Ragnall mac Gofraid

| Ragnall mac Gofraid | |

|---|---|

| King of the Isles | |

.jpg) Ragnall's name as it appears on folio 35r of Oxford Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson B 489 (the Annals of Ulster).[1] | |

| Predecessor | Gofraid mac Arailt? |

| Died |

1004 or 1005 Munster |

| Issue | Echmarcach?, Cacht?, Amlaíb? |

| House | probably Uí Ímair |

| Father | Gofraid mac Arailt |

Ragnall mac Gofraid (died 1004/1005) was King of the Isles and likely a member of the Uí Ímair kindred.[note 1] He was a son of Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles. Ragnall and Gofraid flourished at a time when the Kingdom of the Isles seems to have suffered from Orcadian encroachment at the hands of Sigurðr Hlǫðvisson, Earl of Orkney. Gofraid died in 989. Although Ragnall is accorded the kingship upon his own death in 1004 or 1005, the succession after his father's death is uncertain.

During his career, Ragnall may have contended with Gilli, an apparent Hebridean rival who was closely aligned with Sigurðr. Another possible opponent of Ragnall may have been Sveinn Haraldsson, King of Denmark who attacked Mann in 955. This man is recorded to have been exiled from Scandinavia at one point in his career, and to have found shelter with a certain "rex Scothorum", a monarch that could refer to Ragnall himself. Whatever the case, Mann also fell prey to Æðelræd II, King of the English in 1000. Both military operations may have been the retaliation

The circumstances surrounding Ragnall's death in Munster are unknown. On one hand it is possible that he had been exiled from the Isles at the time of his demise. Another possibility is that he had—or was in the process of—forming an alliance with Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, King of Munster, a man who seems to have held an alliance with Ragnall's father. On possibility is that Ragnall sought assistance from Briain after having been forced from the Isles by Orcadian military might. A power vacuum resulting from Ragnall's demise may partly account from the remarkable English invasion of England by Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Alba.

At about the same time as Ragnall's death, Brian occupied the high kingship of Ireland, and there is evidence to suggest that the latter's authority stretched into the Irish Sea region and northern Britain. Not long afterwards, an apparent brother of Ragnall, Lagmann mac Gofraid, is attested on the Continent, a fact which might be evidence that this man had been ejected from the Isles by Brian. An apparent son Lagmann was slain in battle against Brian's forces in 1014. The lack of a suitable native candidate to reign in the Isles may have led to the region falling under the royal authority of the Norwegian Hákon Eiríksson. The latter's death in 1029 or 1030 may have likewise contributed to the rise Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles, a possible son of Ragnall. Other children of Ragnall could include Cacht ingen Ragnaill, and the father of Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill, King of Dublin.

King of the Isles

.png)

Ragnall was a son of Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles (died 989).[20] Ragnall belonged to the Meic Arailt, a family named after his paternal grandfather, Aralt.[21] The latter's identity is uncertain, although he may well have been a member of the Uí Ímair kindred.[22][note 2] From at least 972[24] to 989 Gofraid actively campaigned in the Irish Sea region,[25] after which the political cohesion of Kingdom of the Isles[26]—perhaps shaken by Orcadian encroachment in the 980s[27]—seems to have diminished.[28]

There is evidence to suggest that Sigurðr Hlǫðvisson, Earl of Orkney (died 1014) extended his authority from Orkney into the Isles in the late tenth- and early eleventh century.[29] According to various Scandinavian sources, Sigurðr oversaw numerous raids into the Isles during his career. For instance, the thirteenth-century Njáls saga states that one of Sigurðr's followers, Kári Sǫlmundarson, extracted taxes from the northern Hebrides, then controlled by a Hebridean earl named Gilli.[30] Also noted are additional assaults conducted by accomplices of Sigurðr throughout the Hebrides, Kintyre, Mann, and Anglesey.[31] The thirteenth-century Orkneyinga saga makes note of Sigurðr's raids into the Hebrides,[32] whilst the thirteenth-century Eyrbyggja saga states that his forces reached as far as Mann where he collected taxation.[33]

The extent of Gofraid's own authority in the Hebrides is unknown due to his apparent coexistence with Gilli, and to the uncertainty of Orcadian encroachment. Gofraid's successor is likewise uncertain.[36] On one hand, he may have been succeeded by Ragnall himself.[37] Although it is conceivable that either Gilli or Sigurðr capitalised on Gofraid's death, and extended their overlordship as far south as Mann, possible after-effects such as these are uncorroborated.[38] Although it is possible that Gilli controlled the Hebrides whilst Gofraid ruled Mann, the title accorded to the latter on his death could indicate otherwise.[39] If so, the chronology of Gilli's subordination to Sigurðr may actually date to the period after Ragnall's death in 1004/1005.[40] Little is certain of Ragnall's reign.[41] Certainly, he was accorded the kingship of the Isles by the time of his death,[42] and it is possible that he faced opposition from Sigurðr during his career.[43]

