Palais Rohan, Strasbourg

| Palais Rohan | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Façade facing the River Ill | |

Location of Palais Rohan | |

| Alternative names | Palais des Rohan, Palais des Rohans |

| General information | |

| Type | Palace |

| Architectural style | Baroque |

| Location | Strasbourg, France |

| Address | 2, place du Château, 67000 Strasbourg |

| Coordinates | 48°34′51″N 7°45′08″E / 48.58083°N 7.75222°ECoordinates: 48°34′51″N 7°45′08″E / 48.58083°N 7.75222°E |

| Current tenants | Musée archéologique de Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, Musée des arts décoratifs de Strasbourg |

| Construction started | 1732 |

| Completed | 1742 |

| Owner | Municipality of Strasbourg |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Robert de Cotte, Joseph Massol |

The Palais Rohan (Rohan Palace) in Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, France is the former residence of the prince-bishops and cardinals of the House of Rohan, an ancient French noble family originally from Brittany, and is a major architectural, historical and cultural landmark in the city.[1] Built in the 1730s next to Strasbourg Cathedral according to designs provided by Robert de Cotte, it is considered a masterpiece[2][3] of French Baroque architecture and has hosted a number of illustrious guests since its completion in 1742.

Reflecting the history of Strasbourg and of France, the Palais was owned in turn by the nobility, the municipality, the monarchy, the State and the university. Its very architectural and iconographic conception, realised notably through the statues and reliefs of the façades, was intended to express the return of Catholicism to a city which had been dominated by Protestantism for the previous two centuries.[4]

Since the end of the 19th century the Palais has been home to three of Strasbourg's most important museums: the Archaeological Museum (Musée archéologique, basement), the Museum of Decorative Arts (Musée des arts décoratifs, ground floor) and the Museum of Fine Arts (Musée des beaux-arts, first and second floor). The municipal art gallery, Galerie Robert Heitz, in a lateral wing of the palace, is used for temporary exhibitions.

The Palais has been listed since 1920 as a Monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture.[5]

History

Up to 1871

The palace was commissioned by Cardinal Armand Gaston Maximilien de Rohan, Bishop of Strasbourg, from the architect Robert de Cotte, who provided initial plans in 1727.[6] In 1720, Cardinal de Rohan had already charged De Cotte with renovation and embellishment works on his castle in Saverne, the predecessor of the current Rohan Castle;[1] De Cotte had also previously designed the Hôtel du grand Doyenné, the first hôtel particulier in Louis Quinze style built in Strasbourg. The Palais Rohan in Strasbourg was built on the site of the former residence of the Bishop, the "Bishop's demesne" (German: Bischöflicher Fronhof, shortened to Bischofshof, "Bishop's court"),[7] which had been constructed from 1262 onwards.

Building work on the Palais Rohan, mostly in yellow sandstone with pink sandstone for the less visible parts, took place from 1732 until 1742[8] under the supervision of the municipal architect Joseph Massol, who also worked on the Hôtel de Hanau and the Hôtel de Klinglin during the early years of the project. Sculptures were provided, notably, by Robert Le Lorrain and Johann August Nahl, paintings by Pierre Ignace Parrocel and Robert de Séry.[9][N 1] A budget of 344,000 French livres had been established for the construction, but the final cost is estimated at one million French livres.[11]

The House of Rohan owned[N 2] the palace until the French Revolution, when it was confiscated, declared bien national ("State owned") and finally auctioned off.[13] Bought by the municipality in 1791, it became the new town hall the same year, succeeding the Neubau. Much of the furniture and many of the works of art in the Palais were sold and in 1793 the eight life-sized mural portraits of prince-bishops decorating the Salle des évêques (Bishops hall) were destroyed. They were replaced in 1796 by allegories of civic virtues painted by Joseph Melling. Only the portrait of Armand Gaston, the builder of the palace, was later restored to its original place with a 1982 copy after Hyacinthe Rigaud. Melling also replaced the overdoor portraits of kings of France decorating the same room with paintings of vases.[14][15] The Palais Rohan remained the hôtel de ville until 1805, when it was offered to Napoleon who, in return, gave the city the hitherto State-owned Hôtel de Hanau, an arrangement which proved favourable for everybody: for the municipality, the maintenance of the Hôtel de Hanau was less costly than that of the larger Palais Rohan; for Napoleon, the palace was the more conspicuous display of grandeur; for the Palace, imperial ownership meant renewed splendour. The gift to Napoleon was officially accepted by decree on 21 January 1806.[16] In the years before the Franco-Prussian War and the return of Alsace to Germany, the Palais Rohan was the property of the French State, which was in turn an Empire, a Kingdom, a Monarchy, a Republic, and an Empire again.

