Robert Shope

.jpg)

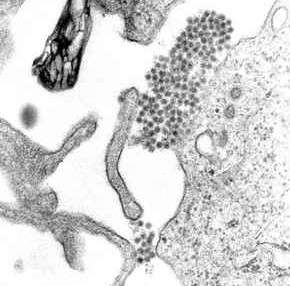

Robert Ellis Shope (February 21, 1929[1] – January 19, 2004) was an American virologist, epidemiologist and public health expert, particularly known for his work on arthropod-borne viruses and emerging infectious diseases. He discovered more novel viruses than any person previously, including members of the Arenavirus, Hantavirus, Lyssavirus and Orbivirus genera of RNA viruses. He researched significant human diseases, including dengue, Lassa fever, Rift Valley fever, yellow fever, viral hemorrhagic fevers and Lyme disease. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of viruses, and curated a global reference collection of over 5,000 viral strains. He was the lead author of a groundbreaking report on the threat posed by emerging infectious diseases, and also advised on climate change and bioterrorism.

Biography

Born in 1929 in Princeton, New Jersey, Shope was the son of Richard E. Shope, also a prominent virologist.[2][3] His brothers, Richard E. Shope, Jr and Thomas C. Shope, were also virologists.[4] Shope attended Cornell University, where he gained a BA in zoology (1951) and an MD (1954).[2][3][5] After an internship at Yale School of Medicine, Shope joined the U.S. Army Medical Corps and served for a total of three years at Camp Detrick in Frederick, Maryland and then at the U.S. Army Medical Research Unit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He subsequently joined the Rockefeller Foundation and – after a year studying with Max Theiler in New York – he was posted to Belém, Brazil, at the foundation's International Virus Program, where he spent six years, rising to direct the institute.[2][5][6]

Returning to the US in 1965, Shope joined the recently established Yale Arbovirus Research Unit (YARU) at Yale School of Medicine with other virologists from the Rockefeller Foundation. Initially an associate professor, he rose to direct the unit for 24 years.[2][5][6][7] Shope also headed the university's Division of Infectious Disease Epidemiology.[5] After his retirement from Yale in 1995, Shope and his colleague Robert B. Tesh moved to the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, where they founded a new arbovirus centre.[3][5][6][7][8] Shope subsequently held the university's John S. Dunn Distinguished Chair in Biodefense.[1][5]

Research

The virologist Charles H. Calisher described Shope as a "walking encyclopaedia on the arbovirus catalogue,"[1] and during his career Shope contributed to the discovery of hundreds of novel viruses[3][5] – more than any person previously.[2][9] His research encompassed not only the areas of virology, tropical and emerging infectious diseases, but also epidemiology, vector biology and public health.[2] Calisher and emerging infectious disease specialist C. J. Peters highlighted his multidisciplinary approach, stating that "He brought the virus community together and served as a bridge between classical arbovirology and many other disciplines" including ecology, genetics and structural biology.[10] Epidemiologist and emerging infectious disease specialist Stephen S. Morse considered Shope to exemplify the approach of "integrating the laboratory and the epidemiological and being able to think broadly about the evolutionary issues as well as the specifics."[1]

Shope initially studied the Australian disease then known as "epidemic polyarthritis" with S. G. Anderson, showing that it was caused by an alphavirus, later characterised as Ross River virus.[2] His interest in infectious diseases was stimulated by his military service in Malaysia, where he investigated fevers among army personnel and locals.[2][6] During his time in Brazil in the early 1960s, he characterised over fifty different arboviruses (viruses transmitted by arthropods) including Guama and Oropouche viruses, many previously unknown. He also studied the viruses' vertebrate reservoirs, including birds, marsupials and rodents.[2]

Later that decade while at YARU, he characterised novel arboviruses from birds in Egypt. In 1969, his research turned to outbreaks of Lassa and yellow fever in Nigeria. The following year, with Frederick A. Murphy, he discovered Duvenhage, Lagos bat and Mokola viruses, which were the first viruses shown to be related to rabies. He characterised Thottapalayam virus, later shown to be the first hantavirus, from an Indian shrew in 1971. With Murphy and others, he discovered multiple viruses related to bluetongue, including bluetongue 20 virus, the first bluetongue-like virus from Australia.[2] In the late 1970s, with Jim Meegan, he showed that Rift Valley fever virus – previously believed to be restricted to sub-Saharan Africa, and mainly to infect livestock – was the cause of an epidemic in Egypt in which around 200,000 people were infected.[2][11] With Allan Steer, he was the first to describe Lyme disease, a tick-borne bacterial disease, in the US. He subsequently worked on viral hemorrhagic fevers, discovering Sabiá and Guanarito viruses, the causative agents of Brazilian and Venezuelan hemorrhagic fevers.[2] He also researched dengue and its vaccines.[1][2]

During Shope's time at Yale, YARU became the global repository for arboviruses.[7][8] When he and Tesh moved to University of Texas Medical Branch in 1995, they brought the arbovirus collection – consisting of more than 4,000 strains of arbovirus and more than 1,000 other viral strains, as well as reagents such as antibodies – with them.[2][3][5][7][8] The collection is used by scientists internationally to identify virus strains.[7][8] At Galveston, Shope widened his focus to include bioterrorism, winning $3.7 million in funding to develop measures to counter the threat. His group identified alphavirus, arenavirus and flavivirus as potential bioterrorist risks, and Shope worked with structural biologist David Gorenstein to develop new small-molecule antivirals targeted against these viruses.[1][2][3][7]