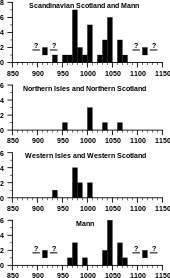

Njáls saga specifically states that the latter and his men overcame a king on Mann named Gofraid after which they plundered the Isles.[44] Whilst this royal figure may well refer to Ragnall's father,[45] another possibility is that source actually refers to Ragnall himself.[46] Contemporary Orcadian expansion may be perceptible in the evidence of the land-assessment system of ouncelands in the Hebrides and along the western coast of Scotland.[47] If Sigurðr's authority indeed stretched over the Isles in the last decades of the tenth century, such an intrusion could account for the numbers of silver hoards dating to this time.[48] The remarkable proportion of silver hoards from Mann and the Scandinavian regions of Scotland that date to about 1000 seem to reflect the wealth of Sigurðr's domain at about the apogee of his authority. The hoards from Argyll that date to this period could be indicative of conflict between Sigurðr and Ragnall.[49]

.jpg)

At some point in the decade following Gofraid's demise, Sveinn Haraldsson, King of Denmark (died 1014) was forced from his own realm. According to Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum by Adam of Bremen (died c. 1085), Sveinn fled to Æðelræd II, King of the English (died 1016), before he found shelter with an certain "rex Scothorum".[51] Whilst this unnamed monarch could be identical to the reigning Cináed mac Maíl Choluim, King of Alba (died 995),[52] the term Scoti can refer to the Irish just as well as the Scots.[53] Adam is otherwise known to have been less than well-informed of affairs in Britain, and it is possible that was confused as to the king's true identity.[54] For instance, Adam may well have referred to a Scottish, Irish,[55] Cumbrian, or Norse-Gaelic monarch.[56] In fact, Ragnall's position of power in the Irish Sea could well have led Adam to regard him as an Irish royal.[57] In 995, the "B" version of the eleventh–thirteenth-century Annales Cambriæ, the thirteenth/fourteenth-century Brenhinedd y Saesson, and the thirteenth/fourteenth-century Brut y Tywysogyon, report that Mann suffered an invasion from Sveinn.[58] One possibility is that this assault was directed at the Uí Ímair. Certainly, Ragnall does not appear to have achieved the same level of success as his father, whilst Sveinn's invasion coincided with a bitter struggle for Dublin between Ímar, King of Waterford (died 1000) and Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, King of Dublin (died 1042)[59]—strife amongst the Uí Ímair that was also capitalised upon by Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, King of Mide (died 1022) within the year.[60]

Death

.jpg)

In 1004[63] or 1005,[64] Ragnall died in Munster.[65] His death is recorded by the eleventh–fourteenth-century Annals of Inisfallen,[66] the fifteenth–sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster,[67] and the twelfth-century Chronicon Scotorum.[68] The circumstances surrounding Ragnall's demise are uncertain. One possibility is that he was attempting to take control of Limerick.[69] Another possibility is that he may have been exiled from the Isles,[70] which could account for the fact that no military engagement is associated with his obituaries.[71]

.jpg)

Alternately, the record of Ragnall's death in Munster could indicate that he was attempting form an alliance with Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, King of Munster (died 1014).[73] In 1004 or 1005, at about the time of Ragnall's death, Brian is styled imperator Scottorum ("emperor of the Scotti") by the ninth-century Book of Armagh.[74][note 3] This title may be evidence that Brian claimed authority outwith Ireland, and could indicate that he indeed came to an accommodation with Ragnall and some of the men of the Isles.[77] If so, such an aligned by Ragnall may have been undertaken in the context of countering the encroachment of Sigurðr's influence into the Isles.[78] Whether Ragnall was subdued by Brian or merely formed an alliance with him, a possible aftereffect of Brian's apparent extension into the Isles may have been Sveinn's campaigning in the region, a venture possibly undertaken in an effort to offset Brian's influence.[79]

.jpg)

There is evidence to suggest that Ragnall's family indeed held an alliance with Brian and his family.[81] In 974, for example, Gofraid's brother, Maccus (fl. 974), is recorded to have attacked the monastic site of Inis Cathaig, where Ímar, King of Limerick (died 977)[82]—an apparent foe of Brian's family[83]—was taken prisoner.[82] Explicit evidence of an alliance between Brian's family and the Meic Arailt is preserved by the Annals of Inisfallen which reports that the Meic Arailt rendezvoused with the sons of Brian's father at Waterford in 984, and exchanged hostages with them in an an apparent agreement pertaining to military cooperation between the parties.[84] As a result of this compact, Brian's family seems to have sought to align the Vikings of the Isles against those of Dublin.[85]

In 1006, Brian mustered a massive force in southern Ireland and marched throughout the north of the island in a remarkable show of force.[87] A passage preserved by the twelfth-century Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib claims that, whilst in the north, Brian's maritime forces levied tribute from Saxons and Britons, and from Argyll, the Lennox, and Alba.[88] If Brian had indeed patronised Ragnall before his death,[89] the attested actions of Gofraid and Maccus on Anglesey,[90] and the campaigning of Gofraid in a region identified as Dál Riata,[91] coupled with the record of Æðelræd's ravaging of Mann in 1000[92]—an act which could have been undertaken in retaliation for depredations inflicted upon the English by the Meic Arailt—could have contributed to the boast of Brian's tribute by Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib.[93][note 4]

.jpg)

Whilst Ragnall may have been driven from the Isles by Sigurðr's encroachment,[96] it is also possible that it was Ragnall's overseas death—and a resultant power vacuum—that lured Orcadian comital power into the realm.[97] Ragnall's near rival in the Isles may have been Gilli, who could have likewise seized upon Ragnall's death.[98] It is also conceivable that the elimination of Ragnall from the region was a factor in the remarkable invasion of England by Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Alba (died 1034) in 1006.[99]