Since 1871

Between 1872 and 1884, before the opening of the Palais universitaire, the Palais Rohan was used as the central administrative building of the Kaiser-Wilhelms-Universität, the newly founded Imperial German version of the University of Strasbourg. Until the opening of the National and University Library in 1895, the Palais served as the university's library.[17] After this, the Palais, again the property of the city, was adapted to receive the municipal art collections which were being built up again after their total destruction during the Siege of Strasbourg. The first section of the new Kunstmuseum der Stadt Strassburg, established in 1898, was inaugurated in 1899. On August 11, 1944, the palace was damaged by British and American bombs.[18] Restoration measures were soon undertaken under the supervision of the architect Bertrand Monnet (1910–1989),[19] but in 1947, a fire broke out and devastated a significant part of the collections of the Musée des beaux-arts. This fire was an indirect consequence of the bombing raids: because of the destruction inflicted on the Palais, the building had suffered from damp, which was treated with welding torches, and poor handling of these caused the fire.[20] Rebuilding and refurbishing the palace took until well into the 1950s; the full restoration of the premises was completed in the 1990s.

Notable guests

King Louis XV of France stayed in the palace in 1744 (5 to 10 October), and Queen Marie Antoinette spent her first night on French soil there in 1770 (7 to 8 May). Maria Josepha of Saxony, Dauphine of France, spent two nights in the palace in 1747 (27 to 29 January). In 1805, 1806 and 1809, Emperor Napoleon stayed in the palace and had some of the furnishings changed to suit his tastes and those of his wife, Empress Josephine.[16][21][22] In 1810, Napoleon's second wife, Empress Marie Louise (born Austrian like Marie Antoinette) spent her first nights on French soil in the palace (22 to 25 March). Other royal French guests were Charles X in 1828 (7 and 8 September) and Louis Philippe I in 1831 (18 to 21 June).[13] Centuries later, before the 2009 Strasbourg–Kehl summit, the Palais Rohan hosted a meeting between French President Nicolas Sarkozy and American President Barack Obama as well as their wives Carla Bruni and Michelle Obama. The first great art exhibition in the palace after World War II, «L'Alsace française 1648–1848» was inaugurated on 13 June 1948 by Jean de Lattre de Tassigny.[23]

Structure

The palace, structured around a large and paved courtyard, has a trapezoidal plan and the land falls away toward the River Ill.[1] To compensate for the declivity, the riverside façade of the main wing has four floors (including the Mansard roof), while the courtyard façade has three floors. The half-buried floor corresponds to the basement and now houses the archaeological museum (see below, Museums). The riverside façade is thus both the highest and the widest of the Palace. The terrace before it is closed at both ends by elaborate wrought-iron gates adorned with the coat of arms of the House of Rohan. The symmetry impression of the riverside façade, arranged around an avant-corps of four columns with Corinthian capitals supporting a voluminous pediment again adorned with the coat of arms of the House of Rohan, is enlivened by the library wing on the west side, which offers a contrast in structure.[24] That wing was not part of the original 1727 plan but was conceived in 1733, after the cardinal bought up and demolished a row of houses on the current rue de Rohan. The architect, Robert de Cotte, was thus able to distribute the interior spaces on an even grander and also more practical plan.[25]

The courtyard façade of the main wing, in the same classical style as its counterpart facing the Ill,[1] is narrower. A strong emphasis is put on the verticality of the windows, by which means the impression of height is accentuated. Again, a central avant-corps is crowned with a pediment bearing reliefs and in this case also statues. Both façades are richly decorated with allegorical mascarons, to which the riverside façade adds a pair of broad wrought-iron balconies. Due to the difference in width and the trapezoidal plan, the centres of the façades are not aligned.[26]

The courtyard is divided in three sections separated by a row of arches. The left section (as seen from the cathedral) belongs to the Communs wing which housed the servants. The right section belongs to the stables wing. Left and right of the façade are exedras decorated with busts of Roman emperors. The entrance to the Palace is through the left exedra. Facing the courtyard façade is a peristyle with five arches. The central arch, the highest and widest, faces the centre of the façade and opens on the Palace's main gate.