Public health and advisory work

| “ | The medical community and society at large have tended to view acute infectious diseases as a problem of the past. But that assumption is wrong. We claimed victory too soon. | ” |

| — Robert Shope (1992), [1] | ||

Shope led a high-profile investigation, with Joshua Lederberg and Stanley Oaks, into the risks posed by emerging infectious diseases and the measures necessary to respond to them for the Institute of Medicine. The findings were published in 1992 as Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States, with Shope as the principal author, and the publication was swiftly recognised as groundbreaking. It suggested that the success of vaccines and antibiotics had led to the threat of infectious diseases being underestimated.[2][3][12][13] Shope stated at the press conference announcing the report's publication: "The medical community and society at large have tended to view acute infectious diseases as a problem of the past. But that assumption is wrong. We claimed victory too soon."[1] The report was important in improving the detection of infectious diseases in the US, and has been credited with stimulating renewed global interest in the area.[2][3][12][13] Shope continued to advise the US government on the topic later in the 1990s, and contributed to the establishment of American and international surveillance programs for infectious diseases including ProMED.[1]

Shope was one of seven scientists to brief Bill Clinton and Al Gore in 1997 on the effects of climate change, warning that the range of mosquitoes and other arthropod vectors would increase, affecting the prevalence of dengue, malaria and other infectious diseases.[2][3] He also served on the WHO Expert Panel on Virus Diseases and the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, as well as numerous committees and expert panels for US national bodies including the Institute of Medicine, National Institutes of Health and National Research Council.[2] He was one of the co-editors of Fields Virology, the "definitive" virology text.[2]

Personal life

Shope was married to Virginia; the couple had two sons and two daughters. He had idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, for which he received a lung transplant in December 2003. He died the following month in Galveston, from complications from the operation, at the age of 74.[2][3]

Societies, awards and honours

Shope served as president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) in 1980.[2][14] He was awarded the society's Bailey K. Ashford Medal (1974),[15] Richard M. Taylor Award (1987)[16] and Walter Reed Medal (1993).[17] In 2005, ASTMH established the Robert E. Shope International Fellowship in Infectious Diseases in his memory.[9] The University of Texas Medical Branch named its biosafety level 4 laboratory, completed just before his death, The Robert E. Shope, M.D. Laboratory, and also set up a fellowship in his memory.[2][18] A symposium was held in his honour on March 18–21, 2004.[10]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ivan Oransky (2004), "Robert E Shope" (PDF), The Lancet, 363: 1081, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15866-2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Frederick A. Murphy; Charles H. Calisher; Robert B. Tesh; David H. Walker (2004), "In Memoriam: Robert Ellis Shope: 1929–2004", Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10: 762–65, doi:10.3201/eid1004.040156, PMC 3323084

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Stuart Lavietes (January 23, 2004), "Robert Shope, 74, Virus Expert Who Warned of Epidemics", New York Times, retrieved January 29, 2016

- ↑ Obituaries, American Veterinary Medical Association, September 28, 2011, retrieved March 4, 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "In Memoriam: World Renowned Authority on Infectious Diseases, Robert E. Shope", YaleNews, Yale University, February 4, 2004, retrieved January 29, 2016

- 1 2 3 4 Robert B. Tesh (2004), "In Memoriam: Robert E. Shope, M.D.", Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 4: 91–94, doi:10.1089/1530366041210701

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin Enserink (2000), "Working in the Hot Zone: Galveston's Microbe Hunters", Science, 288: 598–600, doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.598, JSTOR 3075031, (subscription required (help))

- 1 2 3 4 Jocelyn Kaiser (1994), "Yale Arbovirus Team Heads South", Science, 266: 1470–71, doi:10.1126/science.7985009, JSTOR 2885158, (registration required (help))

- 1 2 Robert E. Shope: International Fellowship in Infectious Diseases: Application Guidelines (PDF), American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, retrieved January 29, 2016

- 1 2 C. J. Peters, Charles H. Calisher (2006), "Preface", Infectious Diseases from Nature: Mechanisms of Viral Emergence and Persistence, Springer, ISBN 3211299815

- ↑ Julie Ann Miller (1980), "African Epidemic: Where Is It Heading?", Science News, 117: 170–71, doi:10.2307/3964604, JSTOR 3964604, (subscription required (help))

- 1 2 Clarence J. Peters (2007), "Emerging Viral Diseases", in David M. Knipe, Peter M. Howley, Fields Virology, 1 (5 ed.), pp. 605–6, ISBN 0781760607

- 1 2 Felissa R. Lashley, Jerry D. Durham (2002), Emerging Infectious Diseases: Trends and Issues, Springer, pp. xi, ISBN 0826114741

- ↑ Membership Directory (PDF), American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, retrieved January 29, 2016

- ↑ Bailey K. Ashford Medal, American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, retrieved March 1, 2016

- ↑ American Committee on Arthropod-Borne Viruses (ACAV), American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, retrieved March 1, 2016

- ↑ Walter Reed Medal, American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, retrieved March 1, 2016

- ↑ Safety and Biocontainment: The Robert E. Shope, MD, Laboratory in the John Sealy Pavilion for Infectious Diseases Research, University of Texas Medical Branch, retrieved March 2, 2016