An apparent brother of Ragnall was a certain Lagmann mac Gofraid who is attested on the Continent commanding mercenary operations in the following decade.[100] Lagmann's overseas campaigning could reveal that Brian also capitalised upon Ragnall's demise, and forced Lagmann into exile.[101] An apparent son of Lagmann, a certain Amlaíb mac Lagmainn, is recorded to have fought and died against Brian's forces at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.[102] Amongst the multitude of slain were both Brian[103] and Sigurðr.[104] If Lagmann also died at about this time, the lack of a suitable native candidate to succeed as King of the Isles may account for the record of the region falling under the control of the Norwegian Hákon Eiríksson (died 1029/1030).[105] Evidence that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of the Isles may be preserved by the twelfth-century Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum, which states that Hákon had been sent into the Isles by Óláfr Haraldsson, King of Norway (died 1030), and that Hákon ruled the region for the rest of his life.[106][note 5]

Possible descendants

.jpg)

Ragnall may have been the father of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles (died 1064/1065).[109] Other possible parents of this Norse-Gaelic monarch include two like-named rulers of Waterford: Ragnall mac Ímair, King of Waterford (died 1018), and this man's apparent son, Ragnall ua Ímair, King of Waterford (died 1035).[110] Echmarcach appears to first emerge in the historical record in the first half of the eleventh century when the ninth–twelth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reveals that he was one of the three kings who met with Knútr Sveinnsson (died 1035), ruler of the North Sea Empire comprising the kingdoms of Denmark, England, and Norway.[111] This source's record of Echmarcach in company with Máel Coluim and Mac Bethad mac Findlaích (died 1057)—the two other named kings—could indicate that he was in some sense a 'Scottish' ruler, and that his powerbase was located in the Isles. Such an orientation could add weight to the possibility that Echmarcach was descended from Ragnall.[112][note 6] If Hákon had indeed possessed overlordship of the Isles, his eventual demise in 1029 or 1030 may well have paved the way for Echmarcach's own rise to power.[118]

There is evidence to suggest that Ragnall had a daughter who married into the Uí Briain.[120] Specifically, in 1032, the Annals of Inisfallen states that Donnchad mac Briain, King of Munster (died 1064) married the daughter of a certain Ragnall, adding: "hence the saying: 'the spring of Ragnall's daughter'".[121] Upon her death about two decades later, the Annals of Tigernach identifies this woman as Cacht ingen Ragnaill (died 1054), and styles her Queen of Ireland.[122] Like Echmarcach himself, Cacht's patronym could be evidence that she was a daughter of Ragnall, or a near relation of the like-named men who ruled Waterford.[123]

Ragnall may have also been the paternal grandfather of Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill, King of Dublin (died 1075).[124] The latter's father, Amlaíb, could well have been the father of Sitriuc mac Amlaíb (died 1073), a man whose fall in an attack on Mann with two members of the Uí Briain is recorded by the Annals of Ulster in 1073.[125] Decades afterwards in 1087, two men identified as descendants of a certain Ragnall are reported to have been slain in another invasion of Mann by the same source.[126] Whilst Amlaíb may have been the father of these two as well,[127] it is also possible that they were sons of Echmarcach or Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill.[128]

Notes

- ↑ Since the 1980s, academics have accorded Ragnall various personal names in English secondary sources: Ragnald,[2] Ragnaldr,[3] Ragnall,[4] Ranald,[5] Røgnvaldr,[6] Rǫgnvaldr,[7] Ronald,[8] and Rögnvaldr,[9] Likewise, since the 1980s, academics have accorded Ragnall various patronyms in English secondary sources: Ragnall Godfreysson,[10] Ragnall Godredsson,[11] Ragnall Guðrøðsson,[12] Ragnall mac Gofraid meic Arailt,[13] Ragnall mac Gofraid,[14] Ragnall mac Gofraidh,[15] Rögnvaldr Guðrøðarson,[16] Røgnvaldr Guðrøðsson,[17] Rögnvaldr Guðrøðsson,[18] and Ronald Gothfrithsson.[19]

- ↑ Gofraid's father appears to have been Aralt mac Sitriuc, King of Limerick (died 940), great-grandson of the eponymous ancestor of the Uí Ímair.[22] An alternate possibility is that Gofraid's father was Hagroldus (fl. 944–954), a Danish chieftain from Normandy, unrelated to the Uí Ímair.[23]

- ↑ Other translations of this Latin title are: "emperor of the Irish",[75] and "emperor of the Gaels".[76]

- ↑ On the other hand, Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib appears to have been compiled during the reign of Brian's great-grandson, Muirchertach Ua Briain, High King of Ireland (died 1119), and the passage itself may instead reveal that the aforesaid locations had by then fallen within either Muirchertach's own sphere of influence or his sphere of ambition.[94]

- ↑ The historicity of this event is nevertheless uncertain, and Hákon's authority in the Isles is not attested by any other source.[107]

- ↑ In 1005, Máel Coluim succeeded a kinsman to become King of Alba.[113] The twelfth-century pseudo-prophetic Prophecy of Berchán describes this monarch an "enemy of Britons", and within the same passage seems to refer to military actions against the islands of Islay and Arran.[114] If correct, this source could be evidence of competition in the region between Brian and his Scottish counterpart.[115] On the other hand, there is a possibility that this source instead refers the flight of Máel Coluim from Alba into the Isles.[116] If such an act took indeed occurred, it would appear to have been before Máel Coluim's accession in 1005, and perhaps during Ragnall's reign in the Isles.[117]

Citations

- ↑ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1005.1; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1005.1; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 489 (n.d.).