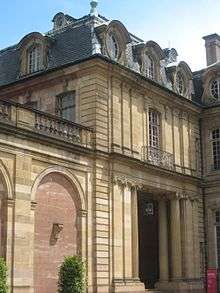

The front of the Palace on Place du Château (called Place de l'Évêché between 1740 and 1793),[27] in a more Baroque style than the rest of the Palace, is wide and curved. The central gate is framed by two pairs of columns and juts in the shape of a Triumphal arch. The upper part of the front section is crowned with statues representing allegories of faith and personifications of Christian virtues.[1] Plaster casts of some of these statues are displayed in the lapidarium inside the Barrage Vauban. The wooden portal (oak) and the walls left and right of the gate are decorated with trophies and heraldic symbols, while the two pavilions connecting the Communs and the stable wings with the gate section are decorated with mascarons representing Old Testament prophets and with crescent-shaped pediments, as opposed to the triangular pediments of the façades. The left pavilion housed the Palace's kitchens while the right pavilion housed the offices of the ecclesiastical court.[28]

Exterior views

The palace on 5 October 1744, during the visit of King Louis XV of France

The palace on 5 October 1744, during the visit of King Louis XV of France Aerial view from the Strasbourg Cathedral viewing platform

Aerial view from the Strasbourg Cathedral viewing platform- The main entrance

- Façade facing the inner courtyard

View from the main courtyard towards the entrance and the Cathedral

View from the main courtyard towards the entrance and the Cathedral Another view of the riverside façade

Another view of the riverside façade

Apartments

The apartments on the piano nobile today form a part of the Musée des arts décoratifs.[16]

The chambers of the prince-bishops and cardinals of the House of Rohan are divided into the grand appartement (display space, facing the river) and petit appartement (living space, facing the inner court), as in the Palace of Versailles. On either side of the suites are the two most spacious rooms of the palace, the Synod Hall (a single, very vast room composed of the dining hall and the guards' hall, separated by a row of arches) and the library, which both extend over the entire longitudinal axis of the wing. The library also serves as the nave of the palace's very small chapel. The grand appartement is composed of the Salle des évêques (Bishops' Hall) – the former Antichambre du roi –, the Chambre du roi (Bedchamber of the King), the Cabinet du roi (Cabinet of the King), also known as Salon d'assemblée (Assembly room) and the Garde-robe du roi (Cloakroom of the King). The "petit appartement" is composed of the Antichambre du prince-évêque, the Chambre du prince-évêque, the Cabinet du prince-évêque (turned into Napoleon's bedchamber after 1800) and the Garde-robe du prince-évêque. The castle's garderobe (Cabinet de commodités) are situated next to the Cloakroom of the prince-bishop.

In the wake of the French Revolution, many of the original furnishings had been sold. Some of the artworks, such as the original overdoors from the Salle des évêques, had become part of the municipal collections and were destroyed along with the museum situated in the Aubette when the Prussian Army shelled the city during the Siege of Strasbourg in 1870.[14] In the 20th century and especially during the reconstruction following the bomb damage of August 1944, a great deal of effort went into locating the surviving missing objects and replacing the lost artworks with identical or similar pieces.

Among the works of art on view in the apartments as they can now be seen, several stand out for their particular artistic and historic value. The set of eight (originally nine) tapestries depicting "The Story of Constantine" was woven around 1624 after modellos by Rubens. It had been commissioned by Louis XIII of France, who later presented it to the Marquis of Cinq-Mars.[29] Three tapestries are displayed in the Chambre du roi, one in the Cabinet du roi and four in the library. The set of eight 17th-century Italian busts of Roman emperors in the Salle des évêques belonged to the personal collection of Cardinal Mazarin. Both sets of works were bought in 1738 from the respective heirs by Armand Gaston de Rohan.[30] Another bust of particular value is the marble portrait of Armand Gaston, sculpted in 1730–1731 in Rome by Edmé Bouchardon.[31] It is also displayed in the library. The floor of the chapel is partly covered with an 1745 imitation of a Turkish carpet, woven in the Aubusson manufactory and bearing in its centre the coat of arms of Armand Gaston de Rohan.[21] Surviving works from Louis René de Rohan's vast collection of Japanese vases and Chinese pottery and lacquerware from the Ming and Qing dynasties, originally destined for the new castle in Saverne, are on display in most of the rooms.[32] A curio cabinet in the Garde-robe du prince-évêque displays dessert tableware from Sèvres, made in 1772−74 for Louis-René de Rohan's special embassy in Vienna, now belonging to the Musée des arts décoratifs.[33] A pair of large canvases with hunting dogs by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1742), now hanging in the Salle du synode, once hung in the Parisian hôtel particulier of Samuel-Jacques Bernard. The three paintings in the chapel are copies after Antonio da Correggio made in 1724 by Robert de Séry (1686–1733) on commission from Armand Gaston, whom he had met in Rome the same year.[34] De Séry would later provide many other paintings for the cardinal's apartments, all of them copies after greater masters. Napoleon's green bed is an original work by Jacob-Desmalter.[16]

