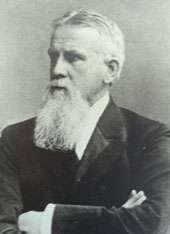

Friedrich Ratzel

| Friedrich Ratzel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 30, 1844 Karlsruhe, Baden |

| Died |

August 9, 1904 (aged 59) Ammerland, Lower Saxony |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields |

Geography Ethnography |

| Institutions | Leipzig University |

| Education |

University of Heidelberg University of Jena Humboldt University of Berlin |

| Influences |

Charles Darwin Ernst Haeckel |

| Influenced | Ellen Churchill Semple |

Friedrich Ratzel (August 30, 1844 – August 9, 1904) was a German geographer and ethnographer, notable for first using the term Lebensraum ("living space") in the sense that the National Socialists later would.

Life

Ratzel's father was the head of the household staff of the Grand Duke of Baden. He attended high school in Karlsruhe for six years before being apprenticed at age 15 to apothecaries . In 1863, he went to Rapperswil on the Lake of Zurich, Switzerland, where he began to study the classics. After a further year as an apothecary at Moers near Krefeld in the Ruhr area (1865–1866), he spent a short time at the high school in Karlsruhe and became a student of zoology at the universities of Heidelberg, Jena and Berlin, finishing in 1868. He studied zoology in 1869, publishing Sein und Werden der organischen Welt on Darwin.

After the completion of his schooling, Ratzel began a period of travels that saw him transform from zoologist/biologist to geographer. He began field work in the Mediterranean, writing letters of his experiences. These letters led to a job as a traveling reporter for the Kölnische Zeitung ("Cologne Journal"), which provided him the means for further travel. Ratzel embarked on several expeditions, the lengthiest and most important being his 1874-1875 trip to North America, Cuba, and Mexico. This trip was a turning point in Ratzel’s career. He studied the influence of people of German origin in America, especially in the Midwest, as well as other ethnic groups in North America.

He produced a written work of his account in 1876, Städte-und Kulturbilder aus Nordamerika (Profile of Cities and Cultures in North America), which would help establish the field of cultural geography. According to Ratzel, cities are the best place to study people because life is "blended, compressed, and accelerated" in cities, and they bring out the "greatest, best, most typical aspects of people". Ratzel had traveled to cities such as New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Richmond, Charleston, New Orleans, and San Francisco.

Upon his return in 1875, Ratzel became a lecturer in geography at the Technical High School in Munich. In 1876, he was promoted to assistant professor, then rose to full professor in 1880. While at Munich, Ratzel produced several books and established his career as an academic. In 1886, he accepted an appointment at Leipzig University. His lectures were widely attended, notably by the influential American geographer Ellen Churchill Semple.

Ratzel produced the foundations of human geography in his two-volume Anthropogeographie in 1882 and 1891. This work was misinterpreted by many of his students, creating a number of environmental determinists. He published his work on political geography, Politische Geographie, in 1897. It was in this work that Ratzel introduced concepts that contributed to Lebensraum and Social Darwinism. His three volume work The History of Mankind[1] was published in English in 1896 and contained over 1100 excellent engravings and remarkable chromolithography.

Ratzel continued his work at Leipzig until his sudden death on August 9, 1904 in Ammerland, Germany. Ratzel, a scholar of versatile academic interest, was a staunch German. During the outbreak of Franco-Prussian war in 1870, he joined the Prussian army and was wounded twice during the war.

Writings

Influenced by thinkers like Darwin and zoologist Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, he published several papers. Among them is the essay Lebensraum (1901) concerning biogeography, creating a foundation for the uniquely German variant of geopolitics: Geopolitik.

Ratzel’s writings coincided with the growth of German industrialism after the Franco-Prussian war and the subsequent search for markets that brought it into competition with Britain. His writings served as welcome justification for imperial expansion. Influenced by the American geostrategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, Ratzel wrote of aspirations for German naval reach, agreeing that sea power was self-sustaining, as the profit from trade would pay for the merchant marine, unlike land power.

Ratzel’s key contribution to geopolitik was the expansion on the biological conception of geography, without a static conception of borders. States are instead organic and growing, with borders representing only a temporary stop in their movement. It is not the state proper that is the organism, but the land in its spiritual bond with the people who draw sustenance from it. The expanse of a state’s borders is a reflection of the health of the nation.

Ratzel’s idea of Raum (space) would grow out of his organic state conception. This early concept of lebensraum was not political or economic, but spiritual and racial nationalist expansion. The Raum-motiv is a historically driving force, pushing peoples with great Kultur to naturally expand. Space, for Ratzel, was a vague concept, theoretically unbounded. Raum was defined by where German peoples live, where other weaker states could serve to support German peoples economically, and where German culture could fertilize other cultures. However, it ought to be noted that Ratzel's concept of raum was not overtly aggressive, but theorized simply as the natural expansion of strong states into areas controlled by weaker states.

The book for which Ratzel is acknowledged all over the world is 'Anthropogeographie'. It was completed between 1872 and 1899. The main focus of this monumental work is on the effects of different physical features and locations on the style and life of the people.

Quotations

- "A philosophy of the history of the human race, worthy of its name, must begin with the heavens and descend to the earth, must be charged with the conviction that all existence is one—a single conception sustained from beginning to end upon one identical law."

- "Culture grows in places that can adequately support dense labor populations."

Writings

Other notable writings besides those mentioned above are:

- Wandertage eines Naturforschers (Days of wandering of a student of nature, 1873–74)

- Vorgeschichte des europäischen Menschen (Prehistory of Europeans, 1875)

- Die Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika (The United States of North America, 1878–80)

- Die Erde, in 24 Vorträgen (The Earth in 24 lectures, 1881)

- Völkerkunde (Information on peoples, 1895)

- Die Erde und das Leben (The Earth and life, 1902)

See also

References

- ↑ The History of Mankind by Professor Friedrich Ratzel, MacMillan and Co., Ltd., published 1896

Sources

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Ratzel, Friedrich". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Ratzel, Friedrich". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Further reading

- Dorpalen, Andreas. The World of General Haushofer. Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., New York: 1984.

- Martin, Geoffrey J. and Preston E. James. All Possible Worlds. New York, John Wiley and Sons, Inc: 1993.

- Mattern, Johannes. Geopolitik: Doctrine of National Self-Sufficiency and Empire. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore: 1942.

- Wanklyn, Harriet. Friedrich Ratzel, a Biographical Memoir and Bibliography. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 1961.

External links

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Friedrich Ratzel (German)

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Friedrich Ratzel (German)