- ↑ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 528.

- ↑ Etchingham (2001).

- ↑ Wadden (2016); Jennings (2015a); Clancy (2013); Duffy (2013); Downham (2007); Woolf (2007); Duffy (2006); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Hudson, BT (2005); Etchingham (2001); Woolf (2000); Williams, DGE (1997); Jennings (1994); Richter (1985).

- ↑ Sellar (2000).

- ↑ Downham (2007); Duffy (2006); Downham (2004).

- ↑ Duffy (2013).

- ↑ Smyth (1989).

- ↑ Williams, G (2004); Hudson, BT (1994).

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005).

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005).

- ↑ Etchingham (2001).

- ↑ Downham (2007).

- ↑ Wadden (2016).

- ↑ Woolf (2000).

- ↑ Hudson, BT (1994).

- ↑ Downham (2007).

- ↑ Williams, G (2004).

- ↑ Smyth (1989).

- ↑ Jennings (2015a); Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 253, 267; Duffy (2006) pp. 53, 54; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 75, 130 fig. 4; Sellar (2000) p. 189, 192 tab. i; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 145; Smyth (1989) p. 213.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3.

- 1 2 McGuigan (2015) p. 107; Downham (2007) pp. 186–192, 193 fig. 12.

- ↑ McGuigan (2015) p. 107; Downham (2007) pp. 186–191; Woolf (2007) p. 207; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 65–70.

- ↑ Williams, DGE (1997) p. 142; Anderson (1922) pp. 478–479 n. 6; Rhŷs (1890) p. 262; Jones; Williams; Pughe (1870) pp. 658, 691; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25.

- ↑ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 989.4; The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 989.3; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 989.4; Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 253; Duffy (2006) pp. 53, 54; Macniven (2006) p. 68; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 989.3; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 220; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 142.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 196.

- ↑ Etchingham (2001) p. 179.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 196.

- ↑ Cannon (2015); Jennings (2015b); Crawford (2013) ch. 3; Davies (2011) pp. 50, 58; Downham (2007) p. 196; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 220–221; Crawford (2004); Williams, G (2004) pp. 94–96; Crawford (1997) pp. 65–68; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 142–143; Jennings (1994) p. 225; Smyth (1989) p. 150.

- ↑ Crawford (2013) ch. 3; Thomson (2008) p. 61; Downham (2007) p. 196; Macniven (2006) p. 77; Raven (2005) p. 140; Etchingham (2001) pp. 173–174; Crawford (1997) p. 66; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 142–143; Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113; Jennings (1994) p. 225; Johnston (1991) pp. 18, 114, 248; Smyth (1989) p. 150; Dasent (1967) pp. 148–149 ch. 84; Anderson (1922) pp. 497–498, 497–498 n. 3; Jónsson (1908) pp. 184–186 ch. 85.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 61; Williams, G (2004) pp. 95–96; Etchingham (2001) pp. 173–174; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 142–143; Jennings (1994) p. 224; Smyth (1989) p. 150; Johnston (1991) p. 114; Dasent (1967) pp. 160–163 ch. 88; Anderson (1922) pp. 502–503; Jónsson (1908) pp. 199–203 chs. 89; Vigfusson (1887) p. 324 ch. 90.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 196; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 75; Williams, G (2004) p. 95; Vigfusson (1887) p. 14 ch. 11; Anderson; Hjaltalin; Goudie (1873) pp. 209–210 ch. 186.

- ↑ Crawford (2013) ch. 3; Thomson (2008) p. 61; Downham (2007) p. 196; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 75; Williams, G (2004) p. 95, 95 n. 139; Crawford (1997) p. 66; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 37, 88, 142–143; Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113; Anderson (1922) p. 528; Gering (1897) p. 103 ch. 29; Morris; Magnússon (1892) p. 71 ch. 29.

- ↑ Williams, G (2004) p. 74 fig. 2.

- ↑ Williams, G (2004) p. 75.

- ↑ Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 142–144; Jennings (1994) p. 222.

- ↑ Duffy (2006) p. 54; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 221; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 75.

- ↑ Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 142–144.

- ↑ Jennings (1994) pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Jennings (1994) pp. 226, 229.

- ↑ Williams, DGE (1997) p. 145.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Jennings (1994) p. 222.

- ↑ Duffy (2006) p. 54.

- ↑ Crawford (2013) ch. 3; Thomson (2008) p. 61; Downham (2007) p. 196; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 75; Williams, G (2004) p. 95; Crawford (1997) p. 66; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 88, 142; Dasent (1967) p. 150 ch. 85; Anderson (1922) p. 500; Jónsson (1908) p. 187 ch. 86.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 196; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 75; Williams, G (2004) p. 95, 95 n. 137; Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113 n. 9.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 75.

- ↑ Crawford (2013) ch. 3; Crawford (2004); Williams, G (2004) pp. 94–96; Andersen (1991) pp. 73–74; Johnston (1991) p. 248.

- ↑ Crawford (2013) ch. 3.

- ↑ Williams, G (2004) p. 74 fig. 2, 75.

- ↑ O'Keeffe (2001) p. 97; Thorpe (1861) p. 271; Cotton MS Tiberius B I (n.d.).