The red canopy bed in the King's bedchamber is a 1989 copy of a bed on display in the Château d'Azay-le-Rideau, very similar to the lost original.[35] The portraits of kings Louis XIV and Louis XV of France in the library are copies made in 1950 after originals by Hyacinthe Rigaud kept in the Palace of Versailles. These 20th-century copies are replacements for the 18th-century copies of the same paintings that were destroyed during the French Revolution at the same time as the portraits of the prince-bishops in the Bishops' Hall (see above, History).[36] The overdoor paintings in the Antechamber of the prince-bishop are also 20th-century copies, replacing 18th-century copies after contemporary French masters such as Charles Le Brun that were destroyed in 1944.[37] The other paintings on the walls belong to the Musée des beaux-arts, such as La déification d’Énée ("The Deification of Aeneas", 1749) by Jean II Restout, on display in the Chambre du prince-évêque.

Interior views

.jpg) Synod hall

Synod hall Canopy bed in the King's bedchamber

Canopy bed in the King's bedchamber- Chinese ceramics in the King's bedchamber

- Tapestry from "The Story of Constantine" in the library

Bedchamber of Napoleon in the Empire style

Bedchamber of Napoleon in the Empire style 18th-century pedal harp in the Prince-bishop's bedchamber

18th-century pedal harp in the Prince-bishop's bedchamber 18th-century tiled stove in the Prince-bishop's antechamber

18th-century tiled stove in the Prince-bishop's antechamber Vases from China and a 17th-century bust of Septimius Severus from the Mazarin collection in the Bishop's hall

Vases from China and a 17th-century bust of Septimius Severus from the Mazarin collection in the Bishop's hall- Painting by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1742) in the Synod hall

- 1660s cabinet from Florence, Italy in the Prince-bishop's antechamber

Museums

Musée des Beaux-Arts

The Musée des Beaux-Arts (Museum of Fine Arts) on the first and second floors of the Palace is the successor of the Musée de peinture et de sculpture (Museum of painting and sculpture), established in 1803 and entirely destroyed by Prussian artillery shelling and the subsequent violent fire during the night of 24–25 August 1870. The new museum was opened in 1899. The collections as they can now be seen present an overview of European art from the 13th century to 1871, with considerable weight given to Italian as well as Flemish and Dutch paintings, with artists such as Hans Memling, Correggio, Anthony van Dyck, Giotto, Pieter de Hooch, Botticelli, Jacob Jordaens, Tintoretto, among many others. The collections of Upper Rhenish paintings and sculptures (Witz, Stoskopff, Baldung ...) had been moved into the dedicated Musée de l'Œuvre Notre-Dame in 1931.

Musée des arts décoratifs

The Musée des arts décoratifs (Museum of Decorative Arts) is located on the ground floor of the Palace. It was established in its current form in the years 1920–1924, when the collections of the Kunstgewerbe-Museum Hohenlohe (originally established in 1887 and located until then in the Renaissance former municipal slaughterhouse – the Grandes Boucheries or Große Metzig – which now hosts the Musée historique de Strasbourg[38]) were relocated in a wing adjacent to the Palace apartments. The collections suffered from the World War II bombing raids of 1944 but have been restored and replenished since. Besides the apartments of the prince-bishops and cardinals, the main focuses of the museum are the local productions of porcelain (Strasbourg faience), silver-gilt and clockmaking, with original parts of the medieval Strasbourg astronomical clock including the automaton rooster from 1354.[39] The reconstructed living room of a former hôtel particulier, the 1750s Hôtel Oesinger, displays 18th-century furniture in situ on a more intimate scale than the rooms of the Palace.[40]

