Radium Girls

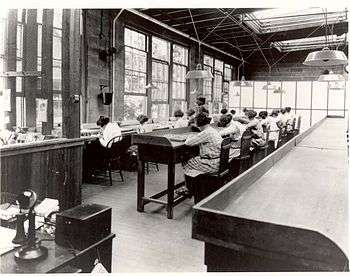

The Radium Girls were female factory workers who contracted radiation poisoning from painting watch dials with self-luminous paint at the United States Radium factory in Orange, New Jersey, around 1917. The women, who had been told the paint was harmless, ingested deadly amounts of radium by licking their paintbrushes to give them a fine point; some also painted their fingernails, face, and teeth with the glowing substance.

Five of the women challenged their employer in a case that established the right of individual workers who contract occupational diseases to sue their employers.

United States Radium Corporation

_advertisement%2C_1921%2C_retouched.png)

From 1917 to 1926, U.S. Radium Corporation, originally called the Radium Luminous Material Corporation, was engaged in the extraction and purification of radium from carnotite ore to produce luminous paints, which were marketed under the brand name "Undark". The ore was mined from the Paradox Valley in Colorado[1] and other "Undark mines" in Utah.[2] As a defense contractor, U.S. Radium was a major supplier of radioluminescent watches to the military. Their plant in Orange, New Jersey, employed more than a hundred workers, mainly women, to paint radium-lit watch faces and instruments, misleading them that it was safe.

Radiation exposure

The U.S. Radium Corporation hired approximately 70 women to perform various tasks including the handling of radium, while the owners and the scientists familiar with the effects of radium carefully avoided any exposure to it themselves; chemists at the plant used lead screens, masks and tongs.[3] U.S. Radium had distributed literature to the medical community describing the "injurious effects" of radium. In spite of this knowledge, a number of similar deaths had occurred by 1925, including the company's chief chemist, Dr Edwin E. Leman and several female workers. The similar circumstances of their deaths prompted investigations to be undertaken by Dr. Harrison Martland, County Physician of Newark.[4]

An estimated 4,000 workers were hired by corporations in the U.S. and Canada to paint watch faces with radium. They mixed glue, water and radium powder, and then used camel hair brushes to apply the glowing paint onto dials. The then-current rate of pay, for painting 250 dials a day, was about a penny and a half per dial (equivalent to $0.278 in 2015). The brushes would lose shape after a few strokes, so the U.S. Radium supervisors encouraged their workers to point the brushes with their lips, or use their tongues to keep them sharp. For fun, the Radium Girls painted their nails, teeth and faces with the deadly paint produced at the factory.[5] Many of the workers became sick. It is unknown how many died from exposure to radiation.

Radiation sickness

Many of the women later began to suffer from anemia, bone fractures and necrosis of the jaw, a condition now known as radium jaw. It is thought that the X-ray machines used by the medical investigators may have contributed to some of the sickened workers' ill-health by subjecting them to additional radiation. It turned out at least one of the examinations was a ruse, part of a campaign of disinformation started by the defense contractor.[3] U.S. Radium and other watch-dial companies rejected claims that the afflicted workers were suffering from exposure to radium. For some time, doctors, dentists, and researchers complied with requests from the companies not to release their data. At the urging of the companies, worker deaths were attributed by medical professionals to other causes; syphilis, a notorious sexually transmitted disease at the time, was often cited in attempts to smear the reputations of the women.[6]

The inventor of radium dial paint, Dr Sabin A. Von Sochocky died in November 1928, becoming the 16th known victim of poisoning by radium dial paint. He consistently denied that his invention had been the cause of the deaths of the Radium Girls.[7]

Significance

Litigation

The story of the abuse perpetrated against the workers is distinguished from most such cases by the fact that the ensuing litigation was covered widely by the media. Plant worker Grace Fryer decided to sue, but it took two years for her to find a lawyer willing to take on U.S. Radium. Even after the women found a lawyer, the slow-moving courts held out for months. At their first appearance in court on January 1928, two women were bedridden and none of them could raise their arms to take an oath. A total of five factory workers – Grace Fryer, Edna Hussman, Katherine Schaub, and sisters Quinta McDonald and Albina Larice – dubbed the Radium Girls, joined the suit.[8] The litigation and media sensation surrounding the case established legal precedents and triggered the enactment of regulations governing labor safety standards, including a baseline of "provable suffering".

Historical impact

The Radium Girls saga holds an important place in the history of both the field of health physics and the labor rights movement. The right of individual workers to sue for damages from corporations due to labor abuse was established as a result of the Radium Girls case. In the wake of the case, industrial safety standards were demonstrably enhanced for many decades.

The case was settled in the autumn of 1928, before the trial was deliberated by the jury, and the settlement for each of the Radium Girls was $10,000 (equivalent to $138,000 in 2015) and a $600 per year annuity (equivalent to $8,300 in 2015) while they lived, and all medical and legal expenses incurred would also be paid by the company.[9][10]

The lawsuit and resulting publicity was a factor in the establishment of occupational disease labor law.[11] Radium dial painters were instructed in proper safety precautions and provided with protective gear; in particular, they no longer shaped paint brushes by lip and avoided ingesting or breathing the paint. Radium paint was still used in dials as late as the 1960s.[12]

Scientific impact

Robley D. Evans made the first measurements of exhaled radon and radium excretion from a former dial painter in 1933. At MIT he gathered dependable body content measurements from 27 dial painters. This information was used in 1941 by the National Bureau of Standards to establish the tolerance level for radium of 0.1 μCi (3.7 kBq).

