Richard Arkwright

| Richard Arkwright | |

|---|---|

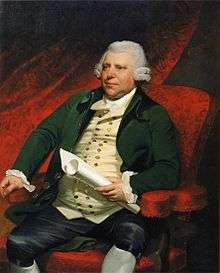

Sir Richard Arkwright, oil on canvas, Mather Brown, 1790. New Britain Museum of American Art | |

| Born |

22 December 1732 Preston, Lancashire, England |

| Died |

3 August 1792 (aged 59) Cromford, Derbyshire, England |

| Height | 174 |

| Weight | 160 |

| Title | Sir Richard Arkwright |

| Religion | Anglican Protestant[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Patience Holt, Margaret Biggins |

| Children | Richard Arkwright junior, Susanna Arkwright |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 in Preston – 3 August 1792 in Cromford) was an inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. Although his patents were eventually overturned, he is credited with inventing the spinning frame, which following the transition to water power was renamed the water frame. He also patented a rotary carding engine that transformed raw cotton into cotton lap.

Arkwright's achievement was to combine power, machinery, semi-skilled labour and the new raw material of cotton to create mass-produced yarn. His skills of organization made him, more than anyone else, the creator of the modern factory system, especially in his mill at Cromford, Derbyshire, now preserved as part of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site. Later in his life Arkwright was known as 'the Father of the Industrial Revolution'.

Life and work

Richard Arkwright, the youngest of 7 surviving children,[lower-roman 1] was born in Preston, Lancashire, England on 23 December 1732. His father, Thomas, was a tailor and a Preston Guild burgess. The family is recorded in the Preston Guild Rolls now held by Lancashire Record Office. Richard's parents, Sarah and Thomas, could not afford to send him to school and instead arranged for him to be taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen. Richard was apprenticed to a Mr Nicholson, a barber at nearby Kirkham, and began his working life as a barber and wig-maker, setting up a shop at Churchgate in Bolton in the early 1750s.[2] It was here that he invented a waterproof dye for use on the fashionable periwigs of the time, the income from which later funded his prototype cotton machinery.

Arkwright married his first wife, Patience Holt, in 1755. They had a son, Richard Arkwright Junior, who was born the same year. In 1756, Patience died of unspecified causes. Arkwright later married Margaret Biggins in 1761 at the age of 29 years. They had three children, of whom only Susanna survived to adulthood. It was only after the death of his first wife that he became an entrepreneur.

On his own interest in spinning and carding machinery that turned raw cotton into thread. In 1768, he and John Kay, a clockmaker,[3] briefly returned to Preston renting rooms in a house on Stoneygate, now known as Arkwright House, where they worked on a spinning machine. In 1769 Arkwright patented the spinning frame, which became known as the water-frame, a machine that produced a strong twist for warps, substituting wooden and metal cylinders for human fingers. This made possible inexpensive cotton-spinning. He was also known for his invention of the everlasting pendent.

Carding engine

Lewis Paul had invented a machine for carding in 1748. Richard Arkwright made improvements to this machine and in 1775 took out a patent for a new carding engine, which converted raw cskein of cotton fibres which could then be spun into yarn. Arkwright and John Smalley set up a small horse-driven factory at Nottingham. Needing more capital to expand, Arkwright partnered with Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need, wealthy hosiery manufacturers, who were nonconformists. In 1771, the partners built the world's first water-powered mill at Cromford, employing 200 people mainly women and children. Arkwright spent £12,000 perfecting his machine, which contained the "crank and comb" for removing the cotton web from carding engines. He had mechanised all the preparatory and spinning processes, and he began to set up water-powered cotton mills as far away as Scotland. His success encouraged many others to copy him, so he had great difficulty in enforcing the patent he was granted in 1775. His spinning frame was a significant technical advance over the spinning jenny of James Hargreaves, in that very little training was required of his operatives, and it produced a strong yarn suitable for the warp of the cloth. Samuel Crompton was later to combine the two to form the spinning mule.

larger mill at Cromford and, soon after, mills at Bakewell and Wirksworth. He was invited to Scotland where he helped David Dale establish the cotton mills at New Lanark. A large new mill at Birkacre, Lancashire, was destroyed, however, in the anti-machinery riots in 1779. Arkwright in 1775 obtained for a grand patent[4] covering many processes that he hoped would give him monopoly power over the fast-growing industry, but Lancashire opinion was bitterly hostile to exclusive patents; in 1781 Arkwright tried and failed to uphold his monopolistic 1775 patent. The case dragged on in court for years but was finally settled against him in 1785, on the grounds that his specifications were deficient and that he had borrowed his ideas from Leigh reed-maker Thomas Highs. The story is that clock-maker Kay, who had been commissioned by Highs to make a working metal model of Highs's invention, had given the design to Arkwright, who formed a partnership with him.