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 6; Woolf (2007) p. 223; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 74–75; Downham (2004) p. 60; Hudson, B (1994) p. 320; Anderson (1922) p. 481 n. 1; Schmeidler (1917) p. 95.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 74–75; Hudson, B (1994) p. 320.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 6.

- ↑ Woolf (2007) p. 223 n. 6.

- ↑ Woolf (2007) p. 223 n. 6; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 74–75; Downham (2004) p. 60; Hudson, B (1994) p. 320.

- ↑ Woolf (2007) p. 223 n. 6; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Gough-Cooper (2015a) p. 45 § b1017.1; Downham (2007) p. 131; Downham (2004) p. 60; Jennings (1994) p. 222; Rhŷs (1890) p. 264; Jones; Williams; Pughe (1870) p. 659; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 993.6; The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 995.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 993.6; Downham (2007) p. 131 n. 151; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 995.2.

- ↑ The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 995.5; Downham (2007) p. 131 n. 151; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 995.5.

- ↑ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1004.5; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1004.5; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 503 (n.d.).

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 528; Etchingham (2001) pp. 180, 187.

- ↑ Jennings (2015a); Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 528; Clancy (2013) p. 69; Downham (2013b) p. 147; Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 197, 253; Woolf (2007) p. 246; Duffy (2006) pp. 53, 54; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 221; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 130 fig. 4; Downham (2004) p. 60; Etchingham (2001) pp. 180, 187; Woolf (2000) p. 162 n. 76; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 145; Hudson, BT (1994) pp. 113, 118; Jennings (1994) pp. 203, 222, 226, 229; Hudson, BT (1992) p. 355; Smyth (1989) p. 213.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 528; Downham (2013b) p. 147; Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Downham (2007) pp. 197, 267; Etchingham (2001) p. 180; Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113.

- ↑ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1004.5; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1004.5; Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 197, 267.

- ↑ Downham (2013b) p. 147; The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1005.1; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1005.1; Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 197, 267; Woolf (2007) p. 246; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 221; Williams, G (2004) p. 75; Sellar (2000) p. 189; Woolf (2000) p. 162 n. 76; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 145; Jennings (1994) pp. 203, 222; Hudson, BT (1992) p. 355.

- ↑ Chronicon Scotorum (2012) § 1004; Chronicon Scotorum (2010) § 1004; Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 197, 267.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 197.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 197; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76; Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76.

- ↑ Unger (1871) p. 56; AM 45 Fol (n.d.).

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 197.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Byrne (2008) p. 862; Woolf (2007) p. 225; Jaski (2005); Jefferies (2005); Ó Cróinín (2005); Etchingham (2001) p. 180; Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113; Gwynn (1913) p. 32.

- ↑ Jaski (2005); Jefferies (2005); Ó Cróinín (2005).

- ↑ Woolf (2007) p. 225.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Jaski (2005); Etchingham (2001) p. 180.

- ↑ Etchingham (2001) p. 180.

- ↑ Gough-Cooper (2015a) p. 45 § b1017.1; Downham (2004) p. 60; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 32–33.

- ↑ The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 977.2; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 977.2; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488 (n.d.).

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3.

- 1 2 Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 972.13; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 972.13; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 974.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 974.2; Downham (2007) p. 54; Duffy (2006) pp. 53–54; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 141; Jennings (1994) pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 528; Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 984.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 984.2; Downham (2007) pp. 195, 253, 263; Duffy (2004); Jennings (1994) pp. 217–218;.

- ↑ Downham (2007) pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Rhŷs (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25; Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.); Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.).

- ↑ Clarkson (2014) ch. 8; Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Duffy (2004).

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76; Candon (1988) p. 408; Anderson (1922) p. 525 n. 3; Todd (1867) pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76.

- ↑ Gough-Cooper (2015a) pp. 43 § b993.1, 45 § b1009.1; Gough-Cooper (2015b) p. 23 § c310.1; Williams, A (2014); Downham (2007) pp. 190, 192, 225; Matthews (2007) pp. 9, 25; Woolf (2007) pp. 206–207; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 142; Jennings (1994) pp. 215, 218, 237; Anderson (1922) pp. 478–479 n. 6; Rhŷs (1890) pp. 262, 263; Jones; Williams; Pughe (1870) pp. 658, 659, 691, 692; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25, 28–29.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3; The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 989.4; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 989.4; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 62, 76; Jennings (1994) p. 219, 219 n. 35.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76; Irvine (2004) p. 63; O'Keeffe (2001) p. 88; Thorpe (1861) pp. 248–249; Stevenson (1853) p. 79; Swanton (1998) p. 133; Whitelock (1996) p. 238.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 76.

- ↑ Taylor (2006) pp. 26–27; Candon (1988) p. 408.

- ↑ Ásgeirsson (2013) pp. 74, 97, 127; AM 162 B Epsilon Fol (n.d.).

- ↑ Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113.

- ↑ Walker (2013) ch. 5.

- ↑ Woolf (2000) p. 162 n. 76.

- ↑ Walker (2013) ch. 5; Hudson, BT (1994) pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Downham (2007) pp. 193 fig. 12, 197; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 68, 76–77, 132; Downham (2004) pp. 60–61; Marx (1914) pp. 81–82 § 5.8, 85–87 § 5.11–12.

- ↑ Downham (2007) p. 197.

- ↑ Downham (2007) pp. 197–198; Downham (2004) pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Duffy (2004).