Musée archéologique

The Musée archéologique (Archaeological Museum) is located in the basement of the Palace. The former archaeological collections of the city had been entirely destroyed along with the municipal library during the Siege of Strasbourg in 1870. A new collection was started in 1876 on behalf of the "Society for the preservation of the historical monuments of Alsace" (French: Société pour la conservation des Monuments historiques d'Alsace, German: Gesellschaft zur Erhaltung der geschichtlichen Denkmäler im Elsass). It was moved into the Palace in 1889, first opened to the public in 1896 and moved to its present location in 1907.[41] The museum displays finds from northern Alsace from the Paleolithic Era to the Merovingian dynasty, with a special focus on Argentoratum.

Literature

- Martin, Étienne; Walter, Marc: Le Palais Rohan; 2012, ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3

- Ludmann, Jean-Daniel; Livet, Georges: Le Palais Rohan de Strasbourg, 1979–1980 (two volumes), ISBN 978-2-7165-0026-5

- Ludmann, Jean-Daniel: Les grands appartements du Palais Rohan de Strasbourg, 1985

- Recht, Roland; Foessel, Georges; Klein, Jean-Pierre: Connaître Strasbourg, 1988, ISBN 2-7032-0185-0, pages 66–74

Footnotes

- ↑ Other, lesser known artists who worked on the building include the architects Laurent Gourlade and Étienne Le Chevalier, the sculptors Gaspard Pollet and Laurent Leprince, the ironworkers and locksmiths Jean-François Agon and his son Antoine Agon and the ébéniste Bernard Kocke.[10]

- ↑ The residence of the bishop belonged to the diocese, but due to the reforms Louis XIV forced on Alsace in 1687, the diocese became the property of selected French nobility. Thus Armand Gaston became landgrave of Lower Alsace and prince of the Holy Roman Empire as soon as he was created prince-bishop of Strasbourg.[1][12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Le Palais Rohan". musees.strasbourg.eu. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Johnson, Paul. "Columnists The message of a great European cathedral". pectator.co.uk. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Sherwood, Seth. "36 Hours in Strasbourg, France". nytimes.com. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Borda d'Água, Flávio. "Le Palais Rohan : un joyau princier au coeur de Strasbourg". Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ (French) French Ministry of Culture database entry.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 83. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ "Der Bischofshof zu Strassburg". Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 94. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. pp. 94; 116; 121; 153; 184. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. pp. 94; 95; 181. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ "Le pouvoir royal et l'architecture". crdp-strasbourg.fr. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- 1 2 Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 219. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- 1 2 Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 221 note 86. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Recht, Roland; Foessel, Georges; Klein, Jean-Pierre (1988). Connaître Strasbourg. p. 72. ISBN 2-7032-0185-0.

- 1 2 3 4 "Les appartements". musees.strasbourg.eu. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ↑ "La bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg" (PDF). mediadix.u-paris10.fr. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Bombardements de 1944". archi-wiki.org. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Bertrand Monnet". archi-wiki.org. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Peintures flamandes et hollandaises du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, Éditions des Musées de Strasbourg, February 2009, ISBN 978-2-35125-030-3 (French) – page 14

- 1 2 Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 190. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ "Kléber et Kellermann, enfants de Strasbourg.". napoleon1er.perso.neuf.fr. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Schnitzler, Bernadette (October 2009). Hans Haug, homme de musées : une passion à l'œuvre. Musées de la ville de Strasbourg. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-2-35125-071-6.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. pp. 87–90. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. pp. 51 and 83. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 83. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ "Historique du nom de la place". archi-wiki.org. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. pp. 58, 64. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 148. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 133. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 184. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Le goût chinois du cardinal de Rohan (French)

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 211. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 187. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 221, note 93. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 222, note 126. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ Martin, Étienne (2012). Le Palais Rohan. p. 193. ISBN 978-2-35125-098-3.

- ↑ "Musée historique - histoire". musees.strasbourg.eu. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Strasbourg - Cathedral area". travelforkids.com. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ "L'aile des arts décoratifs". musees.strasbourg.eu. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Schnitzler, Bernadette; Schneider, Malou (1985). Le Musée archéologique de Strasbourg. Strasbourg: Musées de Strasbourg. p. 11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palais Rohan, Strasbourg. |

- Palais Rohan, Strasbourg at the archINFORM database.

- Palais des Rohan - 2 place du Château on archi-wiki.org