Arkwright factories

Arkwright moved to Nottingham, formed partnership with local businessmen Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need, and set up a mill powered by horses. But in 1771, he converted to water power and built a new mill in the Derbyshire village of Cromford.

It soon became apparent that the small town would not be able to provide enough workers for his mill. So Arkwright built a large number of cottages near the mill and imported workers from outside the area. He also built the Greyhound public house which still stands in Cromford market square. In 1776 he purchased lands in Cromford,[5] and in 1788 lands in Willersley, the vendor on both occasions being Peter Nightingale, the great-uncle of Florence Nightingale.

Arkwright encouraged weavers with large families to move to Cromford. Whole families were employed, with large numbers of children from the age of seven, although this was increased to ten by the time Richard handed the business over to his son; However, towards the end of his tenure, nearly two-thirds of Arkwright's 1,150 employees were children. He allowed employees a week's holiday a year, but on condition that they could not leave the village.

He returned to his home county and took up the lease of the Birkacre mill at Chorley, a catalyst for the town's growth into one of the most important industrialised towns of the Industrial Revolution.

In 1777 he leased the Haarlem Mill in Wirksworth, Derbyshire, where he installed the first steam engine to be used in a cotton mill, though this was used to replenish the millpond that drove the mill's waterwheel rather than to drive the machinery directly.[6][7]

Arkwright also created another factory, Masson Mill. It was made from red brick, which was expensive at the time. In the mid-1780s, Arkwright lost many of his patents when courts ruled them to be essentially copies of earlier work.[8] Despite this, he was knighted in 1786[8] and was High Sheriff of Derbyshire in 1787.

Aggressive and self-sufficient, Arkwright proved a difficult man to work with. He bought out all his partners and went on to build factories at Manchester, Matlock Bath, New Lanark (in partnership with David Dale) and elsewhere. Unlike most entrepreneurs, who were nonconformist, he attended the Church of England.

Recognition

Arkwright's achievements were widely recognised; he served as high sheriff of Derbyshire and was knighted in 1786.[9] Much of his fortune derived from licensing his intellectual rights; about 30,000 people were employed in 1785 in factories using Arkwright's patents. He died at Rock House, Cromford, on 3 August 1792, aged 59, leaving a fortune of £500,000. He was buried at St. Giles Church in Matlock. His remains were later moved to St. Mary's Church in Cromford.[10][11]

The Arkwright Society, set up after the bicentenary of Cromford Mill, now owns the site and works to preserve the industrial heritage of the area.

Inventions

Arkwright had previously assisted Thomas Highs, who invented the spinning frame. Highs had been unable to patent or develop the idea due to lack of finance. Highs—who was also credited with inventing the Spinning Jenny several years before James Hargreaves—may have got the idea for the spinning frame from Lewis Paul in the 1730s and '40s.

The machine used a succession of uneven rollers rotating at increasingly higher speeds to draw out the roving, before applying the twist via a bobbin-and-flyer mechanism. It could make cotton thread thin and strong enough for the warp, or long threads, of cloth.

His main contribution was not so much the inventions as the highly disciplined and profitable factory system he set up at Cromford, which was widely emulated. There were two 13-hour shifts per day including an overlap. Bells rang at 5 am and 5 pm and the gates were shut precisely at 6 am and 6 pm. Anyone who was late not only could not work that day but lost an extra day's pay.

Memorials

- Richard Arkwright's barber shop in Churchgate, Bolton was demolished early in the 20th century. There is a small plaque above the door of the building that replaced it, recording Arkwright's occupancy.