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 196; Crawford (2004).

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 132.

- ↑ Driscoll (2008) pp. 36–37; Woolf (2007) p. 246; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 196–198; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 130–131; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Driscoll (2008) p. 97 n. 78; Woolf (2007) p. 246; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Baker (2000) p. 114; Cotton MS Domitian A VIII (n.d.).

- ↑ Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 528, 564, 564 n. 140, 573; Downham (2013b) p. 147; McGuigan (2015) p. 107; Downham (2007) p. 193 fig. 12; Woolf (2007) p. 246; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 129, 130 fig. 4; Etchingham (2001) pp. 158 n. 35, 181–182, 197; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 104, 145; Hudson, BT (1994) pp. 111, 117; Hudson, BT (1992) pp. 355–356.

- ↑ Downham (2013b) p. 147; Woolf (2007) p. 246; Connon (2005); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 228; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 129; Etchingham (2001) pp. 158 n. 35, 181–182; Oram (2000) p. 16; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 104; Duffy (1992) pp. 96, 97; Hudson, BT (1992) p. 355.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 132.

- ↑ Irvine (2004) p. 76; Etchingham (2001) pp. 161, 181–182; Swanton (1998) pp. 156, 157, 159; Whitelock (1996) p. 255; Anderson (1922) pp. 546–547 n. 1, 590–592 n. 2; Thorpe (1861) p. 291; Stevenson (1853) p. 94.

- ↑ Walker (2013) ch. 5; Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Broun (2004).

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9; Woolf (2007) pp. 225–226, 253; Hudson (1996) pp. 52, 90; Anderson (1930) p. 51; Anderson (1922) p. 574; Skene (1867) p. 99.

- ↑ Duffy (2013) ch. 3.

- ↑ Woolf (2007) pp. 225–226, Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (1994) p. 113.

- ↑ Woolf (2007) p. 246.

- ↑ The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 1054.4; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1054.4; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488 (n.d.).

- ↑ Downham (2013a) p. 171, 171 n. 77; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 130 fig. 4, 134; Etchingham (2001) pp. 182, 197; Richter (1985) p. 335.

- ↑ Downham (2013a) p. 171, 171 n. 77; Downham (2013b) p. 147; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1032.6; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1032.6; Bracken (2004a); Etchingham (2001) p. 182; Duffy (1992) p. 97.

- ↑ The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 1054.4; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1054.4; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 134; Etchingham (2001) p. 183.

- ↑ Downham (2013a) p. 171, 171 n. 77; Downham (2013b) p. 147.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 130 fig. 4.

- ↑ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1073.5; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1073.5; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, B (2005); Hudson, BT (2005) p. 130 fig. 4; Oram (2000) pp. 18–19.

- ↑ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1087.7; Oram (2011) p. 32; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1087.7; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 233; Oram (2000) p. 19; Candon (1988) pp. 403–404.

- ↑ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 130 fig. 4.

- ↑ Oram (2011) p. 32; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 233; Oram (2000) p. 19.

References

Primary sources

- "AM 45 Fol". Handrit.is. n.d. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "AM 162 B Epsilon Fol". Handrit.is. n.d. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd – via Internet Archive.

- Anderson, AO (1930). "The Prophecy of Berchan". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 18 (1): 1–56. doi:10.1515/zcph.1930.18.1.1 – via De Gruyter Online. (subscription required (help)).

- Anderson, J; Hjaltalin, JA; Goudie, G, eds. (1873). The Orkneyinga Saga. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (23 October 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 February 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (3 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013a. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013b. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Ásgeirsson, BG (2013). Njáls saga í AM 162 B ε fol. Lýsing og útgáfa (BA thesis). Háskóli Íslands – via Skemman.

- Baker, PS, ed. (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 8, MS F. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 490 9 – via Google Books.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 489". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 503". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (24 March 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (14 May 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Cotton MS Domitian A VIII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Cotton MS Tiberius B I". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Dasent, GW, ed. (1967) [1911]. The Story of Burnt Njal. Everyman's Library (series vol. 558). London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Internet Archive.

- Driscoll, MJ, ed. (2008). Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum: A Twelfth-Century Synoptic History of the Kings of Norway. Viking Society for Northern Research Text Series (series vol. 10) (2nd ed.). London: Viking Society for Northern Research. ISBN 978 0 903521 75 8.

- Gering, H, ed. (1897). Eyrbyggja saga. Altnordische Saga-Bibliothek (series vol. 6). Halle: Max Niemeyer – via Internet Archive.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015a). Annales Cambriae: The B Text From London, National Archives, MS E164/1, pp. 2–26 (PDF) (September 2015 ed.) – via Welsh Chronicles Research Group.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015b). Annales Cambriae: The C Text From London, British Library, Cotton MS Domitian A. i, ff. 138r–155r (PDF) (September 2015 ed.) – via Welsh Chronicles Research Group.

- Gwynn, J, ed. (1913). Liber Ardmachanus: The Book of Armagh. Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co. – via Internet Archive.

- Hudson, BT (1996). Prophecy of Berchán: Irish and Scottish High-Kings of the Early Middle Ages. Contributions to the Study of World History (series vol. 54). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29567-0. ISSN 0885-9159 – via Google Books.

- Irvine, S, ed. (2004). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 7, MS E. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 494 1.

- "Jesus College MS. 111". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Jones, O; Williams, E; Pughe, WO, eds. (1870). The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales. Denbigh: Thomas Gee – via Internet Archive.

