R-Phase

The R-phase is a phase found in nitinol. It is a martensitic phase in nature, but is not the martensite that is responsible for the shape memory and superelastic effect. When one uses the word martensite in connection with nitinol, one is invariably referring to the B19' monoclinic martensite phase, not the R-phase. The R-phase competes with martensite, often completely absent, and often appearing during cooling before martensite then giving way to martensite upon further cooling. Similarly, it can be observed during heating prior to reversion to austenite, or may be completely absent. The R-phase to austenite transformation (A-R) is reversible, with a very small hysteresis (typically 2-5 degrees C). It also exhibits a very small shape memory effect, and within a very narrow temperature range, superelasticity. The R-phase transformation (from austenite) occurs between 20 and 40 degrees C in most binary nitinol alloys.

The R-phase was observed during the 1970s but generally was not correctly identified until Ling and Kaplow's landmark paper of 1981.[1] The crystallography and thermodynamics of the R-phase are now well understood, but it still creates many complexities in device engineering, leading to the well-worn phrase, "It must be the R-phase" whenever a device fails to perform as expected.

Crystallographic structure and transformation

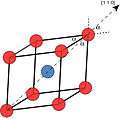

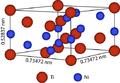

The R-phase is essentially a rhombohedral distortion of the cubic austenite phase. Figure 1 shows the general structure, though there are shifts in atomic position that repeat after every three austenitic cells. Thus the actual unit cell of the actual R-phase structure is shown in Figure 2.[2] The R-phase can be easily detected via x-ray diffraction or neutron diffraction, most clearly evidenced by a splitting of the (1 1 0) austenitic peak.

While the R-phase transformation is a first order transformation and the R-phase is distinct and separate from martensite and austenite, it is followed by a second order transformation: a gradual shrinking of the rhombohedral angle and concomitant increased transformational strain. By suppressing martensite formation and allowing the second order transformation to continue, the transformational strain can be maximized. Such measures have shown memory and superelastic effects of nearly 1%.[3] In commercially available superelastic alloys, however, the R-phase transformational strain is only 0.25 to 0.50 percent.

There are three ways Nitinol can transform between the austenite and martensite phases:

- Direct transformation, with no evidence of R-phase during the forward or reverse transformation (cooling or heating), occurs in titanium-rich alloys and fully annealed conditions.

- The "symmetric R-phase transformation" occurs when the R-phase intervenes between austenite and martensite on both heating and cooling (see Figure 3). Here, two peaks are observed on cooling, and two peaks upon heating, with the heating peaks much closer to one another due to the lower hysteresis of the A-R transformation.

- The "asymmetric R-phase transformation" is by far the more common transformational route (Figure 4). Here the R-phase occurs during cooling, but not upon heating, due to the large hysteresis of the austenite-martensite transformation—by the time one reaches a sufficiently high temperature to revert martensite, the R-phase is no longer more stable than austenite, and thus the martensite reverts directly to austenite.

The R-phase can be stress-induced as well as thermally-induced. The stress rate (Clausius–Clapeyron constant, ) is very large compared to the austenite–martensite transformation (very large stresses are required to drive the transformation).

-

Figure 1: The R-Phase distortion of the B2 austenitic structure

-

Figure 2: The trigonal representation of the R-phase

-

Figure 3: Free energy, strain, and calorimetry curves typical of the symmetric Austenite-R-Martensite transformation, in which R-phase is found during both cooling and heating.

-

Figure 4: Free energy, strain, and calorimetry curves typical of the asymmetric Austenite-R-Martensite transformation, in which R-phase is found only upon cooling.

Practical Implications

While an essentially hysteresis-free shape memory effect sounds exciting, the strains produced by the austenite-R transformation are too small for most applications. Because of the very small hysteresis, and the tremendous cyclic stability of the A-R transformation, some effort has been made to commercialize thermal actuators based on the effect.[4] Such applications have been of limited success at best. For most of Nitinol applications, the R-phase is an annoyance and engineers try to suppress its appearance. Some of the difficulties it induces are as follows:

- When austenite transforms to the R-phase, its energy is reduced and its propensity to transform to martensite is lessened, leading to a larger austenite-martensite hysteresis. This, in turn reduces actuator efficiency and superelastic energy storage capacity.

- Stress-strain curves of the austenite often show a slight inflection during loading, making elastic limits and yield stresses difficult to pinpoint

- While a 0.25% strain is too small to take advantage of, it is more than enough to cause stress relaxation in many interference-fit applications such as pipe couplings.

- A large amount of heat is given off when austenite transforms to the R-phase, and thus it gives rise to a well-defined differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) peak. This makes DSC curves difficult to interpret if one is not careful: the R-phase peak is often mistaken for a martensite peak, and errors are often made in determining transformation temperatures.

- While the electrical resistivity of austenite and martensite are similar, the R-phase has a very high resistance. This makes using electrical resistance all but useless in determining the transformation temperatures of Nitinol.

The R-phase becomes more pronounced through additions of iron, cobalt, and chromium, and is suppressed by additions of copper, platinum and palladium. Cold working and aging also tend to exaggerate the R-phase presence.

References

- ↑ Ling, H.C.; and Kaplow R. (1981), "Stress-Induced Shape Changes and Shape Memory in the R and Martensite Transformations in Equiatomic NiTi", Met. Trans., 12A: 2101 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help). - ↑ Otsuka, K.; and Ren X. (1999), "Recent developments in the research of shape memory alloys", Intermetallics, 7: 511, doi:10.1016/s0966-9795(98)00070-3 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help). - ↑ Proft, J.L.; and Duerig, T.W. (1987), "Yield Drop and Snap Action in a Warm Worked Ni-Ti-Fe Alloy", Proceedings of ICOMAT-86, Jap. Inst. of Metals: 742 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help). - ↑ Ohkata, I.; and Tamura H. (1997), Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc., 459: 345 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help).