lithosphere

- South Polar dinosaurs, which proliferated during the Early Cretaceous (145–100 Mya) while Australia was still linked to Antarctica to form East Gondwana

- Tarkine wilderness

References

- ↑ "gondwana". Dictionary.com. Lexico Publishing Group. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ "Gondwanaland". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- 1 2 Buchan, Craig (November 7–10, 2004). Paper No. 207-8 - Linking Subduction Initiation, Accretionary Orogenesis And Supercontinent Assembly. 2004 Denver Annual Meeting. Geological Society of America. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ Houseman, Greg. "Dispersal of Gondwanaland". University of Leeds. Retrieved 21 Oct 2008.

- ↑ Eduard Suess, Das Antlitz der Erde (The Face of the Earth), vol. 1 (Leipzig, Germany: G. Freytag, 1885), page 768. From p. 768: "Wir nennen es Gondwána-Land, nach der gemeinsamen alten Gondwána-Flora, … " (We name it Gondwána-Land, after the common ancient flora of Gondwána … )

- ↑ Rapalini, AE (2001). The Assembly of Southern South America in the Late Proterozoic and Paleozoic: Some Paleomagnetic Clues. Spring Meeting 2001. American Geophysical Union. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ Rapalini, AE (1998). "Syntectonic magnetization of the mid-Palaeozoic Sierra Grande Formation: further constraints on the tectonic evolution of Patagonia". Journal of the Geological Society. 155 (1): 105–114. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.155.1.0105.

- ↑ http://sp.lyellcollection.org/content/142/1/219.abstract Laurentia-Gondwana collision: the origin of the Famatinian-Appalachian Orogenic Belt (a review)

- ↑ Collins, Alan S; Windley, Brian F (May 2002). "The Tectonic Evolution of Central and Northern Madagascar and Its Place in the Final Assembly of Gondwana". The Journal of Geology. 110 (3): 325–339. Bibcode:2002JG....110..325C. doi:10.1086/339535.

- ↑ Grantham, G.H.; Maboko, M.; Eglington, B.M. (2003). "A review of the evolution of the Mozambique Belt and implications for the amalgamation and dispersal of Rodinia and Gondwana". Proterozoic East Gondwana: supercontinent assembly and breakup. Geological Society. pp. 417–418. ISBN 1-86239-125-4.

- ↑ "Gondwana Remnants In Alabama And Georgia: Uchee Is An 'Exotic' Peri-Gondwanan Arc Terrane, Not Part Of Laurentia". ScienceDaily. February 4, 2008. Retrieved October 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ H.M. Li and Z.K. Zhou (2007) Fossil nothofagaceous leaves from the Eocene of western Antarctica and their bearing on the origin, dispersal and systematics of Nothofagus. Science in China. 50(10): 1525-1535.

- ↑ Encarnación, John; Fleming, Thomas H.; Elliot, David H.; Eales, Hugh V. (1996-06-01). "Synchronous emplacement of Ferrar and Karoo dolerites and the early breakup of Gondwana". Geology. 24 (6): 535–538. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1996)0242.3.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

Further reading

- Cattermole, Peter John (2000). Building Planet Earth: Five Billion Years of Earth History. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58278-0. OCLC 317422973.

- Collins, Alan S; Pisarevsky, Sergei A (August 2005). "Amalgamating eastern Gondwana: The evolution of the Circum-Indian Orogens". Earth-Science Reviews. 71 (3–4): 229–270. Bibcode:2005ESRv...71..229.. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.02.004.

- Cowen, Richard (2000). History of Life (3rd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-04444-3. OCLC 41572551.

- Encarnacion, J; Fleming, Thomas H.; Elliot, David H.; Eales, Hugh V. (1996). "Synchronous emplacement of Ferrar and Karoo dolerites and the early break-up of Gondwana". Geology. 24 (6): 535–538. Bibcode:1996Geo....24..535E. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024<0535:SEOFAK>2.3.CO;2.

- Lowrie, William (1997). Fundamentals of Geophysics. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46164-1. OCLC 35651121. Also ISBN 978-0-521-46728-5.

- Meert, JG (2003-02-06). "A synopsis of events related to the assembly of eastern Gondwana". Tectonophysics. 363 (1): 1–40. Bibcode:2003Tectp.362....1M. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(02)00629-7.

- Scheffler, K; Hoernes, S; Schwark, L (July 2003). "Global changes during Carboniferous–Permian glaciation of Gondwana: Linking polar and equatorial climate evolution by geochemical proxies". Geology. 33 (7): 605–608. Bibcode:2003Geo....31..605S. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0605:GCDCGO>2.0.CO;2.

- Stern, RJ (May 1994). "ARC Assembly and Continental Collision in the Neoproterozoic East African Orogen: Implications for the Consolidation of Gondwanaland". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 22: 319–351. Bibcode:1994AREPS..22..319S. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.22.050194.001535.

External links

- Animation showing the dispersal of Gondwanaland

- Graphical subjects dealing with Tectonics and Paleontology

- Gondwana Reconstruction and Dispersion

- The Gondwana Map Project

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)