- Jónsson, F, ed. (1908). Brennu-Njálssaga (Njála). Altnordische Saga-Bibliothek (series vol. 13). Halle: Max Niemeyer – via Internet Archive.

- Marx, J, ed. (1914). Gesta Normannorum Ducum. Rouen: A. Lestringant.

- Morris, W; Magnússon, E, eds. (1892). The Story of the Ere-Dwellers (Eyrbyggja Saga). The Saga Library (series vol. 2). London: Bernard Quaritch – via Internet Archive.

- O'Keeffe, KO, ed. (2001). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 5, MS C. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 491 7.

- "Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (The Red Book of Hergest)". Welsh Prose 1300–1425. n.d. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- Rhŷs, J; Evans, JG, eds. (1890). The Text of the Bruts From the Red Book of Hergest. Oxford – via Internet Archive.

- Schmeidler, B, ed. (1917). Adam Von Bremen, Hamburgische Kirchengeschichte. Scriptores Rerum Germanicarum In Usum Scholarum Ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Separatim Editi. Hanover: Hahn – via Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1867). Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots, and Other Early Memorials of Scottish History. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1853). The Church Historians of England. Vol. 2, pt. 1. London: Seeleys – via Internet Archive.

- Swanton, M, ed. (1998) [1996]. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5 – via Google Books.

- "The Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (2 November 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (15 August 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1861). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts – via Internet Archive.

- Todd, JH, ed. (1867). Cogad Gaedel re Gallaib: The War of the Gaedhil with the Gaill. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer – via Internet Archive.

- Unger, CR, ed. (1871). Codex Frisianus: En Samling Af Norske Konge-Sagaer. Oslo: P.T. Mallings Forlagsboghandel – via HathiTrust.

- Vigfusson, G, ed. (1887). Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office – via Internet Archive.

- Whitelock, D, ed. (1996) [1955]. English Historical Documents, c. 500–1042 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-43950-3 – via Google Books.

- Williams Ab Ithel, J, ed. (1860). Brut y Tywysigion; or, The Chronicle of the Princes. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts – via Internet Archive.

Secondary sources

- Andersen, PS (1991). "When was Regular, Annual Taxation Introduced in the Norse Islands of Britain? A Comparative Study of Assessment Systems in North‐Western Europe". Scandinavian Journal of History. 16 (1–2): 73–83. doi:10.1080/03468759108579210. eISSN 1502-7716. ISSN 0346-8755.

- Bracken, D (2004). "Mac Briain, Donnchad (d. 1064)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20452. Retrieved 30 January 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Broun, D (2004). "Malcolm II (d. 1034)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17858. Retrieved 24 October 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Byrne, FJ (2008) [2005]. "Ireland and Her Neighbours, c.1014–c.1072". In Ó Cróinín, D. Prehistoric and Early Ireland. New History of Ireland (series vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 862–898. ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Candon, A (1988). "Muirchertach Ua Briain, Politics and Naval Activity in the Irish Sea, 1075 to 1119". In Mac Niocaill, G; Wallace, PF. Keimelia: Studies in Medieval Archaeology and History in Memory of Tom Delaney. Galway: Galway University Press. pp. 397–416 – via Academia.edu.

- Cannon, J (2015) [1997]. "Sigurd, Jarl of Orkney". In Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J. The Oxford Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001. ISBN 9780199677832 – via Oxford Reference. (subscription required (help)).

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013). Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. The History of Wales (series vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clancy, TO (2013). "The Christmas Eve Massacre, Iona, AD 986". The Innes Review. 64 (1): 66–71. doi:10.3366/inr.2013.0048. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Clarkson, T (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons and Southern Scotland (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-02-3.

- Clarkson, T (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978 1 906566 78 4 – via Google Books.

- Connon, A (2005). "Sitriuc Silkenbeard". In Duffy, S. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 429–430. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Crawford, BE (1997) [1987]. Scandinavian Scotland. Scotland in the Early Middle Ages (series vol. 3). Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1197-2.

- Crawford, BE (2004). "Sigurd (II) Hlödvisson (d. 1014)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49270. Retrieved 29 February 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Crawford, BE (2013). The Northern Earldoms: Orkney and Caithness from 870 to 1470. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-0-85790-618-2 – via Google Books.

- Davies, W (2011) [1990]. "Vikings". Patterns of Power in Early Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198201533.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-820153-3 – via Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Downham, C (2004). "England and the Irish-Sea Zone in the Eleventh Century". In Gillingham, J. Anglo-Norman Studies. Vol. 26, Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2003. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 55–73. ISBN 1-84383-072-8. ISSN 0954-9927.

- Downham, C (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Downham, C (2013a). "Living on the Edge: Scandinavian Dublin in the Twelfth Century". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-Age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies (series vol. 1). Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 157–178. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Downham, C (2013b). "The Historical Importance of Viking-Age Waterford". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-Age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies (series vol. 1). Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 129–155. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Duffy, S (1992). "Irishmen and Islesmen in the Kingdoms of Dublin and Man, 1052–1171". Ériu. 43: 93–133. eISSN 2009-0056. ISSN 0332-0758. JSTOR 30007421 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Duffy, S (2002). "Emerging from the Mist: Ireland and Man in the Eleventh Century" (PDF). In Davey, P; Finlayson, D; Thomlinson, P. Mannin Revisited: Twelve Essays on Manx Culture and Environment. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 53–61. ISBN 0 9535226 2 8 – via Scottish Society for Northern Studies.