- A Greater London Council blue plaque unveiled in 1984 commemorates Arkwright at 8 Adam Street in Charing Cross, London.[12]

- Sir Richard Arkwright lived at Rock House in Cromford, opposite his original mill. In 1788 he purchased an estate from Florence Nightingale's father, William, for £20,000 and set about building Willersley Castle for himself and his family. However just as the building was completed it was destroyed by fire, and Arkwright was forced to wait a further two years whilst it was rebuilt. He died aged 59 in 1792, never having lived in the castle, which was completed only after his death. Willersley Castle is now a hotel owned by the Christian Guild company.[13]

- In the UK, the Arkwright Scholarships Trust was set up in 1991 in Sir Richard's memory to provide prestigious scholarships to aspiring future leaders in engineering and technical design. By 2014, the Trust was awarding in the region of 400 scholarships annually to support students through their 'A' levels and Scottish Highers and to encourage students into university engineering courses or high-quality, higher-level apprenticeships.

References

- Notes

- ↑ Thirteen children were born but the others died in infancy

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20110612022208/http://www.lancashirepioneers.com/arkwright/parreg.jpg

- ↑ Smiles, Samuel (1866). Self Help. London.

- ↑ Musson, A. E.; Robinson, E. (June 1960). "The Origins of Engineering in Lancashire". The Journal of Economic History. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association. 20 (2): 209–233. JSTOR 2114855.

- ↑ "Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1792)".

- ↑ Gill, Gillian (24 October 2004). "'Nightingales'". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ Fitton, R. S. (1989), The Arkwrights: spinners of fortune, Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 57, ISBN 0-7190-2646-6, retrieved 2010-08-14

- ↑ Tann 1979, p. 248.

- 1 2 "Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1793)". BBC. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ Evans, Eric (1983). The Forging of the Modern State: Early Industrial Britain. Longman Group. p. 112. ISBN 0-582-48970-9.

- ↑ "Famous People of Derbyshire". Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "Richard Arkwright". Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "ARKWRIGHT, SIR RICHARD (1732–1792)". English Heritage. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- ↑ "Willersley Castle Hotel". Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- Bibliography

- Chapman, S. D. (1967), The early factory masters: the transition to the factory system in the midlands textile industry.

- Cooke, A. J. (1979), "Richard Arkwright and the Scottish cotton industry", Textile History, 10: 196–202, doi:10.1179/004049679793691394.

- Fitton, R. S. (1989), The Arkwrights: spinners of fortune, the major scholarly study.

- ——— & Wadsworth, A. P. (1958), The Strutts and the Arkwrights, 1758–1830: a study of the early factory system.

- Hewish, John (1987), "From Cromford to Chancery Lane: New Light on the Arkwright Patent Trials", Technology and Culture, 28 (1): 80–86, JSTOR 3105478.

- Hills, Richard L. (1970), "Sir Richard Arkwright and His Patent Granted in 1769", Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 24 (2): 254–260, doi:10.1098/rsnr.1970.0017, JSTOR 531292.

- Mason, J. J. (2004), "Arkwright, Sir Richard (1732–1792)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Tann, Jennifer (1973), "Richard Arkwright and technology", History, 58: 29–44, doi:10.1111/j.1468-229x.1973.tb02131.x.

- ——— (1970), The development of the factory.

- ——— (1979), "Arkwright's Employment of Steam Power", Business History, 21 (2): 247–250, doi:10.1080/00076797900000030, ISSN 0007-6791.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Arkwright. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Richard Arkwright |

Finlayson Henderson, Thomas (1885). "Arkwright, Richard (1732–1792)". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Finlayson Henderson, Thomas (1885). "Arkwright, Richard (1732–1792)". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.  "Arkwright, Sir Richard". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Arkwright, Sir Richard". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. "Arkwright, Richard". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Arkwright, Richard". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Richard Arkwright 1732–1792 Inventor of the Water Frame

- Richard Arkwright The Father of the Modern Factory System Biography and Legacy

- Essay on Arkwright

- Revolutionary Players website

- Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site

- The New Student's Reference Work/Arkwright, Sir Richard

- Descendants of Sir Richard Arkwright

- Richard Arkwright in Derbyshire

- Lancashire Pioneers – includes an obituary of Arkwright from 1792

- The Arkwright Scholarships Trust – named after Sir Richard. Awards prestigious Scholarships to aspiring future leaders in engineering and design in the UK.