The Center for Human Radiobiology was established at Argonne National Laboratory in 1968. The primary purpose of the Center was providing medical examinations for living dial painters. The project also focused on collection of information and, in some cases, tissue samples from the radium dial painters. When the project ended in 1993, detailed information of 2,403 cases had been collected. This led to a book on the effects of radium on humans. The book suggests that radium-228 exposure is more harmful to health than exposure to radium-226. Radium-228 is more able to cause cancer of the bone as the shorter half life of the radon-220 product compared to radon-222 causes the daughter nuclides of radium-228 to deliver a greater dose of alpha radiation to the bones. It also considers the induction of a range of different forms of cancer as a result of internal exposure to radium and its daughter nuclides. The book used data from both radium dial painters, people who were exposed as a result of the use of radium containing medical products and other groups of people who have been exposed to radium.[13]

Literature and film

- The story is told from the point of view of the women in New Jersey and Illinois in Kate Moore's non-fiction book 'The Radium Girls' (2016, ISBN 1471153878)

- The story is told in Eleanor Swanson's poem Radium Girls, collected in A Thousand Bonds: Marie Curie and the Discovery of Radium (2003, ISBN 0-9671810-7-0)

- D. W. Gregory told the story of Grace Fryer in the play Radium Girls, which premiered in 2000 at the Playwrights Theatre in Madison, New Jersey.

- There is an elaborate reference to the story in the Kurt Vonnegut novel Jailbird (1979, ISBN 0-385-33390-0)

- Poet Lavinia Greenlaw has written on the subject in The Innocence of Radium (Night Photograph, 1994)

- Historian Claudia Clark wrote an account of the case and its wider historical implications: Radium Girls: Women and Industrial Health Reform, 1910–1935 (published 1997).

- Ross Mullner's book Deadly Glow: The Radium Dial Worker Tragedy describes many of the events (1999, ISBN 0-87553-245-4)

- The story is told by Jo Lawrence in her short animated film "Glow" (2007)

- The story is referenced in the 2006 film Pu-239

- The Michael A. Martone short story It's Time is told from the perspective of an unnamed Radium Girl

- A fictionalized version of the story was featured in the Spike TV show 1000 Ways to Die (#196)[14] and Science Channel's Dark Matters: Twisted But True

- Radium Halos: A Novel about the Radium Dial Painters a 2009 novel by Shelley Stout is historical fiction narrated by a sixty-five-year-old mental patient who worked at the factory when she was sixteen (ISBN 978-1448696222).

- Author Deborah Blum referenced the story in her 2010 book The Poisoner's Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York.

- The story is told in the American Experience episode The Poisoner's Handbook, based on Deborah Blum's book.

- Author Robert R. Johnson features a story on the radium girls in his book Romancing the Atom. (ISBN 978-0313392795) [15]

- The Case of the Living Dead Women, a website displaying scans of 180 pages of newspaper clippings about a similar incident, the Ottawa, Illinois Radium Dial Company litigation[16]

- The Radium Dial Company workers' story is dramatized in Melanie Marnich's stage play These Shining Lives.

- A fictionalized version of the story was featured in the 1937 short story "Letter to the Editor" by James H. Street, adapted into a 1937 film Nothing Sacred and a 1953 Broadway musical Hazel Flagg.

- The documentary "Radium City" depicts first hand accounts of some of the watch dial painters.[17]

See also

- Occupational disease

- Breaker boy

- Labor rights

- Labor history

- Labor law

- Susanne Antonetta

- Radioactive contamination

- Phossy jaw

- Nuclear labor issues

- Hiroshima maidens

References

- ↑ "Smithsonian displays ore containing radium, United States Radium Corporation (1921) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ↑ "Museums holding exhibits to explain uses of radium, United States Radium Corporation (1922) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- 1 2 http://www.damninteresting.com/?p=660

- ↑ "US Starts Probe of Radium Poison Deaths in Jersey, United States Radium Corporation (1925) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ↑ Grady, Denise (October 6, 1998). "A Glow in the Dark, and a Lesson in Scientific Peril". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ↑ Mullner, R. (1999). Deadly Glow: The Radium Dial Worker Tragedy. American Public Health Association. ISBN 9780875532455.

- ↑ "Dr S. von Sochocky death notice - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ↑ "Women radium victims offer selves for test while alive, United States Radium Corporation (1928) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ↑ Kovarik, Bill (2002). "The Radium Girls" (PDF). (originally published as chapter eight of Mass Media and Environmental Conflict). RUNet.edu. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- ↑ http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl

- ↑ "Mass Media & Environmental Conflict - Radium Girls". Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ Oliveira, Pedro (2012). The Elements: Periodic Table Reference. pediapress.com. p. 1192. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Rowland, R. E. (1994). Radium in Humans: A Review of U.S. Studies (PDF). Argonne, Illinois: Argonne National Laboratory.

- ↑ "Radium Girls". 1000 ways to die.

- ↑ Johnson, Robert R. (2012). Romancing the Atom. Praeger. p. 210. ISBN 978-0313392795.

- ↑ The Case of the Living Dead Women

- ↑ "'Radium City' Paints Incredible Horror Story of the Atomic Age".

External links

- University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey - 'University Libraries Special Collections: U.S. Radium Corporation, East Orange, NJ', Records, Catalog 1917-1940 (Revised, June, 2003)

- Undark and the Radium Girls, Alan Bellows, December 28, 2006, Damn Interesting

- Radium Girls, Eleanor Swanson. copy of original

- Poison Paintbrush, Time, June 4, 1928. "That the world may see streaks of light through the long hours of darkness, Orange, N. J., women hired themselves to the U. S. Radium Corporation."

- Radium Women, Time, August 11, 1930. "Five young New Jersey women who were poisoned while painting luminous watch dials for U. S. Radium Corp., two years ago heard doctors pronounce their doom: one year to live."

- Mae Keane, The Last 'Radium Girl,' Dies At 107, NPR