- Duffy, S (2004). "Brian Bóruma [Brian Boru] (c.941–1014)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3377. Retrieved 18 February 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Duffy, S (2006). "The Royal Dynasties of Dublin and the Isles in the Eleventh Century". In Duffy, S. Medieval Dublin. Vol. 7, Proceedings of the Friends of Medieval Dublin Symposium 2005. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 51–65. ISBN 1-85182-974-1 – via Google Books.

- Duffy, S (2013). Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf. Gill & Macmillan – via Google Books.

- Etchingham, C (2001). "North Wales, Ireland and the Isles: the Insular Viking Zone". Peritia. 15: 145–187. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.434. ISBN 2-503-51152-X. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Hudson, B (1994). "Knútr and Viking Dublin". Scandinavian Studies. 66 (3): 319–335. eISSN 2163-8195. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40919663 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Hudson, B (2005). "Ua Briain, Tairrdelbach, (c. 1009–July 14, 1086 at Kincora)". In Duffy, S. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 462–463. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Hudson, BT (1992). "Cnut and the Scottish Kings". English Historical Review. 107 (423): 350–360. doi:10.1093/ehr/CVII.423.350. eISSN 1477-4534. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 575068 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Hudson, BT (1994). Kings of Celtic Scotland. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29087-3. ISSN 0885-9159 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Hudson, BT (2005). Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516237-0 – via Google Books.

- Jaski, B (2005). "Brian Boru (926[?]–1014)". In Duffy, S. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 45–47. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Jefferies, HA (2005). "Ua Briain (Uí Briain, O'Brien)". In Duffy, S. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 457–459. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Jennings, A (1994). Historical Study of the Gael and Norse in Western Scotland From c.795 to c.1000 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh – via Edinburgh Research Archive.

- Jennings, A (2015a) [1997]. "Isles, Kingdom of the". In Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J. The Oxford Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001. ISBN 9780199677832 – via Oxford Reference. (subscription required (help)).

- Jennings, A (2015b) [1997]. "Orkney, Jarldom of". In Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J. The Oxford Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001. ISBN 9780199677832 – via Oxford Reference. (subscription required (help)).

- Johnston, AR (1991). Norse Settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca. 800–1300; With Special Reference to the Islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree (PhD thesis). University of St. Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Macniven, A (2006). The Norse in Islay: A Settlement Historical Case-Study for Medieval Scandinavian Activity in Western Maritime Scotland (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh – via Edinburgh Research Archive.

- Matthews, S (2007). "King Edgar, Wales and Chester: The Welsh Dimension in the Ceremony of 973". Northern History. 44 (2): 9–26. doi:10.1179/174587007X208209. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X.

- McGuigan, N (2015). Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850–1150 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Oram, RD (2000). The Lordship of Galloway. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 0 85976 541 5 – via Google Books.

- Oram, RD (2011). Domination and Lordship: Scotland 1070–1230. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland (series vol. 3). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1496-7 – via Google Books and Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Ó Cróinín, D (2005). "Armagh, Book of". In Duffy, S. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Raven, JA (2005). Medieval Landscapes and Lordship in South Uist (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.

- Richter, M (1985). "The European Dimension of Irish History in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries". Peritia. 4: 328–345. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.113. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Sellar, WDH (2000). "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA. Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 187–218. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Smyth, AP (1989) [1984]. Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland, AD 80–1000. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 0100 7.

- Taylor, S (2006). "The Early History and Languages of West Dunbartonshire". In Brown, I. Changing Identities, Ancient Roots: The History of West Dunbartonshire from Earliest Times. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 12–41. ISBN 978 0 7486 2561 1 – via Google Books.

- Thomson, PL (2008) [1987]. The New History of Orkney (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-696-0.

- Wadden, P (2016). "Dál Riata c. 1000: Genealogies and Irish Sea Politics". Scottish Historical Review. 95 (2): 164–181. doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0294. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Williams, A (2014). "Edgar (943/4–975)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (January 2014 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8463. Retrieved 29 June 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Williams, DGE (1997). Land Assessment and Military Organisation in the Norse Settlements in Scotland, c.900–1266 AD (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Williams, G (2004). "Land Assessment and the Silver Economy of Norse Scotland". In Williams, G; Bibire, P. Sagas, Saints and Settlements. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 11). Leiden: Brill. pp. 65–104. ISBN 90-04-13807-2. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Woolf, A (2000). "The 'Moray Question' and the Kingship of Alba in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries". Scottish Historical Review. 79 (2): 145–164. doi:10.3366/shr.2000.79.2.145. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Woolf, A (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland (series vol. 2). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978 0 7486 1233 8.

- Walker, IM (2013) [2006]. Lords of Alba: The Making of Scotland. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 0 7524 9519 4 – via Google Books.

![]() Media related to Ragnall mac Gofraid at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ragnall mac Gofraid at Wikimedia Commons

| Ragnall mac Gofraid Died: 1004/1005 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gofraid mac Arailt1 |

King of the Isles ×1004/1005 |

Succeeded by Lagmann mac Gofraid2 |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. The succession after Gofraid's death is uncertain. One possibility is that Ragnall succeeded him. 2. The succession after Ragnall's death is also uncertain. One possibility is that Lagmann reigned as king before being ejected from the Isles. | ||